The History of the Standard Oil Company/Volume 1/Chapter 2

CHAPTER TWO

THE RISE OF THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY

THE chief refining competitor of Oil Creek in 1872 was Cleveland, Ohio. Since 1869 that city had done annually more refining than any other place in the country. Strung along the banks of Walworth and Kingsbury Runs, the creeks to which the city frequently banishes her heavy and evil-smelling burdens, there had been since the early sixties from twenty to thirty oil refineries. Why they were there, more than 200 miles from the spot where the oil was taken from the earth, a glance at a map of the railroads of the time will show: By rail and water Cleveland commanded the entire Western market. It had two trunk lines running to New York, both eager for oil traffic, and by Lake Erie and the canal it had for a large part of the year a splendid cheap waterway. Thus, at the opening of the oil business, Cleveland was destined by geographical position to be a refining center.

Men saw it, and hastened to take advantage of the opportunity. There was grave risk. The oil supply might not hold out. As yet there was no certain market for refined oil. But a sure result was not what drew people into the oil business in the early sixties. Fortune was running fleet-footed across the country, and at her garment men clutched. They loved the chase almost as they did success, and so many a man in Cleveland tried his luck in an oil refinery, as hundreds on Oil Creek were trying it in an oil lease. By 1865 there were thirty refineries in the town, with a capital of about a million and a half dollars and a daily capacity of some 2,000 barrels. The works multiplied rapidly. The report of the Cleveland Board of Trade for 1866 gives the number of plants at the end of that year as fifty, and it dilates eloquently on the advantages of Cleveland as a refining point over even Pittsburg, to that time supposed to be the natural centre for the business. If the railroad and lake transportation men would but adopt as liberal a policy toward the oil freights of Cleveland as the Pennsylvania Railroad was adopting toward that of Pittsburg, aided by her natural advantages the town was bound to become the greatest oil refining centre in the United States. By 1868 the Board of Trade reported joyfully that Cleveland was receiving within 300,000 barrels as much oil as Pittsburg. In 1869 she surpassed all competitors. "Cleveland now claims the leading position among the manufacturers of petroleum with a very reasonable prospect of holding that rank for some time to come," commented the Board of Trade report. "Each year has seen greater consolidation of capital, greater energy and success in prosecuting the business, and, notwithstanding some disastrous fires, a stronger determination to establish an immovable reputation for the quantity and quality of this most important product. The total capital invested in this business is not less than four millions of dollars and the total product of the year would not fall short of fifteen millions."

Among the many young men of Cleveland who, from the start, had an eye on the oil-refining business and had begun to take an active part in its development as soon as it was demonstrated that there was a reasonable hope of its being permanent, was a young firm of produce commission merchants. Both members of this firm were keen business men, and one of them had remarkable commercial vision—a genius for seeing the possibilities in material things. This man's name was Rockefeller—John D. Rockefeller. He was but twenty-three years old when he first went into the oil business, but he had already got his feet firmly on the business ladder, and had got them there by his own efforts. The habit of driving good bargains and of saving money had started him. He himself once told how he learned these lessons so useful in money-making, in one of his frequent Sunday-school talks to young men on success in business. The value of a good bargain he learned in buying cord-wood for his father: "I knew what a cord of good solid beech and maple wood was. My father told me to select only the solid wood and the straight wood and not to put any limbs in it or any punky wood. That was a good training for me. I did not need any father to tell me or anybody else how many feet it took to make a cord of wood."

And here is how he learned the value of investing money: "Among the early experiences that were helpful to me that I recollect with pleasure was one in working a few days for a neighbour in digging potatoes—a very enterprising, thrifty farmer, who could dig a great many potatoes. I was a boy of perhaps thirteen or fourteen years of age, and it kept me very busy from morning until night. It was a ten-hour day. And as I was saving these little sums I soon learned that I could get as much interest for fifty dollars loaned at seven per cent.—the legal rate in the state of New York at that time for a year—as I could earn by digging potatoes for 100 days. The impression was gaining ground with me that it was a

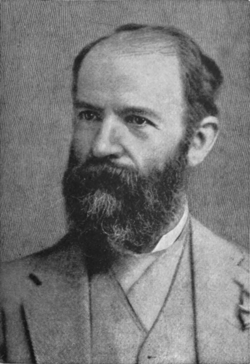

JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IN 1872

good thing to let the money be my slave and not make myself a slave to money." Here we have the foundation principles of a great financial career.

When young Rockefeller was thirteen years old, his father moved from the farm in Central New York, where the boy had been born (July 8, 1839), to a farm near Cleveland, Ohio. He went to school in Cleveland for three years. In 1855 it became necessary for him to earn his own living. It was a hard year in the West and the boy walked the streets for days looking for work. He was about to give it up and go to the country when, to quote the story as Mr. Rockefeller once told it to his Cleveland Sunday-school, "As good fortune would have it I went down to the dock and made one more application, and I was told that if I would come in after dinner—our noon-day meal was dinner in those days—they would see if I could come to work for them. I went down after dinner and I got the position, and I was permitted to remain in the city." The position, that of a clerk and bookkeeper, was not lucrative. According to a small ledger which has figured frequently in Mr. Rockefeller's religious instructions, he earned from September 26, 1855, to January, 1856, fifty dollars. "Out of that," Mr. Rockefeller told the young men of his Sunday-school class, "I paid my washerwoman and the lady I boarded with, and I saved a little money to put away."

He proved an admirable accountant—one of the early-and-late sort, who saw everything, forgot nothing and never talked. In 1856 his salary was raised to twenty-five dollars a month, and he went on always "saving a little money to put away." In 1858 came a chance to invest his savings. Among his acquaintances was a young Englishman, M. B. Clark. Older by twelve years than Rockefeller he had left a hard life in England when he was twenty to seek fortune in America. He had landed in Boston in 1847, without a penny or a friend, and it had taken three months for him to earn money to get to Ohio. Here he had taken the first job at hand, as man-of-all-work, wood-chopper, teamster. He had found his way to Cleveland, had become a valuable man in the houses where he was employed, had gone to school at nights, had saved money. They were two of a kind, Clark and Rockefeller, and in 1858 they pooled their earnings and started a produce com-

Bobr Prank, cabinet maker, bds 17 Johnson

Rochert Conrad, h 175 St Clair

Rock John, bar keeper, bds 11 Public Square

Rockefeller John D., book-keeper, h 35 Cedar

Rockefeller William, physician, h 35 Cedar av

Rockett Morris, rectifier, h 182 St Clair

Rockwell Edward, Sec C. & P. R. R, bds Weddell House

Fragment of a page in the city directory of Cleveland, Ohio, for 1857. This is the first year in which the name John D. Rockefeller appears in the directory. The same entry is made in 1858. The next year, 1859, Mr. Rockefeller is entered as a member of the firm of Clark and Rockefeller.

mission business on the Cleveland docks. The venture succeeded. Local historians credit Clark and Rockefeller with doing a business of $450,000 the first year. The war came on, and as neither partner went to the front, they had full chance to take advantage of the opportunity for produce business a great army gives. A greater chance than furnishing army supplies, lucrative as most people found that, was in the oil business (so Clark and Rockefeller began to think), and in 1862, when an Englishman of ability and energy, one Samuel Andrews, asked them to back him in starting a refinery, they put in $4,000 and promised to give more if necessary. Now Andrews was a mechanical genius. He devised new processes made a better and better quality of oil, got larger and larger percentages of refined from his crude. The little refinery grew big, and Clark and Rockefeller soon had $100,000 or more in it. In the meantime Cleveland was growing as a refining centre. The business which in 1860 had been a gamble was by 1865 one of the most promising industries of the town. It was but the beginning—so Mr. Rockefeller thought—and in that year he sold out his share of the commission business and put his money into the oil firm of Rockefeller and Andrews.

In the new firm Andrews attended to the manufacturing. The pushing of the business, the buying and the selling, fell to Rockefeller. From the start his effect was tremendous. He had the frugal man's hatred of waste and disorder, of middlemen and unnecessary manipulation, and he began a vigorous elimination of these from his business. The residuum that other refineries let run into the ground, he sold. Old iron found its way to the junk shop. He bought his oil directly from the wells. He made his own barrels. He watched and saved and contrived. The ability with which he made the smallest bargain furnishes topics to Cleveland story-tellers to-day. Low-voiced, soft-footed, humble, knowing every point in every man's business, he never tired until he got his wares at the lowest possible figure. "John always got the best of the bargain," old men tell you in Cleveland to-day, and they wince though they laugh in telling it. "Smooth," "a savy fellow," is their description of him. To drive a good bargain was the joy of his life. "The only time I ever saw John Rockefeller enthusiastic," a man told the writer once, "was when a report came in from the creek that his buyer had secured a cargo of oil at a figure much below the market price. He bounded from his chair with a shout of joy, danced up and down, hugged me, threw up his hat, acted so like a madman that I have never forgotten it."

He could borrow as well as bargain. The firm's capital was limited; growing as they were, they often needed money, and had none. Borrow they must. Rarely if ever did Mr. Rockefeller fail. There is a story handed down in Cleveland from the days of Clark and Rockefeller, produce merchants, which is illustrative of his methods. One day a well-known and rich business man stepped into the office and asked for Mr. Rockefeller. He was out, and Clark met the visitor. "Mr. Clark," he said, "you may tell Mr. Rockefeller, when he comes in, that I think I can use the $10,000 he wants to invest with me for your firm. I have thought it all over."

"Good God!" cried Clark, "we don't want to invest $10,000. John is out right now trying to borrow $5,000 for us."

It turned out that to prepare him for a proposition to borrow $5,000 Mr. Rockefeller had told the gentleman that he and Clark wanted to invest $10,000!

"And the joke of it is," said Clark, who used to tell the story, "John got the $5,000 even after I had let the cat out of the bag. Oh, he was the greatest borrower you ever saw!"

These qualities told. The firm grew as rapidly as the oil business of the town, and started a second refinery—William A. Rockefeller and Company. They took in a partner, H. M. Flagler, and opened a house in New York for selling oil. Of all these concerns John D. Rockefeller was the head. Finally, in June, 1870, five years after he became an active partner in the refining business, Mr. Rockefeller combined all his companies into one—the Standard Oil Company. The capital of the new concern was $1,000,000. The parties interested in it were John D. Rockefeller, Henry M. Flagler, Samuel Andrews, Stephen V. Harkness, and William Rockefeller.[1]

The strides the firm of Rockefeller and Andrews made after the former went into it were attributed for three or four years mainly to his extraordinary capacity for bargaining and borrowing. Then its chief competitors began to suspect something. John Rockefeller might get his oil cheaper now and then, they said, but he could not do it often. He might make close contracts for which they had neither the patience nor the stomach. He might have an unusual mechanical and practical genius in his partner. But these things could not

Map of Northwestern Pennsylvania, showing the relation of the Oil Regions to the railroads in 1859, when oil was "discovered."

explain all. They believed they bought, on the whole, almost as cheaply as he, and they knew they made as good oil and with as great, or nearly as great, economy. He could sell at no better price than they. Where was his advantage? There was but one place where it could be, and that was in transportation. He must be getting better rates from the railroads than they were. In 1868 or 1869 a member of a rival firm long in the business, which had been prosperous from the start, and which prided itself on its methods, its economy and its energy, Alexander, Scofield and Company, went to the Atlantic and Great Western road, then under the Erie management, and complained. "You are giving others better rates than you are us," said Mr. Alexander, the representative of the firm. "We cannot compete if you do that." The railroad agent did not attempt to deny it—he simply agreed to give Mr. Alexander a rebate also. The arrangement was interesting. Mr. Alexander was to pay the open, or regular, rate on oil from the Oil Regions to Cleveland, which was then forty cents a barrel. At the end of each month he was to send to the railroad vouchers for the amount of oil shipped and paid for at forty cents, and was to get back from the railroad, in money, fifteen cents on each barrel. This concession applied only to oil brought from the wells. He was never able to get a rebate on oil shipped eastward.[2] According to Mr. Alexander, the Atlantic and Great Western gave the rebates on oil from the Oil Regions to Cleveland up to 1871 and the system was then discontinued. Late in 1871, however, the firm for the first time got a rebate on the Lake Shore road on oil brought from the field.

Another Cleveland man, W. H. Doane, engaged in shipping crude oil, began to suspect about the same time as Mr. Alexander that the Standard was receiving rebates. Now Mr. Doane had always been opposed to the "drawback business," but it was impossible for him to supply his customers with crude oil at as low a rate as the Standard paid if it received a rebate and he did not, and when it was first generally rumoured in Cleveland that the railroads were favouring Mr. Rockefeller he went to see the agent of the road. "I told him I did not want any drawback, unless others were getting it; I wanted it if they were getting it, and he gave me at that time ten cents drawback." This arrangement Mr. Doane said had lasted but a short time. At the date he was speaking—the spring of 1872—he had had no drawback for two years.

A still more important bit of testimony as to the time when rebates first began to be given to the Cleveland refiners and as to who first got them and why, is contained in an affidavit made in 1880 by the very man who made the discrimination.[3] This man was General J. H. Devereux, who in 1868 succeeded Amasa Stone as vice-president of the Lake Shore Railroad. General Devereux said that his experience with the oil traffic had begun with his connection with the Lake Shore; that the only written memoranda concerning oil which he found in his office on entering his new position was a book in which it was stated that the representatives of the twenty-five oil-refining firms in Cleveland had agreed to pay a cent a gallon on crude oil removed from the Oil Regions. General Devereux says that he soon found there was a deal of trouble in store for him over oil freight. The competition between the twenty-five firms was close, the Pennsylvania was "claiming a patent right" on the transportation of oil and was putting forth every effort to make Pittsburg and Philadelphia the chief refining centres. Oil Creek was boasting that it was going to be the future refining point for the world. All of this looked bad for what General Devereux speaks of as the "then very limited refining capacity of Cleveland." This remark shows how new he was to the business, for, as we have already seen, Cleveland in 1868 had anything but a limited refining capacity. Between three and four million dollars were invested in oil refineries, and the town was receiving within 35,000 barrels of as much oil as New York City, and within 300,000 as much as Pittsburg, and it was boasting that the next year it would outstrip these competitors, which, as a matter of fact, it did.

The natural point for General Devereux to consider, of course, was whether he could meet the rates the Pennsylvania were giving and increase the oil freight for the Lake Shore. The road had a branch running to Franklin, Pennsylvania, within a few miles of Oil City. This he completed, and then, as he says in his affidavit, "a sharper contest than ever was produced growing out of the opposition of the Pennsylvania Railroad in competition. Such rates and arrangements were made by the Pennsylvania Railroad that it was publicly proclaimed in the public print in Oil City, Titusville and other places that Cleveland was to be wiped out as a refining centre as with a sponge." General Devereux goes on to say that all the refiners of the town, without exception, came to him in alarm, and expressed their fears that they would have either to abandon their business there or move to Titusville or other points in the Oil Regions; that the only exception to this decision was that offered by Rockefeller, Andrews and Flagler, who, on his assurance that the Lake Shore Railroad could and would handle oil as cheaply as the Pennsylvania Company, proposed to stand their ground at Cleveland and fight it out on that line. And so General Devereux gave the Standard the rebate on the rate which Amasa Stone had made with all the refiners. Why he should not have quieted the fears of the twenty-four or twenty-five other refiners by lowering their rate, too, does not appear in the affidavit. At all events the rebate had come, and, as we have seen, it soon was suspected and others went after it, and in some cases got it. But the rebate seems to have been granted generally only on oil brought from the Oil Regions. Mr. Alexander claims he was never able to get his rate lowered on his Eastern shipments. The railroad took the position with him that if he could ship as much oil as the Standard he could have as low a rate, but not otherwise. Now in 1870 the Standard Oil Company had a daily capacity of about 1,500 barrels of crude. The refinery was the largest in the town, though it had some close competitors. Nevertheless on the strength of its large capacity it received the special favour. It was a plausible way to get around the theory generally held then, as now, though not so definitely crystallised into law, that the railroad being a common carrier had no right to discriminate between its patrons. It remained to be seen whether the practice would be accepted by Mr. Rockefeller's competitors without a contest, or, if contested, would be supported by the law.

What the Standard's rebate on Eastern shipments was in 1870 it is impossible to say. Mr. Alexander says he was never able to get a rate lower than $1.33 a barrel by rail, and that it was commonly believed in Cleveland that the Standard had a rate of ninety cents. Mr. Flagler, however, the only member of the firm who has been examined under oath on that point, showed, by presenting the contract of the Standard Oil Company with the Lake Shore road in 1870, that the rates varied during the year from $1.40 to $1.20 and $1.60, according to the season. When Mr. Flagler was asked if there was no drawback or rebate on this rate he answered, "None whatever."

It would seem from the above as if the one man in the Cleveland oil trade in 1870 who ought to have been satisfied was Mr. Rockefeller. His was the largest firm in the largest refining centre of the country; that is, of the 10,000 to 12,000 daily capacity divided among the twenty-five or twenty-six refiners of Cleveland he controlled 1,500 barrels. Not only was Cleveland the largest refining centre in the country, it was gaining rapidly, for where in 1868 it shipped 776,356 barrels of refined oil, in 1869 it shipped 923,933, in 1870 1,459,500, and in 1871 1,640,499.[4] Not only did Mr. Rockefeller control the largest firm in this most prosperous centre of a prosperous business, he controlled one of amazing efficiency. The combination, in 1870, of the various companies with which he was connected had brought together a group of remarkable men. Samuel Andrews, by all accounts, was the ablest mechanical superintendent in Cleveland. William Rockefeller, the brother of John D. Rockefeller, was not only an energetic and intelligent business man, he was a man whom people liked. He was open-hearted, jolly, a good story-teller, a man who knew and liked a good horse-not too pious, as some of John's business associates thought him, not a man to suspect or fear, as many a man did John. Old oil men will tell you on the creek to-day how much they liked him in the days when he used to come to Oil City buying oil for the Cleveland firm. The personal quality of William Rockefeller was, and always has been, a strong asset of the Standard Oil Company. Probably the strongest man in the firm after John D. Rockefeller was Henry M. Flagler. He was, like the others, a young man, and one who, like the head of the firm, had the passion for money, and in a hard self-supporting experience, begun when but a boy, had learned, as well as his chief, some of the principles of making it. He was untiring in his efforts to increase the business, quick to see an advantage, as quick to take it. He had no scruples to make him hesitate over the ethical quality of a contract which was advantageous. Success, that is, making money, was its own justification. He was not a secretive man, like John D. Rockefeller, not a dreamer, but he could keep his mouth shut when necessary and he knew the worth of a financial dream when it was laid before him. It must have been evident to every business man who came in contact with the young Standard Oil Company that it would go far. The firm itself must have known it would go far. Indeed nothing could have stopped the Standard Oil Company in 1870—the oil business being what it was—but an entire change in the nature of the members of the firm, and they were not the kind of material which changes.

With such a set of associates, with his organisation complete from his buyers on the creek to his exporting agent in New York, with the transportation advantages which none of his competitors had had the daring or the persuasive power to get, certainly Mr. Rockefeller should have been satisfied in 1870. But Mr. Rockefeller was far from satisfied. He was a brooding, cautious, secretive man, seeing all the possible dangers as well as all the possible opportunities in things, and he studied, as a player at chess, all the possible combinations which might imperil his supremacy. These twenty-five Cleveland rivals of his—how could he at once and forever put them out of the game? He and his partners had somehow conceived a great idea—the advantages of combination. What might they not do if they could buy out and absorb the big refineries now competing with them in Cleveland? The possibilities of the idea grew as they discussed it. Finally they began tentatively to sound some of their rivals. But there were other rivals than these at home. There were the creek refiners! They were there at the mouth of the wells. What might not this geographical advantage do in time? Refining was going on there on an increasing scale; the capacity of the Oil Regions had indeed risen to nearly 10,000 barrels a day—equal to that of New York, exceeding that of Pittsburg by nearly 4,000 barrels, and almost equalling that of Cleveland. The men of the oil country loudly declared that they meant to refine for the world. They boasted of an oil kingdom which eventually should handle the entire business and compel Cleveland and Pittsburg either to abandon their works or bring them to the oil country. In this boastful ambition they were encouraged particularly by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which naturally handled the largest percentage of the oil. How long could the Standard Oil Company stand against this competition?

There was another interest as deeply concerned as Mr. Rockefeller in preserving Cleveland's supremacy as a refining centre, and this was the Lake Shore and New York Central Railroads. Let the bulk of refining be done in the Oil Regions and these roads were in danger of losing a profitable branch of business. This situation in regard to the oil traffic was really more serious now than in 1868 when General Devereux had first given the Standard a rebate. Then it was that the Pennsylvania, through its lusty ally the Empire Transportation Company, was making the chief fight to secure a "patent right on oil transportation." The Erie was now becoming as aggressive a competitor. Gould and Fisk had gone into the fight with the vigour and the utter unscrupulousness which characterised all their dealings. They were allying themselves with the Pennsylvania Transportation Company, the only large rival pipe-line system which the Empire had. They were putting up a refinery near Jersey City and they were taking advantage shrewdly of all the speculative features of the new business.

As competition grew between the roads, they grew more reckless in granting rebates, the refiners more insistent in demanding them. By 1871 things had come to such a pass in the business that every refiner suspected his neighbour to be getting better rates than he. The result was that the freight agents were constantly beset for rebates, and that the large shippers were generally getting them on the ground of the quantity of oil they controlled. Indeed it was evident that the

W. G. WARDEN

Secretary of the South Improvement Company.

PETER H. WATSON

President of the South Improvement Company.

CHARLES LOCKHART

A member of the South Improvement Company, and later of the Standard Oil Company. At his death in 1904 the oldest living oil operator.

HENRY M. FLAGLER IN 1882

Active partner of John D. Rockefeller in the oil business since 1867. Officer of the Standard Oil Company since its organization in 1870.

rebate being admitted, the only way in which it could be adjusted with a show of fairness was to grade it according to the size of the shipment.

Under these conditions of competition it was certain that the New York Central system must work if it was to keep its great oil freight, and the general freight agent of the Lake Shore road began to give the question special attention. This man was Peter H. Watson. Mr. Watson was an able patent lawyer who served under the strenuous Stanton as an Assistant-Secretary of War, and served well. After the war he had been made general freight agent of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad, and later president of the branch of that road which ran into the Oil Regions. He had oil interests principally at Franklin, Pennsylvania, and was well known to all oil men. He was a business intimate of Mr. Rockefeller and a warm friend of Horace F. Clark, the son-in-law of W. H. Vanderbilt, at that time president of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad. As the Standard Oil Company was the largest shipper in Cleveland and had already received the special favour from the Lake Shore which General Devereux describes, it was natural that Mr. Watson should consult frequently with Mr. Rockefeller on the question of holding and increasing his oil freight. It was equally natural, too, that Mr. Rockefeller should use his influence with Mr. Watson to strengthen the theory so important to his rapid growth—the theory that the biggest shipper should have the best rate.

Two other towns shared Cleveland's fear of the rise of the Oil Regions as a refining centre, and they were Pittsburg and Philadelphia, and Mr. Rockefeller and Mr. Watson found in certain refiners of these places a strong sympathy with any plan which looked to holding the region in check. But while the menace in their geographical positions was the first ground of sympathy between these gentlemen, something more than local troubles occupied them. This was the condition of the refining business as a whole. It was unsatisfactory in many particulars. First, it was overdone. The great profits on refined oil and the growing demand for it had naturally caused a great number to rush into its manufacture. There was at this time a refining capacity of three barrels to every one produced. To be sure, few if any of these plants expected to run the year around. Then, as to-day, there were nearly always some stills in even the most prosperous works shut down. But after making a fair allowance for this fact there was still a much larger amount of refining actually done than the market demanded. The result was that the price of refined oil was steadily falling. Where Mr. Rockefeller had received on an average 58¾ cents a gallon for the oil he exported in 1865, the year he went into business, in 1870 he received but 26⅜ cents. In 1865 he had a margin of forty-three cents, out of which to pay for transportation, manufacturing, barrelling and marketing and to make his profits. In 1870 he had but 17⅛ cents with which to do all this. To be sure his expenses had fallen enormously between 1865 and 1870, but so had his profits. The multiplication of refiners with the intense competition threatened to cut them down still lower. Naturally Mr. Rockefeller and his friends looked with dismay on this lowering of profits through gaining competition.

Another anxiety of the American refiners was the condition of the export trade. Oil had risen to fourth place in the exports of the United States in the twelve years since its discovery, and every year larger quantities were consumed abroad, but it was crude oil, not refined, which the foreigners were beginning to demand; that is, they had found they could import crude, refine it at home, and sell it cheaper than they could buy American refined. France, to encourage her home refineries, had even put a tax on American refined.

In the fall of 1871, while Mr. Rockefeller and his friends were occupied with all these questions, certain Pennsylvania refiners, it is not too certain who, brought to them a remarkable scheme, the gist of which was to bring together secretly a large enough body of refiners and shippers to persuade all the railroads handling oil to give to the company formed special rebates on its oil, and drawbacks on that of other people. If they could get such rates it was evident that those outside of their combination could not compete with them long and that they would become eventually the only refiners. They could then limit their output to actual demand, and so keep up prices. This done, they could easily persuade the railroads to transport no crude for exportation, so that the foreigners would be forced to buy American refined. They believed that the price of oil thus exported could easily be advanced fifty per cent. The control of the refining interests would also enable them to fix their own price on crude. As they would be the only buyers and sellers, the speculative character of the business would be done away with. In short, the scheme they worked out put the entire oil business in their hands. It looked as simple to put into operation as it was dazzling in its results. Mr. Flagler has sworn that neither he nor Mr. Rockefeller believed in this scheme.[5] But when they found that their friend Peter H. Watson, and various Philadelphia and Pittsburg parties who felt as they did about the oil business, believed in it, they went in and began at once to work up a company—secretly. It was evident that a scheme which aimed at concentrating in the hands of one company the business now operated by scores, and which proposed to effect this consolidation through a practice of the railroads which was contrary to the spirit of their charters, although freely indulged in, must be worked with fine discretion if it ever were to be effective.

The first thing was to get a charter—quietly. At a meeting held in Philadelphia late in the fall of 1871 a friend of one of the gentlemen interested mentioned to him that a certain estate then in liquidation had a charter for sale which gave its owners the right to carry on any kind of business in any country and in any way; that it could be bought for what it would cost to get a charter under the general laws of the state, and that it would be a favour to the heirs to buy it. The opportunity was promptly taken. The name of the charter bought was the "South (often written Southern) Improvement Company." For a beginning it was as good a name as another, since it said nothing.

With this charter in hand Mr. Rockefeller and Mr. Watson and their associates began to seek converts. In order that their great scheme might not be injured by premature public discussion they asked of each person whom they approached a pledge of secrecy. Two forms of the pledges required before anything was revealed were published later. The first of these, which appeared in the New York Tribune, read as follows:

I, A. B., do faithfully promise upon my honour and faith as a gentleman that I will keep secret all transactions which I may have with the corporation known as the South Improvement Company; that, should I fail to complete any bargains with the said company, all the preliminary conversations shall be kept strictly private; and, finally, that I will not disclose the price for which I dispose of my product, or any other facts which may in any way bring to light the internal workings or organisation of the company. All this I do freely promise.

A second, published in a history of the "Southern Improvement Company," ran:

The undersigned pledge their solemn words of honour that they will not communicate to any one without permission of Z (name of director of Southern Improvement Company) any information that he may convey to them, or any of them, in relation to the Southern Improvement Company.

That the promoters met with encouragement is evident from the fact that, when the corporators came together on January 2, 1872, in Philadelphia, for the first time under their charter, and transferred the company to the stockholders, they claimed to represent in one way or another a large part of the refining interest of the country. At this meeting 1,100 shares of the stock of the company, which was divided into 2,000 $100 shares, were subscribed for, and twenty per cent. of their value was paid in. Just who took stock at this meeting the writer has not been able to discover. At the same time a discussion came up as to what refiners were to be allowed to go into the new company. Each of the men represented had friends whom he wanted taken care of, and after considerable discussion it was decided to take in every refinery they could get hold of. This decision was largely due to the railroad men. Mr. Watson had seen them as soon as the plans for the company were formed, and they had all agreed that if they gave the rebates and drawbacks all refineries then existing must be taken in upon the same level. That is, while the incorporators had intended to kill off all but themselves and their friends, the railroads refused to go into a scheme which was going to put anybody out of business—the plan if they went into it must cover the refining trade as it stood. It was enough that it could prevent any one in the future going into the business.

Very soon after this meeting of January 2 the rest of the stock of the South Improvement Company was taken. The complete list of stockholders, with their holdings, was as follows:

William Frew, Philadelphia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10 shares | |

W. P. Logan, Philadelphia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10 shares“ | |

John P. Logan, Philadelphia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10 shares“ | |

Charles Lockhart, Pittsburg . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10 shares“ | |

Richard S. Waring, Pittsburg . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

10 shares“ | |

W. G. Warden, Philadelphia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

475 shares“ | |

O. F. Waring, Pittsburg . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

475 shares“ | |

P. H. Watson, Ashtabula, Ohio . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

100 shares“ | |

H. M. Flagler, Cleveland . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

180 shares“ | |

O. H. Payne, Cleveland . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

180 shares“ | |

William Rockefeller, Cleveland . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

180 shares“ | |

J. A. Bostwick, New York . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

180 shares“ | |

John D. Rockefeller, Cleveland[6] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

180 shares“ | |

| 2,000 shares | ||

Mr. Watson was elected president and W. G. Warden of Philadelphia secretary of the new association. It will be noticed that the largest individual holdings in the company were those of W. G. Warden and O. F. Waring, each of whom had 475 shares. The company most heavily interested in the South Improvement Company was the Standard Oil of Cleveland, J. D. Rockefeller, William Rockefeller and H. M. Flagler, all stockholders of that company, each having 180 shares—540 in the company. O. H. Payne and J. A. Bostwick, who soon after became stockholders in the Standard Oil Company, also had each 180 shares, giving Mr. Rockefeller and his associates 900 shares in all.

It has frequently been stated that the South Improvement Company represented the bulk of the oil-refining interests in the country. The incorporators of the company in approaching the railroads assured them that this was so. As a matter of fact, however, the thirteen gentlemen above named, who were the only ones ever holding stock in the concern, did not control over one-tenth of the refining business of the United States in 1872. That business in the aggregate amounted to a daily capacity of about 45,000 barrels—from 45,000 to 50,000, Mr. Warden put it—and the stockholders of the South Im-provement Company owned a combined capacity of not over 4,600 barrels. In assuring the railroads that they controlled the business, they were dealing with their hopes rather than with facts.

The organisation complete, there remained contracts to be made with the railroads. Three systems were to be interested: The Central, which, by its connection with the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern, ran directly into the Oil Regions; the Erie, allied with the Atlantic and Great Western, with a short line likewise tapping the heart of the region; and the Pennsylvania, with the connections known as the Allegheny Valley and Oil Creek Railroad. The persons to be won over were: W. H. Vanderbilt, of the Central; H. F. Clark, president of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern; Jay Gould, of the Erie; General G. B. McClellan, president of the Atlantic and Great Western; and Tom Scott, of the Pennsylvania. There seems to have been little difficulty in persuading any of these persons to go into the scheme after they had been assured by the leaders that all of the refiners were to be taken in. This was a verbal condition, however, not found in the contracts they signed. This important fact Mr. Warden himself made clear when three months later he was on the witness stand before a committee of Congress appointed to look into the great scheme. "We had considerable discussion with the railroads," Mr. Warden said, "in regard to the matter of rebate on their charges for freight; they did not want to give us a rebate unless it was with the understanding that all the refineries should be brought into the arrangement and placed upon the same level."

A second objection to making a contract with the company came from Mr. Scott of the Pennsylvania road and Mr. Potts of the Empire Transportation Company. The substance of this objection was that the plan took no account of the oil producer—the man to whom the world owed the business. Mr. Scott was strong in his assertion that they could never succeed unless they took care of the producers. Mr. Warden objected strongly to forming a combination with them. "The interests of the producers were in one sense antagonistic to ours: one as the seller and the other as the buyer. We held in argument that the producers were abundantly able to take care of their own branch of the business if they took care of the quantity produced." So strongly did Mr. Scott argue, however, that finally the members of the South Improvement Company yielded, and a draft of an agreement, to be proposed to the producers, was drawn up in lead-pencil; it was Q. You say you made propositions to railroad companies, which they agreed to accept upon the condition that you could include all the refineries?

A. No, sir; I did not say that; I said that was the understanding when we discussed this matter with them; it was no proposition on our part; they discussed it, not in the form of a proposition that the refineries should be all taken in, but it was the intention and resolution of the company from the first that that should be the result; we never had any other purpose in the matter.

Q. In case you could take the refineries all in, the railroads proposed to give you a rebate upon their freight charges?

A. No, sir; it was not put in that form; we were to put the refineries all in upon the same terms; it was the understanding with the railroad companies that we were to have a rebate; there was no rebate given in consideration of our putting the companies all in, but we told them we would do it; the contract with the railroad companies was with us.

Q. But if you did form a company composed of the proprietors of all these refineries, you were to have a rebate upon your freight charges?

A. No; we were to have a rebate anyhow, but were to give all the refineries the privilege of coming in.

Q. You were to have the rebate whether they came in or not?

A. Yes, sir.

***

"What effect were these arrangements to have upon those who did not come into the combination . . . ?" asked the chairman.

"I do not think we ever took that question up," answered Mr. Warden.

THOMAS A. SCOTT

The contract of the South Improvement Company with the Pennsylvania Railroad was signed by Mr. Scott, then vice-president of the road.

WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT

The contract of the South Improvement Company with the New York Central was signed by Mr. Vanderbilt, then vice-president of the road.

JAY GOULD

President of the Erie Railroad in 1872. Signer of the contract with the South Improvement Company.

COMMODORE CORNELIUS VANDERBILT

President of the New York Central Railroad when the contract with the South Improvement Company was signed.

never presented. It seems to have been used principally to quiet Mr. Scott.

The work of persuasion went on swiftly. By the 18th of January the president of the Pennsylvania road, J. Edgar Thompson, had put his signature to the contract, and soon after Mr. Vanderbilt and Mr. Clark signed for the Central system, and Jay Gould and General McClellan for the Erie. The contracts to which these gentlemen put their names fixed gross rates of freight from all common points, as the leading shipping points within the Oil Regions were called, to all the great refining and shipping centres—New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Pittsburg and Cleveland. For example, the open rate on crude to New York was put at $2.56. On this price the South Improvement Company was allowed a rebate of $1.06 for its shipments; but it got not only this rebate, it was given in cash a like amount on each barrel of crude shipped by parties outside the combination.

The open rate from Cleveland to New York was two dollars, and fifty cents of this was turned over to the South Improvement Company, which at the same time received a rebate enabling it to ship for $1.50. Again, an independent refiner in Cleveland paid eighty cents a barrel to get his crude from the Oil Regions to his works, and the railroad sent forty cents of this money to the South Improvement Company. At the same time it cost the Cleveland refiner in the combination but forty cents to get his crude oil. Like drawbacks and rebates were given for all points—Pittsburg, Philadelphia, Boston and Baltimore.

An interesting provision in the contracts was that full way-bills of all petroleum shipped over the roads should each day be sent to the South Improvement Company. This, of course, gave them knowledge of just who was doing business outside of their company—of how much business he was doing, and with whom he was doing it. Not only were they to have full knowledge of the business of all shippers—they were to have access to all books of the railroads.

The parties to the contracts agreed that if anybody appeared in the business offering an equal amount of transportation, and having equal facilities for doing business with the South Improvement Company, the railroads might give them equal advantages in drawbacks and rebates, but to make such a miscarriage of the scheme doubly improbable each railroad was bound to co-operate as "far as it legally might to maintain the business of the South Improvement Company against injury by competition, and lower or raise the gross rates of transportation for such times and to such extent as might be necessary to overcome the competition. The rebates and drawbacks to be varied pari passu with the gross rates."[7]

The reason given by the railroads in the contract for granting these extraordinary privileges was that the "magnitude and extent of the business and operations" purposed to be carried on by the South Improvement Company would greatly promote the interest of the railroads and make it desirable for them to encourage their undertaking. The evident advantages received by the railroad were a regular amount of freight,—the Pennsylvania was to have forty-five per cent., of the East-bound shipments, the Erie and Central each 27½ per cent., while West-bound freight was to be divided equally between them—fixed rates, and freedom from the system of cutting which they had all found so harassing and disastrous. That is, the South Improvement Company, which was to include the entire refining capacity of the company, was to act as the evener of the oil business.[8]

It was on the second of January, 1872, that the organisation of the South Improvement Company was completed. The day before the Standard Oil Company of Cleveland increased its capital from $1,000,000 to $2,500,000, "all the stockholders of the company being present and voting therefor."[9] These stockholders were greater by five than in 1870, the names of O. B. Jennings, Benjamin Brewster, Truman P. Handy, Amasa Stone, and Stillman Witt having been added. The last three were officers and stockholders in one or more of the railroads centring in Cleveland. Three weeks after this increase of capital Mr. Rockefeller had the charter and contracts of the South Improvement Company in hand, and was ready to see what they would do in helping him carry out his idea of wholesale combination in Cleveland. There were at that time some twenty-six refineries in the town—some of them very large plants. All of them were feeling more or less the discouraging effects of the last three or four years of railroad discriminations in favour of the Standard Oil Company. To the owners of these refineries Mr. Rockefeller now went one by one, and explained the South Improvement Company. "You see," he told them, "this scheme is bound to work. It means an absolute control by us of the oil business. There is no chance for anyone outside. But we are going to give everybody a chance to come in. You are to turn over your refinery to my appraisers, and I will give you Standard Oil Company stock or cash, as you prefer, for the value we put upon it. I advise you to take the stock. It will be for your good." Certain refiners objected. They did not want to sell. They did want to keep and manage their business. Mr. Rockefeller was regretful, but firm. It was useless to resist, he told the hesitating; they would certainly be crushed if they did not accept his offer, and he pointed out in detail, and with gentleness, how beneficent the scheme really was—preventing the creek refiners from destroying Cleveland, ending competition, keeping up the price of refined oil, and eliminating speculation. Really a wonderful contrivance for the good of the oil business.

That such was Mr. Rockefeller's argument is proved by abundant testimony from different individuals who succumbed to the pressure. Mr. Rockefeller's own brother, Frank Rockefeller, gave most definite evidence on this point in 1876 when he and others were trying to interest Congress in a law regulating interstate commerce.

"We had in Cleveland at one time about thirty establishments, but the South Improvement Company was formed, and the Cleveland companies were told that if they didn't sell their property to them it would be valueless, that there was a combination of railroad and oil men, that they would buy all they could, and that all they didn't buy would be totally valueless, because they would be unable to compete with the South Improvement Company, and the result was that out of thirty there were only four or five that didn't sell."

"From whom was that information received?" asked the examiner.

"From the officers of the Standard Oil Company. They made no bones about it at all. They said: 'If you don't sell your property to us it will be valueless, because we have got advantages with the railroads.'"

"Have you heard those gentlemen say what you have stated?" Frank Rockefeller was asked.

"I have heard Rockefeller and Flagler say so," he answered.

W. H. Doane, whose evidence on the first rebates granted to the Cleveland trade we have already quoted, told the Congressional committee which a few months after Mr. Rockefeller's great coup tried to find out what had happened in Cleveland: "The refineries are all bought up by the Standard Oil works; they were forced to sell; the railroads had put up the rates and it scared them. Men came to me and told me they could not continue their business; they became frightened and disposed of their property." Mr. Doane's own business, that of a crude oil shipper, was entirely ruined, all of his customers but one having sold.

To this same committee Mr. Alexander, of Alexander, Scofield and Company, gave his reason for selling:

"There was a pressure brought to bear upon my mind, and upon almost all citizens of Cleveland engaged in the oil business, to the effect that unless we went into the South Improvement Company we were virtually killed as refiners; that if we did not sell out we should be crushed out. My partner, Mr. Hewitt, had some negotiations with parties connected with the South Improvement Company, and they gave us to understand, at least my partner so represented to me, that we should be crushed out if we did not go into that arrangement. He wanted me to see the parties myself; but I said to him that I would not have any dealings with certain parties who were in that company for any purpose, and I never did. We sold at a sacrifice, and we were obliged to. There was only one buyer in the market, and we had to sell on their terms or be crushed out, as it was represented to us. It was stated that they had a contract with railroads by which they could run us into the ground if they pleased. After learning what the arrangements were I felt as if, rather than fight such a monopoly, I would withdraw from the business, even at a sacrifice. I think we received about forty or forty-five cents on the dollar on the valuation which we placed upon our refinery. We had spent over $50,000 on our works during the past year, which was nearly all that we received. We had paid out $60,000 or $70,000 before that; we considered our works at their cash value worth seventy-five per cent. of their cost. According to our valuation our establishment was worth $150,000, and we sold it for about $65,000, which was about forty or forty-five per cent. of its value. We sold to one of the members, as I suppose, of the South Improvement Company, Mr. Rockefeller; he is a director in that company; it was sold in name to the Standard Oil Company, of Cleveland, but the arrangements were, as I understand it, that they were to put it into the South Improvement Company. I am stating what my partner told me; he did all the business; his statement was that all these works were to be merged into the South Improvement Company. I never talked with any members of the South Improvement Company myself on the subject; I declined to have anything to do with them."

Mr. Hewitt, the partner who Mr. Alexander says carried on the negotiations for the sale of the business, appeared before an investigating committee of the New York State Senate in 1879 and gave his recollections of what happened. According to his story the entire oil trade in Cleveland became paralysed when it became known that the South Improvement Company had "grappled the entire transportation of oil from the West to the seaboard." Mr. Hewitt went to see the freight agents of the various roads; he called on W. H. Vanderbilt, but from no one did he get any encouragement. Then he saw Peter H. Watson of the Lake Shore Railroad, the president of the company which was frightening the trade. "Watson was non-committal," said Mr. Hewitt. "I got no satisfaction except, 'You better sell—you better get clear—better sell out—no help for it.'" After a little time Mr. Hewitt concluded with his partners that there was indeed "no help for it," and he went to see Mr. Rockefeller, who offered him fifty cents on the dollar on the constructive account. The offer was accepted. There was nothing else to do, the firm seems to have concluded. When they came to transfer the property Mr. Rockefeller urged Mr. Hewitt to take stock in the new concern. "He told me," said Mr. Hewitt, "that it would be sufficient to take care of my family for all time, what I represented there, and asking for a reason, he made this expression, I remember: 'I have ways of making money that you know nothing of.'"

A few of the refiners contested before surrendering. Among these was Robert Hanna, an uncle of Mark Hanna, of the firm of Hanna, Baslington and Company. Mr. Hanna had been refining since July, 1869. According to his own sworn statement he had made money, fully sixty per cent. on his investment the first year, and after that thirty per cent. Some time in February, 1872, the Standard Oil Company asked an interview with him and his associates. They wanted to buy his works, they said. "But we don't want to sell," objected Mr. Hanna. "You can never make any more money, in my judgment," said Mr. Rockefeller. "You can't compete with the Standard. We have all the large refineries now. If you refuse to sell, it will end in your being crushed." Hanna and Baslington were not satisfied. They went to see Mr. Watson, president of the South Improvement Company and an officer of the Lake Shore, and General Devereux, manager of the Lake Shore road. They were told that the Standard had special rates; that it was useless to try to compete with them. General Devereux explained to the gentlemen that the privileges granted the Standard were the legitimate and necessary advantage of the larger shipper over the smaller, and that if Hanna, Baslington and Company could give the road as large quantity of oil as the Standard did, with the same regularity, hey could have the same rate. General Devereux says they recognised the propriety" of his excuse. They certainly recognised its authority. They say that they were satisfied they could no longer get rates to and from Cleveland which would enable them to live, and "reluctantly" sold out. It must have been reluctantly, for they had paid $75,000 for their works, and had made thirty per cent. a year on an average on their investment, and the Standard appraiser allowed them $45,000. Truly and really less than one-half of what they were absolutely worth, with a fair and honest competition in the lines of transportation," said Mr. Hanna, eight years later, in an affidavit.[10]

Under the combined threat and persuasion of the Standard, armed with the South Improvement Company scheme, almost the entire independent oil interest of Cleveland collapsed in three months' time. Of the twenty-six refineries, at least twenty-one sold out. From a capacity of probably not over ⟨1⟩,500 barrels of crude a day, the Standard Oil Company rose in three months' time to one of 10,000 barrels. By this manoeuvre it became master of over one-fifth of the refining capacity of the United States.[11] Its next individual competitor was Sone and Fleming, of New York, whose capacity was 1,700 barrels. The Standard had a greater capacity than the entire Oil Creek Regions, greater than the combined New York refiners. The transaction by which it acquired this power was so stealthy that not even the best informed newspaper men of Cleveland knew what went on. It had all been accomplished in accordance with one of Mr. Rockefeller's chief business principles—"Silence is golden."

While Mr. Rockefeller was working out the "good of the oil business" in Cleveland, his associates were busy at other points. Charles Lockhart in Pittsburg and W. G. Warden in Philadelphia were particularly active, though neither of them accomplished any such sweeping benefaction as Mr. Rockefeller had. It was now evident what the stockholders of the South Improvement Company meant when they assured the railroads that all the refiners were to go into the scheme, that, as Mr. Warden said, they "never had any other purpose in the matter!" A little more time and the great scheme would be an accomplished fact. And then there fell in its path two of those never-to-be-foreseen human elements which so often block great maneuvres. The first was born of a man's anger. The man had learned of the scheme. He wanted to go into it, but the directors were suspicious of him. He had been concerned in speculative enterprises and in dealings with the Erie road which had injured these directors in other ways. They didn't want him to have any of the advantages of their great enterprise. When convinced that he could not share in the deal, he took his revenge by telling people in the Oil Regions what was going on. At first the Oil Regions refused to believe, but in a few days another slip born of human weakness came in to prove the rumour true. The schedule of rates agreed upon by the South Improvement Company and the railroads had been sent to the freight agent of the Lake Shore Railroad, but no order had been given to put them in force. The freight agent had a son on his death-bed. Distracted by his sorrow, he left his office in charge of subordinates, but neglected to tell them that the new schedules on his desk were a secret compact, whose effectiveness depended upon their being held until all was complete. On February 26, the subordinates, ignorant of the nature of the rates, put them into effect. The independent oil men heard with amazement that freight rates had been put up nearly 100 per cent. They needed no other proof of the truth of the rumours of conspiracy which were circulating. It now remained to be seen whether the Oil Regions would submit to the South Improvement Company as Cleveland had to the Standard Oil Company.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 2. First act of incorporation of the Standard Oil Company.

- ↑ Testimony of Mr. Alexander before the Committee of Commerce of the United States House of Representatives, April, 1872.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 3. Affidavit of James H. Devereux. At the time General Devereux made this affidavit, 1880, he was president of the New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio Railroad.

- ↑ Report for 1871 of the Cleveland Board of Trade.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 4. Testimony of Henry M. Flagler on the South Improvement Company.

- ↑ List of stockholders given by W. G. Warden, secretary of the South Improvement Company, to a Congressional Investigating Committee which examined Mr. Warden and Mr. Watson in March and April, 1872.

- ↑ Article Fourth: Contract between the South Improvement Company and the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, January 18, 1872.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 5. Contract between the South Improvement Company and the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Dated January 18, 1872.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 6. Standard Oil Company's application for increase of capital stock to $2,500,000 in 1872.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 7. Affidavits of George O. Baslington.

- ↑ In 1872 the refining capacity of the United States was as follows, according to Henry's "Early and Later History of Petroleum":

Barrels Oil Regions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9,231 New York. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9,790 Cleveland. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12,732 Pittsburg. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6,090 Philadelphia. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2,061 Baltimore. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1,098 Boston. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3,500 Erie. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1,168 Other Points. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .901

Total. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .46,571