called upon to perform. The locomotive type of boiler, with

large fire-box, a heating surface of about 65 sq. ft., and a grate

area of some 3 sq. ft., is used by the leading makers.

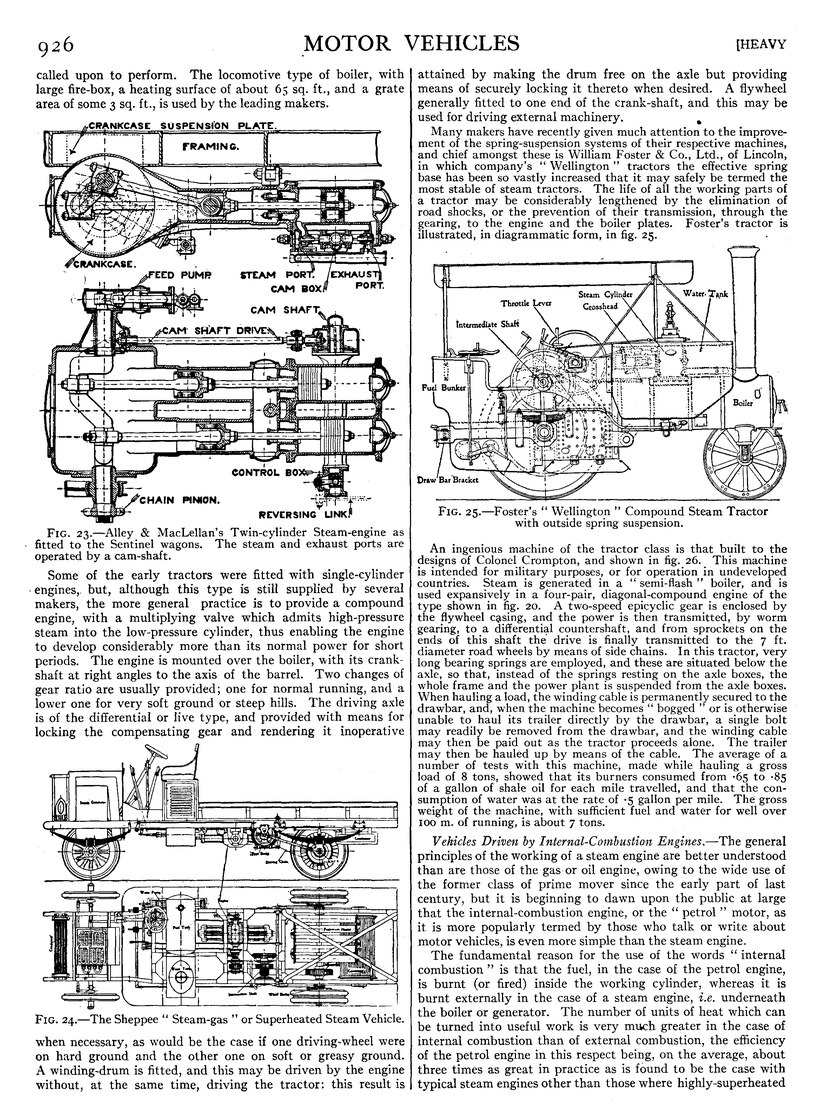

Fig. 23.—Alley & MacLellan’s Twin-cylinder Steam-engine as fitted to the

Sentinel wagons. The steam and exhaust ports are operated by a cam-shaft.

Some of the early tractors were fitted with single-cylinder engines, but, although this type is still supplied by several makers, the more general practice is to provide a compound engine, with a multiplying valve which admits high-pressure steam into the low-pressure cylinder, thus enabling the engine to develop considerably more than its normal power for short periods. The engine is mounted over the boiler, with its crank-shaft at right angles to the axis of the barrel. Two changes of gear ratio are usually provided; one for normal running, and a lower one for very soft ground or steep hills. The driving axle is of the differential or live type, and provided with means for locking the compensating gear and rendering it inoperative

Fig. 24.—The Sheppee “Steam-gas” or Superheated Steam Vehicle.

when necessary, as would be the case if one driving-wheel were on hard ground and the other one on soft or greasy ground. A winding-drum is fitted, and this may be driven by the engine without, at the same time, driving the tractor: this result is, attained by making the drum free on the axle but providing means of securely locking it thereto when desired. A flywheel generally fitted to one end of the crank-shaft, and this may be used for driving external machinery.

Many makers have recently given much attention to the improvement of the spring-suspension systems of their respective machines, and chief amongst these is William Foster & Co., Ltd., of Lincoln, in which company’s “Wellington” tractors the effective spring base has been so vastly increased that it may safely be termed the most stable of steam tractors. The life of all the working parts of a tractor may be considerably lengthened by the elimination of road shocks, or the prevention of their transmission, through the gearing, to the engine and the boiler plates. Foster’s tractor is illustrated, in diagrammatic form, in fig. 25.

Fig. 25.—Foster’s “Wellington” Compound Steam Tractor with outside spring suspension.

An ingenious machine of the tractor class is that built to the designs of Colonel Crompton, and shown in fig. 26. This machine is intended for military purposes, or for operation in undeveloped countries. Steam is generated in a “semi-flash” boiler, and is used expansively in a four-pair, diagonal-compound engine of the type shown in fig. 20. A two-speed epicyclic gear is enclosed by the flywheel casing, and the power is then transmitted, by Worm gearing, to a differential countershaft, and from sprockets on the ends of this shaft the drive is finally transmitted to the 7 ft. diameter road wheels by means of side chains. In this tractor, very long bearing springs are employed, and these are situated below the axle, so that, instead of the springs resting on the axle boxes, the whole frame and the power plant is suspended from the axle boxes. When hauling a load, the winding cable is permanently secured to the drawbar, and, when the machine becomes “bogged” or is otherwise unable to haul its trailer directly by the drawbar, a single bolt may readily be removed from the drawbar, and the winding cable may then be paid out as the tractor proceeds alone. The trailer may then be hauled up by means of the cable. The average of a number of tests with this machine, made while hauling a gross load of 8 tons, showed that its burners consumed from ·65 to ·85 of a gallon of shale oil for each mile travelled, and that the consumption of water was at the rate of ·5 gallon per mile. The gross weight of the machine, with sufficient fuel and water for well over 100 m. of running, is about 7 tons.

Vehicles Driven by Internal-Combustion Engines.—The general principles of the Working of a steam engine are better understood than are those of the gas or oil engine, owing to the wide use of the former class of prime mover since the early part of last century, but it is beginning to dawn upon the public at large that the internal-combustion engine, or the “petrol” motor, as it is more popularly termed by those who talk or write about motor vehicles, is even more simple than the steam engine.

The fundamental reason for the use of the words “internal combustion” is that the fuel, in the case of the petrol engine, is burnt (or fired) inside the working cylinder, whereas it is burnt externally in the case of a steam engine, i.e. underneath the boiler or generator. The number of units of heat which can be turned into useful work is very much greater in the case of internal combustion than of external combustion, the efficiency of the petrol engine in this respect being, on the average, about three times as great in practice as is found to be the case with typical steam engines other than those where highly-superheated