Syria, the Land of Lebanon/Chapter 12

CHAPTER XII

THE CEDARS OF THE LORD

WE had watered our horses, eaten the last olive and the last scrap of dusty bread that remained in the bottom of our saddle-bags, and were shivering and impatient and irritable; for a sea of beautiful but chilling clouds was rolling around us, and as yet there was no sound of the far-off tinkle that would herald the approach of the belated mule-train which bore our tents and food.

Then suddenly, just as the sun was setting, a friendly breeze swept the clouds down into the valleys; and in a moment fatigue, vexation and hunger were forgotten, as we contemplated one of the most beautiful panoramas in all Lebanon. Before us the mountain sloped quickly to a precipice whose foot lay unseen, thousands of feet below, while just across the gorge, so steep and lofty and apparently so near as almost to be oppressive, towered Jebel el-Arz—the Cedar Mountain. The whole range was bathed in a wonderful golden hue, more brilliant yet more ethereal than the alpenglow of Switzerland. Soon the gold faded into blue, and that to a Tyrian purple, a color so royal that those who have not seen cannot believe, so deep and strange that, to those who have seen, it seems almost unearthly. One must gaze and gaze in a vain attempt to fathom its unsearchable depths, until the purple darkens into black, and the watcher stands silent, as if the setting sun had for a moment swung open the door that leads into the eternal.

"Where are the cedars?" I asked a member of our party who had visited them before.

"Over there, directly in front of you!"

"But the mountain seems to be one bare, empty mass of rock!"

"Look closer—yonder—where I am pointing!"

Yes, there they are, apparently hung against the face of the rock in such a precarious situation that a loosened cone would drop clear of the little ledge and fall all the way to the bottom of the valley. You see just a tiny patch of dark green against the mountainside—as big as the palm of your hand—no, as large as a finger nail—like a speck on the lens of a field-glass. Such is the first view of the group of ancient trees which are still known as the "Cedars of the Lord."

While we were engrossed with the mountain scenery, the baggage-train at last appeared. Then came that most satisfyingly luxurious experience, a camp dinner after a long, wearisome day in the saddle. We supplemented our canned food by purchases made at the near-by village of Diman, where we procured delicious grapes, tomatoes, fresh milk, and new-laid eggs at six cents a dozen.

After dinner a young Maronite priest came up from the convent to visit us. Father Abdullah proved to be the private secretary of the patriarch, who has a summer residence at Diman. It was an unanticipated experience for us to meet, high up in this wild mountain region, a Syrian priest who, after graduating from the Maronite College at Beirut, had spent seven years in advanced Latin studies at Paris and had then read archæology at the British Museum. Father Abdullah's English, however, was a broken reed; so most of our conversation was carried on in French, with an occasional lapse into Arabic. He said that his long residence at Paris had naturally brought him into closest sympathy with the French, but that nevertheless he considered the English superior in practicality and energy. He had recently made an independent archæological study of the surrounding district, and entertained us by telling some of his own theories concerning the very early history of Lebanon. Later in the evening, as a further evidence of his friendship, he sent us a great basket of fresh figs.

While we were enjoying this delicious gift, the fog rolled up again from the west and filled the gorge until we looked across the billowing surface of a milk-white sea, above which only a few of the loftiest peaks appeared as lonely islands. Such was the marvelous purity of the air at this altitude that even at night the sky was still a deep blue and the full moon touched the rocks with delicate tints of orange and rose, while, to complete the soft beauty of the scene, a double lunar rainbow swung its cold silvery arcs above the summit of the Cedar Mountain.

Then the wind freshened, the rising fog-waves overflowed from the valleys and the penetrating chill of our cloud-bound mountainside drove us to the shelter of our tents.

When we reached the cedar grove the next noon, we found that our first impressions had been wrong concerning everything except the supreme beauty of the mountain setting. Far from being situated upon a narrow shelf on a perilously steep slope, the trees are securely enthroned amid surroundings of massive grandeur. The watershed of Lebanon here curves around so that it encloses a tremendous natural amphitheater about twelve miles long and over six thousand feet in depth, with its inner, concave side facing the Mediterranean. High up on this crescent-shaped slope, the Kadisha or "Holy" River issues from a deep cave and falls to the bottom of the valley in a succession of beautiful cascades. Around the amphitheater run a succession of curving ledges, like titanic balconies, which near the bottom are small and fertile, but which become longer and broader and more barren toward the wind-swept summits. The highest of these, which lies nearly seven thousand feet above the sea, is eight miles long and at its widest three miles across. Though it is really broken by hundreds of hills, these are dwarfed into insignificance by the great peaks which rise behind them, and in a distant view the surface of the plateau seems perfectly level.

Here, amid surroundings of rare beauty and yet of solemn loneliness, is set the royal throne of the king of trees. Just back of the cedars the mountains rise to an elevation of over 11,000 feet. Around them is vast emptiness and silence. No other trees grow on this chill, wind-swept height. No under-brush springs up among their rugged trunks. The last cultivated fields stop just below, and the nearest village is out of sight and sound, far down the mountainside. A few goatherds lead their flocks to a near-by spring that is fed from the snow-pockets of the Cedar Mountain; but at night the wolves can be heard howling hungrily, and by the end of the year the snow drifts deep around the old trees and the passes are closed for the winter.

Yet downward from the cedars is a prospect of warm, fertile beauty. You look deep into the dark green valley of the Kadisha, and then across the lower mountains to where, thirty miles away, the "great sea in front of Lebanon"[1] rises high up into the sky; and during one memorable week in the summer you can see, a hundred and fifty miles across the Mediterranean, the jagged mountain peaks of the island of Cyprus outlined sharp against the red disk of the setting sun.

When the Old Testament writers wished to describe that which was consummately beautiful, rich, strong, proud and enduring, they drew their similes from Hermon and Lebanon, and the climax of the "glory of Lebanon" they found in the "cedars of God."[2] Would they express the full perfection of that which was choice,[3] excellent,[4] goodly,[5] high and lifted up,[6] they pictured "a cedar in Lebanon with fair branches, and with a forest-like shade. … Its stature was exalted above all of the trees of the field; and its boughs were multiplied, and its branches became long. … All the birds of the heavens made their nests in its boughs; and under its branches did all the beasts of the field bring forth their young. … Thus was it fair in its greatness, in the length of its branches … nor was any tree in the garden of God like unto it for beauty."[7]

The cedar of Lebanon must not be confounded with the various smaller trees which in America are known as "cedars." It is own brother to the great deodar or god-tree of the Himalayas and the forest giants on the high slopes of the Atlas, Taurus and Amanus ranges. In the days when Hiram of Tyre provided timber for Solomon's Temple, large cedar woods spread over Lebanon, and apparently grew also on the sides of Anti-Lebanon and Hermon; but generation after generation these trees became fewer in number. Even in the sixth century, Justinian found it difficult to secure sufficiently large beams for the Church of the Virgin (now the Mosque el-Aksa) in Jerusalem. Many efforts were made to preserve the trees, which had long been considered of a peculiar sanctity. High up on the rocky sides of Lebanon, Hadrian carved his imperial command that the groves should be left untouched. Modern Maronite patriarchs have excommunicated those who cut down the "trees of God." But the roving goats who nibble the tender young saplings have regarded neither emperor nor patriarch. Now there is little timber of any kind in Syria, and the profiles of the mountains cut sharp against the sky. Of the cedars there remain only seven groups, the finest of which is the one we are visiting, above the village of Besherreh.

A former governor of Lebanon, Rustum Pasha, protected this grove against roving animals by a well-built stone wall, and in recent years the number of young trees has consequently slightly increased. But the really old cedars grow fewer century by century; indeed, young and old together, their number is pathetically few. Twelve of the very largest are usually counted as the patriarchs of the grove. The mountaineers say that these had their origin when Christ and the eleven faithful Disciples once visited Lebanon, and each stuck his staff into the earth, where it took root and became an undying cedar. In all there are about four hundred trees. A local tradition says that they can never be counted twice alike; and, in fact, I have yet to find two travelers who agree as to the number. We need not, however, seek a miraculous explanation of this peculiar lack of unanimity. It is doubtless due to the fact that several trunks will grow so close together that no one can say whether they should be considered as a single tree, or as two or more. When no fewer than seven trunks almost touch at the bottom, it is quite impossible to tell whether they sprang originally from one seed or from many.

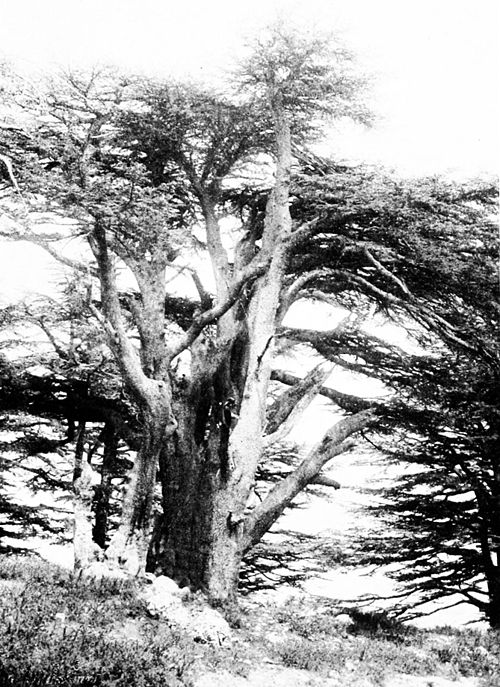

Yet though the cedars are few in number, these few are kingly trees. Their height is never more than a hundred feet; but some have trunks over forty feet around, and mighty, wide-spreading limbs which cover a circle two or three hundred feet in circumference. Those which have been unhindered in their growth are tall and symmetrical; others are gnarled and knotted, with room for the Swiss Family Robinson to keep house in their great forks. Some years ago a monk lived in a hollow of one of the trunks. When you climb a little way into a cedar and look out over the whorl of horizontal branches, the upper surface seems as smooth and soft as a rug, upon which have apparently fallen the uplifted cones. Indeed, The Cedar Mountain. The grove shows as a small, dark patch at the right

The source of the Kadisha River. The rocks in the background mark the edge of the plateau on which are situated the Cedars of Lebanon

the close-growing foliage will bear you almost as well as a carpeted floor. Eighty feet above the ground, I have thrown myself carelessly down, not upon a bough, but upon just the network of interlacing twigs, and rested as securely as if I had been lying in an enormous hammock.

Most of the cedars are crowded so closely that their growth has been very irregular. Sometimes two branches from different trees nib against each other until the bark is broken; then the exuding sap cements them together, and in the course of years they grow into each other so that you cannot tell where one tree ends and the other begins. Just over my tent two such Siamese Twins were joined by a common bough a foot in diameter. Near by I found three trees thus united, and another traveler reports having seen no fewer than four connected by a single horizontal branch which apparently drew its sap from all of the parent and foster-parent trunks. Even more remarkable is a cedar which has been burned completely through near the ground, and yet draws so much sap from an adjoining tree that its upper branches continue to bear considerable foliage.

The wood is slightly aromatic, hard, very close-grained, and takes a high polish. It literally never rots. The most striking characteristic of the cedars is their almost incredible vitality. The oldest of all are gnarled and twisted, but they have the rough strength of muscle-bound giants. Each year new cones rise above the broad, green branches, and the balsamic juice flows fresh from every break in the bark. In the words of the Psalmist, they still bring forth fruit in old age, and are full of sap and green. "There is not, and never has been, a rotten cedar. The wood is incorruptible. The imperishable cedar remains untouched by rot or insect." This is not the extravagant statement of a hurried tourist, but the sober judgment of the late Dr. George E. Post, who was recognized as the world's greatest authority on Syrian botany. The whole side of one of the largest trees has been torn away by lightning, but the barkless trunk is as hard as ever. The single enemy feared by a full-grown cedar is the thunderbolt. "The voice of Jehovah … breaketh in pieces the cedars of Lebanon."[8] One or two trees felled by this power have lain prostrate for a generation; but their wood will still turn the edge of a penknife. Here and there, visitors to the grove have stripped off a bit of bark and inscribed their names on the exposed wood. "Martin, 1769," "Girandin, 1791"—the edges of the letters are as hard and clear-cut as if they had been carved last season.

It is no wonder that the ancients chose this imperishable timber for their temples. The cedar roof of the sanctuary of Diana of Ephesus is said to have remained unrotted for four hundred years, while the beams of the Temple of Apollo at Utica lasted almost twelve centuries.

Probably the wood is so enduring because it grows so slowly. When you are told that a slender shoot, hardly shoulder-high, is ten or twelve years old, you begin to speculate as to the probable age of the patriarchs of the grove. On a broken branch only thirty inches in diameter I once, with the aid of a magnifying glass, counted 577 rings—577 years. And some of the cedars are forty feet and over in girth! Certainly these must be a thousand years old, probably two thousand. We are tempted to believe that one or two of the most venerable were saplings when the axemen of Hiram came cutting cedar logs for the Temple at Jerusalem. The most rugged and weather-beaten of them all, called the Guardian—surely this hoary giant of the forest has lived through all the ages since Solomon, and from his lofty throne on Lebanon has calmly looked down over Syria and the Great Sea while Jew and Assyrian, Persian and Egyptian, Greek and Roman, Arab and Crusader and Turk, have labored and fought and sinned and died for the possession of this goodly land!

The trees rise on half a dozen little knolls quite near to the edge of the plateau; and within a few minutes' climb are a number of tall, steeple-like rocks which, through the erosion of the softer stone, have become almost entirely cut off from the main mass of the mountain. One such group, known to American residents of Syria as the "Cathedral Rocks," is reached by following a knife-edge ridge far out over the valley. There is barely room for a narrow foot-path along the top, and a misstep would mean a fall of many hundred feet; but at its western end the ridge broadens out into a group of slender, tower-like cliffs. When you stand on the farthest of these there is a feeling of spaciousness and isolation as if you were indeed upon the loftiest pinnacle of some gigantic cathedral, though no man-built spire towers to such a dizzy height.

A half-hour of hard and, in places, dangerous climbing down from the cedars brings one to where the Kadisha River bursts from a cave in the rock. Like many another cavern in Lebanon, this is of great depth and has never been thoroughly explored. We contented ourselves with penetrating it a few hundred feet; for it was impossible to avoid slipping into the stream now and then, and the water, fresh from the snow-pockets on the summits above, was only twelve degrees above the freezing-point. The entrance is barely ten feet in diameter, but the cave soon divides into several branches, one of which is beautifully adorned with translucent stalactites and, about seventy yards from the mouth, leads up to a large rock-chamber. The river flows out from the mountain with great rapidity and, just below the source, leaps over a precipice in a white waterfall forty feet high, so delicate and lacelike in its beauty that it is known as the "Bridal Veil."

Farther down the valley, the monastery of Kanobin hugs the side of a cliff four hundred feet above the river-bed. This is literally "the monastery" (Greek, koinobion), and is one of the oldest in the land. It is said to have been founded over sixteen hundred years ago by the Roman emperor Theodosius the Great, and for centuries it has been the nominal seat of the Maronite patriarchs. In 1829, Asad esh-Shidiak, the first Protestant martyr of Lebanon, was walled up in a near-by cave. This unfortunate man was chained to the rock by his Maronite persecutors and about his neck was fastened one end of a long rope which hung out through an opening in the cave by the roadside. Each Catholic who passed by gave the rope a vicious tug, and Shidiak soon died of torture and starvation.

The valley of the Holy River is full of old hermits' caves; but these are now untenanted, and we found no monks even at the great convent. In a parallel valley, however, is a monastery which is still crowded and busy. Deir Keshaya boasts a printing-press, a good library and a staff of a hundred monks. This religious retreat has the most secluded and beautiful situation imaginable. It lies in a very narrow cañon hemmed in by sheer rocks. Yet, though surrounded by nature in its most grand and forbidding aspects, the narrow strip of cultivated land along the river bank is rich with verdure, a veritable Garden of the Lord.

The monastery not only spreads along the face of the cliff, but penetrates far into the mountain. What you see of it from without is hardly more than the façade of a huge, rambling structure whose principal part consists of natural caves and chambers rudely cut in the native rock. Through a little wooden door we were admitted to the largest cavern, where we saw, hanging from staples set securely into its walls, a number of great, cruel chains. People who are possessed of devils are fastened here by the neck and ankles, and during the night an angel comes and drives away the demon. The treatment has never been known to fail; for if the morning finds the sufferer still uncured, that merely shows that he did not have a devil after all, but was just an ordinary lunatic for whom the monastery did not promise relief.

Back of the cedars, there are also many fascinating excursions. The ranges of Syria being geologically "old" mountains which are worn and rounded, you can, by taking a somewhat circuitous route, reach almost any summit on horseback, but it is much more fun to go straight up the steepest slopes on foot. About 2,500 feet above the grove is a line of gently rolling plateaus whose stones have been broken and smoothed by millenniums of snow and ice. You see acre after acre entirely covered with clean, flat fragments which measure from one to five inches in length. Viewed from a distance, their appearance is exactly like that of the soft surface of a wheat-field. The only vegetable life consists of tiny bunches of a low, hardy plant with wooly gray-green leaves. We saw one little butterfly fluttering about lonesomely in the vast desolation.

Sheltered from sun and wind just under the highest ridges are snow-pockets—great, funnel-shaped depressions which during the hottest summer send down their moisture through the mountain mass to the cave-born rivers of western Syria. One who has not been there would never suspect how cold it can be in mid-summer on these higher slopes of Lebanon. The direct rays of the sun are, of course, very hot, and the wise traveler protects his head by a pith helmet. Yet the gloomy gorges are always chilly, the wind is biting, and the nights are positively cold. When tenting among the cedars, I slept regularly under heavy blankets, and once or twice reached down in the middle of the night and pulled over me the rug which lay beside my cot. The first time we climbed the mountain back of our camp, the wind was so cold and penetrating that we could remain only a few minutes on the summit, though we wore the heaviest of sweaters and had handkerchiefs tied over our faces.

At another ascent, however, we were more fortunate, for we found only a slight breeze blowing on the summit. The "Back of the Stick," as the natives call this highest ridge of Lebanon, affords a view over the top of all Syria. Northward stretches the long succession of rounded summits, down to the left of which can be seen the white houses of the seaport of Tripoli. To the south are other lofty peaks, though all are lower than ours. Jebel Sunnin, which seems so mighty when viewed from the harbor of Beirut, now lies far below us. Mount Hermon rises still majestic seventy miles away, yet even the topmost peak of great Hermon is not so high as the spot on which we stand. To the east, across the long, broad valley of the Bika', rises the parallel range of Anti-Lebanon. Westward the magnificent amphitheater which we have come to think of as peculiarly our own opens out to where the Mediterranean, like a sheet of beaten gold, seems to slope far up to the azure sky.

Yet, after a while, we turned from this wonderful panorama to indulge in childish play. With a crowbar brought for the purpose, we dislodged large rocks from the summit and sent them spinning down the eastern side of the mountain. Some of them must have weighed several tons, and they tumbled down the slope with tremendous momentum. The first thousand feet they almost took at a bound; then, reaching a more gentle decline, they would spin along on their edges. Now they would strike some inequality and, leaping a hundred yards, land amid a cloud of scattering stones; now they would burst in mid-air from centrifugal force, with a noise like a cannon shot; now some very large stone, surviving the perils of the descent, would arrive at the base of our peak and, on the apparently level plateau below, would very slowly roll and roll and roll as if it possessed some motive power of its own. Several days later we met a wandering shepherd who told us that, while dozing beneath the shade of a cliff far down the mountainside, he had been suddenly awakened by a terrific cannonading and had sat there for hours in trembling wonderment at the demoniac forces which were tumbling Mount Lebanon down over his head.

One evening we strolled out to the edge of our plateau and saw the whole countryside a-twinkle with lights. It was the anniversary of the Finding of the True Cross. When St. Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, discovered the precious relic sixteen hundred years ago, beacons prepared in anticipation of the success of the search were lighted and the glad news was thus flashed from Jerusalem to the emperor at Constantinople. In commemoration of that joyous event, annual signal fires still burn along the land of Lebanon. Far down in black gorges we saw the lights flash out. North and south of us, unseen villages on the hillsides kindled their beacons. Higher up, in wild pine forests, the lonely charcoal-burners made their camp-fires blaze brighter; and even on the bare, bleak summits there shone here and there tiny gleams of light. Amid the solemn quiet of our mountain solitude, we watched the beacons flash out around us and below us and above, until all Lebanon seemed starred with the bright memorials of the Cross which this old, old land, through long centuries of oppression and ignorance and bigotry, has never quite forgot.

We spent a month in the cedar grove, and never had a dull day. At dawn we could look out of the tent to where the green branches framed a charming bit of blue, distant sea. After breakfast the studious man would climb up into his favorite fork and ensconce himself there with pen and ink and paper and books and cushions. The adventurous man would scramble up to the topmost bough of some lofty tree and stretch out on its soft twigs for a sun-bath. The lazy man would curl up against a comfortable root, to smoke and dream away the morning hours. Sketching and photographing and mountain climbs were interspersed with unsuccessful hunting expeditions and aimless conversations with Maronite priests who had come up to visit their little rustic chapel in the grove. After supper came the camp-fire, with its cozy sparkle and its friendly confidences and the black background of the forest all around. Then, by eight o'clock at the latest, we snuggled into our blankets and, in the crisp, balsam-scented air, slept the clock around. Sometimes the full moon shone so brightly that the whole mountain would take on a soft silver glow, against which colors could be distinguished almost as well as by day. Now and then there would be a cold, foggy morning; but the trees kept out the mists and, although a solid wall of white surrounded us, within the grove it was clear and dry and homelike.

The shelter, the support, the background, the inspiration of all the camp life, were the great, solemn trees. After a while you come to love them, or rather to reverence them. They are so large, so old; they have such marked individuality. The cedars are regal rather than beautiful. Rough and knotted and few in number, at first sight they are a little disappointing; but, like the mountains around them, they become more impressive day by day. These thousand-year-old trees seem to stand aloof from the hurry and bustle of the twentieth century, as though they were absorbed in thoughts of earlier, and perhaps wiser, days. After you have lived for a time beneath their shade, their solemn magnificence begins to quiet your spirit; and when the glorious moonlight floods the mountain and casts black shadows down the deep gorges that drop away to the distant sea, it is easy to behold in the witching light the picture that these ancient trees saw in the long ago. Dark groves of cedars nestle once more In the valleys and sweep over the mountain-tops in great waves of green; a stronger peasantry speaks a different tongue in the fields below that are brighter and the orchards that are heavier with fruit; and from the depths of the moon-painted forest there comes the ring of ten thousand axes that are hewing down the choicest trunks for the Temple of the Lord.

Then the vision fades, and with a sense of personal loss and a regret that is almost anger, you look out again from under the dark branches of the little grove to the bleak, bare mountainside, and the wind in the topmost boughs seems to sing the lament of Zechariah—

"Wail, O fir tree,

For the cedar is fallen,

Because the glorious ones are destroyed:

Wail, O ye oaks of Bashan,

For the strong forest is come down."[9]

The Guardian, the oldest Cedar of Lebanon

The six great columns and the Temple of Bacchus

could sit together. Then there is the Guardian, oldest and largest of all, its great trunk twisted and gnarled by struggles against the storms of ages, the names which famous travelers carved a century ago not yet covered by its slowly growing bark. But the knotted, wrinkled, lightning-scarred giant is crowned by a garland of evergreen, and the venerable tree, which perhaps heard the sound of Hiram's axemen, may still be standing proudly erect when the achievements of our own century are dimmed in the ancient past.

"The Cedars of the Lord"—we understand now why the peasantry of Lebanon call them thus. It has become our own name for them too. Long before we ride downward from their royal solitude to the Great Sea and the great busy world, we have come to think of them as in deed and truth,

"The trees of Jehovah …

The cedars of Lebanon which He hath planted."