The Boy Travellers in Australasia/Chapter 19

CHAPTER XIX.

BEFORE returning to the coast our friends had an opportunity to visit a native encampment and see a corroboree. The reader naturally asks what a corroboree is; we will see presently.

Arrangements were made by their host, and early one morning the party was off for the native encampment, which was nearly thirty miles away. A tent and provisions had been sent along the previous evening, so that the travellers had nothing to carry on their horses beyond a lunch, which they ate in a shepherd's hut at one of the out stations. Early in the afternoon they reached their tent, which had been pitched on the bank of a brook about half a mile from the village they intended to visit.

Taking an early dinner, they set out on foot for the encampment, being guided by a native who had come to escort them. We will let Frank tell the story of the entertainment.

"The village was merely a collection of huts of bark, open at one side, and forming a shelter against the wind, though it would have been hardly equal to keeping out a severe storm. To construct these huts the bark had been stripped from several trees in the vicinity. Fires were burning in front of most of the huts, and care was taken that they did not extend to the trees, and thus get a start through the forest.

"There was an odor of singed wool and burning meat, but no food was in sight. The blacks are supposed to live upon kangaroo meat as their principal viand, but a good many cattle and sheep disappear whenever a tribe of them is in the neighborhood of the herds and flocks. In addition to kangaroo, they eat the meat of the wallaby, opossum, wombat, native bear, and other animals, and are fond of eels and any kind of fish that come to their hands, or rather to their nets and spears. Emus, ducks, turkeys—in fact, pretty nearly everything that lives and moves, including ants and their eggs, grubs, earth-worms, moths, beetles, and other insects—are welcome additions to the aboriginal larder. All the fruits of trees and bushes, together with many roots and edible grasses and other plants, are included in their bill of fare.

"There were twenty or more dirty and repulsive men and women in the village, some squatted or seated around the fires, and others walking or standing carelessly in the immediate vicinity. A dozen thin and vicious-looking dogs growled at us as we approached, but were speedily silenced by their owners. These dogs were simply the native dingoes, either born in captivity or caught when very young and domesticated. They are poorly fed, and the squatters say they can generally distinguish a wild dog from one belonging to the blacks, by the latter being thin and the former in good condition.

"More women than men were visible, and it was explained that the men who were to take part in the corroboree were away making their preparations. The corroboree is a dance which was formerly quite common among the tribes, but has latterly gone a good deal out of fashion. At present it is not often given, except when, as in the present instance, strangers are willing to pay something in order to see it. Our host had arranged it for us, and the camping party that preceded us with the pack-horses had brought the stipulated amount of cloth, sugar, and other things that were to constitute the payment for the entertainment.

"We tried to make friends with some of the children, but they were decidedly shy, and we soon gave it up. In a little while the men who were to dance came out from the forest, and as they did so the women formed in a semicircle at one side of the cleared space in the middle of the encampment; and some of the men brought fresh supplies of wood, and heaped it on the central fire. The women sat on the ground, and each had an opossum rug stretched tightly across her knees and forming a sort of drum.

"The dancers assembled in the centre near the fire; they wore only their opossum rugs around the loins, and the exposed parts of their bodies were streaked with paint in the most fantastic manner imaginable.

A CORROBOREE.

SOMETHING FOR BREAKFAST.and kept time by beating with their hands upon the opossum-skins.

"Suddenly the leader struck the two sticks together, and the dancers formed in line. When the line was completed he struck them again, in unison with the chant and the time beaten on the drums. The dancers regulated their movements by the music, throwing themselves into all sorts of positions, moving to the right or the left, advancing or retreating, standing straight in line, circling around each other, and in a general way forming figures not altogether unlike those of civilized dancers in other lands.

"As the dance went on, the leader quickened the time; the chant and drumming quickened likewise, and so did the exertions of the performers. They grew hot, and perspired at every pore; faster and faster went the music; faster and faster were the movements of the bodies, till it seemed as though they would drop from exhaustion.

"Suddenly the men, as if by a prearranged plan, jumped higher than ever into the air, and as they did so each gave a sort of shrill shout. The drumming and chanting ceased immediately, and the men fled to rest in the shelter of the bushes. There they remained for perhaps a quarter of an hour, and then they returned and resumed the dance. The second part was much like the first, except that some of the figures were different; the whole performance showed that it was the result of practice, as the time was well kept and all the movements were based upon a system of no insignificant character. At the end the leader gave two heavy strokes with his sticks, the men retreated, the women followed them, and the dance was at an end.

"We are told that the natives have various dances, and in this particular they resemble the savage tribes of most other lands. They have their war-dances before and after fights, dances for the time when the youths are 'made men'—i.e., when they attain their majority, and are no longer to be classed as boys—dances in which only the women take part, dances in which the movements of the kangaroo and other animals are imitated, and a variety of religious and mystical dances to which Europeans are never admitted. In some dances an entire tribe—men, women, and children—participate; in others only the men, or only the women; and there are certain dances in which several tribes may join. All the people of the tribe are instructed in these dances, and the rules concerning them must be observed with most scrupulous care.

"Nearly all the dances are performed at night, and quite often by the light of the moon added to that of the fire. I have heard some amusing descriptions of dances where there was a mimic battle between white men and aboriginals, the fictitious white men biting their cartridges and going through the motions of loading and firing a gun with great exactness. There was a representation of a herd of cattle feeding, of some of the animals being speared by the blacks, who then went through

NEAR THE CAMP.the motions of skinning and cutting up the slaughtered beasts. The movements of the kangaroo, emu, and other animals were imitated, and so were those of the pig, the bear, and the opossum.

"At the end of the dance we went to our camp accompanied by the natives, who were to receive payment for the performance. After their departure we sat around the fire for a while listening to corrorobee stories, and then retired to our blankets and to sleep. Our dreams were filled with pictures of yelling and gyrating natives, and altogether neither Fred nor myself felt much refreshed when we rose in the morning; but we were all right in an hour or so, and shall always remember our adventure among the Australian blacks.

"We heard some curious stories about their customs, particularly of the way the men get their wives. Marriage as understood among civilized people is unknown among the Australian blacks. Fathers dispose of their daughters as they would of sheep or cattle; and if the father be dead, the right falls to the nearest male relative. A man with a daughter of marriageable age arranges to dispose of her, and when the price is agreed upon she is called forward and told that her husband wants her. She may never have seen him before, or seen him only to detest him; if she cries and protests, the father exercises his authority by prodding her with a spear or striking her with a club, and he often winds up by seizing her by the hair and dragging her to the hut of the man who has bought her. If she attempts to run away she is clubbed into obedience, and sometimes her father spears her through the leg or foot, so that she cannot run.

AN AUSTRALIAN COURTSHIP.

"Among some of the tribes brothers exchange their sisters with other men, so that a marriage is generally a double affair. There is no ceremony, as we understand it, any more than in a horse-trade with us.

"If a man has no sister, he steals a wife from another tribe than his own; he lies in wait in the neighborhood of the other tribe, and when a young woman passes near him he rushes out and knocks her down with a waddy, or club. Then he drags her to his hut and pounds her into submission. Such a proceeding is perfectly proper, though it almost invariably leads to a fight between the two tribes, no matter how friendly they may have been before the occurrence. It is the duty of the woman's tribe to avenge her abduction, and that of the man's to protect the newly wedded couple.

"The ceremonies for celebrating the coming of age of a young man vary a good deal among the tribes, but in none of them is the performance a pleasing one for the subject thereof. In one tribe he is shut up in a tent for a whole month, and nearly starved; in another he is shaved, painted with mud and pigments, and compelled to sit in a pool of dirty water for a whole day, while the rest of the tribe pelt him with mud; in another he has two of his front teeth knocked out; and in another the young beard on his chin is plucked out by the roots. In every case pain is inflicted, so that the valor of the youth can be tested; and he is expected to endure everything without flinching.

THE NIGHT ALARM.

"During the night we had an alarm which roused us from sleep, and for a few moments it looked as though we were to have serious business. There was a yell in the forest near us, and as we sprang out of our blankets and went to the front of the tent, we saw a crowd of natives in war-paint brandishing their spears and waddies, and acting as though they intended to attack us. Some of them were hideously painted, and altogether the spectacle was not a pleasing one. After a few demonstrations they retired, and our host told us it was a part of our entertainment, to show how a night attack was made by the aboriginals.

"The mimic attack was quite sufficient for our purposes, and we were quite willing not to pass through the experience of a real one. We were told that had the attack been actual, the first warning of it would have been the hurling of spears. Very often it happens that a camping party of white men has no knowledge that natives are within many miles of them until the spears begin dropping in their midst. Our host was once in a party of this sort; they were eight in all; five of them were killed or wounded by the spears; but the remaining three with their rifles and revolvers beat back the assailants, and thus saved their lives."

Our friends returned to the station without further adventure, and a few days later were once more in Sydney, preparing to leave for Melbourne. Up to the last moment of their stay they were busily occupied with the attentions of the numerous acquaintances they had made, so much so that they had barely time to write up their journals and preserve a record of what they had seen and heard.

But there was one attention which was as unexpected as it was interesting, though it could hardly be said to have been bestowed by an inhabitant of the city. It was a visit from a "brickfielder," and is thus described by Fred:

"Mention has been made already of the tendency of an Australian to speak exultingly of the climate of his own city or section, and to disparage that of other localities. All parts of the country suffer from the hot winds of the interior, but the inhabitants of each place declare that it is worse anywhere else than with them. Be that as it may, our first experience of the hot wind here in Sydney is quite bad enough, and if Melbourne or Adelaide can surpass it we pity them.

"They call this wind a 'brickfielder,' probably because it brings a vast quantity of dust such as might be blown from a field where bricks are made or brick-dust has been thickly strewn; and this was what we saw and felt:

"There was a period of calm and ominous silence, and we observed that the sky was changing from blue to a sort of fiery tinge. Puffs of heated air came now and then, like blasts from a furnace; they grew in force and frequency, and in an hour or so became a steady wind with increasing force. It was hot and dry and scorching, and we seemed to be withering under its effects. 'It's a brickfielder, sure enough,' said a friend, and he cautioned us to get back to our hotel as soon as we could. We took his advice, and went there.

RECEPTION OF A BRICKFIELDER.

"In a little while there was a driving volume of dark clouds like a London fog; the wind increased almost to a gale, and then came the dust. It was not a fine, impalpable sand, like that brought to Cairo by the khamseen in April, but a perceptible and gritty dust that sifted into every crevice and cranny, blinded our eyes, filled our ears, and made its way inside our clothing, till we could feel that it was all over our skins.

Nothing is sacred to it, and it invades the most stately mansions as well as the humblest cottages. The air was filled with dust gathered up from the streets, in addition to what the wind brought from the interior; the dustiest and most disagreeable March day of New York was the perfection of mildness compared to it.

"Windows and doors were closed, and it is the rule to keep them so as long as a brickfielder lasts. The hot gale will make its way inside if it can find the least opening, and then the entire house and all its contents will be thickly sprinkled with dust. The heat was intolerable, but there was no help for it, as an open door or window would only bring more heat and the dust in addition. We looked out of the windows, but the dust-cloud was so thick that we couldn't see across the street. A few luckless wayfarers were clinging to posts or struggling

A BRICKFIELDER PUTTING IN ITS WORK.to keep their feet, and those who were trying to go against the wind made very slow progress.

"The brickfielder lasted all day and far into the night, and then it suddenly stopped. With its cessation there was a heavy fall of rain, which converted the dust into mud and made pedestrianism anything but comfortable. They tell us that these winds sometimes last two or three days, or even longer; they are always followed by rain and a cool wind from the south, and never was cool wind more acceptable than at such a time. Nobody can predict when the wind will come, whether in a day, a week, or a month; and when it does come everybody prepares to stay in-doors, if he can possibly do so, and wait till it is over. Every man, woman, and child has a dust-cloak or dust-coat to be worn when necessity compels going out-of-doors in a brickfielder.

"One gentleman says these winds prefer to put in their appearance on Sunday morning, just as the congregations are assembling in church. The dates of large picnic parties are also favorite times for their appearance, and when they come the picnic ceases to be a delight. He says that some years ago, in one of the Australian cities, arrangements had been made for a grand banquet out-of-doors, the finest that had ever been known in the colony. The date had long been fixed and extensive arrangements made, invited guests came from afar, the best speakers of the antipodes were present, and all was going finely, when suddenly, just as the early courses of the banquet had been served, a brickfielder came, and the scene was as disorderly as a political meeting in one of the lower wards of New York. The feast came to a sudden end and not a speaker opened his mouth, lest it might be filled with dust.

"One swallow may not make a summer, but one brickfielder is enough for a whole year."

Consulting the railway time-table, Doctor Bronson found that the express train for Melbourne left at 5.15 p.m., and ran through in nineteen hours, thus making the greater part of its journey in the night. As our friends wished to see as much of the country as possible during their tour through Australia, they decided to take a slower train at 9 a.m., which would bring them to Goulburn, one hundred and thirty-four miles, at 4 p.m. Another train at 10.35 the following morning would reach the frontier at Albury, three hundred and eighty-six miles from Sydney, at eight o'clock in the evening. In this way they would get a good view of the country, and be able to say far more about its features than if whizzed through on an express train at night.

BUILDING A RAILWAY ON THE PLAINS.

The first railway in the colony of New South Wales was projected in 1846, and within two years the surveys for the line to Goulburn were completed. Ground was broken in July, 1850, the first turf being turned by the Hon. Mrs. Keith Stewart, in the presence of her father. Governor Fitzroy, and a large assemblage of people. The first railway-line in the colony, from Sydney to Paramatta, was opened in 1855.

The engineering difficulties and the high rate of interest upon loans retarded the work of railway building, so that in twenty years after the opening of the first line only four hundred and six miles had been completed; but in more recent times the enterprise has been rapidly pushed, the mountains having been passed, and the construction upon the great plains of the interior being comparatively easy. In September, 1886, no less than 1831 miles of railway were in operation in New South Wales, and the Colonial Parliament had authorized 1590 miles in addition, of which a part is now under construction.

The railways of New South Wales are divided into the Southern, Western, and Northern systems. The Southern stretches from Sydney to Albury, on the frontier of Victoria, three hundred and eighty-six miles; at Junee the South-western line branches from the Southern, and runs to Hay, four hundred and fifty-four miles from Sydney, on the Murrumbidgee River, and one of the most important towns in the Riverina district. The Western line runs in the direction indicated by its name, and terminates at Bourke, on the Darling River, five hundred and three miles from Sydney. These are the longest railway-lines now in operation in any part of Australia, though not equal to some that are projected in Queensland and South Australia. The Northern line extends to the frontier of Queensland, as already described.

In round figures, Australia has at present about ten thousand miles of railway in operation, with another ten thousand miles—and perhaps more—in contemplation. The completed lines have cost not less than two hundred millions of dollars, and there are about thirty thousand miles of telegraph in working order.

The up-country journey of our friends, in which they took part in a kangaroo hunt and witnessed a corroboree, was made over the Western line. "We have rarely seen finer engineering work on a railway anywhere else in the world than on this line," said Frank in his journal. "It reminds us of the Brenner line over the Alps, the Central Pacific in the Sierra Nevada mountains, and the ride from Colombo to Kandy, in Ceylon. It was an uninterrupted succession of magnificent views of mountain scenery, with deep gorges and snowy water-falls at frequent intervals. We advise those who may follow us to note particularly the Katoomba and Wentworth Falls and Govett's Leap; and if they have an interest in engineering, they will be much attracted by the Lapstone Hill and Lithgow Valley Zigzags, where the railway climbs the steep sides of the mountains. There is a fine bridge over the Nepean River at Penrith, and a tunnel, called the Clarence, three thousand seven hundred feet above sea-level, and five hundred and thirty–eight yards in length."

There is also some fine engineering on the Southern line; and for a long time, when the railway was first proposed, many doubters predicted that it would never be able to pass the Blue Mountains to the plains beyond. The longest tunnel in Australia—five hundred and seventy-two yards—is near Picton, on the Southern line; and the zigzags, bridges, cuts, and fillings are well calculated to excite the admiration of the professional railway man. As for the scenery, it fully justifies the praises which Australians bestow upon it, and the ride over the Blue Mountains is one that everybody who visits the country should take in the daytime.

ZIGZAG RAILWAY IN THE BLUE MOUNTAINS.

The engineers of this line claim to have succeeded in solving a problem which has been pronounced impossible by many experienced men, and has been tried elsewhere occasionally, and always with disastrous results—that of having two trains pass each other on a single-track railway. It is done in this way: At the end of each zigzag there is a piece of level track sufficiently long to hold two trains. The engineer of a descending train sees an ascending one on the zigzag below; he runs his train out to the end of a level, and there waits until the ascending one has entered the same level, reversed its course, and gone on its way upward. One of the railway managers said to Doctor Bronson. "There isn't any double track here at all, and yet, you see, two trains can pass each other without the least difficulty. The ends of our zigzags serve as switches, that's all."

"You have no idea what a salubrious region this is," said one of the passengers to whom they had been introduced by a friend who came to see them off. "The air is wonderfully bracing, so much so that it is a common saying, 'Nobody ever dies in the Blue Mountains unless he is killed by accident or blown away.' Many people live to more than a hundred years old; there is an authentic account of a man who celebrated his one hundred and tenth birthday six months before he died, and another who was cut off by intemperate habits when he was only one hundred and one. This man used to speak of a neighbor who lived to be one hundred and eight years old and hadn't an unsound tooth in his head, when he was killed by the kick of a vicious horse."

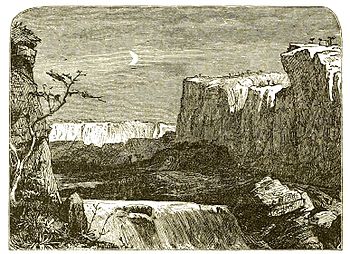

THE BLUE MOUNTAINS.

Frank and Fred were at once seized with a desire to visit Mount Kosciusko, but were restrained by the Doctor, who did not share their enthusiasm for mountain-climbing. So the youths contented themselves with a distant view of the snowy tops of the high peaks of the range, and allowed Mount Kosciusko to rest undisturbed. The country is wild and picturesque, but the facilities for travel are not extensive, and only those travellers who are accustomed to fatigue should undertake the journey. The starting-point for the excursion is the little town of Tumberumba, from which the mountains are about forty miles away. A coach runs between Tumberumba and Calcairn, seventy-four miles, the nearest point on the railway, and the town is said to be pleasantly situated at an elevation of two thousand feet above the sea.

ON THE HEAD WATERS OF THE MURRAY RIVER.

The Murray River, which is sometimes called the Hume in the upper part of its course, takes its rise at the foot of Mount Kosciusko and its companion mountains. The scenery is quite Alpine in all its characteristics, and well justifies the name which has been applied to this part of the great chain. Deep gorges and precipitous cliffs enclose the head streams of the Murray, and the forest extends far up the sides of the mountains wherever there is sufficient soil for trees to find a place to grow. Lower down there are considerable areas of open or cleared country that have proved well adapted to agriculture. Wheat and oats are profitably grown in the vicinity of Tumberumba; and in some parts of the Albury district, in which Tumberumba is situated, tobacco is an extensive crop. (See Frontispiece.)

At Goulburn, where they halted for the night, as previously arranged, our friends found a well-built city of about eight thousand inhabitants, and owing its prosperity to the large amount of inland trade which it controls. Frank and Fred asked for the gold-mines of Goulburn, but asked in vain; they were told that there were no gold-fields in the immediate vicinity, and that the city depended upon its commercial position and the agricultural advantages of the surrounding region. They were invited to visit some lime-burning establishments, and learned that there were extensive quarries of limestone in the neighborhood, with promising indications of silver, copper, and other metals, which as yet are hardly developed.

In the evening the party witnessed a theatrical performance by a strolling company, which was making the rounds of the interior towns of Australia in the same way that American companies go "on the road" during the dramatic season. The acting was good, and the company included several players who were not unknown in New York and other American cities.

The youths had already noted the fact that Australia is a favorite resort of members of the dramatic profession of England and the United States; a considerable number of the men and women well known to the foot-lights of English-speaking countries have at one time or another appeared on the boards of Melbourne and Sydney. Australians are fond of the drama, and there are few cities in the world that can be counted on for a more liberal patronage of good plays and good players, in proportion to their population, than the principal cities of the great southern continent.

From one of the books in his possession Frank drew the following interesting bit of theatrical history:

GALLERY OF A THEATRE DURING A PERFORMANCE.

"The first theatrical representation ever given in Australia was at Sydney, in 1796. The play was 'The Ranger,' performed by a company of amateurs, all of whom were convicts. The manager was also a convict. An admission fee of one shilling was demanded, and the Governor and his staff were graciously invited to free seats. Coin being scarce in the colony, a shilling's worth of flour or rum was accepted in lieu of money. The convict who played Filch recited the prologue, and was probably its author. It ran as follows:

From distant lands, o'er wide-spread seas we come,

But not with much eclat or beat of drum.

True patriots all, for, be it understood,

We left our country for our country's good!

No private views disgraced our generous zeal;

What urged our travels was our country's weal.

And none can doubt but that our emigration

Has proved most useful to the British nation.

He who to midnight ladders is no stranger,

You'll own will make an admirable Ranger;

To seek Macheath we have not far to roam,

And sure in Filch I shall be quite at home.

Here light and easy Columbines are found,

And well-trained Harlequins with us abound;

From durance vile our precious selves to keep

We've often had to make a flying leap;

To a black face have sometimes owed escape,

And Hounslow Heath has proved the worth of crape.

But how, you ask, can we e'er hope to soar

Above these scenes, and rise to tragic lore?

For oft, alas! we've forced th' unwilling tear.

And petrified the heart with real fear.

Macbeth a harvest of applause will reap,

For some of us, I fear, have murdered sleep.

His Lady, too, with grace and ease will talk—

Her blushes hiding 'neath a mine of chalk.

Sometimes, indeed, so various is our art,

An actor may improve and mend his part.

"Give me a horse!" bawls Richard, like a drone;

We'll show a man who'd help himself to one.

Grant us your favors, put us to the test;

To gain your smiles we'll do our very best;

And, without dread of future turnkey Lockits,

Thus, in an honest way, still pick your pockets.'"

The principal theatres of Melbourne, Sydney, and Adelaide will compare favorably with those of any other city on the globe, and there is hardly a town of any consequence at all that does not possess a minor theatre or a hall where entertainments are given occasionally. During the days of the gold rushes the mining regions proved more remunerative to the strolling actors who visited them than to the majority of the men who were digging for the precious metal.

The theatres of those days were often the rudest structures imaginable, and not infrequently performances were given in tents, and sometimes in enclosures that were open to the sun and rain. It is said that a performance of "Hamlet" was once given on an open-air stage in a pouring rain. Ophelia wore a water-proof cloak, and in the last scene in which she appeared she carried an umbrella. Polonius, being an old man, was permitted to wear an India-rubber coat; but Hamlet's youth did not permit such a protection from the weather, and when the play ended he bore a close resemblance to the survivor of an inundation of the Ohio valley, or a man rescued from a shipwreck on the Atlantic coast.

Beyond Goulbourn the railway carried our friends through the district of Riverina, famous for its pastoral and agricultural attractions. At Albury they crossed the Murray River and entered the colony of Victoria; a change of gauge rendered a change of train necessary, and Fred remarked that it seemed like crossing a frontier in Europe, the resemblance being increased by the presence of the custom-house officials, who seek to prevent the admission of foreign goods into Victoria until they have paid the duties assessed by law.

SCENE IN THE RIVERINA.

As before stated, Victoria has a protective tariff, while New South Wales is a free-trade colony. Consequently, Victoria is obliged to guard her frontier to prevent smuggling, and the work of doing so effectively is by no means inexpensive. But she derives a large revenue from the duty on imports, and the statesmen and others who favor a protective tariff can demonstrate by argument and illustration that it is the principal cause of the prosperity of the colony. There is, of course, a goodly number of free-traders in the colony, and the war between free-traders and protectionists is as vigorous and unrelenting as in the United States or England.

The federation of all the Australian colonies, and their union under a single government, on the same general plan as that which was adopted for the British-American provinces, has been for some time under discussion; doubtless it might have been accomplished before this had it not been for the opposition of New South Wales, which holds aloof from the movement mainly on account of the tariff question. Federation will probably come before long; many Australians say it will be a step in the direction of independence, and they argue that a country so far away from England can hardly be expected to retain its allegiance to the mother-country forever, in view of its growing power and population, its diversity of interests, and the perils to which it would be subject in case of a European war in which England should be concerned.

The railway from Melbourne reached Wodonga, opposite Albury, in 1873, but the line from Sydney was not completed till 1881. From that time till 1884 there was a break of three miles which passengers traversed by coach or on foot; in the year last named the connection was completed by the construction of an iron bridge over the Murray, and the closing of the gap with tracks adapted to the gauges of both the colonies. There are now commodious stations on both sides of the river. The New South Wales trains cross the river to Wodonga, while those from Victoria cross it to Albury.

It was evening when the party arrived at the frontier, and as soon as the formalities of the custom-house were over, the Doctor and his young companions went to a hotel near the station. The custom-house was not rigorous, as none of their baggage was opened, the officials being contented with the declaration that they had nothing dutiable in their possession. Next morning the youths were up early to have a look at the great river of Australia; they were somewhat disappointed with the Murray, their fancies having made the river much larger than it proved to be. Compared with the Mississippi, the Hudson, the Rhine, or the Thames, it was insignificant, but it was nevertheless a river navigable from Albury to the ocean, one thousand eight hundred miles away.

A steamboat lay at the bank of the river a short distance below the railway-bridge; it was not much of a boat in the way of luxury, but was well adapted to the work for which it was intended, and had a barge fastened behind it by a strong tow-rope. Fred learned that there were several boats engaged in the navigation of the Murray and its tributaries, but they were unable to run at all seasons of the year. In ordinary stages of water boats can reach Albury, but there are certain periods of the year when they cannot do so.

Some boys were sitting on the bank farther down the river, engaged in fishing with pole and line. Frank and Fred made their acquaintance, and examined the fish they had taken; the oldest of the boys, evidently much more intelligent than his companions, enlightened the strangers as to the piscatorial possessions of Australia.

STEAMBOAT ON THE MURRAY RIVER.

FISH-HATCHING BOXES ON A SMALL STREAM.

"That is the 'Murray cod,' or 'cod-perch,'" said he, as he pointed to one of the results of the morning's work.

"What a splendid fish!" Fred exclaimed.

"What?—that!" said the Australian youth, with an air of contempt. "That's only a little one, and doesn't weigh more'n two pounds."

"How large do these fish grow?" queried Frank.

"Oh! we catch 'em weighing thirty or forty pounds," was the reply. "We bait with tree-frogs, and have to use strong lines, or they'd get away from us."

"They're pretty good eating," he continued, "but not so good as bream and trout; the trout were brought here from your country, and we're getting 'em all through the rivers of Australia, so folks tell me. They sent us the eggs, and the fish were hatched out here; and several kinds of European and American fishes have been introduced that way. We've a good many kinds of perch; how many I don't know, but the best is the golden perch of the Murray and the rivers running into it. We've got a black-fish, as we call him; he's black outside, but his flesh is white as snow, and he's splendid for eating.

"If you want to go trout-fishing, you can do so twenty miles from Melbourne and find all you want; they've been trying to raise salmon in Australia, but the rivers are too warm for 'em. Sometimes we read in the newspapers about somebody's catching a salmon, but it never amounts to much."

Frank presented his informant with a shilling, partly in return for his information and partly to secure the fish, which he carried to the hotel and requested that it be cooked for breakfast. It was cooked accordingly, and when, accompanied by the Doctor, the youths sat down to their repast, the fish was pronounced a toothsome morsel.

Soon after ten o'clock they were in the railway-train for Melbourne. They traversed a varied country, passing through a rich pastoral and agricultural region, through widely extended wheat-fields, and in sight of numerous flocks of sheep and herds of cattle, through stretches of forest more or less luxuriant, over plains and among hills, along winding valleys, and occasionally in sight of the mountains which lie between the Dividing Range and some portions of the coast. In due time the crest of the range was passed, and the train descended gently to Melbourne and deposited the travellers safe and sound at the railway terminus.

IMMIGRANT'S CAMP IN THE FOOT-HILLS OF THE RANGE.