Tensing Exercises

Spalding "Red Cover" Series of

Athletic Handbooks

No. 33R.

TENSING

EXERCISES

BY

EDWARD B. WARMAN, A.M.

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA

PUBLISHED BY

AMERICAN SPORTS PUBLISHING

COMPANY

21 Warren Street, New York

Copyright, 1918

by

American Sports Publishing Company

New York

INTRODUCTORY.

There is good in all systems of Physical Education, but there is more good in some than in others. Being more or less familiar with every system extant, I have no hesitancy in declaring in favor of a system that did more in six years than any other system or combination of systems did in thirty years. That is what this "Tensing" and "Resisting" system of exercises did for me, and I now publish it for the first time—as a system.

It is the most thorough, the most complete, the most satisfactory and the most fascinating of systems.

Notwithstanding all this, you will seriously mistake if you depend solely upon any system of exercises for the purpose of obtaining and retaining health while at the same time you disregard the laws of hygiene.

I have devoted these pages exclusively to my system of exercises, inasmuch as I have elsewhere endeavored to treat, quite fully, the important subjects of Eating, Drinking, Bathing, Breathing, Ventilation, Underwear, Insulation, Color of Clothing, etc., etc.

Assuming that you are interested in the all-around development, I take the liberty of suggesting that you procure my previously published series (covering the foregoing subjects)—six in number, as follows: Nos, 142, 149, 166, 185, 208, 213; only ten cents each.

All of these belong to the popular Spalding's Athletic Library Series, and may be obtained from any agent handling the "Spalding Athletic Goods"; or of any newsdealer, or may be ordered direct from the publishers, the American Sports Publishing Company, New York City, N. Y.

Vigorously yours,

EDWARD B. WARMAN.

A FEW POINTERS.

Tire a muscle (not yourself) if you desire its greatest development. This, however, is not necessary to secure general contour of figure.

Only forty minutes are required to take all the exercises herein given. If you do not need all, do not take all. Of this you must be the judge. Believing, as I do, that every part of the body needs daily exercise, I take all of them daily; all (except the floor exercises) immediately after arising; all of the floor exercises before retiring.

Whatever you do, be it never so little, do it regularly and systematically.

Do not hold the breath while exercising. Contract the muscles as if you were overcoming an actual resistance. When a muscle is brought to its greatest tension, it should be held a moment, then thoroughly relaxed.

To hold your breath when exercising is to let your muscles tear down at a rapid rate. The carbon dioxide accumulates very fast in the muscles and if you shut off the supply of blood or impoverish it, particularly during vigorous exercise, it is surely a tearing down instead of a building up process; whereas, if you breathe continuously and rhythmically, fresh blood flows to the parts exercised. The gasping that follows the too long holding of the breath during exercise is liable to injure the valves of the heart.

Bear in mind that muscles are not made better merely by working them, but by nourishing them; also, by giving them fresh blood upon which to feed regularly.

To extract the maximum amount of work from all the slow, tense exercises (those that have an interval of rest) the muscular contraction at the end must be positive; i. e., when you have done all you can (?), just do a little more, give an extra squeeze, impulse or contraction before relaxing.

Full contraction of a muscle is absolutely necessary to produce the best results; i. e., the greatest possible shortening of which a muscle is susceptible. To illustrate. If a twelve-inch muscle is contracted to the full—say seven inches—then fresh blood, necessary to its nutrition is caused to flow through all its smallest vessels; but this is not the case if the muscle is contracted to only eight inches. The contraction must be the fullest possible, whatever may be the shape of the muscle.

"Accuse not Nature; she hath done her part:

Do thou but thine."

FIG. 1

CORRECT POSITION.

Standing.

See Fig. I.

Correct position means the harmonic poise of the entire body. The chest should be prominent; the hips and abdomen drawn back, the chin drawn in, slightly.

The weight of the body should be neither upon the heels nor too far forward, but about midway between the two extremes. Do not bow back nor bend forward nor allow the chest to sink.

When you have correct standing position you will be able to rise on your toes and descend again to your heels without striking them heavily or bearing your weight thereon. In thus ascending and descending, the body will not sway either backward or forward.

To know what the correct position is, is one thing; to get it, is quite another, but to retain it habitually is the sum total of the "knowing" and the "getting."

FIG. 2

CORRECT POSITION.

Sitting.

See Fig. 2.

When sitting at the desk to write or at the table to eat, one rule holds good: viz., do not have your chair too close to the desk or table. Sit as far back in the chair as you can without your back touching the chair back. Avoid stooping. Incline your body from the hips, not from the waist. Keep your eye (your mental eye) on your backbone. That right; all right. But it is never right (in either a standing or sitting posture) if there is a hump in it.

FIG. 3

CORRECT POSITION.

Walking.

See Fig. 3.

To obtain a graceful carriage of the body—strength and grace combined—it is essential that the head be well poised, the chest prominent (the abdomen, not too much in evidence), the step firm but elastic.

Be unconscious of the legs except as a means of support. Walk, as it were, from the chest. The walls of the chest should be raised and fixed (muscularly), the breathing at the waist (diaphragmatic), the mouth closed.

The athlete should show that he is an athlete at all times and on all occasions; he should show it because he can't help showing it; he should show it by his activity in repose, his clear complexion, his bright eye, his buoyancy and his general manly bearing.

FIG. 4

DIAPHRAGMATIC BREATHING.

Abdominal.

See Fig. 4.

Place the tips of the fingers firmly just below the base of the sternum (breastbone), about over the pit of the stomach. Stand erectly, but do not incline the body backward lest you tense the muscles of the abdomen. Inhale (through the nostrils) slowly but fully, causing a strong outward pressure against the fingers (not below). Check the movement a moment, then slowly expel all the air possible, the fingers following the relaxing muscles.

Should you have any difficulty to get a strong movement of these abdominal muscles, lie on the floor flat upon your back, and place a heavy book or other object directly over the spot on which you pressed the fingers. Raise the object by the breathing. You will thus gain control of the breathing and, at the same time, greatly strengthen the abdominal muscles.

FIG. 5

DIAPHRAGMATIC BREATHING.

Intercostal.

See Fig. 5.

Place the back of the fingers against the ribs and while pressing firmly, inhale slowly and fully, causing a strong outward pressure against the fingers. Check the movement a moment, then slowly expel all the air possible, the fingers following the receding movement.

FIG. 6

DIAPHRAGMATIC BREATHING.

Dorsal

See Fig. 6.

Place the hands to the small of the back, the thumbs pressing on each side of the spinal column. Inhale slowly and fully, causing an outward pressure against the thumbs. Check the movement a moment, then slowly expel all the air possible, the thumbs following the receding movement.

FIG. 7

DIAPHRAGMATIC BREATHING.

Belt.

See Fig. 7.

Draw around you an imaginary, elastic belt. Span as much of the waist as possible. Inhale slowly and fully, exerting an equal pressure front, sides and back. Check the movement a moment, then slowly expel all the air possible, the hands following the relaxing of the waist muscles.

You will observe that this is a combination of the three forms of exercises previously given. After gaining perfect control of the abdominal, intercostal and dorsal breathing, then, in all exercises requiring deep breathing use the latter form—the belt.

ACTIVE AND PASSIVE CHEST.

See Figs. 8 and 9.

By an active chest I mean that the chest should be raised to its highest position muscularly; i. e., independently of the breathing—purely a muscular exercise; the passive chest being a complete relaxing of the muscles.

I am not an advocate of clavicular breathing to the extent of the raising or the clavicle (collar bone). All breathing should begin at the waist (diaphragm) and then extend upward, but without lifting the upper chest.

The mobility of the chest can be obtained and retained by muscular action—active to passive, passive to active, etc., and by exercising the shoulder, back and chest muscles as hereinafter indicated.

FOREARMS AND FINGERS.

See Figs. 10 and 11.

With the arms full length hanging at side, open and shut the fingers alternately. This should be done very slowly and powerfully as if resisting an opposing force.

Extend the fingers and thumbs, in opening the hand, as if some one exerted a strong pressure against each finger and thumb and almost prevented your opening the hand, extending the digitals to the utmost. Relax, retaining position of fingers.

Starting from this point, tense fingers and thumbs, and gradually close the hands against the same resisting force, clenching the fist as tightly as possible before relaxing and repeating.

Ten or more times.

FOREARMS AND FINGERS.

See Figs. 12 and 13.

Extend the arms full length at side, palms down. Grasp, tightly, an imaginary or light dumbbell or rubber grips.

Without lowering the arms, draw the hands as far underneath as possible. This should be done slowly as if resisting an opposing force. Relax. Again tensing the muscles, raise the hands slowly to position and above as far as possible (without raising the arms), resisting the same imaginary opposing force.

Ten or more times.

FIG. 14

NECK.

See Fig. 14.

Imagine that some one is trying to choke you, and you have no other recourse than to tense your neck muscles.

Think strongly, as it were, at the neck and, through the action of your thought, you can swell the neck muscles as if actually overcoming a strong resistance.

Ten or more times.

ABDOMEN, BACK, SHOULDERS, ARMS.

See Figs. 15 and 16.

With the body resting only on the palms of the hands and on the toes, raise and lower the body slowly—without getting your back up.

Push the body up full length of the arms and then lower it until the face nearly touches the floor. Do this very slowly, but do not allow the body to sag in going down nor to curve the other way in going up. From the head to the feet it should remain as rigid as a log.

Ten or more times.

FIG. 17

SIDES, SHOULDERS, ARMS, BACK.

See Fig. 17.

Tense your arms to the utmost—after pushing them out a short distance from the sides of the body—and then bring them toward, but not quite to, the body, checking them in opposition to a strong imaginary force.

This exercise—so difficult to make plain through the medium of the pen—is not only one of the most fascinating, but one that exercises a set of muscles that is rarely, ofherwise, developed.

Twenty-five times.

ABDOMEN, SHOULDERS, CHEST, BACK.

See Figs. 18 and 19.

Raise the hands high above the head as if to touch the ceiling, bend slightly backward to get an impulse for the swinging forward. Keep the arms extended and as you sway forward touch the hands to the floor (or try to) without bending the knees. Then bring the body up to position and as far back as you can without undue straining, swinging the arms up and back of the head.

Caution—Always bend the knees when going backward.

Fifty times; back and forth, counting one.

ABDOMEN, SHOULDERS, CHEST, HIPS.

See Figs. 20 and 21.

As you raise the right arm—fully extended—and swing it up over your head, bend your body as far to the left as possible (straight to the left) keeping both feet solidly upon the floor.

Then swing the body as far as possible to the right, raising the left arm and lowering the right; keeping both feet solidly upon the floor. Tense the arms.

Twenty-five times; right and left counting one.

ABDOMEN AND HIPS.

Liver Squeezer.

See Figs. 22 and 23.

Stand perfectly erect. Twist the body slowly to the right and slowly to the left. Do not move the feet. This may be taken with the arms akimbo until accustomed to the movement, then the arms may be tensed and swung right and left as though striking at some one on each side as right or left is used.

Fifteen times; right and left counting one.

Note.—The three exercises just preceding are known throughout the land as my "pet exercises." There are no series of movements better adapted for obtaining and retaining the suppleness of the waist muscles and for reducing or preventing excessive flesh on the hips and abdomen. To be effectual, however, they must be taken the full quota of times and with daily regularity.

ABDOMEN.

See Figs. 24 and 25.

Lie flat upon the back, the arms stretched above the head and in line with the body. Draw up both knees, clasp them with the hands, press them firmly against the abdomen, exhaling as you press. Then inhale deeply as you extend the arms and legs in opposite directions—back to position.

Twenty-five times.

UPPER ARMS.

See Figs. 26 and 27.

Extend the arms horizontally. Tense the arms, close your hands half way (thumb and fingers opposing each other). Pull both hands straight for the shoulders; pull slowly as if resisting an opposing force. Make the muscular contraction very positive at the end of every movement. Relax. Push the hands back to position slowly as if resisting an opposing force. Extend arms to the utmost. Relax.

Do not allow the elbows to lower in either movement.

Seven times.

UPPER ARMS.

See Figs. 28 and 29.

Extend the arms horizontally. Hands half closed, palms down. Tense the arms. Think of the arms as a strong steel rod. Rotate the arms as far to the right and as far to the left as possible—very slowly, and as if resisting an opposing force.

In order to retain the arms in position, imagine each hand turning, as it were, in a hole in the wall.

Seven times.

UPPER ARMS.

See Figs. 30 and 31.

Bow the legs. Arms at side, close to the body. Hands half-closed, palms forward. Tense the arms. Lift both hands, slowly, as if lifting a very heavy weight in each hand. Close the arms with a positive muscular contraction. Relax. Tense hands and arms again and lower them, slowly, as if resisting an opposing force.

Seven times.

CALF AND FOREARM.

See Fig. 32.

Standing in the correct position—the weight of the hody over the center of the feet—raise the heels as far as possible from the floor and lower them again to position without swaying the body forward and backward. Rise slowly, and settle very lightly on the heels.

As you rise, tense your entire body and imagine a very powerful person holding his hands on your shoulders. This will necessitate very slow movement with great resistance. As you descend, the same force is used to overcome an imaginary resistance—as if powerful hands were placed under your arms.

Seven times.

Fifty times, when taking the movements more rapidly—without the resistance. These, for the sake of suppleness, should follow the resisting exercise. At the same time close and open the hands as in exercises Nos. 10 and 11.

THIGHS.

See Fig. 33.

The squatting exercise. Settle the body as nearly as possible on the heels as they rise from the floor—the knees well apart. Then rise to position.

Tense your entire body as you slowly descend against an imaginary resisting force. Do the same as you rise. The slower and the greater force exerted the more rapid and complete the development.

Seven times.

Twenty-five times rapidly, without resistance. There is no better exercise to give elasticity to one's step.

THIGHS AND KNEES.

See Fig. 34.

Resting the left hand, lightly, on back of chair (for balance) and weight of body on left foot, KICK vigorously forward and out with right leg, and recover quickly.

The same with the left leg—the right hand on back of chair and the right leg bearing the weight of the body.

Take this mildly at first so as to avoid any undue strain of tendon or ligament.

Fifty times with each foot.

HIPS, THIGHS, KNEES.

See Fig. 35.

Resting the weight on the left foot, the left hand on the hip or chair, extend the right arm to its fullest extent, palm of hand toward the floor, the arm on a level with the shoulder (or higher). Kick high enough with the right foot to touch the toes to the palm of the hand—without lowering the hand.

Then, resting the weight on the right foot, repeat the movement with the left foot.

Ten times—each foot.

ABDOMEN.

See Fig. 36.

Lie flat upon the back. Tense the arms alongside the body, but not resting them on the floor. Tense the legs. Lift them and lower them slowly, without bending the knees. Keep the legs together. Do not allow the head to rise from the floor.

Seven times—up and down—without the legs or heels resting upon the floor until the seventh time.

Caution.—Do not hold the breath. Inhale as the legs ascend; exhale as they descend; or, as is my rule in general, let the breathing take care of itself, providing you do not restrict it.

CHEST AND SHOULDERS.

See Figs. 37 and 38.

Bow the legs. Extend arms to the side. Tense arms and halfclosed hands. Bring them to the front on a line with the shoulders; then back to position without lowering the arms. This should be done rapidly and very vigorously.

Fifteen times, without stopping.

Caution. — Do not hold the breath.

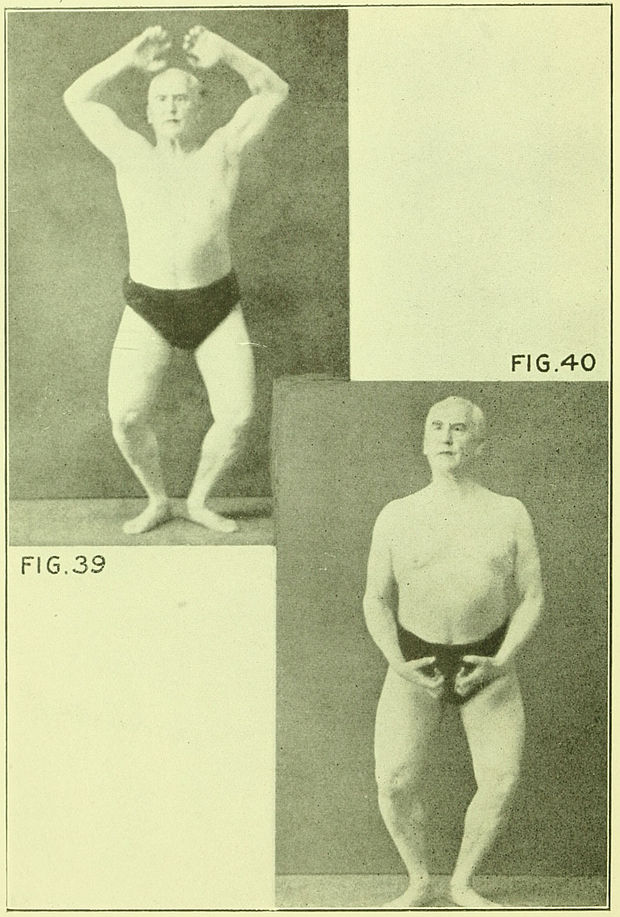

CHEST AND SHOULDERS.

See Figs. 39 and 40.

Bow the legs. Bring the half-closed hands to the front near the body, palms up, the fingers toward each other, the arms not fully extended but bent at elbow, forming a sort of half circle. Tense the arms and hands very strongly and swing them out and up at the sides, almost above the head, completing the circle without opening the arms. Rapidly and vigorously.

Fifteen times, without stopping.

Caution.—Do not hold the breath.

CHEST AND SHOULDERS.

See Figs. 41 and 42.

Bow the legs. Bring the half-closed hands toward the body, thumbs almost touching each other, elbows extending somewhat sidewise. Tense the arms and hands and swing them up in front and above the head without changing the relative position of the hands and arms. Up and back to position rapidly and vigorously.

Fifteen times without stopping.

Caution.—Do not hold the breath.

CHEST AND SHOULDERS.

See Fig. 43.

Bow the legs. Tense the arms and half-closed hands, extending one arm up and forward, the other down and back. Swing the arms, alternately, down and back, up and front, keeping perfect time. Keep the arms perfectly straight and at the side, not allowing the body to twist. Keep the tension of the arms throughout.

Twenty-five times without stopping.

Caution.—Do not hold the breath.

NECK AND CHEST.

See Figs. 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 and 49.

Have the head well poised. Bend it as far forward as possible—chin to chest, and then as far backward. Do not move the body.

Have the head well poised. Endeavor to lay the ear upon the shoulder—first right, then left. Do not move the body from side to side nor allow the shoulders to lift. Keep the eyes toward the ceiling (about 45 degrees) in order to keep the correct position of the head.

Have the head well poised. Turn it to the right and left alternately—without moving the body.

If you desire muscular development of the neck, tense the muscles as if someone was placing the hand against the head to prevent the various movements.

If you desire flexibility take the movements without tensing or resisting.

Fifteen times forward and back.

Ten times side to side.

Five times, turning or twisting right and left.

ABDOMEN.

See Figs. 30 and 31.

Lie flat upon the back. Extend the arms full length above the head resting them upon the floor. Tense the arms and legs. Raise them both simultaneously, arms and legs toward each other above the body. The legs kept together and unbent. Do not allow the head to rise from the floor.

Seven times—up and down—without the legs or heels resting upon the floor until the seventh time.

Caution.— Do not hold the breath. Inhale as the legs and arms ascend, and exhale as they descend; or, as is my usual custom, let the breathing take care of itself, providing it is not restricted.

ABDOMEN.

See Figs. 52 and 53.

Lie flat upon the back. Fold the arms easily across the chest. Rise to a sitting posture without allowing the heels to lift from the floor or the knees to rise. Lower the body as slowly as you rise. Keep the legs flat upon the floor.

If your abdominal muscles are not sufficiently strong, at first, to do this without a jerk or without lifting the legs, place the feet under the dresser, couch or some other object until the muscular contraction is sufficient of itself to raise and lower the body slowly.

As this movement has an interval of rest at the end of the sitting and lying posture, I would suggest that you inhale before each movement and exhale at the close, i.e., inhale before rising, exhale after rising; inhale before returning, exhale after returning.

Seven times, up and down.

ARMS AND SHOULDERS.

See Figs. 54, 55 and 56.

(1) Lock the thumbs together. Extend the arms downward close to the body. Pull vigorously and steadily for a moment or two. Then lock the forefingers and do likewise; then the middle fingers; then the third (or ring) fingers; then the little fingers; then grip the ends of all the fingers of one hand with the ends of all the fingers of the other hand.

(2) Repeat the foregoing with the hands higher up—the forearms at right angles with the upper arms.

(3) Repeat the foregoing with the hands higher up—about opposite the neck.

ARMS AND SHOULDERS.

See Figs. 57 and 58.

(4) Repeat the exercise on previous page, with the hands back of the head.

(5) Repeat the foregoing by starting at the last position and ending at the first by a steady attempt to pull apart from start to finish. During the entire passage the arms should be fully extended after raising them above the head and moving forward.

Avoid bending backward; rather incline the body forward.

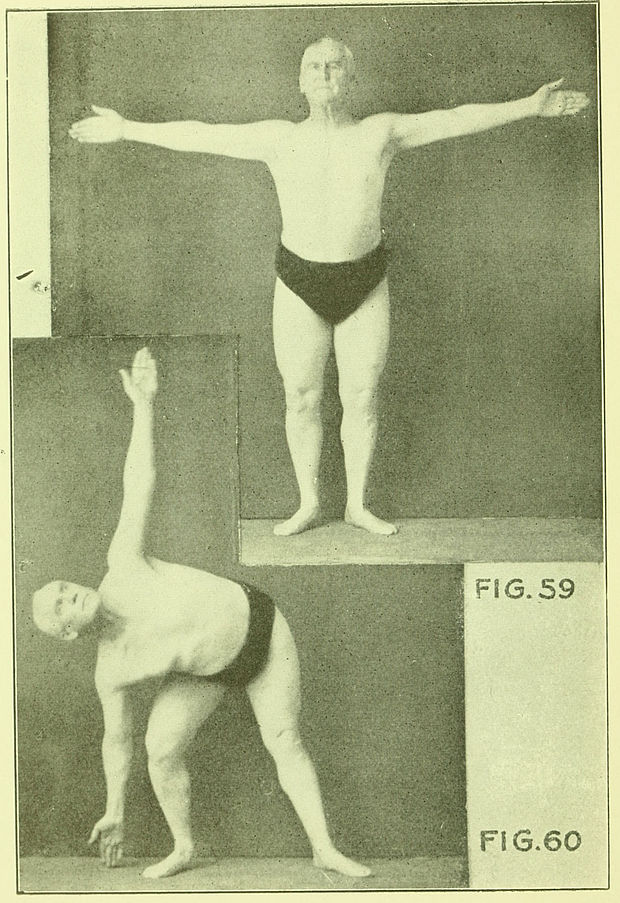

ANOTHER LIVER-SQUEEZER.

See Figs. 59 and 60.

Stand erect, arms outstretched, feet 20 inches apart, abdomen drawn back.

Bend to the left, flexing the left knee, but keeping the right leg straight. Touch the floor with the left hand, by the side of the foot.

Recover, make a momentary pause, and reverse the movement by flexing the right knee, keeping the left leg straight and touching the floor with the right hand, by the side of the foot.

Keep the abdomen well drawn in, especially when returning to position.

Ten times side to side.

A REST FOR BODY AND BRAIN.

See Figs. 61 and 62.

Place the hands back of the head. Interlace the fingers. Lean slightly backward and move the body sidewise—right and left—stretching the body to the utmost. Relax the mind as you stretch the body.

This need not be taken at any specified time nor any number of times, but when brain or body needs a recreative exercise.

CALF, SHIN, ANKLE, FOREARM.

See Figs. 63 and 64.

Sit. Extend the legs straight in front, high enough for the feet to escape the floor. Extend the arms down by your side. Tense the arms and legs. Close and open the hands as in exercises Nos. 10 and 11. As you close the hands with a firm grip, draw the ball of the foot firmly toward your body (heels pressed forward). As you open the hands and extend the fingers, press the ball of the foot firmly forward (the heels toward the body). Do not raise or lower the legs.

Twenty-five times.

ABDOMEN, SIDES, BACK, SHOULDERS.

See Figs. 65 and 66.

Sit on the fioor, body erect. Hold a rod or stick in the hands; knuckles up.

Work the body right and left, as when paddling a canoe with a single oar. Carry each movement to the extreme turning point, the face following the movements of the hands. Endeavor to look directly to the rear, forcing the leading hand (the lower one) as far as possible. Do not allow the legs to move. This is an excellent exercise for the liver and kidneys.

Twenty-five times.

ABDOMEN AND THIGHS.

See Fig. 67.

Lie on the right side, supporting the head with the hand, the other hand on the hip.

Raise the left leg as far as possible. Keep the leg perfectly straight as you tense it and carry it as far forward and as far backward as possible. Point the foot downward. Endeavor to move the leg horizontally.

Turn over and repeat the exercise with the right leg.

Twenty-five times; each leg.

A CHAPTER FROM A BUSY LIFE.

Written for Health Culture, 151 West Twenty-third Street, New York.

My Dear Mr. Turner:

About once a year I get around to make my bow to the readers of Health Culture, to let them know that I am neither dead nor sleepeth, but, instead, as the years go by, my enthusiasm for perfect health and manly strength keeps ever apace with the times.

As figures do not lie (except in election returns), I trust that the following comparative table will prove to your many readers that the fool doctor of Chicago was entirely off his base when he declared that a man could not and should not attempt to develop, physically, after reaching thirty-five years of age. This statement is about as absurd as that of Dr. Osler, who claims that a man's usefulness is over at forty and that he should be chloroformed at sixty, and laid on the shelf.

Last Saturday (April 29) I celebrated my birthday anniversary (fifty-eight) in my usual way, by riding as many miles on my wheel (before breakfast) as I am years old—or, I should say, years young. You see, I am within two years of the chloroform period, but it would take a mighty good man to lay me on the shelf, or even on my back.

While I am interested in the physical education of the young of both sexes, I am especially interested in the betterment of the physical condition of those persons having reached or having passed the foretieth or fiftieth milestone—an age at which they are liable to let up in their active physical life. I desire to assure them that letting up in daily exercise means letting down in health.

Of course, the average man or woman of middle age does not possess the vigor of youth; however, I think it possible (as in my own case). Yet, as the mind has a most wonderful effect upon the body, I would suggest that the thought of health and strength should be constantly held, and then appropriate exercise taken to conform with that thought; then add to this, right living.

If I were asked as to the indications of health I would answer:

- Correct position of the body.

- Correct carriage of the body.

- A light and elastic step.

- A clear complexion.

- A bright eye.

- A sweet breath.

- An odorless body.

These, all of these, may be obtained and then retained until long after passing three-score-and-ten.

If I were asked how to get and how to keep health (health is wholeness, so there is no modification or qualification of that term; no good health nor poor health nor tolerable health—just health), I would call attention to seven more important factors, viz.:

- We eat and drink to make blood.

- We should exercise to circulate it,

- We should breathe deeply to oxygenate (purify) it. Then keep normally and naturally active the four eliminating agents:

- The bowels.

- The skin.

- The lungs.

- The kidneys.

To do this we should eat wholesome food (eating no more than the system requires), bathe daily (the temperature of the bath being suited more to the needs of the body than to the whims of the mind), exercise regularly (not spasmodically), and be temperate in all things.

Any one can theorize, but to live up to one's theory is quite another question. I am willing to be measured by the same standard wherewith I measure; therefore to encourage any that "may have come tardy off" I submit the following figures, which plainly indicate that I take my own medicine:

AN INTERESTING AND ENCOURAGING RECORD.

Age Does Not seem to Have Its Limitations. Began in 1868—Still at it in 1905. Note the Record of the Past Few Years.

| Warman | 1895 | 1896 | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 |

| Age … | 48 yrs | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 |

| Weight … | 202 lbs | 197 | 193 | 186½ | 187 | 190 | 187 | 167 | 176 | 180 | 180 |

| Waist … | 42 in. | 42 | 42 | 42 | 41 | 40 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| Hips … | 44 in. | 44 | 43 | 42 | 42 | 41½ | 41 | 40 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| Forearm … | 11 in. | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11¼ | 11½ | 11½ | 11¾ | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Upper arm … | 12¼ in. | 12¼ | 12¼ | 12¼ | 12½ | 12¾ | 13½ | 14 | 14½ | 14½ | 14½ |

| Neck … | 15 in. | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15¼ | 15½ | 15¾ | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Calf … | 15 in. | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15¼ | 15½ | 15¾ | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Thigh … | 23 in. | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23½ | 23½ | 23¾ | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24½ |

| Chest (normal) … | 43 in. | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43½ | 43¾ | 44½ | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Chest (contracted) … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | 38¼ | 38 | 38 | 37 |

| Depth of chest (Normal) … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.3 |

| Seventh Rib (expanded) … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | 40 | 41 | 41 | 41 |

| Seventh Rib (contracted) … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | 36 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

I have no record of measurements previous to 1895. I remember, however, that my weight in 1871 (during my "sparring bouts" with my old chum, Charlie Nolting in the old Fourth Street gymnasium, in Cincinnati, Ohio.) was then but 145 pounds.

From 1895 to 1898 the measurements remained about the same, but in the latter part of 1898 (having passed my fifty-first birthday anniversary) I formulated my system of tense exercises (double contraction), which I now take daily.

Note the increase in the measurements of the forearm, upper arm, neck, calf, thigh and chest; the decrease in waist and hip measurements, and the great decrease in weight since 1895.

It will be observed that in 1902 I dropped down to 167 pounds (the lowest in twenty years). This was due to a change of diet—but only in one respect, viz.: the complete cutting out of meat for a period of three months. This occurred during our never-to-be-forgotten sojourn in that most charming city, country and climate—Victoria, B. C.

During that period I made no other change in my habits, but rode my wheel, as usual, in the early morning hours (covering 1,039 miles), and ate, as usual, but two meals a day.

Not being a vegetarian, I did not partake of those vegetables that are a substitute for meat (beans, peas, lentils), except occasionally the former. This was not because I do not believe in them, but because I do not like them. In the place of meat I ate eggs and cheese, daily. Notwithstanding the fact that I ate cereals with an abundance of sugar and cream, more potatoes in the three months than I would usually eat in a year, cheese (of which I am exceedingly fond); these and other fattening foods, I lost in weight instead of gaining. Physiologically considered, this may seem to be almost paradoxical; but not so. In the ordinary run of life this would make one very fleshy (adipose tissue), but my exercise was so vigorous that instead of this food forming fat cells it was consumed as heat for the necessary muscular energy.

The result as regards health? I was, have since been, am now, and always shall be well—perfectly well every minute of every day. Yes. I have gone back to the flesh-pots of Egypt, but I am not an extremist. When I want meat I eat it. Nature makes out my bill of fare and when she calls for meat it is forthcoming; sometimes once a day, for two or three days in succession; sometimes only three or four times a month. Therein I know I am not a slave to appetite.

It is not so much what you eat as how you eat, not how much nor how little you eat. Out of my thirty-seven years' experience it took me twenty years to learn this little, simple, yet fundamental principle; to learn, also, that physical training, per se, is but half the battle; that health, strength and longevity depend equally, as much upon right living; that every man should be a law, unto himself, but he must understand the law. I have no patience with the extremists or the faddists only insomuch as they get people out of a rut and cause them to think for themselves.

I trust that this little message may be the means of arousing to action some casual reader of H. C. (the regular readers "need no spur to prick the sides of their intent"). Then, in conclusion, I say—Begin now!

"How wise we are when the chance has gone

And a backward glance we cast;

We know just the thing we should have done

When the time to do is past."

Vigorously yours,

Edward B. Warman.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1930.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1931, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 93 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse