Savage Island/Appendix

APPENDIX

TONGAN MUSIC

THE music of the Tongans was inseparable from the dance (by which I mean the rhythmic movements of any part of the body), and it therefore esteemed rhythm before melody or harmony. There were two principal forms, the Me‘e-tu‘u-baki (dance standing up with paddles) and the Otuhaka (song, with gestures). Since the inculcation of English hymn-singing a third form, known as the Lakalaka, which is music composed by Tongans on the European model, has been introduced, and of this the Tongans are inordinately fond. Fortunately the taste of the older chiefs and the influence of the French missionaries have been strong enough to preserve the old forms intact, and both the Me‘e-tu‘u-baki and the Otuhaka are given on ceremonial occasions, though their ultimate decay is certain.

The specimens of Polynesian music that have found their way into the text-books are, from Mariner downward, nearly all inaccurate. Written down by untrained musicians, they have afterwards been "faked" to bring them into line with our notation, and (infamy of infamies) harmonised! The visit of a composer with time on his hands and a patient determination to record the native music faithfully, at any sacrifice of time and temper, was an opportunity not to be neglected. Soon after our arrival, therefore, we paid a visit to Mua, where the old music is most cultivated, and invited the people to entertain us with the Lakalaka, for we had naval officers with us, and the Otuhaka is strong meat for the uninitiated. At the close of the performance I sent for the leader, Finease (which is Phineas), and unfolded my proposal, which was that, for value to be received, he and a select band of musicians of the old school should come to Nukualofa and sing without ceasing until they had yielded up their treasures to the paper. Plainly they thought it a fatuous proceeding, but they consented lightly, not knowing what lay before them.

Three mornings later we were at work in the huge wooden shed which serves Dr. Maclennan as operating-room and hospital. At the further end lay two patients who had undergone serious operations on the previous afternoon; what they thought of our proceedings I do not know, but I could make a shrewd guess from the expression of the old ladies who were nursing them. Amherst Webber sat at a deal table littered with music-paper, with Phineas and three middle-aged ladies, all noted singers, sitting in a row on the floor before him. He wore a harassed air, for it soon transpired that the ladies, thinking that they knew better than he did what he wanted, were bent on running through their répertoire without encore. When I explained that they would have to sing each phrase, not twice, but perhaps forty times over, they were at first amused and afterwards distinctly bored. Webber found it impossible to take the music down phrase by phrase, because they were incapable of picking up the melody where they had left it; the only way was to make them begin each time at the beginning, and carry the score a few notes further with every repetition. Moreover, it was discovered that Phineas seldom sang the same phrase in exactly the same notes, for the melody is overlaid with innumerable turns and ornaments at the will of the singer, and these are impossible to represent in our notation. Two hours at a time being as much as writer or singer could stand with safety, the work took several days, but, thanks to the good sense of Phineas and the patience of Webber, a valuable collection was ultimately made. For the notes I am, of course, indebted to Amherst Webber.

1. THE "ME‘E-TU‘U-BAKI,"

A good drawing of this dance is to be found in Cook's Voyages, and, as Mariner also has described it, I need say no more than that it is performed by men, drawn up in one line or two, who perform certain slow and stately evolutions, accompanying the music by twirling a light wooden instrument carved in the shape of a paddle. The rhythm is set by three large wooden drums, and a number of men sitting round them sing the words, which consist generally of a single phrase, endlessly reiterated. Unlike the Otukaka, the Me‘e-tu‘u-baki is not contrapuntal, and, though a number of voices maintain one note while the others sing the melody, it may be said to be sung in unison. To the European ear, despite its marked character, it is indescribably monotonous, for the words have no meaning, and the phrase is repeated for twenty minutes at a stretch, without any variation except an occasional crescendo. The native, however, regarding it as a mere accompaniment, concentrates his attention on the dance, which, though also monotonous to our eyes, is full of ancient grace and dignity to his.

MEE-TUU-BAKI.

![<< \new Staff { \key a \minor \time 2/4 \relative c' { r4 c8 d | \afterGrace c4 { d16[ c] } a8 a | r4 c8 d16 c | \afterGrace e4 { f16[ e d] } c8 a

\repeat volta 2 { d2 ~ d8 r c d |

\afterGrace c4 { d16[ c] } a8 a | r4 c8 d16 c |

\afterGrace e4 { f16[ e d] } c8 a }

d2 ~ d4 \bar "|." } }

\new Staff << \clef bass \key a \minor \new Voice { \stemUp r4 a8 a | a4 a8 a | a a a a | r4 a8 a | a2 ~ a8 r a a | a4 a8 a | a a a a | r4 a8 a | a2 ~ a4 }

\new Voice { \set midiInstrument = #"woodblock" \relative a, { \tiny \stemDown a4_"Drum." a8 a \repeat unfold 6 { a4 a8 a } a8 a a a | a4 a8 a | a4 a8 a | a4 } } >> >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/3/y/3yo0qowczwtts3bqpd8z4t3subi1hr0/3yo0qowc.png)

2. THE "OTUHAKA."

Though it may be performed standing, the singers of the Otuhaka generally sit in a single line, loaded with garlands and anointed with scented oil. The feature of the performance is the haka, or gesture-dance, for though the performers may be sitting, it is still a dance. Head, eyes, arms, fingers, knees, and even toes all have their part, and the precision of the gestures is extraordinary. The talent may be said to be born in every Tongan, for you may see little mites of eight years old shyly take their places at the end of the row and acquit themselves without a slip. The Otuhaka opens with a long and threatening solo on the drum, consisting of the same bar insistently repeated. After thirty bars or so the gesture dance begins in silence to the same monotonous accompaniment, until at last, when you have almost given up hope of anything more, the leader bursts into song, the rhythm of the drum never varying until it quickens up towards the end. All the performers sing; the leader takes the melody, and the chorus the second part, for the Otuhaka, which are generally of the same form, are always in two parts, and usually in rough canon. Here, too, there is an interminable repetition of the same theme until the leader gives the signal for a change by striking a higher note, and then the gestures change, the time quickens, and the chorus breaks into the tali, or coda, ending with a long-drawn note and a sudden dropping of the voice down the scale, like an organ when the bellows give out. The time is generally common or two-four, but in one of the examples given below the time is three-eight.

In reading these examples it is to be remembered that the leader loads his melody with turns and grace notes which are never quite the same, and which are impossible to write down, and further, that the final note always ends with the peculiar groan which I have described.

| ||

| From a photograph by | THE OTUHAKA | J. Martin, Auckland |

| The two drummers sit in the middle of the semicircle | To face page 222 | |

OTUHAKA (1)

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

OTUHAKA (2) Koe Kolo Kakala.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

OTUHAKA in three-eight time.

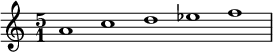

From these examples it will be seen that the old Tongan scale is limited to the following notes:—

In the absence of any indication of the chord, it would be incorrect to speak of tonic or dominant, but if we assume the key to be C minor, we may say that the Tongans have no fifth, nor leading note, and that they are not enamoured of the fourth. It is not that any of these intervals are abhorrent, for, as we shall presently see, they have taken very kindly to our notation in the Lakalaka, where a progression of consecutive fifths seems to afford them peculiar delight. The character of their music is contrapuntal and not harmonic, though in their church music they are intensely fond of the full chord. The intonation in singing is very nasal, and though the men were easily taught to correct this fault in singing European music, the women are incorrigible. The explanation offered to me by a native lady was that opening the mouth wide while singing swelled a disfiguring vein in the throat, but I suspect the real reason to be that which prompts them to conceal a yawn behind the hand—namely, that it is indelicate to expose the inside of the mouth to public gaze.

3. THE "LAKALAKA."

The only interesting feature in the Lakalaka lies in the fact that it is music composed by natives under the influence of European music. It shows little talent or invention, and its more ambitious melodies and crude harmonies, however spirited the performance, pall quite as quickly as the Otuhaka, which has at least a weird and striking character of its own. The composer of the Lakalaka is at once poet and dancing-master as well as composer. When the afflatus is upon him he retires to the bush, and returns with words, music, and appropriate gestures complete in his head, and an hour's practice suffices to make all the boys and girls in his village perfect in their parts. Finease Fuji was one of these, and his reputation ensured a public performance to all his compositions. Those that become popular may endure for many years. Langa fale kakala (build a house of flowers), for example, which is given below, is as popular a favourite now as it was when I was in Mua in 1886. The themes are boating songs, odes to Nature and to flowers, or laments, but never love-songs. I remember one very pathetic lamentation of a poet named Tubou, whose theme was a term of six months' hard labour awarded him for flirting; it attained immense popularity on account of its pathos; indeed, I think that the pathetic Lakalaka are the most enduring. Love-songs are called sipi, and they are never sung in public, being rather in the nature of sonnets to my lady's eyebrow.

Like the Otukaka, the Lakalaka is in two parts, though the voices may divide into four parts in the final chord. They are contrapuntal in form as well as harmonic, and they are accompanied with the same kind of gesture dance as the Otuhaka. The singers may either sit or stand in one or two rows; if they stand, the men go through a sort of dance, while the women move their heads and arms without changing their position. The difference between the two forms lies in the scale, for the Lakalaka makes use of our scale both major and minor, with the exception of the leading note, which is generally omitted; the melody is more sustained, and, no drum being used in accompaniment, the rhythm is less marked.

The European music which have been the foundation of the Lakalaka are Wesleyan hymns, military band marches, and Mozart's Twelfth Mass, which is very well done by the students of the Wesleyan College. Most of the educated natives can read very well in the tonic sol-fa notation, and they have now begun to compose a kind of choral anthem for themselves, which is very much like the Lakalaka without the gestures. They show a great aptitude for keeping their parts, even in complicated counterpoint. That they have a strong natural turn for music is certain; it is the exception to find a native without a voice and a correct ear, and if they lack originality themselves, they have at least a very quick appreciation. I have described elsewhere[1] how the Grand March from Tännhauser took them by storm when it was first performed, albeit imperfectly, by the king's band. LAKALAKA.

by FINEASE FUJI of MUA.

![<< \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \new Staff { \tempo \markup { \italic \smaller Allegro } \time 4/4 \key c \major \relative g { \repeat volta 2 { \times 2/3 { r8 g g } g \afterGrace c { d16[ e] } d4 \times 2/3 { c8 c c } |

\afterGrace e4 { f16[ e] } d8 e \times 2/3 { \afterGrace e8[ { f16[ e] } d8 c] } b c |

\times 2/3 { d8[ c] d ~ } \times 2/3 { d c c } c r8 r4 }

\time 12/8 \repeat unfold 2 { g'4. ~ g8[ \afterGrace g { a16[ g f] } e8] \afterGrace e[ { f16[ e d] } c8 c] d4 \times 2/3 { e16 f e } |

d4 \times 2/3 { e16 f e } d8( c) c c r r r4 r8 | }

\repeat unfold 2 { r8 a'4^> ~ a8 g f a g g g g g |

e e f g g g g g g g r r | }

e d e c d d e e \afterGrace e { f16[ e] } d4 c8 |

c4. ~ c8 r r r4 r8 r4 r8 \bar "|." } }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key c \major \relative c { r4 c8 c c4 \times 2/3 { e8 e f } |

g4 f8 g \times 2/3 { g f e } g g |

\times 2/3 { f[ e] g ~ } \times 2/3 { g c, c } c r r4 |

r4 r8 c' c a a a a g4 g8 |

g g a c c c c c c c c, r |

r4 r8 c' c a a a a g4 g8 |

g g a c c c c d c \afterGrace a[ { b16[ a] } g8 g] |

g r c c c c c c c c c c |

g g a c c c c r r r4 r8 |

r4 c8 c c c c c c c c c |

g g a c c c c r r r4 r8 |

g f g e f f g g g g4 c,8 |

c4. ~ c8 r r r4 r8 r4 r8 } } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/d/edz4hj3z3ktq9yh5xg5drng3hr51bub/edz4hj3z.png)

- ↑ The Diversions of a Prime Minister.