better than some erroneous observations on certain fossils, which were supposed to show a plate at the oral pole between the five orals; but this plate, so far as it exists at all, is now known to be nothing but an oral shifted in position. The theory was that all the plates just described, and more particularly those of the cup, which were termed “the calycinal system,” could be traced, not merely in all crinoids, but in all Echinoderms, whether fixed forms such as cystids and blastoids, or free forms such as ophiuroids and echinoids, even—with the eye of faith—in holothurians. It was admitted that these elements might atrophy, or be displaced, or be otherwise obscured; but their complete and symmetrical disposition was regarded as typical and original. Thus the genera exhibiting it were regarded as primitive, and those orders and classes in which it was least obscured were supposed to approach most nearly the ancestral Echinoderm. Every one knows that an “apical system,” composed of two circlets known as “genitals” or basals and “oculars” or radials, occurs round the aboral pole of echinoids (fig. 3, A), and that a few genera (e.g. Salenia, fig. 3, B) possess a sub-central plate (the “suranal”), which might be identified with the centro-dorsal. It is also the case that many asterids (fig. 3, D) and ophiurids (fig. 3, C) have a similar arrangement of plates on the dorsal (i.e. aboral) surface of the disk. Accepting the homology of these apical systems with the calycinal system, the theory would regard the aboral pole of a sea-urchin or starfish as corresponding in everything, except its relations to the sea-floor, with the aboral pole of a fixed echinoderm.

The theory has been vigorously opposed, notably by Semon (op. cit.), who saw in the holothurians a nearer approach to the ancestral form than was furnished by any calyculate echinoderm, and by the Sarasins, who derived the echinoids from the holothurians through forms with flexible tests (Echinothuridae, which, however, are now known to be specialized in this respect). The support that appeared to be given to the theory by the presence of supposed calycinal plates in the embryo of echinoids and asteroids has been, in the opinion of many, undermined by E. W. MacBride (op. cit.), who has insisted that in the fixed stage of the developing starfish, Asterina, the relations of these plates to the stem are quite different from those which they bear in the developing and adult crinoid. But, however correct the observations and the homologies of MacBride may be, they do not, as Bury (op. cit.) has well pointed out, afford sufficient grounds for his inference that the abactinal (i.e. aboral) poles of starfish and crinoids are not comparable with one another, and that all conclusions based on the supposed homology of the dorso-central of echinoids and asteroids with that of crinoids are incorrect. Bury himself, however, has inflicted a severe blow on the theory by his proof that the so-called oculars of Echinoidea, which were supposed to represent the radials, are homologous with the “terminals” (i.e. the plates at the tips of the rays) in Asteroidea and Ophiuroidea, and therefore not homologous with the radially disposed plates often seen around the aboral pole of those animals. For, if these radial constituents of the supposed apical system in an ophiurid have really some other origin, why can we not say the same of the supposed basals? Indeed, Bury is constrained to admit that the view of Semon and others may be correct, and that these so-called calycinal systems may not be heirlooms from a calyculate ancestor, but may have been independently developed in the various classes owing to the action of similar causes. That this view must be correct is urged by students of fossils. Palaeontology lends no support to the idea that the dorso-central is a primitive element; it exists in none of the early echinoids, and the suranal of Saleniidae arises from the minor plates around the anus. There is no reason to suppose that the central apical plate of certain free-swimming crinoids has any more to do with the distal foot-plate of the larval Antedon stem than has the so-called centro-dorsal of Antedon itself, which is nothing but the compressed proximal end of the stem. As for the supposed basals of Echinoidea, Asteroidea and Ophiuroidea, they are scarcely to be distinguished among the ten or more small plates that surround the anus of Bothriocidaris, which is the oldest and probably the most ancestral of fossil sea-urchins (fig. 5). A calycinal system may be quite apparent in the later Ophiuroidea and in a few Asteroidea, but there is no trace of it in the older Palaeozoic types, unless we are to transfer the appellation to the terminals. Those plates are perhaps constant throughout sea-urchins and starfish (though it would puzzle any one to detect them in certain Silurian echinoids), and they may be traced in some of the fixed echinoderms; but there is no proof that they represent the radials of a simple crinoid, and there are certainly many cystids in which no such plates existed. Lovén and M. Neumayr adduced the Triassic sea-urchin Tiarechinus, in which the apical system forms half of the test, as an argument for the origin of Echinoidea from an ancestor in which the apical system was of great importance; but a genus appearing so late in time, in an isolated sea, under conditions that dwarfed the other echinoid dwellers therein, cannot seriously be thought to elucidate the origin of pre-Silurian Echinoidea, and the recent discovery of an intermediate form suggests that we have here nothing but degenerate descendants of a well-known Palaeozoic family (Lepidocentridae). But to pursue the tale of isolated instances would be wearisome. The calycinal theory is not merely an assertion of certain homologies, a few of which might be disputed without affecting the rest: it governs our whole conception of the echinoderms, because it implies their descent from a calyculate ancestor—not a “crinoid-phantom,” that bogey of the Sarasins, but a form with definite plates subject to a quinqueradiate arrangement, with which its internal organs must likewise have been correlated. To this ingenious and plausible theory the revelations of the rocks are more and more believed to be opposed.

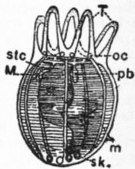

Pentactaea Theory.—In opposition to the calycinal theory has been the Pentactaea theory of R. Semon. There have always been many zoologists prepared to ascribe an ancestral character to the holothurians. The absence of an apical system of plates; the fact that radial symmetry has not affected the generative organs, as it has in all other recent classes; the well-developed muscles of the body-wall, supposed to be directly inherited from some worm-like ancestor; the presence on the inner walls of the body in the family Synaptidae of ciliated funnels, which have been rashly compared to the excretory organs (nephridia) of many worms; the outgrowth from the rectum in other genera of caeca (Cuvierian organs and respiratory trees), which recall the anal glands of the Gephyrean worms; the absence of podia (tube-feet) in many genera, and even of the radial water-vessels in Synaptidae; the absence of that peculiar structure known in other echinoderms by the names “axial organ,” “ovoid gland,” &c.; the simpler form of the larva—all these features have, for good reason or bad, been regarded as primitive. Some of the more striking of these features are confined to Synaptidae; in that family too the absence of the radial water-vessels from the adult is correlated with continuity of the circular muscle-layer, while the gut runs almost straight from the anterior mouth to the posterior anus. Early in the life-history of Synapta occurs a stage with five tentacles around the mouth, and into these pass canals from the water-ring, the radial canals to the body-wall making a subsequent, and only temporary, appearance (fig. 4). Semon called this stage the Pentactula, and supposed that, in its early history, the class had passed through a similar stage, which he called the Pentactaea, and regarded as the ancestor of all Echinoderms. It has since been proved that the five tentacles with their canals are interradial, so that one can scarcely look on the Pentactula as a primitive stage, while the apparent simplicity of the Synaptidae, at least as compared with other holothurians, is now believed to be the result of regressive