The Boy Travellers in Australasia/Chapter 20

CHAPTER XX.

FRANK and Fred were impatient to see Melbourne, the city of which they had heard so much, and whose praises are loudly chanted by every resident of the colony of Victoria. As they rode from the railway-station to their hotel they could hardly believe that they were in a city where half a century ago there was little more than a clearing in the forest on the banks of the Yarra.

Yet so it was. On June 2, 1835, John Batman ascended the Yarra and Salt-water rivers, and made a bargain with the native chiefs of the locality to purchase a large area of ground, more than one thousand two hundred square miles, for which he paid a few shirts and blankets, some sugar, flour, and other trifles—probably not a hundred dollars' worth altogether. The Government afterwards set aside his purchase, but paid to Batman and his partners the sum of £7000 for the relinquishment of their claim.

Batman returned immediately to Tasmania to procure a fresh supply of provisions, and near the end of August, 1835, during his absence, another adventurer, John Fawkner, landed on the banks of the Yarra from the schooner Enterprise, and made his camp in the forest on the bank of the stream. He brought five men, two horses, two pigs, one cat, and three kangaroo-dogs; and this was the colony that founded the present city of Melbourne. Fawkner may be fairly considered the founder of Melbourne, as the permanent occupation of the site dates

THE FOUNDING OF MELBOURNE, AUGUST, 1835.

from the day he landed from his schooner. But Batman's part of the affair should not be forgotten; he returned in the following April, and settled on what is now a part of the city. As might be expected, there was a bitter quarrel between Batman and Fawkner as long as both survived, and it was continued by their descendants.

The inhabitants of Melbourne have duly honored Batman by erecting in the old cemetery of that city an appropriate monument to his memory. He died in 1839, before the city had grown to much importance though it was giving good promise for the future. At the time of Batman's death there were four hundred and fifty houses, seventy shops, and three thousand inhabitants in Melbourne, and the first ship had sailed for London with a cargo of four hundred bales of wool.

Frank and Fred learned all this before taking their first stroll along the streets of Melbourne on the morning after their arrival. They also learned that the city took its name in honor of Lord Melbourne, who was then Premier of Great Britain. Frank suggested that perhaps Shakespeare had Melbourne in mind as the "bourne whence no traveller returns," since a great many deaths occurred there during the gold rush. Fred reproved his cousin for using this antiquated "chestnut," and the topic was indefinitely postponed.

PUBLIC LIBRARY, MELBOURNE.

"Three hundred and sixty thousand people in a city which was first settled in 1835!" said Fred. "Chicago and San Francisco must look sharp for their laurels."

"They may look, but they won't find them," replied Frank.

"Are you not mistaken?" queried his cousin. "Did not each of them have as many inhabitants as Melbourne within fifty years after its settlement?"

"We will see," was the reply. "Chicago was practically founded in 1816, when Fort Dearborn, which had been destroyed in 1812, was rebuilt. In 1870, fifty-four years later, it had, according to the census, 298,997 inhabitants.

MELBOURNE POST-OFFICE.

"San Francisco was begun in 1770, when the Mission of San Francisco de Asis, more commonly called the Mission Dolores, was established there; but some people claim that the city was not really founded until 1835, when the village of Yerba Buena was built, and to please them we'll start from that date, which is the year in which Melbourne was founded. By the census of 1880, forty-five years from its foundation, it had 233,959 inhabitants, and at its fiftieth anniversary was doubtless considerably behind Melbourne. But Chicago has gone ahead of both of the other cities in question, as it contained more than half a million people in 1880, and was still growing as fast as the extensions on the prairie would permit. Perhaps in time it will cover the whole State of Illinois."

"Melbourne, Chicago, and San Francisco are the marvels of the world in their growth," responded Fred, "and they've no reason to be jealous of one another." Frank echoed this opinion, and then the figures of populations were dropped from discussion.

GOVERNMENT HOUSE, MELBOURNE.

Their walk took them along Collins Street, which is the Broadway or the Regent Street of the city; they traversed its entire length from west to east, and then turned their attention to Bourke Street, which runs parallel to Collins Street. To enumerate all the fine buildings they saw in their promenade would make a list altogether too tedious for anything less than a guide-book. As they took no notes of what they saw, it is safe to say that neither of the youths could at this moment write a connected account of the sights of the morning.

"If we had been skeptical about the wealth and prosperity of Melbourne," wrote Fred in his journal, "all our doubts were removed by what we saw during our first tour through the city. One after another magnificent piles of buildings came before us, the banks and other private edifices rivalling the public ones for extent and solidity. The highest structure in Melbourne is known as Robb's Buildings, and was built by a wealthy speculator, on the same general plan as the Mills, Field, and similar buildings in New York. There are many banks, office buildings, stores, warehouses, and other private edifices that would do honor to London, Paris, or New York; and the same is the case with the Post-office, Houses of Parliament, Law Courts, Public Library, National Gallery, Government House, Ormond College, and other public structures.

"We turned down Swanston Street in the direction of the river, the Yarra, or, to speak more properly, the Yarra-Yarra, as it was originally known, though few now call it by the double name. Anybody who comes here expecting a great river will be disappointed, as the Yarra isn't much of a stream on which to build a city like Melbourne. It answers well enough for people to row upon with pleasure-boats and for occasionally drowning somebody, but is altogether too small and shallow for large vessels. Steamers and sailing-craft drawing not more than sixteen feet can come up to the city, but large vessels must stop at Sandridge, or Port Melbourne, two and a half miles away. The Yarra supplies water for the Botanical Gardens, but not for the city generally.

COLLINS STREET IN 1870.

"We reached the river at Prince's Bridge, where a fine viaduct of three arches replaces the former one of a single arch. There are several bridges across the Yarra, which separates Melbourne proper from South Melbourne and other suburbs, and we were told that new bridges are under consideration, and will be built as the necessity for them becomes more pressing. A great deal of money has been expended in deepening and straightening the river, and it is certainly vastly improved upon the stream which Batman and Fawkner ascended in 1835, when they made the settlements from which Melbourne has grown. Since 1877 the river has been deepened three feet, and the minimum low-water depth is said to be fourteen feet six inches at spring-tides.

PUBLIC OFFICES AND TREASURY GARDENS.

"Street-cars, or 'trams,' some drawn by horses and others by cables, run in every direction; and there are omnibuses, cabs, and other conveyances; so that one can go pretty nearly anywhere he chooses for a small amount of money. Some of the omnibuses remind us of the new ones in Paris, as they have three horses abreast, and dash along in fine style. Hansom and other cabs are numerous, and the fares are about a third more than in London; this is a great change from the days of the gold rush, when the most ordinary carriage could not be hired for less than £3 a day, and very often the drivers obtained twice or three times that amount. We have been told of a gold-digger just down from the mines of whom £12 was demanded one day for an afternoon's drive; he handed the driver a ten-pound note, and told him he would have to be satisfied with that—and he was.

TOWN-HALL, MELBOURNE.

"We went into three or four arcades, which form pleasant lounging and shopping places, like the famous 'passages' of Paris and the arcades of London. One of them is called the 'Book Arcade,' and is principally devoted to the sale of books; and if we may judge by the number of volumes we saw there, the people of Melbourne are liberal patrons of literature. No matter what the taste of a person might be in books, whether he desired a work of fiction or a treatise on science, a volume of travels or an exposition of Hindoo philosophy, he could be accommodated without delay. They have a public library here containing nearly one hundred and fifty thousand volumes, all of which can be read without charge.

"When we got back to the hotel and met the Doctor, it was time to sit down to breakfast. He had already received two invitations to dinner from gentlemen to whom he brought letters; they had heard of our arrival, and knowing we had been hospitably received in Sydney, were determined that we should be initiated at once into the courtesies of Melbourne, and start off with a favorable impression of the place.

VIEW FROM SOUTH MELBOURNE, 1868.

"On many of the streets trees have been planted, and they add much to the attractions of the city. The water-supply of Melbourne comes from an artificial lake nineteen miles from the city, and is brought in by the Yan Yean Water-works, which are not altogether unlike the Croton works of New York or the Cochituate of Boston. Water seems to be abundant in all the houses, and we are told that there are more bath-tubs in Melbourne than in any other city of its size in the world.

"We can't begin to name all the churches we have seen in our rides and walks along the streets. Suffice it to say there are no finer modern churches anywhere than here, and the inhabitants of Melbourne have shown great liberality in their contributions for building these religious edifices. There is no State Church in the colony, but the Church of England is the fashionable one, and has a greater number of adherents than any other church.

PART OF MELBOURNE IN 1838.

"In their order, and omitting the smaller figures, there were by the last census of the colony 311,000 Episcopalians, 203,000 Catholics, 132,000 Presbyterians, 108,000 Methodists, 20,000 Independents, or Congregationalists, 20,000 Baptists, and 11,000 Lutherans and German Protestants. On the first of January, 1886, there were 2150 churches and chapels in Victoria, and about the same number of public buildings and dwellings used for public worship, or more than 4000 in all.

"While we were riding about the city we asked our host whence came the names of the streets.

"'The principal ones commemorate men who were connected with the early history of the colony,' was his reply. 'Collins Street is named for Colonel Collins, who established a convict settlement on the shores of Port Phillip Bay in 1803, but soon gave it up and removed the settlement to Tasmania. Bourke Street is named after the governor of New South Wales in 1836; Flinders Street after Captain Flinders, of whose explorations you are doubtless aware; Lonsdale Street after Captain Lonsdale, who was in command here about that time; and Swanston Street after one of Batman's companions. King, Queen, William, and Elizabeth Streets are tokens of our loyalty to the royal family of Great Britain, the same as are the streets of like names in Sydney and Brisbane.'

"I should have said, in speaking of the streets, that between every two wide streets there are narrow ones which were originally intended as back entrances, and were known by the prefix of 'little.' Thus we have Little Collins Street between Collins and Bourke Streets; Little Bourke Street between Bourke and Latrobe, and so on through the list. Most of these 'little' streets have become known as lanes, and are spoken of as Collins Lane, Bourke Lane, etc. Bourke Lane is largely occupied by Chinese, and Flinders Lane, between Flinders and Collins Streets, is generally known as 'The Lane,' especially among the dealers in clothing throughout Australia, as it is the peculiar haunt of the importers of wearing apparel, or 'soft goods.'

"Elizabeth Street runs in the valley between the two principal hills on which the city is built, and divides it into East and West, just as Fifth Avenue divides the numbered streets of New York. As Melbourne is on the other side of the world from New York, it is quite in the nature of things that the custom of designating the portions of a street should be the reverse of ours. In New York we say 'East Fourteenth Street,' or 'West Twenty-third Street.' Here they say 'Collins Street East,' or 'Bourke Street West,' according as the designated locality is east or west from Elizabeth Street.

"We returned to the hotel in good season to dress for dinner," continued Fred, "and at the appointed time went to the place where we were to dine. It was several miles out of town, and our journey thither was by railway, our host sending a carriage to meet us at the station. Melbourne resembles London in having a net-work of suburban railways, and resembles it further in having a great rush of people to the city in the morning, and out of it in the afternoon. Ordinarily the facilities of travel are fairly equal to the demand, but if a heavy shower of rain falls about 6 p.m., the supply of vehicles is insufficient.

A SUBURBAN RESIDENCE.

"The house of our host is well built and well furnished, and has plenty of ground surrounding it for garden, lawn, and shrubbery. English trees grow in the grounds. Much of the furniture came from the old country, but the portion of it that was made in Melbourne is by no means inferior to the imported part. Prosperous people in Melbourne know how to live well, and some of the wealthier inhabitants spend a great deal of money on the support of their establishments. We dined as well as we could have dined in London or New York, the local luxuries of those cities that were wanting here being fully atoned for by the products of the colony.

"It was late in the evening when we got back to our hotel in the city, after listening to stories of colonial life in general, and of life in Melbourne in particular, until our heads were nearly giddy with what had been poured into them. Anthony Trollope intimates that the Melbournites are given to 'blowing' about the wonders of their city, and he excuses them on the ground that they have something worth 'blowing' about. If we were to make any remark on this subject, it would be to agree with him on both points. But as one hears the same kind of talk in Chicago, St. Louis, San Francisco, and other American cities, and also in the other colonial centres of Australasia, we have ceased to wonder at it, and set it down as a matter of course."

In the next day or two our friends visited some of the suburbs of Melbourne, including Notham, Carlton, Fitzroy, Collingwood, and Brunswick on the north, and Richmond, Prahran, Windsor, Malvern, and Caulfield on the south. Frank noted that some of these suburbs were prosperous and well populated, while others were much less so, and seemed to base a goodly part of their hopes on the future. There is a great deal of speculation in suburban land, just as in the neighborhood of all large cities the world over; fortunes have been made in suburban speculation, and still larger fortunes hoped for but not yet realized.

Melbourne was originally laid out in half-acre lots, but nearly all of them have long since been divided and subdivided. One of the few that have not been divided, but are held by the families of the purchasers, is in a good part of Collins Street. The colonist who bought it paid £20 for the lot in 1837; it is now worth £100,000, and since the time of the original purchase the holders have received at least £100,000 in rents. One million dollars in fifty years from an investment of one hundred dollars may be considered a fairly good return for one's money.

Doctor Bronson and his nephews were not neglectful of the harbor of Melbourne any more than they had been of Sydney Cove when at the capital of New South Wales. There are trains at short intervals from Melbourne to Sandridge (Port Melbourne), and cars and omnibuses every fifteen minutes. The fare is threepence, or six cents. This is a great reduction from the days of the gold rush in 1851, when the omnibus charge between Sandridge and Melbourne was two shillings and sixpence (sixty-two and one-half cents) for each passenger, and a carriage for four persons cost from five to twenty dollars for the single trip.

Mr. Manson, who was so attentive to our friends in Sydney, was equally well acquainted with Melbourne; he called upon them shortly after their arrival in the latter city, and proposed to accompany them in their visit to the port. His offer was at once accepted. During the ride to Sandridge the conversation turned upon the days of the gold rush, and the incidents that long since passed into history.

"It was before I came to Australia," said he, "so that I cannot speak from personal knowledge; but I have heard the stories from so many old residents that I have no doubt of their correctness. The expense of getting goods from Sandridge to Melbourne, three miles, was often as much as to bring them from London to the harbor. William Howitt tells, in his 'Two Years in Victoria,' that the cost of carrying his baggage from the ship to his lodgings in Melbourne was more than that of bringing them the previous thirteen thousand miles, including what he paid for conveyance from his house to the London docks.

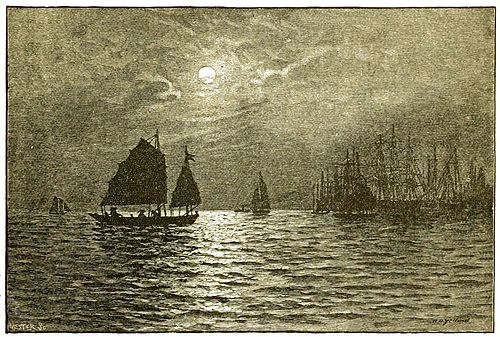

HARBOR SCENE IN THE MOONLIGHT.

"When a ship arrived with passengers, the charge for taking them from the anchorage to the beach was three shillings, and then came the omnibus charge already mentioned. If a man was alone, the boatmen charged him ten or perhaps twenty shillings; and if a person was obliged to go out to a ship, and they knew his journey was important, they would charge any price they pleased. A gentleman having occasion to visit a ship that was about to sail, and manifesting some anxiety to do so, was obliged to pay £12, or sixty dollars.

"After goods were landed they were loaded into carts for transportation to Melbourne. A clerk looked at a load, and then said, glibly, 'These things will be £3;' and if anybody demurred at the price, the gate-keeper was ordered not to let the cart pass out of the yard till the sum demanded was paid. People grumbled and denounced the charges as outrageous, but they generally paid them and went on.

"In the city the same high scale of prices prevailed. In the shops the prices were about three hundred per cent, above the cost of goods. Lodgings were in great demand; the meanest kind of an unfurnished room was worth ten dollars a week, and two poorly furnished ones were from twenty to thirty dollars a week. Hotel-keepers turned their stables into sleeping-places, and a man paid five shillings a night for a third of a horse's stall, good straw, a blanket, and a rug. One landlord had seventy of these five-shilling lodgers in his stable nightly, in addition to the occupants of the rooms in the legitimate portion of his house."

BOARDING-HOUSE OF 1851.

"They did so," was the reply, "and so many tents were spread on the waste ground outside the city that the place became known as Canvas Town. The Government charged five shillings weekly for the privilege of putting up tents on this waste ground, or at the rate of sixty dollars a year. Of course all were anxious to get away as soon as possible, but they were often detained three or four weeks, or even longer, waiting to obtain their goods from the ships."

"Was there much security for life and property in those days?" Frank asked.

"According to all accounts there was a great deal of disorder," Mr. Manson responded. "There were many runaway convicts here from Tasmania and New South Wales, together with other bad characters. Robberies along the road were very common. One Saturday afternoon in broad daylight four fellows armed with guns and pistols stopped some twenty or more people, one after the other, tied them up to trees, and robbed them, on the road from Melbourne to St. Kilda. The bushrangers carried on their performances up to the very edge of Melbourne, and sometimes they rode through the streets and out again before they could be stopped.

"The coolest piece of robbery was performed in the harbor one night. A ship was to sail for England at daylight, and she had several thousand ounces of gold on board. About midnight a party of eight or ten went out in a boat pretending to have business on board, and were admitted without suspicion. Their real business was to plunder the ship, and they succeeded; they 'stuck up' the officers and crew, bound them hand and foot, loaded the gold into their boat, and escaped. No alarm was given until some one went on board the next morning, as all the officers and crew had been gagged and locked in below.

A GOOD LOCATION FOR BUSINESS.The robbers got clean away; nothing was ever learned about them, but it was suspected that they were ex-convicts from Tasmania."

The carriage had by this time brought our friends to Sandridge, and they alighted at the head of one of the piers. There are two piers at Sandridge (to use its former name in place of its more modern appellation of Port Melbourne), These piers run far out into the bay, and ships of almost any tonnage may lie alongside to discharge or receive cargoes. One is known as the town pier, and the other as the railway pier; on the railway pier trains of cars may load or discharge at the side of the ships, and thus effect a great saving in the handling of freight.

It was a busy scene from one end of the pier to the other, and as the strangers walked about they were obliged to be cautious lest they were LOADING A SHIP FROM A LIGHTER.

Some of the steamships have their docks at Williamstown, which is on the other side of Hobson's Bay, directly opposite Sandridge, and connected with Melbourne by railway. The business of Williamstown, like that of Sandridge, is mostly connected with the shipping; a steam ferry carried our friends across the bay, and they spent an hour or two in Williamstown, the time being principally devoted to an inspection of the ship-building yards and the graving dock, which has accommodations for the largest ships engaged in the Australian trade.

Hobson's Bay may be called the enlarging of the Yarra at its mouth, or the narrowing of Port Phillip Bay at its head. But by whatever description it is known it is an excellent harbor for Melbourne, as it has good anchorage and abundance of space for the ships that congregate there. Port Phillip Bay is about thirty-five miles long and the same in width; its entrance is nearly two miles across, and, like Sydney harbor, it has space for all the navies of the civilized world. No doubt the Melbourne people would not object to such a visitation, provided it were peaceful, for the same reason that the Sydneyite gave to Frank and Fred, "that it would be a good thing for business."

On their return from Williamstown to Sandridge the party drove to St. Kilda, the Coney Island of Melbourne, and a great resort for those who are fond of salt-water bathing. Farther down the bay is Brighton Beach, a familiar name whether the visitor be from New York or London, and if he looks further he will find other names that will not be altogether strange. All around the bay there are pleasure resorts, private residences, business establishments, factories, and other evidences that the region has long since been reclaimed from the possession of the savage and become the permanent home of the white man.

Fred observed that there were fences far out in the water enclosing areas where bathers were splashing and, to all appearances, having a good time. He immediately asked what was the use of the fences.

"They are for protection against sharks," replied Mr. Manson, "which are abundant in these waters and all along the Australian coast. You have doubtless heard of them at other points."

The youth remembered the sharks at Queensland and New South Wales, and the stories he had heard about them. He remarked that if the creatures were as bad as they were farther north, he should not venture into the water at St. Kilda until satisfied that the fence was thoroughly shark-proof.

The carriage was sent back from St. Kilda, and on assurance that the fence was strong the whole party indulged in the luxury of a sea-bath. Then they strolled on the beach, dined at one of the restaurants for which St. Kilda is famous, and returned in the evening by railway to Melbourne. Frank and Fred thought it was very like an excursion to Coney Island, and Doctor Bronson fully agreed with them, except that he missed the broad ocean which spreads before the popular watering-place of New York.

"There's a fine watering-place at Queenscliff, at the entrance of Port Phillip Bay," said Mr. Manson, "where you can look out on the Pacific and can see and hear the surf breaking on the shore. There's a fort there to guard the entrance in case of war, and all ships are signalled from that point on their arrival. As St. Kilda is the Coney Island of Melbourne, Queenscliff may be called its Long Branch, as its distance is about thirty-two miles, and it can be reached both by railway and steamboat.

"Farther down the coast," said he, "there are other watering-places, and what with the mountains and the sea Melbourneites are well provided with retreats. Here is something interesting." As he spoke he took from his pocket a photograph, which Doctor Bronson examined attentively, and then passed it over to the youths. It represented some rocks which resembled pieces of artillery, and were overlooked by a head that reminded Frank of "The Old Man of the Mountain," in Franconia, New Hampshire.

"The height to the crown of the head," said Mr, Manson, "is twenty-four feet, and the tuft of coast scrub that has found sufficient soil to cling to it in the cleft of the rock increases the resemblance to a head by representing hair. The guns are more realistic when viewed from another angle; near them are some spherical blocks of sandstone that might almost serve as cannon-balls. The head has been named the 'Sentinel,' and is also called the Sphinx; it is on the southern coast of Victoria, and about eight miles from Lorne, which has a growing popularity as a watering-place. The rocks resembling cannon are known as 'The Artillery Rocks.'"

Frank and Fred hoped they would have an opportunity to visit this natural curiosity, but circumstances did not favor them, as Lorne was too far away from the route of travel to justify the detour.

The day after their visit to St. Kilda they were taken on a steamboat excursion to Geelong, a pretty and well-built city on the shores of an arm of Port Phillip Bay, and about forty-five miles from Melbourne. It is famous for its woollen mills, tanneries, and other manufactories, and at one time its inhabitants firmly believed that it would be a successful rival of Melbourne on account of the superior advantages of its harbor and its greater nearness to the ocean.

It is said that the Geelong people caused a railway to be built between that city and Melbourne in the expectation that all the wool shipped at Melbourne would be brought to their city, which would also be the landing-place of all the goods destined for Melbourne. The result was exactly the reverse, the railway serving to take from Geelong most of the foreign trade it already possessed and carry it to Melbourne. Cargoes of wool are shipped from there still, but they are few in number when compared with those from Melbourne.

THE ARTILLERY ROCKS, NEAR LORNE, ON THE COAST OF VICTORIA.

Before the mail closed for America, Frank and Fred busied themselves with a large number of papers, which they sent to friends at home. They included the Age and the Argus, dailies which reminded them of The London Times or Daily News, The Illustrated Australian News and The Illustrated Sketcher, pictorials making their appearance monthly, a dozen or more weekly and monthly papers, some of them of Brobdingnagian proportions, and representing all shades of religious, social, and political feeling, and a quarterly called The Imperial Review. In a letter to his mother Frank said they had visited the office of The Melbourne Age at the invitation of one of its proprietors, and had come away with the belief that few people in the northern hemisphere had a just appreciation of the journalistic skill and enterprise of the antipodes.

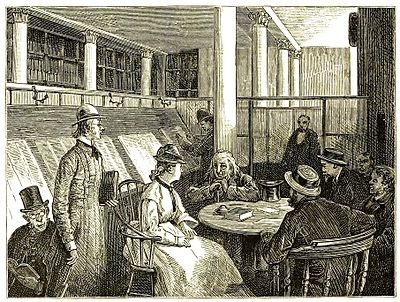

WAITING TO SEE THE EDITOR.

"It is evident," continued Frank, "that there are many waifs and strays in the population of Australia, if we are to judge by the advertising columns of the newspapers. All the leading dailies have advertisements headed 'Missing Friends,' and sometimes there will be a whole column of these inquiries for persons about whom information is desired by their friends. Here is one of them:

"'Robert Wiffen, arrived at Melbourne by ship Covenanter on Christmas Day, 1852, and was last heard of in 1867. Any information respecting him will greatly oblige.'…

"What volumes might be written by the novelist if he knew all the inside history covered by the 'Missing Friends' column of The Melbourne Age or The Sydney Herald for a single twelvemonth!"

DISTRIBUTING PAPERS TO NEWSBOYS.