Panama, past and present/Chapter 10

CHAPTER X

HOW THE FRENCH TRIED TO DIG THE CANAL

THERE is a large, iron steam-launch, used by our government to carry sick canal-workers to the sanatorium on Taboga Island, that was brought to the Isthmus by the French, but for a very different purpose. With two oceans to float it in, they stuck this launch high and dry at the bottom of the unfinished Gaillard Cut, to the great astonishment of the Americans who found it there in 1904. It had been placed there, explained an old employee of the French company, and a trench dug round it, so that when the floods of the rainy season filled the trench, a clever photographer could take a picture showing "navigation through the Cut." Such a picture, when exhibited in Paris, would make people think the work was nearly finished, and that the money they had invested in it was well spent. It is a good illustration of how the French tried to dig the Canal.

From the beginning, the French Canal Company (known in full as "La Société International du Canal Interoceanique") sailed a great many boats on dry land and made people believe they were afloat. They sent Lieutenant Lucien Napoleon Bonaparte Wyse of the French Navy, to make a survey of the Isthmus in 1877, and, though he never went more than two-thirds of the distance from Panama to Colon, he brought back complete plans, with the cost of construction figured out to within ten per cent, for a sea-level canal between the two cities. After a little more work on the Isthmus, next year, Wyse obtained a concession from the government

COLOMBIA NATIONAL FLAG.

at Bogotá, granting the exclusive right to build an interoceanic canal, not only at Panama, but anywhere else through the territory of the United States of Colombia, as New Granada was then called. When we remember the thorough preliminary surveys made for the Panama Railroad by Stephens and Hughes and Baldwin, it seems incredible that the French people should have taken Wyse seriously, and invested hundreds of millions of dollars in an enterprise of which they knew so little. What blinded them was the name of the man who now came forward as the head of that enterprise, Ferdinand de Lesseps.

He was "the great Frenchman," the most popular and honored man in France, because of the glory he had won her by the construction of the Suez Canal. Sent on a diplomatic mission to Egypt, de Lesseps, though not a trained engineer, had recognized the ease with which a ship canal could be cut through the hundred miles of level sand that separated the Mediterranean from the Red Sea. It took both imagination and courage to conceive a ship canal of that length, and the greatest difficulty, as with every new thing, lay in persuading people that it would not necessarily be a failure, because there had never been anything just like it before. The actual digging was as simple as making the moat round a sand castle at the seashore. A company was formed in France, the Khedive of Egypt took a majority of the stock, and forced thousands of his subjects to work as laborers for virtually nothing. The Suez Canal was completed in ten years, at a cost of a million dollars a mile, and ever since its opening in 1869 it has paid its owners handsome profits. But the bankrupt successor of the Khedive sold his stock to the British government, which has a very great interest in Suez because its ships must pass through there on the way to India, and to-day the English are the real rulers both of Egypt and the Suez Canal.

De Lesseps first appeared in connection with Panama as chairman of the International Canal Congress held in Paris in May, 1879. The experienced naval officers and trained engineers who were invited from many different countries, found themselves in a helpless minority. Their advice was not asked, and their presence had been sought merely to lend dignity and a show of authority to M. de Lesseps's decision, already made, to build a sea-level canal across the Isthmus of Panama according to the plans of Lieutenant Wyse. The chairman allowed no discussion of the advantages either of a lock canal at Panama, or of any kind of a canal at Nicaragua, but forced the adoption of the type and route he favored, by the vote of a small majority of French admirers, very few of whom were practical engineers. Then, adjourning his dummy congress, de Lesseps came forward as head of the French Canal Company, which had already paid Lieutenant Wyse $2,000,000 for his worthless surveys and valuable concessions. Finally, after everything had been decided on, de Lesseps went to the Isthmus with an imposing "Technical Commission" of distinguished engineers.

When President Roosevelt made his first inspection of the Panama Canal, nearly twenty-seven years afterwards, he went there in November, at the climax of the rainy season, because he wanted to see things at their worst. For exactly the opposite reason, de Lesseps chose December and January, when the rains have virtually ceased, and the country looks its prettiest. After one trip across the Panama Railroad, many speeches, and no end of feasting and drinking of healths, he hurried away to the United States, where he spent a great deal more time trying to induce the Americans to invest money in his enterprise, but without much success. De Lesseps made another trip to the Isthmus in 1886.

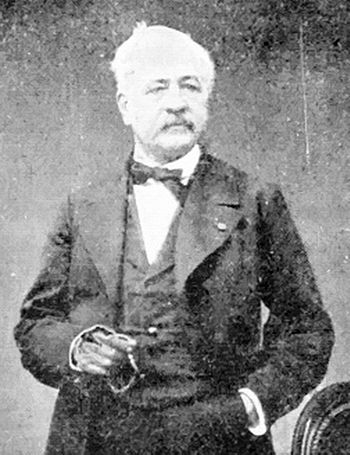

Except for these two short visits, which together covered barely two months, de Lesseps never set foot in Panama, but attempted to dig the canal from his office in Paris. Few people realize that to-day, or that de Lesseps was born as long ago as 1805. He was more than seventy years old, and though he knew very little about technical engineering, his success at Suez and the praise of flatterers made him believe that he was the greatest engineer in the world. As he had dominated the Congress, so he ruled the Canal Company, absolutely and blindly. Ignoring the great differences between the level, rainless sands of one isthmus, and the rocky hills and flooded jungles of the other, de Lesseps declared that "the Panama Canal will be more easily begun, finished, and maintained than the Suez Canal." The proposed canal was to be a ditch dug down to twenty-seven and a half feet below sea-level, seventy-two feet wide at the bottom, and ninety at the water-line. In general, it was to follow the line of the Panama Railroad, from ocean to ocean. To keep the canal from being flooded by the Chagres, a great dam was to be built across that river at a place not far below Cruces, called Gamboa. Because of the difference between the tides of the two oceans, a large tidal basin was to be dug out of the swamps on the Pacific side, where the rise and fall is ten times that on the Atlantic.

COUNT DE LESSEPS IN 1880.

DREDGE ABANDONED BY THE FRENCH AND REPAIRED BY THE AMERICANS.

The man in front of it did the job.

trusting in the word of the "great Frenchman" hundreds of thousands of his countrymen invested their savings in the worthless stock of the Canal Company. But the only persons who made any money out of the enterprise were the swindlers and speculators who used the deluded old man's honored name as a bait for other people's money. De Lesseps himself was honest, but so blinded by the memory of his past success that he could see nothing in Panama but another Suez.

Thousands of laborers and millions of dollars' worth of machinery were sent to the Isthmus, before the slightest preparation had been made to receive them. The Panama Railroad refused to carry these men and materials except as ordinary passengers and freight, at its own high rates. This soon forced the French Canal Company to buy the railroad, paying for it, including termini, $25,000,000, or more than three times what it cost to build it. The organization and management of the road, however, still remained American.

This lack of foresight was the first great cause of the French failure, and the second was disease. From the beginning, yellow fever and malaria broke out in every labor camp, and attacked almost every engineer and workman, killing hundreds, and demoralizing the rest. At that time, no one knew how to prevent these diseases, but the French tried their best to cure those that fell sick. They built two splendid hospitals, one on terraces laid out on the side of Ancon Hill, overlooking the city of Panama, and the other on piles out over the water of Limon Bay at Colon. In these hospitals, the feet of the cots were placed in little pans of water to keep ants and other insects from crawling up, and no one noticed the mosquito "wrigglers" swarming in the stagnant water of these pans, or in the many ornamental bowls of flowers. But when a fever patient was brought into the hospital, the mosquitos bred there would suck the poison from his blood, and quickly spread it through the unscreened wards. Malaria means "bad air," and the French in Panama thought it was caused by the thick white mist that crept at night over the surface of the marshes, and men spoke with terror of this harmless fog and called it "Creeping Johnny." Every evening the Sisters of Charity who acted as nurses—good, pious women, but ignorant and untrained—would close all the doors and windows tight to keep out the terrible Creeping Johnny, and then leave their patients to spend the night without either attendance or fresh air. Too often there was more than one corpse to carry out in the morning.

No proper attention was paid to feeding the force, and there was altogether too little good food, and too much bad liquor. Such a combination is harmful enough anywhere, but in the tropics it is deadly. And there was no lack of other evils to make it deadlier.

"From the time that operations were well under way until the end, the state of things was like the life at 'Red Hoss Mountain,' described by Eugene Field,

<poem>

When the money flowed like likker . . .

With the joints all throwed wide open 'nd no sheriff to

demur!

"Vice flourished. Gambling of every kind, and every other form of wickedness were common day and night. The blush of shame became virtually unknown. That violence was not more frequent will forever remain a wonder; but strange to say, in the midst of this carnival of depravity, life and property were comparatively safe. These were facts of which I was a constant witness."[1]

This state of affairs naturally caused a great loss of life; exactly how great it is difficult to determine. As in the case of the building of the Panama Railroad, there has been much exaggeration and wild guessing. After careful research, the Secretary of the Isthmian Canal Commission estimated the number of deaths among the French and their employees at from fifteen to twenty thousand.

The third great cause of the failure of the French Canal Company was graft. Every one connected with it was extravagant, and very few except M. de Lesseps were honest. More money was spent in Paris than ever reached the Isthmus, and what did come was wasted on almost everything but excavation. The pay roll was full of the names of employees whose hardest work was to draw their salaries. "There is enough bureaucratic work and there are enough officers on the Isthmus to furnish at least one dozen first-class republics with officials for all their departments. The expenditure has been simply colossal. One director-general lived in a mansion that cost over $100,000; his pay was $50,000 a year, and every time he went out on the line he had fifty dollars a day additional. He traveled in a handsome Pullman car, specially constructed, which was reported to have cost some $42,000. Later, wishing a summer residence, a most expensive building was put up near La Boca (now Balboa). The preparation of the grounds, the building, and the roads thereto, cost upwards of $150,000."[2]

When the Americans came to the Isthmus, they found three of these private Pullmans, on a railroad scarcely fifty miles long; a stableful of carriages, and acres of ornamental grounds, with avenues shaded by beautiful royal palms from Cuba. There was one warehouse full of what looked like wooden snow-shovels, but were probably designed for shoveling sand, which is not found on the canal line, and in another were several thousand oil torches for the parade at the opening of the Canal. When we consider these things, the wonder is, not that the French failed to dig the Canal, but that they dug as much as they did. Our army engineers speak very highly of their predecessors' plans and surveys. The French suffered, like the Scotch in Darien, from the lack of a leader, for there was usually a new chief engineer every six months, and the work was split up among six large contractors and many small ones. Though the engineers who directed the work were French, the two contractors who did most of the digging were not. It was a Dutch firm (Artigue, Sonderegger & Co.) that took a surprisingly large quantity of dirt out of the Gaillard Cut, with clumsy excavators that could only work in soft ground, and little Belgian locomotives and cars that look as if they came out of a toy-shop. The dredges and other floating equipment were much better, and many of them are still in use. Most of these dredges were built in Scotland. But it was an American firm (the

FRENCH METHOD OF EXCAVATION IN THE CULEBRA CUT.

American Dredging and Contracting Co.) that dredged the opening of the Canal from Colon to beyond Gatun. This company was the only contractor that made an honest profit out of the enterprise, and its big homemade, wooden dredges had cut fourteen miles inland, when the smash came in 1889.

Instead of the $120,000,000 originally asked for by M. de Lesseps, he had received and spent over $260,000,000. Instead of completing the Canal in six years, his company had dug less than a quarter of it in nine. Not a stone had been laid on the proposed great dam at Gamboa. Nothing had been done on the tidal basin except to discover that a few feet under what the Technical Commission had supposed to be an easily dredged swamp lay a solid ledge of hard rock. Year after year M. de Lesseps had kept explaining, and putting off the opening of the Canal, and asking for more money, until more had been spent than any possible traffic through the Canal could pay a profit on. Instead of finding Panama an easier task than Suez, the French had already dug 80,000,000 cubic yards, several million more than they did at Suez, and spent more than twice as much money. It was plain that the end had come. The French fled from the Isthmus, leaving it strewn as with the wreckage of a retreating army. Trains of dump cars stood rusting on sidings, or lay tumbled in heaps at the bottom of embankments. In one place, over fifty vine-covered locomotives can be counted at the edge of the jungle, from which the Americans dug out miles of narrow-gage track, cars, engines, and even a whole lost town. A lagoon near Colon was crammed with sunken barges and dredges. Others were abandoned at the Pacific entrance, or tied up to the banks of the Chagres, where the shifting of the river left some of them far inland. Thousands of Jamaican negroes who had worked on the Canal had no money with which to return home, and either went back to the West Indies at the expense of the British Government, or else built huts and settled down in the jungle.

A receiver was appointed for the French Canal Company, and a careful investigation made of its affairs. Criminal charges were brought against de Lesseps, who was convicted and sentenced to five years' imprisonment. But the sentence was never enforced against the old and broken-hearted man, and in a few months he died. Thousands of poor people were ruined. As for the real culprits, several committed suicide, and others were fined and imprisoned. Among those found guilty were so many senators, deputies, and other members of the French Government that for a short time there seemed danger of a revolution and the overturning of the Republic.

As most of the assets in the hands of the receiver consisted of the equipment and the work already done on the Isthmus, it was his duty to see that the enterprise was continued. So the French Government permitted the formation of the New Panama Canal Company out of the wreckage of the old one. This company took over all the machinery and buildings on the Isthmus, and in 1894 secured a concession from Colombia to finish the Canal in ten years.

The New Panama Canal Company went to work in the right way, and made most of the excellent surveys for which our engineers, who have found them extremely valuable, have given so much credit to their French predecessors. But the new company had so little money that it could keep only a few hundred men and two or three excavators busy in the Cut. It became plainer every year that the Canal could never be finished by 1904, and that the company's only hope was to find a purchaser. And every one knew that the only possible purchaser was the United States Government.