rejection had been at one time imminent; but Massachusetts became a strong Federalist state. Indeed, the general interest of her history in the quarter-century after the adoption of the Constitution lies mainly in her connexion with the fortunes of that great political party. Her leading politicians were out of sympathy with the conduct of national affairs (in the conduct of foreign relations, the distribution of political patronage, naval policy, the question of public debt) from 1804—when Jefferson’s party showed its complete supremacy—onward; and particularly after the passage of the Embargo Act of 1807, which caused great losses to Massachusetts commerce, and, so far from being accepted by her leaders as a proper diplomatic weapon, seemed to them designed in the interests of the Democratic party. The Federalist preference for England over France was strong in Massachusetts, and her sentiment was against the war with England of 1812–15. New England’s discontent culminated in the Hartford Convention (Dec. 1814), in which Massachusetts men predominated. The state, however, bore her full part in the war, and much of its naval success was due to her sailors.

During the interval till the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Massachusetts held a distinguished place in national life and politics. As a state she may justly be said to have been foremost in the struggle against slavery.[1] She opposed the policy that led to the Mexican War in 1846, although a regiment was raised in Massachusetts by the personal exertions of Caleb Cushing. The leaders of the ultra non-political abolitionists (who opposed the formation of the Liberty party) were mainly Massachusetts men, notably W. L. Garrison and Wendell Phillips. The Federalist domination had been succeeded by Whig rule in the state; but after the death of the great Whig, Daniel Webster, in 1852, all parties disintegrated, re-aligning themselves gradually in an aggressive anti-slavery party and the temporizing Democratic party. First, for many years the Free-Soilers gained strength; then in 1855 in an extraordinary party upheaval the Know-Nothings quite broke up Democratic, Free-Soil and Whig organizations; the Free-Soilers however captured the Know-Nothing organization and directed it to their own ends; and by their junction with the anti-slavery Whigs there was formed the Republican party. To this the original Free-Soilers contributed as leaders Charles Sumner and C. F. Adams; the Know-Nothings, Henry Wilson and N. P. Banks; and later, the War Democrats, B. F. Butler—all men of mark in the history of the state. Charles Sumner, the most eminent exponent of the new party, was the state’s senator in Congress (1851–1874). The feelings which grew up, and the movements that were fostered till they rendered the Civil War inevitable, received something of the same impulse from Massachusetts which she had given a century before to the feelings and movements forerunning the War of American Independence. When the war broke out it was her troops who first received hostile fire in Baltimore, and turning their mechanical training to account opened the obstructed railroad to Washington. In the war thus begun she built, equipped and manned many vessels for the Federal navy, and furnished from 1861 to 1865 26,163 (or, including final credits, probably more than 30,000) men for the navy. During the war all but twelve small townships raised troops in excess of every call, the excess throughout the state amounting in all to more than 15,000 men; while the total recruits to the Federal army (including re-enlistments) numbered, according to the adjutant-general of the state, 159,165 men, of which less than 7000 were raised by draft.[2] The state, as such, and the townships spent $42,605,517.19 in the war; and private contributions of citizens are reckoned in addition at about $9,000,000, exclusive of the aid to families of soldiers, paid then and later by the state.

Since the close of the war Massachusetts has remained generally steadfast in adherence to the principles of the Republican party, and has continued to develop its resources. Navigation, which was formerly the distinctive feature of its business prosperity, has under the pressure of laws and circumstances given place to manufactures, and the development of carrying facilities on the land rather than on the sea.

In the Spanish-American War of 1898 Massachusetts furnished 11,780 soldiers and sailors, though her quota was but 7388; supplementing from her own treasury the pay accorded them by the national government.

No statement of the influence which Massachusetts has exerted upon the American people, through intellectual activity, and even through vagary, is complete without an enumeration of the names which, to Americans at least, are the signs of this influence and activity. In science the state can boast of John Winthrop, the most eminent of colonial scientists; Benjamin Thompson (Count Rumford); Nathaniel Bowditch, the translator of Laplace; Benjamin Peirce and Morse the electrician; not to include an adopted citizen in Louis Agassiz. In history, Winthrop and Bradford laid the foundations of her story in the very beginning; but the best example of the colonial period is Thomas Hutchinson, and in later days Bancroft, Sparks, Palfrey, Prescott, Motley and Parkman. In poetry, a pioneer of the modern spirit in American verse was Richard Henry Dana; and later came Bryant, Longfellow, Whittier, Lowell and Holmes. In philosophy and the science of living, Jonathan Edwards, Franklin, Channing, Emerson and Theodore Parker. In education, Horace Mann; in philanthropy, S. G. Howe. In oratory, James Otis, Fisher Ames, Josiah Quincy, junr., Webster, Choate, Everett, Sumner, Winthrop and Wendell Phillips; and, in addition, in statesmanship, Samuel Adams, John Adams and John Quincy Adams. In fiction, Hawthorne and Mrs Stowe. In law, Story, Parsons and Shaw. In scholarship, Ticknor, William M. Hunt, Horatio Greenough, W. W. Story and Thomas Ball. The “transcendental movement,” which sprang out of German affiliations and produced as one of its results the well-known community of Brook Farm (1841–1847), under the leadership of Dr George Ripley, was a Massachusetts growth, and in passing away it left, instead of traces of an organization, a sentiment and an aspiration for higher thinking which gave Emerson his following. When Massachusetts was called upon to select for Statuary Hall in the capitol at Washington two figures from the long line of her worthies, she chose as her fittest representatives John Winthrop, the type of Puritanism and state-builder, and Samuel Adams (though here the choice was difficult between Samuel Adams and John Adams) as her greatest leader in the heroic period of the War of Independence.

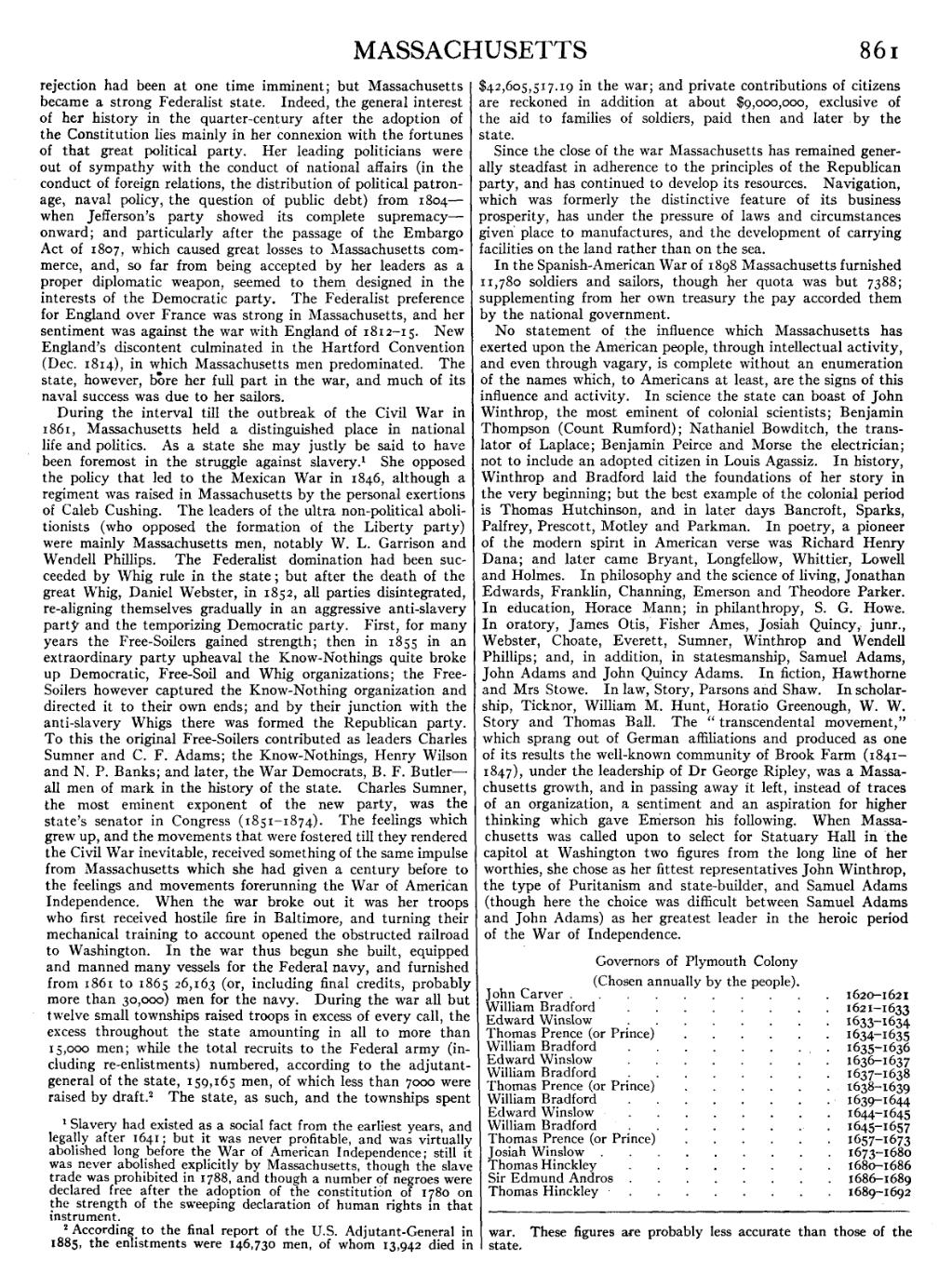

| Governors of Plymouth Colony

(Chosen annually by the people). | ||

| John Carver | 1620–1621 | |

| William Bradford | 1621–1633 | |

| Edward Winslow | 1633–1634 | |

| Thomas Prence (or Prince) | 1634–1635 | |

| William Bradford | 1635–1636 | |

| Edward Winslow | 1636–1637 | |

| William Bradford | 1637–1638 | |

| Thomas Prence (or Prince) | 1638–1639 | |

| William Bradford | 1639–1644 | |

| Edward Winslow | 1644–1645 | |

| William Bradford | 1645–1657 | |

| Thomas Prence (or Prince) | 1657–1673 | |

| Josiah Winslow | 1673–1680 | |

| Thomas Hinckley | 1680–1686 | |

| Sir Edmund Andros | 1686–1689 | |

| Thomas Hinckley | 1689–1692 | |

- ↑ Slavery had existed as a social fact from the earliest years, and legally after 1641; but it was never profitable, and was virtually abolished long before the War of American Independence; still it was never abolished explicitly by Massachusetts, though the slave trade was prohibited in 1788, and though a number of negroes were declared free after the adoption of the constitution of 1780 on the strength of the sweeping declaration of human rights in that instrument.

- ↑ According to the final report of the U.S. Adjutant-General in 1885, the enlistments were 146,730 men, of whom 13,942 died in war. These figures are probably less accurate than those of the state.