from the Persian tambal, whence is derived the modern French timbales; nacaire, naquaire or nakeres (English spelling), from the Arabic nakkarah or noqqārich (Bengali, nāgarā), and the German Pauke, M.H.G. Bûke or Pûke, which is probably derived from byk, the Assyrian name of the instrument.

|

|

| (Geo. Potter & Co. of Aldershot.) |

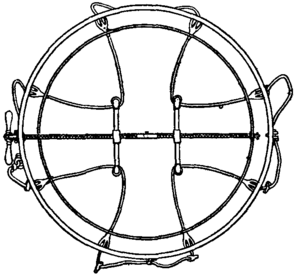

Fig. 1.—Mechanical Kettledrum, showing the system of cords inside the head. |

A line in the chronicles of Joinville definitely establishes the

identity of the nakeres as a kind of drum: “Lor il fist sonner

les labours que l'on appelle nacaires.” The nacaire is among

the instruments mentioned by Froissart as having been used

on the occasion of Edward III.’s triumphal entry into Calais

in 1347: “trompes, tambours, nacaires, chalemies, muses.”[1]

Chaucer mentions them in the description of the tournament

in the Knight’s Tale (line 2514):—

| “ | Pipes, trompes, nakeres and clarionnes That in the bataille blowen blody sonnes.” |

The earliest European illustration showing kettledrums is the

scene depicting Pharaoh’s banquet in the fine illuminated MS.

book of Genesis of the 5th or 6th century, preserved in Vienna.

There are two pairs of shallow metal bowls on a table, on which

a woman is performing with two sticks, as an accompaniment

to the double pipes.[2] As a companion illumination may be

cited the picture of an Eastern banquet given in a 14th century

MS. at the British Museum (Add. MS. 27,695), illuminated by a

skilled Genoese. The potentate is enjoying the music of various

instruments, among which are two kettledrums strapped to the

back of a Nubian slave. This was the earlier manner of using

the instrument before it became inseparably associated with the

trumpet, sharing its position as the service instrument of the

cavalry. Jost Amman[3] gives a picture of a pair of kettledrums

with banners being played by an armed knight on horseback.

|

| (From Hartel u. Wickhoff’s “Die Wiener Genesis,” Jahrbuch der kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses.) |

Fig. 2.—Kettledrums in an early Christian MS. |

|

Fig. 3.—Medieval Kettledrums, 14th century. (Brit. Museum.) |

As in the case of the trumpet, the use of the kettledrum was

placed under great restrictions in Germany and France and

to some extent in England, but it was used in churches with

the trumpet.[4] No French or German regiment was allowed

kettledrums unless they had been captured from the enemy,

and the timbalier or the Heerpauker on parade, in reviews

and marches generally, rode at the head of the squadron; in

battle his position was in the wings. In England, before the

Restoration, only the Guards were allowed kettledrums, but

after the accession of James II. every regiment of horse was

provided with them.[5] Before the Royal Regiment of Artillery

was established, the master-general of ordnance was responsible for the raising of trains of artillery. Among his retinue in time of war were a trumpeter and kettledrummer. The kettledrums were mounted on a chariot drawn by six white horses. They appeared in the field for the first time in a train of artillery during the Irish rebellion of 1689, and the charges for ordnance

- ↑ Panthéon littéraire (Paris, 1837), J. A. Buchon, vol. i. cap. 322, p. 273.

- ↑ Reproduced by Franz Wickhoff, “Die Wiener Genesis,” supplement to the 15th and 16th volumes of the Jahrb. d. kunsthistorischen Sammlungen d. allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses (Vienna, 1895); see frontispiece in colours and plate illustration XXXIV.

- ↑ Artliche u. kunstreiche Figuren zu der Reutierey (Frankfort-on-Main, 1584).

- ↑ See Michael Praetorius, Syntagma Musicum and Monatshefte f. Musikgeschichte, Jahrgang x. 51.

- ↑ See Georges Kastner, op. cit., pp. 10 and 11; Johann Ernst Altenburg, Versuch einer Anleitung z. heroisch-musikalischen Trompeter u. Paukerkunst (Halle, 1795), p. 128; and H. G. Farmer, Memoirs of the Royal Artillery Band, p. 23, note 1 (London, 1904).