The Boy Travellers in the Russian Empire/Chapter 20

CHAPTER XX.

WHILE our friends were listening to Mr. Hegeman's account of the journey through Siberia, the boat was continuing steadily on her course down the Volga. One of her passengers was a Russian count on the way to his estate, from which he had been absent for nearly two years. He had notified his people of his coming, and when the steamer stopped at the village where he was to land, there was quite an assemblage ready to meet him.

Doctor Bronson ascertained that they would remain at the landing an hour or more, as there was a considerable amount of freight to be put on shore. The party prepared to spend the time on land, and quite unexpectedly Frank and Fred were treated to a curious and interesting spectacle. It was the welcome of the count by his people, in accordance with Russian custom.

As he ascended the bank to the village, he was met by a procession of men, women, and children. It was headed by four venerable men with long, flowing beards, and dressed in the sheepskin coats with which we have been made familiar. One of the men in front carried a dish on which was a loaf of bread, and his comrade had another dish filled with salt. One man of the second couple carried a jug or pitcher of water. The Doctor explained to the youths that the presentation of bread, salt, and water was a ceremonial of Russian hospitality of very ancient date.

The men bowed low as they approached the count; on his part he urged them to stand upright and regard him as their friend. They halted directly in front of him, and then the bearer of the bread spoke in dignified tones as follows:

"We come, most noble master, to give the welcome of our village, and present you such food as we can offer, according to the ancient custom of our country."

In a few kindly words the count thanked them for their hospitality, and wished that their lives would be prosperous and happy. Then he cut a slice out of the loaf of bread and ate it, after dipping it in the salt. Next he drank a glass of the water, pouring it from the pitcher with his own

hands. When he had finished he again thanked the men for their hospitality, and asked them to give his good wishes to all the people. This ended the ceremony, and the count was then at liberty to enter the carriage that stood waiting, and ride to his house, some distance back from the river.

Doctor Bronson explained that bread and salt have a prominent place in Russian ceremonials, not only of welcome, but at weddings and on other occasions. The bread is invariably the rye or black bread of the country, and the guest to whom it is offered would show great rudeness if he declined to partake of it. A knife lies on the top of the loaf; the guest himself cuts the loaf, and must be careful to dip the slice in the salt before placing it in his mouth.

In their descent of the Volga, our friends passed a succession of villages on either bank, and occasionally a town or city of importance. The day after leaving Kazan they stopped at Simbirsk, the capital of the province of the same name, and the centre of a considerable trade. It is on the right bank of the river, and has a population of twenty-five or thirty thousand.

About a hundred miles farther down the Volga is Samara, which generally resembles Simbirsk, but is larger, and possesses a more extensive commerce. A railway extends from Samara to Orenburg, on the frontier of Siberia. On the other side of the Volga Samara is connected with the railway system which has its centre at Moscow. With railway and river to develop its commerce, it is not surprising that the place is prosperous, and has grown rapidly since the middle of the century.

Mr. Hegeman told the youths that many Swiss and Germans were settled along this part of the Volga, and he pointed out some of their villages as the boat steamed on her course. The Government allows them perfect freedom in religious matters, and they have an excellent system of schools which they manage at their own expense and in their own way. In other respects they are under the laws of the Empire, and their industry and enterprise have had a beneficial effect upon their Muscovite neighbors. The first of these settlers came here more than a hundred years ago; their descendants speak both German and Russian, and form quite an important part of the population.

Larger than Simbirsk and Samara rolled into one is Saratov, about a hundred miles below the city we have just described. It contains nearly a hundred thousand inhabitants; its houses are well built and spacious, and its streets are unusually broad, even for Russia. Our friends took a carriage-ride through the city, visited several of its sixteen or eighteen churches, and passed an hour or more in one of the factories devoted to the manufacture of leather goods.

Frank and Fred thought the churches were fully equal to those of any other Russian city they had seen, with the exception of a few of the most celebrated, and they greatly regretted their inability to make a fuller inspection of the place. But they consoled themselves with the reflection that they had seen the principal cities of the Empire, and the smaller ones could not offer many new and distinctive features.

In the province of Saratov they were on the border of the region of the Don Cossacks, and at some of the landings they had glimpses of this primitive people. Their country did not seem to be well cultivated, and Doctor Bronson told the youths that the Don Cossacks were more noted for skill in horsemanship than for patient industry. They prefer the raising of cattle, sheep, and horses to the labor of the field, and though many of them have accumulated considerable wealth they have little inclination for luxurious living.

An amusing scene at one of the landings was the Cossack method of shoeing an ox. Frank thus describes it:

"The poor beast was flung upon his side and firmly held down by half a dozen men, while his legs were tied together in a bunch. Then he was turned upon his back, so that his feet were uppermost, giving the blacksmith an excellent opportunity to perform his work. The blacksmith's 'helper' sat upon the animal's head to keep him from rising or struggling; the unhappy ox indicated his discomfort and alarm by a steady moaning, to which the operators gave not the least attention.

"At a shop in one of the villages we bought some souvenirs. Among them was a whip with a short handle and a braided lash, with a flat piece of leather at the end. The leather flap makes a great noise when brought down upon a horse's sides, but does not seem to hurt him much; crackers, like those on American and English whips, seem to be unknown here, at any rate we did not see any.

"The handle of the whip is sometimes utilized as the sheath of a knife. The one we bought contained a knife with a long blade, and reminded us of the sword-canes of more civilized countries."

"We stopped at Tsaritsin," said Fred, in his journal, "and had a short run on shore. At this point the Volga is only forty miles from the river Don, which empties into the Sea of Azof, and is navigable, in time of high water, about eight hundred miles from its mouth. There is a railway connecting the rivers, and also a canal; the latter is much longer than the railway, and was made by utilizing the channels of some little streams tributary to the rivers, and connecting them by a short cut.

"The Don is connected with the Dneiper as well as with the Volga; the three rivers form an important part of the great net-work of water communication with which Russia is supplied. The Dneiper enters the Black Sea at Kherson, near Odessa; next to the Volga it is the largest river of European Russia, and flows through a fertile country. It is about twelve hundred miles long, and its navigation was formerly much obstructed by rapids and other natural obstacles. Many of these hinderances have been removed by the Government, but the river has lost some of its commercial importance since the railways were established.

"From Tsaritsin to Astrachan there is not much of interest, as the country is generally low and flat, and the towns and villages are few in number. Much of the country bordering the river is a marsh, which is overflowed at the periods of the annual floods, and therefore is of little value except for the pasturage of cattle.

"As we approached the mouth of the Volga we found the river divided into many channels; in this respect it resembles the Nile, the Ganges, the Mississippi, and other great watercourses of the globe. On one of these channels the city of Astrachan is built. It is not on the mainland, but on an island. Another channel passes not far from the one by which we came, and maintains a parallel course for a considerable distance.

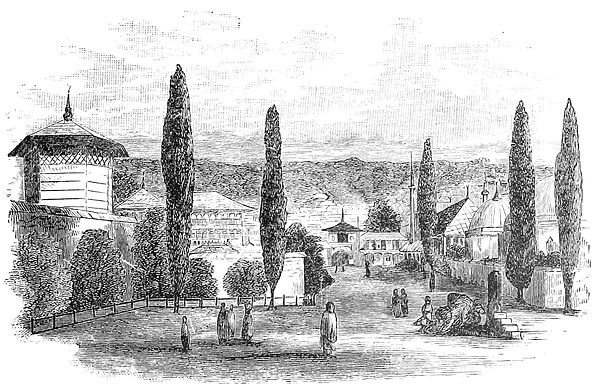

"Astrachan is the most cosmopolitan city we have seen in Russia, even more so than Kazan. The character of its seventy or eighty thousand inhabitants may be understood when I tell you that it has thirty-seven Greek churches, two Roman Catholic, two Armenian, and one Protestant, and is the seat of a Greek archbishop and an Armenian bishop. Then it has an Indian temple, fifteen mosques, and a Chinese pagoda. It has a botanical garden, an ecclesiastical school, schools of all the grades peculiar to the large towns of Russia, a naval academy, and I don't know how many other institutions. Books are printed here in Russian, Tartar, and other languages, and as you walk through the bazaars your ears are greeted by nearly all the tongues of Europe and Asia.

"To get at the cosmopolitan peculiarities of the city we were obliged to go through narrow and dirty streets, which somewhat marred the pleasure of our visit. In this respect Astrachan is more Oriental than Russian; its history dates beyond the time of the Russian occupation of the lower Volga, and therefore we must expect it to have Oriental features in preponderance.

"In commercial matters Astrachan is important, as it stands between Europe and Central Asia, and exchanges their goods. Great quantities of raw and embroidered silks, drugs, rhubarb, hides, sheepskins, tallow, and other Asiatic products come here, and in return for them the Russians dispose of cotton and other manufactures suited to the wants of their Kirghese and Turcoman subjects or neighbors.

"We are told that there are more than a hundred manufacturing establishments in Astrachan. Vast quantities of salt are made here or in the immediate vicinity, and the fisheries of the Volga and the Caspian Sea, which is only twenty miles away, are among the most important in the world. Unfortunately the harbor is so much obstructed by sand that only vessels of light draught can reach it from the Caspian. Since the opening of the railway connecting the Caspian with the Black Sea, much of the commerce which formerly came to Astrachan is diverted to the new route.

"We landed from the steamer and were taken to a hotel which promised very poorly, and fully sustained its promise. But any lodging was better than none at all, and as we were to remain only long enough to get away, it didn't much matter. We breakfasted on the steamer just before leaving it, and had no use for the hotel for several hours.

"In our sight-seeing we went to a Tartar khan, or inn, a large building two stories high and built around a court-yard, in accordance with the Tartar custom. The court-yard receives wagons and horses, while the rooms that front upon it are rented to merchants and others who desire them. The master of the place will supply food to those who expressly ask for it, and pay accordingly, but he is not expected to do so.

"Travellers pick up their food at the restaurants in the neighborhood, and either bring it to their quarters or devour it at the place of purchase. A corridor runs around each story of the khan, and the rooms open upon this corridor.

"Under one of the stair-ways there is a room for the Tartar postilions who care for the horses of travellers. With their round caps, loose garments, and long pipes they formed a picturesque group around a fire

where one of their number was watching the boiling of a pot which probably contained their dinner.

"In the last few years Astrachan has developed quite an important trade in petroleum, in consequence of the working of the wells at Baku, on the western shore of the Caspian. Steamers and sailing-vessels bring it here in immense quantities, and from Astrachan it is shipped by the Volga to all parts of Russia, and also to Germany and other countries. There are several machine-shops for the repair of steamships, steamboats, and barges engaged in the oil trade. The oil business of the Caspian region is growing very rapidly, and promises to make a serious inroad upon the petroleum industry of the United States.

"There is a line of steamers on the Caspian Sea for the transport of petroleum; they are constructed with tanks in which the oil is carried in bulk, and their engines are run by petroleum instead of coal. Their accommodations for passengers are limited, but as the voyage is made in a couple of days we were not particular, and took places on the first vessel that offered.

"Owing to the shallowness of the lower Volga the oil-steamers, excepting some of the smaller ones, do not come to Astrachan, but transfer their cargoes at 'Diavet Foot' (Nine Feet), which is so called from its depth of water. Diavet Foot is eighty miles from Astrachan, and on a shoal which spreads ont like a fan beyond the mouth of the Volga. A small steamer having several barges in tow took us to the shoal, where we were

transferred to the Koran, a handsome steamer two hundred and fifty-two feet long and twenty-eight feet broad. There was a large fleet of river-boats, barges, and sea-steamers at Diavet Foot, and we watched with much interest the process of transferring kerosene from the tank-steamers which had brought it from Baku to the barges for conveyance up the river."

An English gentleman, who was connected with the petroleum works at Baku, kindly gave the youths the following information:

"There are nearly a hundred steamers on the Caspian engaged in the oil traffic. They are of iron or steel, average about two hundred and fifty feet in length by twenty-seven or twenty-eight in breadth, and carry from seven hundred to eight hundred tons (two hundred thousand to two hundred and fifty thousand gallons) of petroleum in their tanks. Their engines are of one hundred and twenty horse-power, and make a speed of

TARTAR PALACES IN SOUTHERN RUSSIA.

ten knots an hour; they use petroleum for fuel, and it is estimated that their running expenses are less than half what they would be if coal were burned instead of oil. The steamers were built in Sweden or England, and brought through from St. Petersburg by means of the canals connecting the Volga with the Neva. Some of the largest steamers were cut in two for the passage of the canals, the sections being united at Astrachan or Baku.

"The oil-steamers for river work are from sixty to one hundred and fifty feet long; they are fitted with tanks, like the sea-steamers, and are powerful enough for towing tank-barges in addition to the transport of their own loads. They run from Diavet Foot to Tsaritsin, four hundred miles up the Volga, the first point where there is railway connection to Western Europe. Some of them proceed to Kazan, Nijni Novgorod, and other points on the upper Volga, and also through the canals to St. Petersburg, but the greater part of them land their cargoes at Tsaritsin.

"When you get to Baku you will see how rapidly the loading of the steamers is performed. When a steamer is ready for her cargo, an eight-inch pipe pours the kerosene into her tanks, and fills her in about four hours. Then she starts for Diavet Foot, where the oil is pumped into the river steamers and barges; she fills her tanks with fresh water, partly in order to ballast her properly, and partly because water is very scarce at Baku, and then starts on her return. Five or six days make a round trip, including the loading and unloading at either end of the route.

"At Baku the water is pumped into reservoirs, to be used in the refineries or for irrigating the soil in the vicinity of the works, and then the

GYPSY FAMILY AT ASTRACHAN.

steamer is ready for her load again. From Tsaritsin the oil is carried in tank-cars similar to those you have in America. I can't say exactly how many tank-cars are in use, but think the number is not much below three thousand. Twenty-five cars make an oil-train, and these oil-trams are in constant circulation all over the railways of Russia and Western Europe."

Frank asked if the enterprise was conducted by the Government or by individuals.

"It is in the hands of private parties," said the gentleman, "who are

AN OIL-STEAMER ON THE CASPIAN SEA.

generally organized into companies. The leading company was founded by two Swedes, Nobel Brothers, who have spent most of their lives in Russia, and are famous for their ingenuity and enterprise. The petroleum industry of Baku was practically developed by them; they originated the idea of transporting the Baku petroleum in bulk, and the first tank-steamer on the Caspian was built by them in 1879, according to the plans of the elder brother.

"Bear in mind that the Volga is frozen for four months in the year, at the very time when kerosene is most in demand for light. Nobel

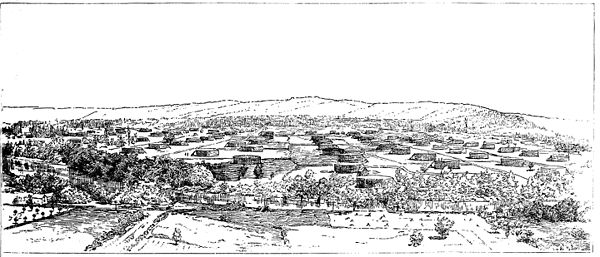

TANKS AT A STORAGE DEPOT.

Brothers arranged for a system of depots throughout Russia and Germany, where oil could be stored in summer for distribution in winter. The largest of these depots is at Orel, and there are four other large depots at St. Petersburg, Moscow, Warsaw, and Saratov.

"The depot at Orel can receive eighteen million gallons, and the four other large depots about three million gallons each. The smaller depots, together with the depot at Tsaritsin, make a total storage capacity of between fifty and sixty million gallons of petroleum available for use when the Volga is frozen and traffic suspended.

"All this was done before the completion of the railway between the Caspian and Black seas. The line from Batoum, on the Black Sea, by

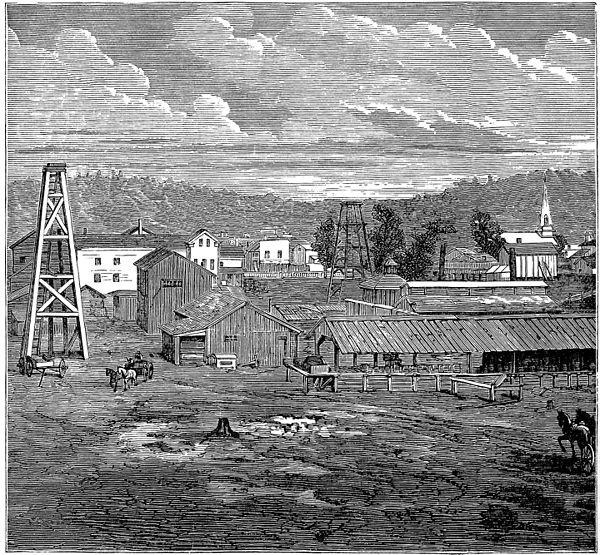

VIEW IN AN OIL REGION.

way of Tiflis to Baku, on the Caspian, was opened in 1883, and immediately about two hundred tank-cars were set to carrying oil to where it could be loaded into steamers for transportation to the ports of the Mediterranean and to England. A pipe-line similar to what you have in America to connect your oil regions with the seaboard, will probably be established before long between Baku and Batoum; the oil will be pumped from Baku to the crest of the pass through the Caucasus Mountains, and from there it will run by gravity like a mountain stream down to the shores of the Black Sea. There it can be loaded into tank-steamers, or placed in barrels for distribution wherever it can find a market.

"Perhaps I may be building castles in the air," said the gentleman, "since I am not of your nationality, but I look upon the European market for American petroleum as doomed to destruction. The Baku petroleum has driven your American product from Russia, and is rapidly driving it from the markets of Germany, France, and Austria. We think it quite equal to your petroleum, and in some respects superior. American oilmen claim that theirs is by far the better article, and as each side can bring the opinions of scientists to prove the correctness of its claim, the question resolves itself into one of cheapness of production and transportation. For the market of Europe and Asia we think we have a great advantage in being nearer to it. It is as far from Batoum to England as from New York, and therefore you may be able to supply Great Britain with petroleum, by reason of the cost of transportation.

"Two plans are under consideration for overcoming the disadvantages of the closing of the Volga route by ice for one-third of the year. Look on the map of Russia and see the position of Vladikavkaz at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains. The railway reaches that point, and it has been proposed to extend it to a connection with the Batoum-Baku line at Tiflis, a distance of one hundred and ten miles. The line would be very costly, as it must run through the Caucasus range; a longer but less expensive line would be from Vladikavkaz to Petrovsk, on the shore of the Caspian Sea, half way between Baku and the mouth of the Volga. It could be reached in a day by the tank-steamers from Baku, and communication is open for the entire year.

"Since either of these lines would be useful for strategic purposes as well as for commerce, it is probable that one or both of them will be built within the next few years. They would be useful for the supply of Russia and Germany in the winter season, and render the enormous storage depots less necessary than they are at present.

"The Baku petroleum is utilized not only for making kerosene, but for the manufacture of lubricating oils and for liquid fuel for steam-ship, railway, and other purposes. The oil refuse is burned on the steamer, and railways; for the last two or three years it has been employed by the Tsaritsin-Griazi

A SPOUTING WELL.

DERRICKS AND TANKS IN THE AMERICAN OIL REGION.

Railway Company in its locomotives, where it has completely taken the place of coal. It is the only fuel used by the Trans-Caucasian railway from Baku to Batoum and Poti, and wherever it has been tried in competition with coal brought from great distances, it has been adopted. I wonder you don't make use of it in America."

Doctor Bronson suggested that probably the reason why liquid fuel had not taken the place of coal in America, was in consequence of the relative prices of the two substances. "In Russia," said he, "coal is dear; in America it is cheap, and our coal-fields are exhaustless. Three hundred thousand tons of coal have been carried annually from England to the Black Sea; it retails there for ten or twelve dollars a ton, which would be an enormous price in America. Now what will your petroleum fuel cost at Batoum?"

"The present price," said his informant, "is twenty-six English shillings (nearly seven dollars) a ton. Weight for weight, it is cheaper than coal; one ton of it will make as much steam as two tons of coal, and thus you see there is an enormous saving in cost of fuel. Then add the saving in wages of stokers, the additional space that can be given to cargo, and the gain in cleanliness, as the liquid fuel makes neither smoke nor cinders.

"The Russian Government is making experiments at Sebastopol with a view to adopting astaki, as petroleum refuse is called, as the fuel for its men-of-war. I predict that as fast as the furnaces can be changed you will see all steamers on the Black Sea burning the new substance instead of the old. Come with me and see how the liquid fuel works."

"He led the way to the engine-room of the steamer," said Frank, in his journal, "and asked the engineer to show us how the machinery was propelled.

"The process is exceedingly simple. Small streams of petroleum are caught by jets of steam and turned into vapor; the vapor burns beneath the boilers and makes the steam, and that is all. The flow of steam and oil is regulated by means of stopcocks, and steam can be made rapidly or slowly as may be desired.

"Our friend told us that a fire of wood, cotton-waste, or some other combustible is used to get up steam at starting. This is done under a small boiler distinct from the main ones, and it supplies steam for the 'pulverizer,' as the petroleum furnace is called.

"When steam is on the main boilers the small one is shut off and the fire beneath it is extinguished. Even this preliminary fire is rendered unnecessary by a newly invented furnace in which a quantity of hydro-carbon gas is kept stored and in readiness. We were told that the action of the pulverizer is so simple that after the engineers have adjusted the flame at starting and put the machinery in operation, they do not give them any attention till the end of the voyage. One stoker, or fireman, is sufficient to watch all the furnaces of a ship and keep them properly supplied with astaki."

AN OIL REFINERY WITH TANK CARS.

A good many additional details were given which we have not space to present. The study of the petroleum question occupied the attention of the youths during the greater part of the voyage, and almost before realizing it they were entering the Bay of Baku, and making ready to go on shore.

Frank and Fred were astonished at what they saw before them. Baku is on a crescent-shaped bay, and for a distance of seven or eight miles along its shores there is a fringe of buildings on the land, and a fringe of shipping on the water. Thirty or forty piers jut from the land into the bay; some of the piers were vacant, while others had each from three to half a dozen steamers receiving their cargoes or waiting their turns to be filled. Not less than fifty steamers were in port, and there were several hundred sailing craft of various sizes and descriptions riding at anchor or tied up at the piers. It was a busy scene—the most active one that had greeted their eyes since leaving the fair at Nijni Novgorod.

They landed at one of the piers, and were taken to a comfortable hotel facing the water, and not far away from it. The youths observed that the population was a cosmopolitan one, quite equal to that of the fair-grounds of Nijni; Russians, Armenians, Turcomans, Kirghese, Persians, Greeks, all were there together with people of other races and tribes they were unable to classify. The streets were filled with carts and carriages in great number, and they found on inquiry that almost any kind of vehicle they desired could be had with little delay.

Doctor Bronson and his young friends had visited the petroleum region of their own country, and very naturally desired to see its formidable rival.

They learned that the wells were eight or ten miles from Baku, and as it was late in the day when they arrived, their visit was postponed till the following morning.

Securing a competent guide they engaged a carriage, and early the next day left the hotel for the interesting excursion. We will quote Frank's account of what they saw:

"We found the road by no means the best in the world," said the youth, "as no effort is made to keep it in repair, and the track is through a desert. On our right as we left Baku is the Chorney Gorod, or Black Town, which contains the refineries; it reminded us of Pittsburg, with its many chimneys and the cloud of smoke that hung over it. Then we crossed the track of the railway, and the lines of pipe that supply the refineries with oil. Right and left of us all over the plain there are reservoirs and pools of petroleum; there are black spots which indicate petroleum springs, and white spots denoting the presence of salt lakes. By-and-by we see a whole forest of derricks, which tells us we are nearing Balakhani, the centre of the oil-wells.

"Passing on our left the end of a salt lake five or six miles long, we enter the region covered by these derricks, and our guide takes us to the Droojba well, which spouted a stream of petroleum three hundred feet high when it was opened. Two million gallons of petroleum were thrown out daily for a fortnight or more from this one well, and two months after it was opened it delivered two hundred and fifty thousand gallons daily. Our guide said it ruined its owners and drove them into bankruptcy!

"You will wonder, as we did, how a discovery that ought to have made a fortune for its owners did exactly the reverse. We asked the guide, and he thus explained it:

"'The Droojba Company had only land enough for a well, and none for reservoirs. The oil flowed upon the grounds of other people, and became their property. Some of it was caught on waste ground that belonged to nobody, but the price had fallen so low that the company did not realize from it enough to pay the claims of those whose property was

ANCIENT MOUND NEAR THE CASPIAN SEA.

damaged by the débris that flowed from the well along with the petroleum. In this region considerable sand comes with the oil. The sandy product of the Droojba well was very large, and did a great deal of damage. It covered buildings and derricks, impeded workings, filled the reservoirs of other companies or individuals, and made as much havoc generally as a heavy storm.'

"The process of boring a well is very much the same as in America, and does not merit a special description. The diameter of the bore is larger than in America; it varies from ten to fourteen inches, and some of the wells have a diameter of twenty inches. Oil is found at a depth of from three hundred to eight hundred feet. Every year the shallow wells are exhausted, and new borings are made to greater depths; they are nearly always successful, and therefore, though the petroleum field around Balakhani is very large, the oil speculators show no disposition to go far from the original site. To do so would require a large outlay for

CURIOUS ROCK FORMATIONS.

pipe-lines, or other means of transporting the product, and as long as the old spot holds out they prefer to stick to it.

"Our guide said there were about five hundred wells at Balakhani; there are twenty-five thousand wells in America, but it is claimed that they do not yield as much oil in the aggregate as the wells in this region.

"From the wells the oil is conducted into reservoirs, which are nothing more than pits dug in the earth, or natural depressions with banks of sand raised around them. Here the sand in the oil is allowed to settle; when it has become clear enough for use the crude petroleum is pumped into iron tanks, and then into the pipe-lines that carry it to the refineries in Chorney Gorod.

"Some of the ponds of oil are large enough to be called lakes, and there are great numbers of them scattered over the ground of Balakhani.

MODERN FIRE-WORSHIPPERS—PARSEE LADY AND DAUGHTER.

The iron cisterns or tanks are of great size; the largest of them is said to have a capacity of two million gallons.

"There is no hotel, not even a restaurant, at Balakhani, and we should have gone hungry had it not been for the caution of the hotel-keeper, who advised us to take a luncheon with us. The ride and the exertion of walking among the wells gave us an appetite that an alderman would envy, and we thoroughly enjoyed the cold chicken, bread, and grapes which we ate in the carriage before starting back to the town. We reached the hotel without accident, though considerably shaken up by the rough road and the energetic driving of our Tartar coachman."

While Frank was busy with his description, Fred was looking up the history of the oil-wells of Baku. Here is what he wrote concerning them:

"For twenty-five hundred years Baku has been celebrated for its fire-springs, and for a thousand years it has supplied surrounding nations and people with its oil. From the time of Zoroaster (about 600 b. c.) it has been a place of pilgrimage for the Guebres, or Fire-worshippers, and they have kept their temples here through all the centuries down to the present day. At Surukhani (about eight miles from Baku and four or five from Balakhani) there are some temples of very ancient date; they stand above the mouths of gas-wells, and for twenty centuries and more the Fire-worshippers have maintained the sacred flame there without once allowing it to become extinct. On the site of Baku itself there was for centuries a temple in which the sacred fire was maintained by priests of Zoroaster until about a. d. 624. The Emperor Heraclius, in his war against the Persians, extinguished the fires and destroyed the temple.

"Since the eighth century, and perhaps earlier, the oil has been an article of commerce in Persia and other Oriental countries. Read what Marco Polo wrote about it in the thirteenth century:

"'On the confines of Georgine there is a fountain from which oil springs in great abundance, inasmuch as a hundred ship-loads might be taken from it at one time. This oil is not good to use with food, but 'tis good to burn, and is used also to anoint camels that have the mange. People come from vast distances to fetch it, for in all countries there is no other oil.'

"It is probable that the good Marco means camel-loads rather than ship-loads—at least that is the opinion of most students of the subject. The fire-temple of the Guebres is a walled quadrangle, with an altar in the centre, where the fire is kept; the sides of the quadrangle contain cells where the priests and attendants live, and in former times there were frequently several thousands of pilgrims congregated there. We were told that the place would not repay a visit, and therefore we have not gone there, as we are somewhat pressed for time, and the journey is a fatiguing one.

"For a considerable space around the temple there are deep fissures in the ground whence the gas steadily escapes. Before the Russians

A BURNING TANK.

occupied the country there was an annual sacrifice by the Fire-worshippers. A young man was thrown into one of the fissures, where he perished, though some writers assert that he leaped voluntarily, through the persuasion of the priests.

"Though famous through many centuries, and carried thousands of miles east and west for purposes of illumination, the oil of Baku was never gathered in large quantities until the present century, and the exploitation of the oil-fields on a grand scale is an affair of the last twenty years.

"In 1820 it was estimated that the yield of the Baku oil-wells was about four thousand tons of naphtha, of which the greater part was sent to Persia. The annual production remained about the same until 1860, when it was 5484 tons; in 1864 it was 8700 tons; in 1870, 27,500; and in 1872, 24,800 tons. Down to that time the Government held a monopoly of the oil-fields, and levied a royalty for operating them. In 1872 the monopoly was removed, and the lands were offered for sale or long lease.

"There was a rush of speculators to the oil fields, stimulated by the knowledge of what had been accomplished in America. Sixty-four thousand tons were produced in 1873, 94,000 in 1875, 242,000 in 1877, 420,000 in 1880, 800,000 in 1883, and over 1,000,000 tons in 1884. In 1885 the total quantity of raw petroleum pumped or received from the wells was 105,000,000 poods, or nearly 2,000,000 tons. Twenty-seven million poods, or nearly 500,000 tons, were distilled at Baku. The largest portion,

A RISE IN OIL. two-thirds at least, was sent off by sea to Astrachan, and thence up the Volga, to be forwarded by tank-cars for distribution to all parts of Russia and to Baltic ports, and thence to Germany and England. About 7,250,000 poods have been shipped by the Trans-Caucasian Railway to Batoum, on the Black Sea, going thence to the Danube, to Odessa, to Marseilles, and some by the Suez Canal to India and China. Every day large trains of tank-cars leave Baku via Tiflis for Batoum, and a pipe-line from Baku to Batoum may be looked for before long.

"Down to 1870 the oil was taken from pits which were dug like ordinary wells; boring began in that year on the American system, and the first bored well went into operation, the oil being pumped out by the ordinary pumping machinery.

"The first flowing well, or fontan (fountain), as it is called here, was struck in 1873. In that year there were only seventeen bored wells in operation, but by the end of 1874 there were upward of fifty. The flowing wells cease to flow after a time, varying from a few weeks to several months; one well spouted forty thousand gallons of oil daily for more than two years, and afterwards yielded half that amount as a pumping well. The history of many wells of this region is like a chapter from the 'Arabian Nights.'

"We are in the midst of oil, and shall be as long as we remain at Baku. There are pools of oil in the streets; the air is filled with the smell of oil; the streets are sprinkled with oil, as it is cheaper and better than water; ships and steamers are black and greasy with oil, and even our food tastes of oil. Everybody talks oil, and lives upon oil (figuratively, at least), and we long to think of something else."