The Boy Travellers in the Russian Empire/Chapter 23

CHAPTER XXIII.

FOR fifty miles after leaving Baku the railway follows the coast of the Caspian Sea until it reaches Alayat, where the Government is establishing a port that promises to be of considerable importance at no distant day. The country is a desert dotted with salt lakes, and here and there a black patch indicating a petroleum spring. The only vegetation is the camel-thorn bush, and much of the ground is so sterile that not even this hardy plant can grow. Very little rain falls here, and sometimes there is not a drop of it for several months together.

At Alayat the railway turns inland, traversing a desert region where there are abundant indications of petroleum; in fact all the way from Baku to Alayat petroleum could be had for the boring, and at the latter place several wells have been successfully opened, though the low price of the oil stands in the way of their profitable development. After leaving the desert, a region of considerable fertility is reached. The streams flowing down from the mountains are utilized for purposes of irrigation, but very rudely; under a careful system of cultivation the valley of the Kura River, which the railway follows to Tiflis, could support a large population.

From Baku to Tiflis by railway is a distance of three hundred and forty-one miles, and the line is said to have cost, including rolling stock, about fifty thousand dollars a mile. In the work on the desert portion many of the laborers died from the effects of the extreme dryness of the atmosphere. The whole distance from Baku to Batoum, on the Black Sea, is five hundred and sixty-one miles.

Tiflis is thirteen hundred and fifty feet above the level of the sea, and the point where the railway reaches its greatest elevation is eighteen hundred feet higher, or thirty-two hundred feet in all. The grades are very steep; there is one stretch of eight miles where it is two hundred and

forty feet to the mile, and for a considerable distance it exceeds one hundred feet to the mile. It is proposed to overcome the steepest grade by a long tunnel which would reduce the highest elevation to little more than two thousand feet.

Our friends reached Tiflis in the evening, after an interesting ride, in spite of the monotony of the desert portion of the route. Frank will tell us the story of their visit to the famous city of the Caucasus.

"We were somewhat disappointed," said he, "with our first view of Tiflis. We had an impression that it was in the centre of a fertile plain surrounded by mountains; actually the ground on which it stands is not fertile, and the surroundings consist of brown hills instead of mountains. The sides of the hills are barren, and there would hardly be a shrub or tree in the city were it not for the system of irrigation which is maintained. The prettiest part of the city is the quarter occupied by the Germans, where there are rows and groups of trees and a great many luxuriant gardens. The Germans are descended from some who came here in the last century to escape religious persecution. Though born in Tiflis and citizens of Russia, in every sense they preserve their language and customs, and do not mingle freely with their Muscovite neighbors.

"There are about one hundred and ten thousand inhabitants in Tiflis; nearly one-third are Russians, rather more than a third Armenians, twenty-three thousand Georgians, and the rest are Germans, Persians, and mixed races in general. Most of the business is in the hands of the Armenians, and many of them are wealthy; nearly all speak Russian, and mingle with the Russians more harmoniously than do any of the others. The Persians live in a quarter by themselves, and it is by no means the cleanest part of the city. The Georgians preserve their dress and language, and, though entirely peaceful, are said to maintain the same hatred to Russia as when fighting to preserve their independence.

"Many of the officials in the Caucasus are Armenians, and some of the ablest generals of the Russian army belong to the same race. Gen. Loris Melikoff is an Armenian, and so are Generals Lazareff and Tergoukasoil, as well as others of less importance. The Armenians have four newspapers at Tiflis, and four monthly reviews. There are nearly a million of these people in Russia and the Caucasus, and their treatment is in marked contrast to that of the eight hundred thousand Armenian subjects of Turkey who have been most cruelly oppressed by the Sultan and his officers.

"We had read of the beauty of the Georgians, who used to sell their daughters to be the wives of the Turks, and naturally looked around us for handsome faces. We saw them among the men as well as among the women; and we saw more handsome men than women, perhaps for the reason that men were much more numerous. The Georgians are a fine race of people, and so are all the natives of the Caucasus. The mountain air all the world over has a reputation for developing strength and intelligence among those who breathe it.

"Since the occupation of Georgia and the other parts of the Caucasus by Russia, the people are no longer sold as slaves for Turkish masters. Whatever may be the faults of the Russian rule, it is certainly far in advance of that of Turkey.

VIEW OF TIFLIS. "Tiflis may be said to be in two parts, the old and the new. The former is on the bank of the river, and its streets are narrow and dirty; the new part is on higher ground, and has been chiefly built by the Russians since they obtained possession of the country. In this part the streets are wide, and lined with many handsome buildings; in the old part there are several Armenian churches and caravansaries, and the greater portion of the commerce is transacted there.

"We saw a great many Russian soldiers, and were told that a large garrison is always maintained in Tiflis, which is a central point from which troops can be sent in any direction. The Government offices and the palace of the Governor-general are in the Russian quarter, and of course there are plenty of Russian churches, with their gilded domes sparkling in the sunlight.

"We visited one of the churches, and also the Armenian Cathedral; we tried to see the interior of a mosque, but were forbidden admittance except on payment of more money than we chose to give. We drove to the hot baths, which are situated just outside the city; they are largely patronized, and have an excellent reputation for the relief of gout, rheumatism, and similar troubles. There are many hot springs in the neighborhood of Tiflis that have been flowing for centuries, without any change in temperature or volume.

"We wanted to go overland to Vladikavkaz, for the sake of the journey among the Caucasus, but our plans were otherwise, and we continued by railway to Batoum. The mountains of this range are as picturesque as any we have ever seen. The passes are like those of the Alps or the Sierra Nevadas, and as we wound along the line of railway to the crest of the divide, every moment revealed a new and splendid picture. We had distant views of Elburz and Ararat, two of the most famous mountains of this region, and greatly regretted our inability to visit the latter, which is revered as the resting-place of Noah's Ark. Mount Ararat has been ascended by several travellers; they describe the journey as very fatiguing, but were amply repaid by the magnificent view from the summit.

"We left Tiflis dry and dusty, and the dry air remained with us till we crossed the ridge and began our descent. Then we entered the clouds, and as we passed below their level found ourselves in a pouring rain. The western slope of the Caucasus is a rainy region, while the eastern is dry. Baku has too little rain, and Batoum too much; the western slope is luxuriant, while the eastern is an arid desert, and the fertility of the former continues down to the shore of the Black Sea.

"Grapes and melons were offered at every station, at prices that were

THE PASS OF DARIEL, CAUCASUS. a marvel of cheapness. Two cents would buy a large melon, and the same money was gladly accepted for a bunch of grapes which would furnish a dinner for a very hungry man. A great deal of wine is raised in this region; three hundred thousand acres are said to be devoted to the culture of the grape in the Caucasus, and about forty million gallons of wine are made annually. Wine is plenty and cheap; the Russians refuse to drink the wine of the Caucasus, just as Californians affect to despise that of their own State. We are told that a large part of the so-called foreign wine sold in Tiflis and other cities of the Caucasus is really the product of the country under fictitious labels.

"We have already mentioned the use of petroleum in the locomotives of the Trans-Caucasian Railway. Where we stopped for fuel and water the petroleum-tank was side by side with the water-tank, and there was no sign of wood-yard or coal-heap. A few minutes charged the tender with petroleum and water, in separate compartments, and then we moved on, just as on any other railway line.

GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF THE CAUCASUS.

"It is delightful riding behind a petroleum locomotive, as there are neither cinders nor smoke. After the fire is started the furnace door is not opened; the fireman regards the flame through a hole about two inches square, and regulates it just as may be desired. They told us that steam could be more evenly maintained than with coal or wood; there was no excess of steam while waiting at stations, and consequently no necessity for 'blowing off.' Wonder what railway in America will be the first to adopt the new fuel?

"The Trans-Caucasian Railway was begun in 1871; its starting-point was at Poti, which has a poor harbor and stands in marshy ground, so that fevers and malaria are altogether too common. In 1878 Russia came into possession of Batoum, which has a good harbor, and immediately a branch line sixty miles long was built from that city to connect with the railway. Now nearly all the business has gone to Batoum. Poti is decaying very rapidly, but for military reasons it is not likely to be abandoned.

"By the treaty of Berlin Batoum was made a free port, and the Russians were forbidden to fortify it; but they have kept the Turkish fortifications, and not only kept them uninjured, but have repaired them whenever there were signs of decay. On this subject the following story is told:

"The casemated fortress which commands the port required to be strengthened in certain points, and the contractors were asked for estimates for the work. One man presented an estimate which he headed 'Repairs to Fortifications.' The general commanding the district immediately sent for the contractor, and said to him,

"'There are no fortifications in Batoum; they are forbidden by the treaty of Berlin. Your estimates must be for "garrison-barrack repairs." Remember this in all your dealings with the Government.'

"We were only a few hours in Batoum, as we embraced the

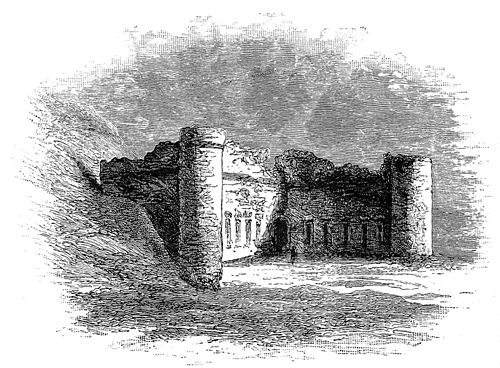

RUINED FORTRESS IN THE CAUCASUS.

opportunity to embark on one of the Russian Company's steamers for Sebastopol and Odessa. Batoum is growing very rapidly, and promises to be a place of great importance in a very few years. The old town of the Turks has given place to a new one; the Russians have destroyed nearly all the rickety old buildings, laid out whole streets and avenues of modern ones, extended the piers running into the sea, drained the marshes that formerly made the place unhealthy, and in other ways have displayed their enterprise. We were told that there is a great deal of smuggling carried on here, but probably no more than at Gibraltar, Hong-Kong, and other free ports in other parts of the world.

"And now behold us embarked on a comfortable steamer, and bidding farewell to the Caucasus. Our steamer belongs to the Russian Company of Navigation and Commerce, which has its headquarters at Odessa; it

sends its ships not only to the ports of the Black Sea, but to the Levantine coast of the Mediterranean, through the Suez Canal to India, and through the Strait of Gibraltar to England. A line to New York and another to China and Japan are under consideration; it is probable that the latter will be established before the Trans-Atlantic one. The company owns more than a hundred steamers, and is heavily subsidized by the Russian Government."

The first stop of the steamer was made at Trebizond, the most important port of Turkey, on the southern coast of the Black Sea. It has a population of about fifty thousand, and carries on an extensive commerce with Persia and the interior of Asiatic Turkey. Latterly its commerce has suffered somewhat by the opening of the Caspian route from Russia to Persia, but it is still very large.

Frank and Fred had two or three hours on shore at Trebizond, which enabled them to look at the walls and gardens of this very ancient city. Frank recorded in his note-book that Trebizond was the ancient Trapezius, and that it was a flourishing city at the time of Xenophon's famous retreat, which every college boy has read about in the "Anabasis." It was captured by the Romans when they defeated Mithridates. The Emperor Trajan tried to improve the port by building a mole, and made the city the capital of Cappadocian Pontus.

The Trebizond of to-day consists of the old and new town, the former surrounded by walls enclosing the citadel, and the latter without walls and

extending back over the hills. It has two harbors, both of them unsafe at certain seasons of the year. A few millions of the many that Turkey has spent in the purchase of cannon and iron-clad ships of war would make the port of Trebizond one of the best on the coast of the Black Sea.

Great numbers of camels, pack-horses, and oxen were receiving or discharging their loads at the warehouses near the water-front. Fred ascertained on inquiry that there were no wagon-roads to Persia or the interior of Asiatic Turkey, but that all merchandise was carried on the backs of animals. One authority says sixty thousand pack-horses, two thousand

camels, three thousand oxen, and six thousand donkeys are employed in the Persian trade, and the value of the commerce exceeds seven million dollars per annum.

"We are only a hundred and ten miles from Erzeroom," said Fred, "the city of Turkish Armenia, which is well worth seeing. Wouldn't it be fun to go there and have a look at a place that stands more than a mile in the air?"

"Is that really so?" Frank asked; "more than a mile in the air?"

"Yes," replied his cousin, "Erzeroom is six thousand two hundred feet above the level of the sea, and two hundred feet higher than the plain which surrounds it. It had a hundred thousand inhabitants at the beginning of this century, but now has about a third of that number, owing to the emigration of the Armenians after the war between Turkey and Russia in 1829. It is frightfully cold in winter and terribly hot in summer, but for all that the climate is healthy."

"How long will it take us to get there?"

"About fifty hours," was the reply. "We must go on horseback, but can return in forty hours, as the road descends a great part of the way from Erzeroom to Trebizond. Isn't it strange that with such an immense trade as there is between that place and this—for the road to Persia passes through Erzeroom—the Turks have been content with a bridle-path instead of a wagon-road, or, better still, a railway. Besides—"

Further discussion of the road to Erzeroom and the possibilities of travelling it were cut short by the announcement that it was time to return to the steamer. An hour later our friends saw the coast of Asiatic Turkey fading in the distance, as the steamer headed for Southern Russia.

Her course was laid for Sebastopol, the city which is famous for the long siege it sustained during the Crimean war, and for possessing the finest natural harbor on the Black Sea. Doctor Bronson suggested that the youths should dispose of the time of the voyage by reading up the history of that celebrated war, and particularly of the siege and capture of Sebastopol.

The weather was fine enough to tempt them to idleness, but Frank and Fred had a rule that when they had anything to do they would do it. Accordingly they busied themselves with the books at their command, and made the following condensed account of the contest of Russia with the nations of Western Europe:

"The Crimea was conquered by Russia in the time of Catherine the Great, and immediately after the conquest the Russians began to fortify the harbor of Sebastopol (Sacred City). When they went there they found only a miserable Tartar village called Akhtiar; they created one of the finest naval and military ports in the world, and built a city with broad streets and handsome quays and docks. In 1850 it had a population of about fifty thousand, which included many soldiers and marines, together with workmen employed in the Government establishments.

"In 1850 there was a dispute between France and Russia relative to the custody of the holy places in Palestine; there had been a contention concerning this matter for several centuries, in which sometimes the Greek Church and sometimes the Latin had the advantage. In 1850, at the suggestion of Turkey, a mixed commission was appointed to consider the dispute and decide upon it.

"The Porte, as the Turkish Government is officially designated, issued in March, 1852, a decree that the Greek Church should be confirmed in the rights it formerly held, and that the Latins could not claim exclusive possession of any of the holy places. It allowed them to have a key to the

Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem, and to certain other buildings of minor importance.

"If you want to know how the Christian churches are now quarrelling about the sacred places in the East, read Chapters XXII., XXIII., and XXIV. of 'The Boy Travellers in Egypt and the Holy Land.'

"France accepted the decision, though she did not like it; Russia continued to demand that the Latin monks should be deprived of their keys, and finally insisted that the Czar should have a protectorate over the Greek Christians in Turkey. The Porte said such a protectorate would interfere with its own authority, and refused the demand; thereupon the Russian Minister left Constantinople on the 21st of May, 1853.

"This may be considered the beginning of the war between Russia and Turkey, though there was no fighting for several months.

"France came to the aid of Turkey; England came to the aid of Turkey and France. Representatives of England, France, Austria, and Prussia met at Vienna and agreed upon a note which Russia accepted; Turkey demanded modifications which Russia refused; Turkey declared war against Russia on the 5th of October, and Russia declared war against Turkey on the 1st of November.

"A Turkish fleet of twelve ships was lying at Sinope, a port on the southern shore of the Black Sea. On the 30th of November the Russians sent a fleet of eleven ships from Sebastopol which destroyed the Turkish fleet, all except one ship that carried the news to Constantinople. Then the allied fleets of the French and English entered the Black Sea, and the war began in dead earnest. For some months it was confined to the Danubian principalities and to the Baltic Sea; on the 14th of September, 1854, the allied army landed at Eupatoria, in the Crimea, and the extent of their preparations will be understood when it is known that forty thousand men, with a large number of horses and a full equipment of artillery, were put on shore in a single day!

"On the 20th of September the battle of the Alma was fought by fifty-seven thousand English, French, and Turkish troops, against fifty thousand Russians. The battle began at noon, and four hours later the Russians were defeated and in full retreat. The Russians lost five thousand men, and the Allies about three thousand four hundred; the Allies might have marched into Sebastopol with very little resistance, but their commanders were uncertain as to the number of troops defending the city, and hesitated to make the attempt.

"On the 17th of October the siege began. A grand attack was made by the Allies, but was unsuccessful, and eight days later the famous charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava was made. On the 5th of November the Russians attacked the Allies at Inkermann, and were repulsed. The battle of Inkermann was fought in a fog by forty thousand Russians against fifteen thousand French and English. The latter had the advantage of position and weapons; the Allies frankly credited the Russian troops with the greatest bravery in returning repeatedly to the attack as their battalions were mowed down by the steady fire of the defenders.

"During the winter the siege was pushed, and the allied army suffered greatly from cholera, cold, and sickness. The siege continued during spring and summer; the Allies made an unsuccessful attack on the Malakoff and Redan forts on the 18th of June, 1855, and all through the long months there were daily conflicts between the opposing armies.

"The Russians sunk several ships of their fleet in the harbor of Sebastopol soon after the battle of the Alma, but retained others for possible future use. On the 8th of September the French captured the Malakoff fort, the English at the same time making an unsuccessful attack on the Redan. The Russians evacuated Sebastopol during the night, crossing over to the north side of the harbor, burning or sinking their fleet, and destroying their military stores.

"This gave the Allies the possession of the city, and though the two armies confronted each other for some time, there was never any serious fighting after that. Other warlike operations were conducted along the Russian shores of the Black Sea. Proposals of peace were made by Austria with the consent of the Allies, and finally, on the 30th of March, 1856, the treaty of peace was signed at Paris. The Allies had begun the destruction of the docks at Sebastopol, but so extensive were those works that with all the engineering skill at their command they were not through with it until July 9th, when they evacuated the Crimea."

"Will that do for a condensed history of the Crimean War?" said Frank, as the result of their labors was submitted to the Doctor.

"It will do very well," was the reply. "Perhaps some of your schoolmates who are not fond of history may be inclined to skip, but I think the majority of readers will thank you for giving it."

"Perhaps they would like a few words on the war between Turkey and Russia in 1877-78," said Fred. "If you think so we will give it."

Doctor Bronson approved the suggestion, and an hour or two later Fred submitted the following:

"In 1875 and '76 there were disturbances in Constantinople and in several provinces of European Turkey. The Sultan of Turkey was deposed, and either committed suicide or was murdered. There were revolts in Herzegovina and Bulgaria, and the troops sent to suppress these revolts committed many outrages. Servia and Montenegro made war upon Turkey on behalf of the Christian subjects of the Porte; Russia came to the support of Servia and Montenegro. There was a vast deal of diplomacy, in which all the great powers joined, and on several occasions it looked as though half of Europe would be involved in the difficulty.

"Turkey and Servia made peace on March 1, 1877. The principal nations of Europe held a conference, and made proposals for reforms in

VIEW OF SEBASTOPOL.

Turkey which the Porte rejected. Russia declared war against Turkey April 24, 1877, and immediately entered the Turkish dominions in Roumania and Armenia.

"The war lasted until March 3, 1878, when a treaty of peace was made at San Stefano, near Constantinople. Many battles were fought during the war, and the losses were heavy on both sides; the severest battles were those of the Shipka Pass and of Plevna. The fortune of war fluctuated, but on the whole the successes were on the side of Russia, and

RUINS OF THE MALAKOFF, SEBASTOPOL.

her armies finally stood ready to enter Constantinople. Her losses were said to have been fully one hundred thousand men, and the cost of the war was six hundred million dollars.

"After the war came the Berlin Conference of 1878, which gave independence to some of the countries formerly controlled by Turkey, made new conditions for the government of others, regulated the boundaries between Russia and Turkey, giving the former several ports and districts of importance, and required the Porte to guarantee certain rights and privileges to her Christian subjects. England interfered, as she generally does, to prevent Russia from reaping the full advantages she expected from the war, and altogether the enterprise was a very costly one for the government of the Czar."

"A very good summary of the war," said the Doctor. "You have disposed of an important phase of the 'Eastern Question' with a brevity that some of the diplomatic writers would do well to study. You might add that for two centuries Russia has had her eye on Constantinople, and is determined to possess it; England is equally determined that Russia shall not have her way, and the other powers are more in accord with England than with Russia."

The steamer entered the harbor of Sebastopol, and made fast to the dock. Frank and Fred observed that the port was admirably defended by forts at the entrance. Doctor Bronson told them the forts which stood there in 1854 were destroyed by the Allies after the capture of the city, but they have since been rebuilt and made stronger than ever before.

As they neared the forts that guard the entrance of the harbor, a Russian officer who was familiar with the locality pointed out several objects of interest. "On the left," said he, "that pyramid on the low hill indicates the battle-field of Inkermann; still farther on the left is the valley of the Alma; those white dots near the Inkermann pyramid mark the site of the British cemetery, and close by it is the French one. In front of you and beyond the harbor is the mound of the Malakoff, and beyond it are the Redan and the Mamelon Yert. Those heaps of ruins are the walls of the Marine Barracks and Arsenal; they are rapidly disappearing in the restoration that has been going on since 1871, and in a few years we hope to have them entirely removed."

There was quite a crowd at the landing-place, variously composed of officers, soldiers, and mujiks; the former for duty or curiosity, and the mujiks scenting a possible job. Our friends proceeded directly to the hotel, which was only two or three hundred yards from the landing-place. As soon as they had selected their rooms and arranged the terms for their accommodation, Dr. Bronson told the proprietor that they wished a carriage and a guide as soon as possible. A messenger was despatched at once for the carriage, while the guide was summoned from another part of the house.

"I suppose you will go first to the cemetery," said the host of the establishment.

"We don't care for the cemetery," said the Doctor, "until we have seen everything else. If there is any time remaining, we may have a look at it.""Then you are Americans," exclaimed the landlord. "All Englishmen coming here want to go first to the cemetery as they have friends buried there, but Americans never care for it."

Doctor Bronson smiled at this mode of ascertaining the nationality of English-speaking visitors, and said it had been remarked by previous visitors to Sebastopol.

When the guide and carriage were ready, the party started on its round of visits. From the bluff they looked down upon the harbor, which was lined with workshops and bordered in places by a railway track, arranged

RUSSIAN CARPENTERS AT WORK.

COSSACKS AND CHASSEURS.

Crimean war taught her the necessity of railways, and she has since acted upon the lesson for which she paid such a high price.

Frank and Fred climbed quickly to the top of the Malakoff, and the Doctor followed demurely behind them. The lines which marked the saps and mines of the Allies have been nearly all filled up, and the traces of the war are being obliterated. From the top of the casemate the guide pointed out many places of interest. With considerable animation he told how for twenty years after the war the ruins of the city remained pretty nearly as they were when the Allies evacuated the Crimea; whole squares of what had once been fine buildings were nothing but heaps of stones. But now Sebastopol is being restored to her former beauty, and every year large areas of the ruins are making way for new structures.

"Sebastopol will be a greater city than it ever was before," said Doctor Bronson, as they stood on the Malakoff. "It was a naval port before, and not a commercial one; now it is both naval and commercial, and by glancing at the map of the Black Sea you can perceive the advantages of its position."

Then the guide pointed out the new dock-yards and barracks, the warehouses and docks of "The Russian Company of Navigation and Commerce," the railway-station close to the shore of the harbor, and the blocks of new buildings which were under construction.

Then he showed the positions of Inkermann, the Tchernaya, and the Redan, and indicated the lines of the French and English attack. When the scene had been sufficiently studied, the party returned to the carriage and continued their ride. The driver was instructed to go to Balaklava, stopping on the way to show them the spot which history has made famous for the charge of the Light Brigade.

As they passed along the level plateau or plain of Sebastopol, they saw everywhere traces of the camps of the armies that besieged the city. The guide showed the route of the railway which connected the harbor of Balaklava with the camp, the wagon-roads built by the Allies, the redoubts that served as defences against attacks in the rear, and the ridges of earth which marked the positions of the huts where officers and soldiers had their quarters during the terrible winter of 1854-55.

Naturally the conversation turned upon the charge of the Light Brigade. One of the youths asked the Doctor what he thought of it.

"There has been a great deal of controversy about the matter," was the reply. "It is difficult to arrive at the exact facts, as Captain Nolan, who brought the order for the cavalry to advance, was killed in the charge. Comparing the statements of all concerned in issuing, receiving, and executing the order, it is evident that the order was 'blundered' somewhere. This was the understanding immediately after the controversy; Tennyson's poem on the affair originally contained the following:

"'Then up came an order

Which some one had blundered.’

"The commander of the French army justly remarked of this charge, 'C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre' ("It is magnificent, but it is not war"). Twelve thousand Russians had attacked the English with the intention of taking Balaklava and its port, but they were compelled to

BRITISH SOLDIERS IN CAMP.

retire to the end of the valley. They had re-formed, with their artillery in front, and infantry and cavalry immediately behind. By the misunderstanding of the order of Lord Raglan, the British commander-in-chief. Lord Lucan, who commanded the cavalry division, ordered Lord Cardigan to charge with his light cavalry.

"In other words the light cavalry, six hundred and seventy strong, were to attack twelve thousand Russians with thirty cannon on their front. The charge was over a plain a mile and a half long, and the Russians had a battery of field artillery on each side of the valley within supporting distance of that at the end. Consequently there is an excellent description of the scene in Tennyson's lines,

" 'Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them,

Volley'd and thunder'd.'

"The charge was made very reluctantly by Lord Cardigan, as you may well believe, but he had no alternative other than to obey the order of his superior. There was never a more brilliant charge. The column advanced at a trot for the first half of the distance, and afterwards at a gallop; the Russian cannon made huge gaps in the ranks, but they were closed up, and on and on swept the heroes, up to and beyond the Russian cannon—

" 'Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army, while

All the world wonder'd:

Plunged in the battery-smoke,

Right thro' the line they broke;

Cossack and Russian

Reel'd from the sabre-stroke

Shatter'd and sunder'd.

Then they rode back, but not,

Not the six hundred.'

"According to one authority, out of six hundred and seventy British horsemen that went to the charge, only one hundred and ninety-eight returned. Another authority gives the total loss in killed, wounded, and captured as four hundred and twenty-six. Five hundred and twenty horses were lost in the charge."

"Here is Balaklava," said the guide, as the carriage stopped at a turn in the road overlooking the valley.

Our friends stepped from the vehicle and sat down upon a little mound of earth, where they tried to picture the scene of the dreadful October day of 1854. Of the actors and spectators of that event very few are now alive.

The Doctor completed the recitation of the poem, and his youthful listeners felt down to the depths of their hearts the full force of the closing lines:

"Honor the brave and bold,

Long shall the tale be told,

Yea, when our babes are old,

How they rode onward.

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wonder'd.

Honor the charge they made!

Honor the Light Brigade!

Noble six hundred!"

From the battle-field the party went to the village of Balaklava and hired a row-boat, in which they paddled about the little, landlocked harbor,

A BROKEN TARANTASSE.

and out through its entrance till they danced on the blue waters of the Euxine Sea. Frank and Fred could hardly believe that the narrow basin once contained a hundred and fifty English and French ships; it seemed that there was hardly room for a third of that number.

On their return journey they passed a party with a broken tarantasse. They stopped a moment and offered any assistance in their power, but finding they could be of no use they did not tarry long. When they reached Sebastopol the sun had gone down in the west, and the stars

THE BOSPORUS.

twinkled in the clear sky that domed the Crimea. The next morning they rambled about the harbor and docks of the city, and a little past noon were steaming away in the direction of Odessa.

A day was spent in this prosperous city, which has a population of nearly two hundred thousand, on a spot where at the end of the last century there was only a Tartar village of a dozen houses, and a small fortress of Turkish construction. Odessa has an extensive commerce, and the ships of all nations lie at its wharves. Its greatest export trade is in wheat, which goes to all parts of the Mediterranean, and also to England. The Black Sea wheat formerly found a market in America, but all that has been changed in recent years through the development of the wheat-growing interest in our Western States and on the Pacific Coast.

Immediately on their arrival they sent their passports to receive the proper permission for leaving the country. Everything was arranged in the course of the day, and on the following afternoon they embarked on a steamer that carried them to Constantinople.

The second morning after leaving Odessa they entered the Bosporus, the strait which separates Europe and Asia, and connects the waters of the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmora and the Mediterranean. As they looked at the beautiful panorama, which shifted its scene with every pulsation of the steamer's engine, Frank said he had had a dream during the night which was so curious that he wanted to tell it.

"What was it?" the Doctor asked.

"I dreamed," said Frank, "that England and Russia had become friends, and made up their minds to work together for the supremacy of the world. England had supplied the money for completing the railway to India; she had built a tunnel under the British Channel, and it was possible to ride from London to Calcutta or Bombay without changing cars. The Turks had been expelled from Europe; European Turkey was governed by a Russian prince married to an English princess; the principality had its capital at Constantinople, and a guarantee of neutrality like that of Belgium, to which all the great powers had assented. War and commercial ships of all nations could pass the Bosporus and Dardanelles as freely as through the Suez Canal, and the restrictions made by the treaty of Paris were entirely removed. England and Russia had formed an offensive and defensive alliance, and all the rest of the world had been ordered to keep the peace. And they were keeping it, too, as they dreaded the combined power of England's money and Russia's men."

"A very pretty fancy!" said the Doctor. "What a pity it was all a dream!"

THE END.