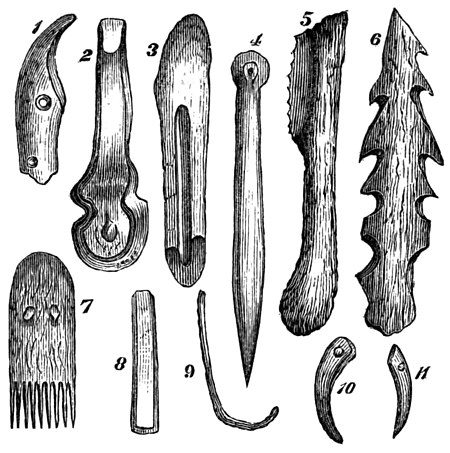

prevent their falling into the water. Hippocrates records that the colonists of the Phasis lived in reed huts in the middle of the river. Certain Assyrian bass reliefs represent inhabited artificial islands formed of woven rushes. Venezuela received its name (little Venice) from the Spanish discoverers because of the houses built on piles in the lagoon of Maracaibo. The lake dwellings of extinct peoples represent all stages of civilization from the age of stone to the dawn of the iron age. Those of Lake Moosseedorf, Switzerland, are supposed to be the oldest, and those of Ireland the most recent.—In 1829 an excavation on the shore of Lake Zürich at Obermeilen revealed the existence of ancient piles and other antiquities, but no extended examination was made. The winter of 1853–'4 in Switzerland was one of extraordinary drought and cold; the rivers shrank to their smallest dimensions, and the level of the lakes was lower than had ever before been known. The inhabitants on the shore of a little bay between Obermeilen and Dallikon took advantage of the low water to extend their gardens by building a wall and filling the space back of it with mud dredged from in front. The dredging brought to light the heads of a system of piles, great quantities of stags' horns, and several ancient implements. Dr. Ferdinard Keller followed up this discovery, and similar remains of prehistoric villages were found in Lakes Zürich, Constance, Geneva, Bienne, Neufchâtel, Morat, and several of the smaller lakes of Switzerland. From 20 to 50 settlements have been explored in each of the larger lakes; and immense numbers of implements of horn, bone, stone, bronze, and pottery have been found, with a few of gold, wood, and iron, mingled with bones of animals, and in a very few cases human remains. The most perfect example of a lake dwelling of the stone age was in the little lake of Moosseedorf, near Bern. The water was artificially lowered 8 ft. in the winter of 1855–'6, which revealed a settlement at each extremity of the lake; the one at the eastern end was most thoroughly examined. The piles had been driven irregularly, the mass forming a parallelogram 55 by 70 ft. They were stems of oak, birch, fir, and aspen, from 5 to 7 in. in diameter, some being split and some still retaining the bark. The remains of a bridge which had connected the settlement with the shore were found. The superstructure had apparently been destroyed by fire, only portions of the charred wood remaining. The implements were found, not in the mud of the ancient lake bottom, but in a stratum next above it, now called the relic bed, consisting of loose peat, gravel, clay, wood, and charcoal, from 5 in. to 2 ft. thick. Many of the heaviest implements were near the top of the bed, and many of the lightest near the bottom. Among them were a harpoon of stag's horn, a flint saw fastened with asphalt in a handle of fir wood, needles made of boars' teeth, awls, knives, pincers, chisels, and arrow heads of bone, fish hooks of boar's tusk, and a comb of yew wood. There were also numerous bones of animals, some of which bore the marks of stone axes and saws; a few fragments of pottery, some incrusted with soot; linseed, and burnt wheat and barley.

Every hillock in the marsh land around this settlement is full of chips and flakes and unfinished instruments of flint. The lake dwellings situated in what are now peat moors offer in some respects a better opportunity for investigation than those which are still under water. The best specimen of this kind was discovered in 1858 at Robenhausen near Lake Pfäffikon, in the canton of Zürich. The space covered with piles is an irregular quadrangle containing nearly three acres, which must have been about 2,000 paces from the ancient western shore of the lake in which it stood, and about 3,000 from the eastern; the piles of a bridge connecting it with the latter still remain. The piles of this village, numbering about 100,000, were of oak, beech, and fir, some of them being split, were 10 or 11 ft. long, sharpened with stone hatchets, and driven in from 2 to 3 ft. apart. The platform was made of cross timbers and boards, fastened to the piles with wooden pins. The outermost piles were bound together with hurdle work. Investigation revealed three systems of piles, one above the other, indicating different periods of habitation. The piles of the two lower systems are round stems of soft wood, those of the uppermost split trunks of oak. Here were found mealing stones, hearth stones, wheat and barley, 8 lbs. of bread, burnt apples and pears, beech nuts, acorns, cherry stones, flax, cords, nets, mats, and woven cloth of bast and of flax, an abundance of broken pottery, many