with an engine of this type it was found possible to work it on an expenditure of 13 ℔ of water per brake-horse-power hour.

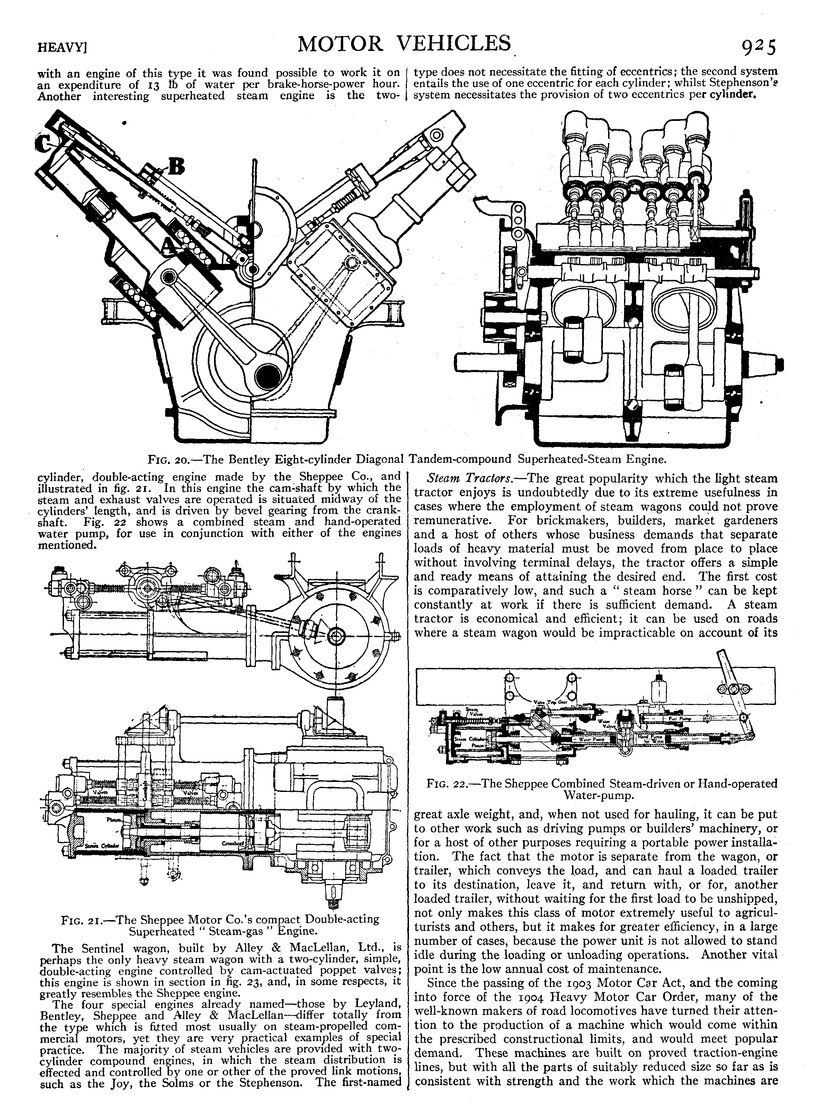

Fig. 20.—The Bentley Eight-cylinder Diagonal Tandem-compound Superheated-Steam Engine.

Another interesting superheated steam engine is the two-cylinder, double-acting engine made by the Sheppee Co., and illustrated in fig. 21. In this engine the cam-shaft by which the steam and exhaust valves are operated is situated midway of the cylinders’ length, and is driven by bevel gearing from the crank-shaft. Fig. 22 shows a combined steam and hand-operated water pump, for use in conjunction with either of the engines mentioned.

Fig. 21.—The Sheppee Motor Co.’s compact Double-acting

Superheated “Steam-gas” Engine.

The Sentinel wagon, built by Alley & MacLellan, Ltd., is perhaps the only heavy steam wagon with a two-cylinder, simple, double-acting engine controlled by cam-actuated poppet valves; this engine is shown in section in fig. 23, and, in some respects, it greatly resembles the Sheppee engine.

The four special engines already named—those by Leyland, Bentley, Sheppee and Alley & MacLellan—differ totally from the type which is fitted most usually on steam-propelled commercial motors, yet they are very practical examples of special practice. The majority of steam vehicles are provided with two-cylinder compound engines, in which the steam distribution is effected and controlled by one or other of the proved link motions, such as the joy, the Solms or the Stephenson. The first-named type does not necessitate the fitting of eccentrics; the second system entails the use of one eccentric for each cylinder; whilst Stephenson’s system necessitates the provision of two eccentrics per cylinder.

Fig. 22.—The Sheppee Combined Steam-driven or Hand-operated Water-pump.

Steam Tractors.—The great popularity which the light steam tractor enjoys is undoubtedly due to its extreme usefulness in cases where the employment of steam wagons could not prove remunerative. For brickmakers, builders, market gardeners and a host of others whose business demands that separate loads of heavy material must be moved from place to place without involving terminal delays, the tractor offers a simple and ready means of attaining the desired end. The first cost is comparatively low, and such a “steam horse” can be kept constantly at work if there is sufficient demand. A steam tractor is economical and efficient; it can be used on roads where a steam wagon would be impracticable on account of its great axle weight, and, when not used for hauling, it can be put to other work such as driving pumps or builders’ machinery, or for a host of other purposes requiring a portable power installation. The fact that the motor is separate from the wagon, or trailer, which conveys the load, and can haul a loaded trailer to its destination, leave it, and return with, or for, another loaded trailer, without waiting for the first load to be unshipped, not only makes this class of motor extremely useful to agriculturists and others, but it makes for greater efficiency, in a large number of cases, because the power unit is not allowed to stand idle during the loading or unloading operations. Another vital point is the low annual cost of maintenance.

Since the passing of the 1903 Motor Car Act, and the coming into force of the 1904 Heavy Motor Car Order, many of the well-known makers of road locomotives have turned their attention to the production of a machine which would come within the prescribed constructional limits, and would meet popular demand. These machines are built on proved traction-engine lines, but with all the parts of suitably reduced size so far as is consistent with strength and the work which the machines are