Syria, the Land of Lebanon/Chapter 13

CHAPTER XIII

THE GIANT STONES OF BAALBEK

THE most impressive of all the ancient temples of Syria can now be reached by a comfortable railway journey from either Damascus or Beirut. But this way the traveler comes upon the ruins too quickly to appreciate adequately their splendid situation and marvelous size. I shall always be thankful that, on my first visit to Baalbek, I approached it very slowly as I rode from our camp among the cedars of Lebanon. For the longer you look at these temples and the greater the distance from which you behold them, the more fully do you realize that whatever race first built a shrine here chose the spot which, of all their land, had the largest, noblest setting for a sanctuary; and the better also do you understand that these structures had to be made unique in their grandeur because anything less imposing would have seemed paltry in comparison with the surrounding glories of nature.

Where the Bika' is highest and widest and most fertile, on a foothill of Anti-Lebanon which projects far enough to give a commanding outlook in all directions, stands Baalbek, the City of the Sun-God. Far northward Hollow Syria leads to the open wheat-lands of Horns and Hama; at the south it sinks gently to the foot of Hermon. Back of the city are the peaks of the Eastern Mountains, and across the level valley rise the highest summits of Lebanon. It is no wonder that the approaching traveler finds it difficult at first to realize the magnitude of the ruins. Any work of man would be dwarfed by the magnificent heights which look down upon Baalbek. But what an inspiration these same mountains must have been to the unknown architect who conceived the daring grandeur of the Temple of the Sun!

When I viewed the ruins from the summit of the highest mountain of Lebanon, their columns did not seem especially large. Then I remembered that there are few structures whose details can be distinguished at all from a point twenty miles away. After descending many thousand feet through rocky ravines and dry water-courses, we came out on the Bika' and again saw the temples. They now appeared of moderate size and very near. It was hard to believe that a few minutes' canter would not bring us to them and, as we rode across the monotonous level of the valley, it seemed as if each new mile would surely be the last. When I had traveled for an hour straight toward their slender columns and found them apparently as far away as ever, I began to understand that these temples must be of a bigness beyond anything that I had ever seen before.

While we were looking toward Mount Hermon, whose conical summit rose from behind the southern horizon, the hot, shimmering air began to arrange itself in horizontal layers of varying density, and before our wondering eyes there grew a picture of cool and shady comfort. Four or five miles away a grove of date-palms stood beside a beautiful blue lake in which were a number of little islands, each with its cluster of bushes or its group of trees; and, just beyond the islands, the rippling water laved the steep sides of Mount Hermon. It was a cheering sight for the tired traveler. This was no freak of an imagination crazed by privation and exhaustion. Everything was as clear-cut and distinct as were the temples of Baalbek. We knew very well that there was no lake in the Bika' and that Mount Hermon was not within fifty miles of where it seemed to be; yet we agreed upon every detail of the wonderful mirage. We counted the wooded islets; we pointed out to each other the beauty of the shrubbery and the symmetry of the waving palm trees; we remarked upon the sharp reflections of the branches in the clear water. Then, while we looked, the islands began to swim around, the bushes shrank together, the trees shifted their positions, the blue water faded into a misty white, old Hermon receded far into the background—and soon all that was left were two or three dusty palms bowing listlessly over the dry, brown earth in the sizzling heat.

I had always thought of Baalbek as a magnificent ruin in the midst of a wilderness; at best, I expected to find huddled beneath the temples a tiny hamlet like that at Palmyra. But as we came nearer to the spot of green about the columns, it grew larger and larger, and finally opened out into a prosperous looking town of five thousand inhabitants besides, as we discovered later, a garrison of Turkish soldiers and a host of summer visitors. The bazaars were busy and noisy, and the half-dozen hotels were filled with the cream of Syrian society. Gay young prodigals from Beirut clattered recklessly along on blooded mares, or lolled back in rickety barouches, talking French to pretty girls whose silk dresses were so nearly correct that our masculine eyes could not detect just what was the matter with them.

The German archæologists who were then excavating among the ruins told us that the hotel where we had planned to lodge was incorrectly constructed and would surely fall down some day, and advised us to take rooms at the more substantial building where they were dwelling. Here we found one of those typically cosmopolitan companies which add so much variety to life in Syria. Besides the Germans, there was a suave little Turkish gentleman, a very amiable Armenian lady, a radiantly beautiful Hungarian, an English "baroness" who did not explain where she had obtained this obsolete title, and a couple of those innocently daring American maiden-ladies who blunder unprotected through foreign countries whose languages they do not understand, and yet somehow never seem to get into serious trouble. Everybody but the American ladies spoke French, so we had several delightful evenings together. With the Armenian we discussed the recent massacres—when the Turkish gentleman was not by. The Hungarian lady discoursed heatedly upon the thesis that the Magyars are not subjects but allies of the Austrian Empire. The baroness told us thrilling tales of social and political intrigues on three continents, some of which we believed. The Germans interpreted enormous drawings of their excavations, and my traveling companion and I sang negro songs to the accompaniment of a tiny, wheezy melodion.

Baalbek is deservedly popular as a summer resort; for its elevation is nearly four thousand feet and, even in August, there are few uncomfortably warm days. In fact, the city has long borne the reputation of being the coolest in Syria. The Arab geographer Mukadassi, who lived in the tenth century, wrote that "among the sayings of the people it is related how, when men asked of the cold, 'Where shall we find thee?' it was answered, 'In the Belka,'[1] and when they further said, 'But if we meet thee not there?' then the cold answered, 'Verily, in Baalbek is my home.'"

The most attractive features of the city, next to its refreshing climate, are its unusual number of shaded streets and its copious supply of pure, cold water. Both of these are somewhat rare in Syria. In this land of generous orchards, there are very few shade-trees; and during the long, rainless summer the flow of the springs is usually husbanded with great care. In Baalbek, however, the water is allowed to run everywhere in almost reckless abundance. It gushes out of a score of fountains; it drives the mills, waters the gardens and rushes alongside the streets in swift, clear streams. Our own supply for drinking was drawn from one of the springs; but we were told that even the water in the deep roadside gutters was clean and healthful.

On account of the natural advantages of its situation, it is probable that Baalbek has been in existence ever since the time when men first began to build cities. The sub-structures of the acropolis are literally prehistoric, that is, they antedate anything that we know at all certainly about the history of the place. In the Book of Joshua[2] we find three references to "Baal-gad in the valley (Hebrew, Bika') of Lebanon," but the identification of this place with Baalbek is far from certain. The Arab geographers of the twelfth century, who were tremendously impressed by the grandeur of the ruins and the fertility of the surrounding district, believed that the larger temple was built by Solomon, who also had a magnificent palace here, and that the city was given by him as a dowry to Balkis, Queen of Sheba. Benjamin of Tudela, a Spanish rabbi who visited Syria in the year 1163, wrote that when Solomon was laying the heaviest stones, he invoked the assistance of the genii.

It may possibly be that the foundations are even older than the time of Solomon; but there is no historical notice of the city which goes back of the Roman period. Coins of the first century A. D. indicate that it was then a colony of the Empire and was known as Heliopolis, the Greek translation of the Semitic name Baalbek.

During the early centuries of our era Heliopolis became exceedingly prosperous and, indeed, famous. The emperor Antoninus Pius is said to have erected here a temple to Jupiter which was one of the wonders of the world, and coins struck in Syria about 200 A. D., in the reign of Septimius Severus, bear the representations of two temples. During this period the worship of Baal became popular far beyond the borders of Syria, and the Semitic sun-god was identified with the Roman Jupiter. The empress of Severus was daughter of a priest of Baal at Homs, only sixty miles north of Baalbek. When her nephew Varius[3] usurped the throne, he assumed the new imperial title of "High Priest of the Sun-God" and erected a temple to that deity on the Palatine Hill. At Baalbek itself the worship was accompanied by licentious orgies until the conversion of Constantine the Great, who abolished these iniquitous practices, erected a church in the Great Court of the Temple of the Sun, and consecrated a bishop to rule over the still heathen inhabitants of the new see.

Since then, the history of Baalbek has been parallel to that of every other stronghold in Syria, a history of battles and sieges and massacres and a long succession of conquerors with little in common except their cruelty. When the Arabs captured the city in the seventh century, they converted the whole temple area into a fortress whose strategic position, overlooking the Bika' and close to the great caravan routes, enabled it to play an important part in the wars of the Middle Ages. Many a great army has battered at this citadel. Iconoclastic Moslems have done all they could to deface its carvings and statues, earthquake after earthquake has shaken the temples, scores of buildings in the present town have been constructed from materials taken from the acropolis, columns and cornices have been robbed of the iron clasps that held their stones together, and for many years the Great Court was choked with the slowly accumulating debris of a squalid village which lay within its protecting walls.

Yet neither iconoclast nor sapper, artilleryman nor peasant, has been able to destroy the majesty of the temples of Baalbek. The malice of the image-breaker cannot tumble down thousand-ton building-blocks and grows weary in the effort to deface cornices eighty feet above him. Mosques and khans, barracks and castle walls have been built out of this immense quarry of ready-cut stone, yet the supply seems hardly diminished. The cannonballs of the Middle Ages fell back harmless before twenty feet of solid masonry, and only God's earthquake has been able to shake the massive foundations of the Temple of Baal.

The old walls of the acropolis provide many a tempting place for an adventurous clamber. Beside the main gateway at the eastern end you can ascend a winding stairway, half-choked with rubbish; then comes some hard climbing over broken portions of the upper fortifications and a bit of careful stepping around a narrow ledge on the outside of a turret. But it is well worth a little exertion and risk to reach the top of this majestic portal, where you can lie lazily among great piles of broken carvings carvings and watch the long shadows of the setting sun creep over what have been called "the most beautiful mass of ruins that man has ever seen and the like of which he will never behold again."

Our superlative expressions are prostituted to such base uses that it is hard to find words to picture adequately these colossal structures. To say that they are most majestic, gigantic, stupendous, is only to trifle with terms. The mere partition-wall beneath us is nineteen feet thick, a single stone in one of the gate-towers is twenty-five feet long, and the entrance stairway, now half-buried beneath an orchard, is a hundred and fifty feet wide. Everything about us is immense; yet the parts are so nicely proportioned that at first their size does not seem very unusual. The German archaeologists warned me against jumping carelessly from one stone to another. "The distance between them will be greater than you think." You have to revise your ordinary judgments of perspective before you can realize that yonder little alcove in the Great Court is as big as an ordinary church, or can make yourself believe that the outlines of the Temple of the Sun enclose an area as large as that of Westminster Abbey, or can break the habit of thinking condescendingly of the "Smaller Temple"—which is one of the finest Græco-Roman edifices in existence. Suddenly you see the acropolis in its real immensity and beauty, and then you

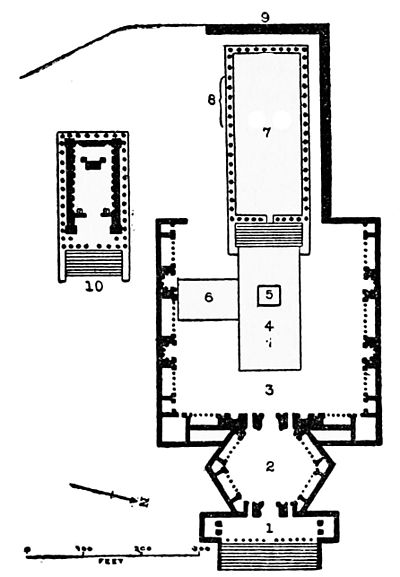

The Acropolis of Baalbek—1, The Propylæa; 2, The Forecourt; 3, The Court of the Altar; 4, The Basilica of Constantine; 5, The Great Altar of the Temple; 6, Byzantine Baths; 7, The Temple of Jupiter-Baal; 8, The Six Standing Columns; 9, The Great Stones in the Foundation Wall; 10, The Temple of Bacchus.

understand how the most scholarly of all Syrian travelers could say that the temples of Baalbek "are like those of Athens in lightness, but far surpass them in vastness; they are vast and massive like those of Thebes, but far excel them in airiness and grace."[4]

From the entrance stairway at the east to the Great Temple at the west, the arrangement is grandly cumulative. Each succeeding architectural feature is larger and more beautiful than that which precedes it. As you view the acropolis from above the portico, your eye is drawn on and on, past the symmetrical forecourt and the great Court of the Altar, under delicately chiseled arches and graceful cornices, through the Triple Gate and the temple portal, up to the culmination of it all—the six tall columns which still rise above the ruins of the Temple of the Sun. No! this is not yet the climax of the glories of Baalbek; for beyond those slender shafts the hoary head of Lebanon, towering far into the sky, at once dwarfs and dignifies, enslaves and ennobles, the puny massiveness of the sanctuary of Baal.

The Great Court, or "Court of the Altar," is littered with sculptured stones—pedestals of statues, inscriptions in Greek and Latin, broken columns, curbs of old wells and fragments of fallen cornices. On each side of the few remains of the Basilica of Constantine are Roman baths, which are carved in a graceful, profuse manner, very like those at Nîmes in southern France.

The sculptors seem to have worked in three shifts. The first were mere stone-cutters who removed surplus material, shaping a hemisphere where a head was to appear in bas-relief, and indicating the rough outlines of leaves and flowers. The second set of workmen carved the design more carefully, leaving it for the third, the master-artists, to give the final touches. In the temple baths we can see traces of the work of all three classes. One part of the carving is finished to the last crinkle of a rose leaf; another is but roughly blocked out by a mere artisan. It seems that the full plan for the courts was never carried to completion. Some think, indeed, that the only portion of the Great Temple itself which was finished was the peristyle.

A little to the southwest of the Court of the Altar stands the Temple of Bacchus. This suffers the fate of great men whose fame is eclipsed by that of their greater brothers. Yet this "Smaller Temple," as it is commonly called, is larger than the Parthenon, and is surpassed in the beauty of its architecture by no other similar edifice outside of Athens. It was originally surrounded by forty-two columns, each fifty-two and a half feet in height. A number of these have been overthrown by earthquakes and cannonballs, but on the north side the peristyle is still nearly perfect. One of the columns on the south side has fallen against the temple, yet, although made up of three drums, the parts are held so firmly together by iron clamps that it has broken several stones of the wall without itself coming to pieces.

Intricate stone-cut tracery runs riot over the double frieze, the fluted half-columns and niches, and the variously shaped panels which form the roof of the peristyle. There are flowers and fruits and leaves, vines and grapes and garlands, men and women, gods and goddesses, satyrs and nymphs, and the youthful god himself, surrounded by laughing bacchantes. Most elaborate of all is the carving around the lofty central portal, which is probably more exquisite in detail than anything else of its kind in existence. The door-posts are forty feet high, yet they are chiseled with such a delicacy that they seem almost as light as a filigree of Damascus silver-work. Upon the under side of the lintel a great eagle holds a staff in its claws, while from its beak droop long garlands of flowers, the ends of which are held by genii.

Of the Temple of Jupiter-Baal, which was the principal structure of the acropolis, only six columns are now standing; but these six can be seen far up and down the Bika'. As you stand beside them and look up, the columns appear of tremendous bulk, as indeed they are; yet their proportions are so elegant that at a little distance they seem almost frail. When you view them from many miles away, they appear as tenuous as the strings of a colossal harp, awaiting the touch of Æolus himself to set them vibrating in tremendous harmony. Now the columns, crossed by the cornice above, resemble a titanic gate ready to swing open to the Garden of the Gods; now they are seen in profile, like a giant finger pointing upward. When the evening glow falls upon them, the stone takes on a yellowish tinge and the slender shafts look like a golden grating which some old master has put between the panels of his daring picture of brazen clouds and dazzling mountaintops. Even the long colonnades of Palmyra lack something of the peculiar grandeur of the six columns of Baalbek, as they stand guard over the ruined Temple of Baal, with nothing to rival their towering grandeur save the eternal peaks of Lebanon.

Yet, though these columns are the most beautiful things in Baalbek, they are not its greatest marvel; for in the foundations of the acropolis are stones so immense that we can only guess at the means employed to quarry and transport and lift into place these huge masses of rock.

Parallel to the north side of the Temple of the Sun is an outer wall ten feet thick and composed of nine stones, each thirty feet long and thirteen feet high; in the west foundation-wall of the acropolis are seven other stones of equal size, not lying upon the ground but set on lower tiers; and just above these is a series of three stones which are probably the largest ever handled by man.

These tremendous three were so renowned in ancient times that the temple above them came to be known as the Trilithon. They are each thirteen feet

The stone in the quarry of Baalbek

The Orontes River at Hama

high, probably ten feet thick, and their lengths are respectively sixty-three, sixty-three and a half, and sixty-four feet. It is hard to realize their true dimensions, however; for these enormous blocks are set into the wall twenty-three feet above the ground, and are fitted together so closely that you can hardly insert the edge of a penknife between them. Look at them as long as you will, you can never fully see their bigness. Yet if only one were taken out of the wall, a space would be left large enough to contain a Pullman sleeping-car. Each stone, though it seems only of fitting size for this noble acropolis, weighs as much as many a coastwise steamer. If it were cut up into building blocks a foot thick, it would provide enough material to face a row of apartment houses two hundred feet long and six stories high. If it were sawn into flag-stones an inch thick, it would make a pavement three feet wide and over six miles in length.

The quarry from which was taken the material for the temples is about three-quarters of a mile from the acropolis. Here lies a still larger stone which, on account of some imperfection, was never completely separated from the mother rock. By this time we have no breath left for exclamations; hyperbole would be impossible; the simple measurements are astounding enough. The Hajr el-Hibla[5] as it is called, is thirteen feet wide, fourteen feet high, seventy-one feet long, and would weigh at least a thousand tons. It does not arouse our wonderment, however, as much as do those other stones, only a little smaller, which were actually finished and built into the wall.

How, indeed, were such huge blocks moved from the quarry to the acropolis? How were they lifted into place and fitted so nicely together? The question has not been answered to our entire satisfaction. We must acknowledge that those old Syrians—if they were Syrians—could perform feats of engineering that would challenge the science of the present day. The most plausible guess is that a long incline was built all the way from the quarry to the temple wall and then, through a prodigal expenditure of time and labor, the blocks were moved slowly up the regular slope, a fraction of an inch at a time, by balancing them back and forth on wooden rollers. But it is almost as easy to believe with the natives that there were giants in those days, and that the great stone which is still in the quarry was being carried along under her arm by a young woman, when she heard her baby cry, and so dropped her burden and left it there to be the wonderment of us puny folk.

- ↑ East of the Jordan, between Jabbok and Arnon rivers.

- ↑ Joshua 11:17, 12:7, 13:5.

- ↑ Varius Avitus Bassanius, who took the name Heliogabalus upon his appointment as high priest of the sun-god, was born at Homs, A. D. 204, usurped the imperial throne at the death of his cousin Caracalla in 218 and, after a brief reign marked chiefly by its infamous debaucheries, was murdered by the Prætorians in 222.

- ↑ Edw. Robinson, Biblical Researches in Palestine, III. 517.

- ↑ Literally, "the stone of the pregnant woman." Bearing in mind the meaning of the popular name, the reader will easily understand just how and why I have modified the frank, Oriental form of the story which follows.