Panama, past and present/Chapter 9

CHAPTER IX

HOW THE AMERICANS BUILT THE PANAMA RAILROAD

PANAMA was the last stronghold, as it had been the first colony, of Spain in the three Americas, but when the Isthmus somewhat languidly declared its independence in 1821, the commander of the royal troops did not consider the former "Treasure-House of the World" worth the snap of a flint-lock. For since 1740, when trade had left it for the Cape Horn route, Panama had withered up into a place of almost no importance. Now that the old Spanish prohibition of foreign trade was removed, the Isthmus expected to share with the rest of Spanish America in a great commercial revival.

But though foreign ships now came to the village at the mouth of the Chagres, for which Porto Bello was presently abandoned, the difficulty of getting their cargoes across the Isthmus was too great. Many schemes were advanced for building a horse-car line or digging a canal, but nothing ever came of them. Year after year, the torpid little community lay between its two oceans and "drowsed the long tides idle," till it woke to new life with the discovery of gold in California, and the coming of the Forty-niners.

Thousands of Americans were poled and paddled up the Chagres in overcrowded dugouts to Cruces, and rode over the old paved road, now no better than a worn-out trail, to Panama City. So rough was the road that the mules could scarcely scramble over it, and many passengers preferred to be carried in chairs on the backs of negro or Indian porters. Four nights were usually spent on the journey across the Isthmus, nights of

From Harper's Magazine, by special permission of the publishers.

SURVEYING FOR THE PANAMA RAILROAD IN 1850.

crowded discomfort in native huts, where hammocks were rented for two dollars, and eggs cost twenty-five cents apiece. Panama was crammed with red-shirted Americans, who often waited months for a ship to take them to San Francisco, where ships were rotting three-deep at the wharves, while their crews went gold-hunting. To pass the time, the Yankees scratched their names on the ramparts of the sea-wall, and started two papers, the Star and the Herald, which, after a brief rivalry, combined in the present Panama Star and Herald, a daily, printed in both Spanish and English. Trade boomed, brigandage flourished, and there was more hiring of mules, renting of lodgings, raising of prices, and fleecing of strangers, than the Isthmus had seen since the roaring days of the Galleon Fair.

As soon as California and Oregon had been taken into the Union, Congress had authorized a line of steamers to be run down either coast to the Isthmus, and had appropriated money to pay them for carrying the United States mail. Mr. William H. Aspinwall, who had secured the line on the Pacific side, and Mr. George Law, who had that on the Atlantic, combined with a third New York capitalist, Mr. Henry Chauncey, to build a railroad across the Isthmus. Chauncey and John L. Stephens, an experienced Central American traveler, had already obtained from the government of the Republic of New Granada, of which Panama was now a state, the exclusive right to build such a road; and Stephens had explored the route with a skilled engineer, Mr. J. L. Baldwin, and reported that it could be built at a profitable cost.

The Panama Railroad Company was accordingly incorporated, with a New York charter and a capital of a million dollars, and the construction of the road entrusted to two experienced contractors, Colonel Totten and Mr. Trautwine. But no sooner had they reached the Isthmus than they found that the "gold-rush," now fairly begun, had so raised the local prices of labor and materials that they begged the company to release them

From Harper's Magazine, by special permission of the publishers.

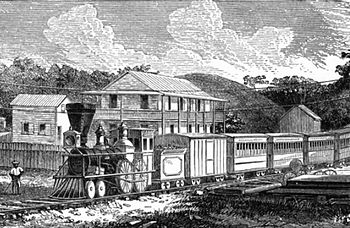

PANAMA RAILROAD IN 1855.

from the contract. This was done, and they were retained as engineers of the company, which proceeded to build the road itself.

A later survey by Baldwin and Colonel Hughes, who had been detailed from the United States Topographical Corps, had located the Pacific terminus at Panama City, and the Atlantic end at Navy or Limon Bay, between the mouth of the Chagres and Porto Bello. On Manzanillo Island in this bay, some time in the month of May, 1850, Trautwine and Baldwin struck the first blow.

"No imposing ceremony inaugurated the breaking ground. Two American citizens, leaping, ax in hand, from a native canoe upon a wild and desolate island, their retinue consisting of half a dozen Indians, who clear the path with rude knives, strike their glittering axes into the nearest tree; the rapid blows reverberate from shore to shore, and the stately cocoa crashes upon the beach. Thus unostentatiously was announced the commencement of a railway, which, from the interests and difficulties involved, might well be looked upon as one of the grandest and boldest enterprises ever attempted."[1]

Space was cleared for the erection of a storehouse, but so unhealthy was the low, swampy coral island, awash at high tide, and breeding swarms of malaria-spreading mosquitos, that the force were obliged to live on the two-hundred ton brig that had brought them and their supplies from New York. When Colonel Totten and Mr. Stephens, who had been made president of the company, arrived with more laborers from Cartagena, the little brig became uncomfortably overcrowded, and was replaced with the hull of a condemned steamer, the Telegraph, brought round from the mouth of the Chagres.

"Surveys of the island and adjacent country were now pushed vigorously forward. It was in the depth of the rainy season, and the working parties, in addition to being constantly drenched from above, were forced to wade in from two to four feet of mud and water, over the mangrove swamps and tangled vines of the imperfect openings cut by the natives, who, with their machetes, preceded them to clear the way. Then, at night,

FRENCH LOCOMOTIVES AND MACHINES

Left to rust in the jungle, near Empire.

rated and exhausted, they dragged themselves back to their quarters on the Telegraph, to toss until morning among the pitiless insects. Numbers were daily taken down with fever; and, notwithstanding that the whole working party was changed weekly, large accessions were constantly needed to keep up the required force. The works were alternately in charge of Messrs. Totten and Baldwin, one attending to the duty while the other recuperated from his last attack of fever."[2]

So they drove the line, over a trestle to the mainland, through the marshy lowlands to firmer ground at Mount Hope or Monkey Hill, then half built, half floated it over the deep Black Swamp to the banks of the Chagres at Gatun. A couple of ship loads of materials had been brought up the river to this point (now buried under the great dam) and by the first of October, 1851, the rails had been laid and working trains were running as far as Gatun. Two large passenger steamers, unable to cross the bar of the Chagres in a storm, were forced to put into Limon Bay, and their passengers, over a thousand in number, were only too glad to ride on flat-cars to Gatun and begin their river journey there.

When news of this unexpected passenger traffic reached New York, it sent up the value of the company's stock, which had fallen very low, for the original million dollars had been spent, and the road was far from completion. Now the steamers came reguarly to Navy Bay, where docks had been built, and a settlement had grown up as the island was cleared. Mr. Stephens proposed that this town be given the name of one of the founders of the railroad, and on the second of February, 1852, it became the city of Aspinwall. This name, however, was never recognized by the native authorities, who insisted on naming the place after Columbus, the discoverer of Limon Bay. Finally, after many years of trouble for the map-makers, the native government won the day by

From Harper's Magazine, by special permission of the publishers.

GATUN STATION.

Panama Railroad in 1855.

refusing to deliver any more mail addressed to "Aspinwall," and the city is now called Colon, as the Spaniards called Columbus.

The road was pushed on along the bank of the Chagres to a place called Barbacoas, an Indian word meaning "bridge." And here a bridge three hundred feet long had to be built over a river that sometimes rose forty feet in a single night. About this time Mr. John L. Stephens died, and his successor tried the experiment of having the great bridge and the remainder of the line built by contract. But after a valuable year had been wasted, not a tenth had been completed, and the contractors were bankrupt. Releasing them, the company, under a third and stronger president, set out to finish the work itself.

Every effort was made to assemble a strong working force, and recruits were brought from the four corners of the earth. But northern whitemen are not made for pick and shovel labor in the tropics, and the hundreds of sturdy Irish and European peasants did little but die of heat and malaria. Much was expected from a thousand Chinese coolies, but they became so demoralized by the death of some of their number from fever, in this strange and terrible land, that they were seized with a passion for suicide, and scarcely two hundred left the Isthmus alive. Some work was done by coolies from India, but the best workmen were found to be negroes from Jamaica and other islands in the West Indies.

There is a popular fable, that will be told and believed as long as the Chagres runs to the sea, that the building of the Panama Railroad cost a life for every tie. But there were about a hundred and fifty thousand ties in the fifty miles of single track, and there have never been that many inhabitants on the Isthmus since Pedrarias the Cruel killed off the Indians. As a matter of fact and record, the total number employed, from the beginning of the work to the end, was about six thousand; and the number of deaths eight hundred and thirty-five. Doubtless many others sickened on the Isthmus, and died soon after they left it, but even so, the health of the force was remarkably good, for men toiling in a tropical swamp at a time when no doctor knew how to fight malaria and yellow fever. There was besides no cold storage to preserve the food, almost every mouthful of which had to be brought two thousand miles from New York.

A bridge of massive timbers was thrown across the

From Harper's Magazine, by special permission of the publishers.

SAN PABLO STATION.

Panama Railroad in 1855.

Chagres at Barbacoas, and the road pushed on to the crest of the divide, at Culebra. In the meanwhile, men and materials had been shipped round the Horn, and eleven miles of track were laid from Panama to Culebra. Here, "on the twenty-seventh day of January, 1855, at midnight, in darkness and rain, the last rail was laid, and on the following day a locomotive passed from ocean to ocean."[3]

FRENCH DREDGES TIED UP TO THE BANK AFTER THE COLLAPSE OF DE LESSEPS COMPANY.

But, though open, the railroad was far from being completed. Ravines were crossed on crazy trestles of green timber, the track was unballasted, and there was a great lack of both engines and cars. So the superintendent recommended that, until they were better able to handle traffic, most of it be kept away by charging the very high rates of fifty cents a mile for passengers, five cents a pound for baggage, and fifty cents a cubic foot for freight.

"To his surprise, these provisional rates were adopted; and, what is more, they remained in force for more than twenty years. It was found just as easy to get large rates as small; and thus, without looking very much to the future, this goose soon began to lay golden eggs with astonishing extravagance. The road was put in good order, with track foremen established in neat cottages four or five miles apart, along the whole line. New engines and cars were put on, commodious terminal wharves and other buildings provided, and all things were in excellent shape."[4] Trestles were made into solid embankments and wooden bridges replaced with iron; the great girder bridge at Barbacoas being the wonder of the time. Instead of pine, too quickly eaten up by ants, the ties were made of lignum-vitæ, so hard that holes had to be bored before the spikes could be driven.[5] The telegraph poles were made of cement, molded round a pine scantling, a device that seems strangely modern.

Instead of one million dollars, the total cost of building this fifty-mile railroad was eight millions. But even before the first through track was laid, it had earned two million dollars' worth of fares, and during the first ten years of its existence, it took in $11,339,662.78. This was the Golden Age of the Panama Railroad, when it enjoyed the monopoly of the Atlantic trade, not only of California, but the entire west coast of the three Americas.

From Harper's Magazine, by special permission of the publishers.

TERMINUS AT PANAMA.

Panama Railroad in 1855.

Its stock earned dividends of twenty-four per cent, a year, and was considered one of the safest investments in Wall Street.

But in the contract made between John L. Stephens and the government of New Granada, that government had been given the right to buy the Panama Railroad, twenty years after it was opened, for five million dollars—and it was now paying twenty-four per cent, on seven million dollars' worth of stock! At the end of the twelfth year, Colonel Totten went to Bogotá, the capital, and succeeded in obtaining a new franchise for ninety-nine years, but at the heavy cost of a million down and two hundred and fifty thousand a year, with the additional obligation of extending the railroad to the islands in the Bay of Panama.

Two years later came the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad, and the loss of the California trade. But far more important than this was the traffic with the west coast of South and Central America, carried almost entirely by the ships of a British corporation, the Pacific Steam Navigation Company. The incredible stupidity of the Panama Railroad's directors forced this company to abandon its shops and dockyards on the Island of Taboga, in the Bay of Panama, and send its ships direct to England through the Straits of Magellan. Too late they saw that most of the trade went with them.

So, like Spain, the Panama Railroad built a trade-route across the Isthmus, monopolized it, flourished, and decayed. Its once-prized stock became the football of Wall Street speculators, its tracks the traditional "two streaks of rust." But unlike Spain's, its star was to rise again.