The History of the Standard Oil Company/Volume 1/Chapter 8

CHAPTER EIGHT

THE COMPROMISE OF 1880

NO doubt the indictment of Mr. Rockefeller in the spring of 1879 seemed to him the work of malice and spite. By seven years of persistent effort he had worked out a well-conceived plan for controlling the oil business of the United States. Another year and he had reason to believe that the remnant of refiners who still rebelled against his intentions would either be convinced or dead and he could rule unimpeded. But here at the very threshold of empire a certain group of people—"people with a private grievance," "mossbacks naturally left in the lurch by the progress of this rapidly developing trade," his colleagues described them to the Hepburn Commission—stood in his way. "You have taken deliberate advantage of the iniquitous practices of the railroads to build up a monopoly," they told him. "We combined to overthrow those practices so far as the oil business was concerned. You not only refused to support us in this contention, you persuaded or forced the railroads to make you the only recipient of their illegal favours; more than that, you developed the unjust practices, forcing them into forms unheard of before. Not only have you secured rebates of extraordinary value on all your own shipments, you have persuaded the railroads to give you a commission on the oil that other people ship. You are guilty of plotting against the prosperity of an industry." And they indicted him with eight of his colleagues for conspiracy.

The evidence on which the oil men based this serious charge has already been analysed. At the moment they brought their suit for conspiracy what was their situation? They had several months before driven the commonwealth of Pennsylvania to bring suits against four railroads operating within its borders and against the Standard pipe-lines for infringing their duties as common carriers. Partial testimony had been taken in the case against the Pennsylvania road and in that against the United Pipe Lines. These suits, though far from finished, had given the Producers' Union the bulk of the proof on which they had secured the indictment of the Standard officials for conspiracy. Now, since the railroads and the pipe-lines were the guilty ones—that is, as it was they who had granted the illegal favours, and as they were the only ones that could surely be convicted, it seems clear that the only wise course for the producers would have been to prosecute energetically and exclusively these first suits. But evident as the necessity for such persistency was, and just after Mr. Cassatt had startled the public and given the Union material with which it certainly in time could have compelled the commonwealth to a complete investigation, the producers interrupted their work by bringing their spectacular suit for conspiracy—a suit which perhaps might have been properly instituted after the others had been completed, but which, introduced now, completely changed the situation, for it gave the witnesses from whom they were most anxious to hear a loophole for escape.

For instance, the officials of the Standard pipe-lines had been instructed to appear on the 14th of May, 1879, to answer questions which earlier in the trial they had refused to answer "on advice of counsel." Now the president of the United Pipe Lines, J. J. Vandergrift, and the general manager, Daniel O'Day, were both included in the indictment for conspiracy. The evening before the interrogatory the producers' counsel received a telegram from the attorney-general of the state, announcing that the pipe-line people were complaining that the testimony which they would be called on to give on the morrow would be used against them in the conspiracy trial—as it undoubtedly would have been—and that he thought it only fair that their hearing be postponed until after that suit. And so the defendants gained time—the chief desideratum of defendants who do not wish to fight.

Soon after, the conspiracy case was again used to excellent advantage by the Standard people in the investigation which was being conducted in New York before the Hepburn Commission. Mr. Bostwick, the Standard Oil buyer, whose order to buy immediate shipment oil only at a discount had been one of the oil men's chief grievances for a year and a half, was summoned as a witness; but Mr. Bostwick too was under indictment for conspiracy, and when the examiners began to put questions to him which the producers were eager to have answered, he asked: "How can I, a man soon to be tried for conspiracy, be expected to answer these questions? I shall incriminate myself." He was sustained in his plea, and about all the Hepburn Commission got out of him was, "I refuse to answer, lest I incriminate myself." This, then, was the first fruit of the producers' hasty and vindictive suit. It had shut the mouths of the important Standard witnesses.

Discouraging as this discovery was, however, there was no reason why the suits against the railroads should not have been pushed through, and the testimony the officials unquestionably could be made to give, now that Mr. Cassatt had set the pace, have been obtained. But the Producers' Union had lost sight for the moment of the fact that the fundamental difficulty in the trouble was the illegal discrimination of the common carriers. The Union was so much more eager to punish Mr. Rockefeller than it was to punish the railroads, that in bringing the suit for conspiracy it was even guilty of leniency toward the officials of the Pennsylvania. Certainly, if there was to be an indictment for conspiracy, all the supposed conspirators should have been included. It was by discriminations clearly contrary to the constitution of the state that the Pennsylvania Railroad had made it possible for Mr. Rockefeller to achieve his monopoly in Pennsylvania. The Union had proof of these rebates, but they let off Mr. Scott and Mr. Cassatt because "they professed the greatest desire to get rid of Standard domination, and were loudly asserting that they had been victimised and compelled at times to carry oil freights at less than cost."[1] Evidently the fate of the settlement the oil men had made seven years before with Mr. Scott and the presidents of the other oil-bearing roads had been forgotten. Naturally enough the railroads took advantage of these signs of leniency on the part of the producers, and brought all their enormous influence to bear on the state authorities to delay hearings and bring about a settlement. The Pennsylvania secured delays up to December, 1879, and then the Governor ordered the attorney-general to stop proceedings against the road until the testimony had been taken in the other four cases; that is, in the cases against (1) the United Pipe Lines; (2) the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern; (3) the Dunkirk, Allegheny and Pittsburg, and (4) the Atlantic and Great Western. It was a heavy blow to the Union, for at the moment its hands were tied by the conspiracy case, as far as the United Pipe Lines were concerned, and the three railroads were foreign corporations, only having branches in Pennsylvania, and accordingly very difficult to reach. The testimony could have been obtained, however, if the Union had been undivided in its interests. It would have been done, of course, if the state authorities had been willing to do what was their obvious duty. But the state authorities really asked nothing better than to escape further prosecution of the railroads. The administration was Republican, the Governor being Henry M. Hoyt. Mr. Hoyt had been elected in the fall of 1878 and so had inherited the suits from Governor Hartranft. He was pledged, however, to see them through, for before the election the Producers' Union had sent him the following letter:

"Titusville, October 23, 1878.

"Henry M. Hoyt:

Sir—During the past few months, the Association of Producers of Petroleum, long oppressed in their immediate business and kindred industries by the persistent disregard of law by certain great corporations exercising their powers within the state of Pennsylvania, and daily subjected to incalculable loss by a powerful and corrupt combination of these corporations and individuals, have appealed to the executive, legislative and judiciary branches of the government for relief and protection.

The questions which they raise for the consideration of the authorities and the people affect not only themselves but the whole public, not only the particular calling in which they are engaged, but nearly all kinds of business in the commonwealth and the nation.

The Legislature has not responded to the demands made that the provisions of the constitution shall be speedily enforced by appropriate legislation.

The present executive has caused proceedings to be instituted in the courts looking to relief, if it can be had by process of law, and these are still pending, while others may be begun.

In view of the grave duties which will devolve upon you, should you be chosen to the high office to which you aspire, in behalf of the Petroleum Producers' Association I ask from you a definite expression of your views upon the following subjects:

First—Will you, if elected, recommend to the Legislature the passage of laws to carry into effect the third and twelfth sections of the sixteenth, and the third, seventh and twelfth sections of the seventeenth articles of the constitution of Pennsylvania?

Second—If such laws should be passed as referred to in the preceding question, will you, as Governor, approve them, if constitutional?

Third—Will you, as Governor, recommend and approve such other remedial legislation as may be required to cure the evils set forth in a memorial to Governor Hartranft of August 15, 1878?

Fourth—In the selection of the law officer of the state, will you, if elected, secure the services of one who will prosecute with vigour all proceedings already commenced or that may be instituted, having in view the subjection of corporations to the laws of the land?

Very respectfully,

A. N. Perrin,

Chairman Committee"

Governor Hoyt's answers were eminently satisfactory:

"There were provisions in the constitution," he wrote, "intended to compel the railroads and canal companies of the state to the performance of their duties as common carriers with fairness and equality, without discrimination, to all persons doing business over their lines. This policy is just and right.

"If called to a position requiring official action, I would recommend and approve any legislation necessary and appropriate to carry into effect the sections of the constitution referred to.

" It would be my duty, if elected, to see that no citizen, or class of citizens even, were subjected to hardship or injustice in their business, by illegal acts of corporations or others, where relief lay within executive control. Any proper measures or legislation which would effectually remedy the grievances set forth in the memorial addressed to Governor Hartranft would receive my recommendation and approval.

"It would be my duty, if elected, to select only such officers as would enforce obedience to the constitution and laws, both by corporations and individuals, without fear or favour, and all such officers would be held by me to strict accountability for the full and prompt discharge of all their official duties."

Governor Hoyt had indeed begun the suits, all of the testimony in regard to the Pennsylvania having been taken in his administration. This testimony must have proved to him that the transgressions of the road had been far more flagrant than anyone dreamed of—that they had amounted simply to driving certain men out of business in order to build up the business of certain other men. His evident duty, as his letter to the producers shows clearly enough that he realised, was to push the suits against the railroads even if the oil men entirely withdrew, but instead of that it became evident in the spring that he was using every opportunity to delay. Indeed, one reason the producers gave for bringing the conspiracy suit was that it would give the state authorities a scapegoat; that they would gladly act vigorously against the Standard if they were let off from prosecuting the Pennsylvania. Governor Hoyt now availed himself fully of the vacillation of the Union toward the railroads, using it as an excuse for not prosecuting the railroad cases.

But if the producers were half-hearted toward the railroads they were whole-hearted enough toward the Standard. In spite of the fact that they had gotten in their own way, so to speak, by bringing their conspiracy suit, they felt convinced that they had material enough to win it on, and they sought the extradition of the non-residents who had been indicted.

Early in June Governor Hoyt was called upon to issue a requisition for the extradition of John D. Rockefeller, William Rockefeller, H. M. Flagler, J. A. Bostwick, Daniel O'Day, Charles Pratt and G. W. Girty. A full agreement was made before the state officials, but a decision was deferred repeatedly. Finally, worn out with waiting, Mr. Campbell, in a telegram to the Governor on July 29, threatened, if there was longer delay, to make his request for extradition through the public press. The answer from Harrisburg was that the attorney-general was sick and could not attend to the matter. Mr. Campbell wired back that he was tired of "addition, division, and silence," and he sent out the following letter:

"Fairfield, July 31, 1879.

"To His Excellency Henry M. Hoyt,

Governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.Sir—On behalf of the producers of oil, whom I represent as president of their General Council, I most respectfully ask a decision at your hands, of the requisition on the Governor of the state of New York, for the surrender of the officers of the Standard Oil Company, indicted by the Grand Jury of Clarion County, and now believed to be within the limits of the state of New York.

The case was exhaustively argued before you, more than four weeks ago, and the great oil interest which I have the honour to represent has a right to a prompt decision on this vital question. If these parties—who for their own profit and its ruin control Pennsylvania's most valuable product, and compel its greatest carrier to undertake their warfare and to do their bidding at the sacrifice of its innocent stockholders—can, under the plea of being 'aliens,' defy the law of Pennsylvania and laugh at our impotent attempts to reach them, the sooner it is known the better. It is possible that if we are denied protection within the limits of our commonwealth, we may obtain justice by appealing to the courts of a sister state, where at least the defendants will be obliged to admit that they are residents.

Your obedient servant,

B. B. Campbell,

President of Producers' Council."

The Governor remained obdurate, nor was the request ever granted. In a message sent out in January, 1881, Governor Hoyt gave a review of the case—as he was compelled to do, so great was the popular criticism of his course in not pushing the suits and in refusing the request for extradition—in which he attributed his refusal to the negotiations begun between the railroads and the Producers' Union.

"The details of these negotiations, of course, need not, and did not, reach the office of the executive department," he said. "As a part of them, however, requests were presented in the interest of the petitioners (the Producers' Union) to the Governor, not to issue the requisition, followed again by requests that they be allowed to go out. Finding that the highest process of the commonwealth was being used simply as leverage for and against the parties to these negotiations between contending litigants, and that, however entire and perfect might have been the good faith in which the criminal proceedings in Clarion County had been commenced, they were being regarded and treated as a mere make-weight in the stages of private diplomacy, I deemed it my duty, in the exercise of a sound discretion, to suspend action on the requisitions."

E. G. PATTERSON

From 1872 to 1880 the chief advocate in the Oil Region of an interstate commerce law. Assisted in drafting the bills of 1876 and 1880. Abandoned the independent interests at the time of the compromise of 1880.

ROGER SHERMAN

Chief counsel of the Petroleum Producers' Union from 1878 to 1880. From 1880 to 1885 counsel for the Standard Oil Company. From 1885 to his death in 1893 counsel of the allied independents.

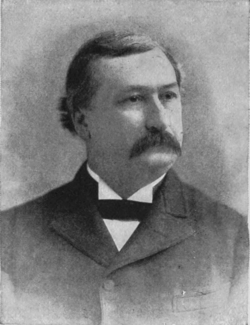

BENJ. B. CAMPBELL

President of the Petroleum Producers' Union from 1878 to 1880. Independent refiner and operator until his death.

JOSIAH LOMBARD

Prominent independent refiner of N. Y. City, whose firm was the only one to keep its contract with the Tidewater Pipe Line Company in 1880.

The writer has examined all the private correspondence which passed at this time between the litigants, but finds no proof of Governor Hoyt's statement that the Union at one time ceased its demands for Mr. Rockefeller's extradition.

The conspiracy suit had been set for the August session of the Clarion County court. When August came the Standard sought a continuance, and it was granted. The delay did not in any way discourage the producers, and when Mr. Rockefeller became convinced of this he tried conciliation. "Come, let us reason together," has always been a favourite proposition of Mr. Rockefeller. He would rather persuade than coerce, rather silence than fight. He had been making peace overtures ever since the suits began. The first had been in the fall of 1878, soon after they were instituted, when he sent the following letter to Captain Vandergrift:

"Captain J. J. Vandergrift:

My dear Sir—We are now prepared to enter into a contract to refine all the petroleum that can be sold in the markets of the world at a low price for refining. Prices of refined oil to be made by a joint committee of producers and refiners, and the profits to be determined by these; profits to be divided equitably between both parties. This joint interest to have the lowest net rates obtainable from railroads. If your judgment approves, you may consult some of the producers upon this question. This would probably require the United Pipe Lines to make contracts and act as a clearing-house for both parties.

Very respectfully yours,

J. D. Rockefeller."

Captain Vandergrift handed the letter to the executive committee of the Producers' Union. It was returned to him without a reply. The producers had tried an arrangement of this kind with Mr. Rockefeller's National Refiners' Association in the winter of 1872 and 1873, and it had failed. The refiners had thrown up their contract when they found they could get all the oil they wanted at a lower price than they had contracted to pay the Producers' Union, from men who had not gone into that organisation. The oil country was familiar, too, with the case of the H. L. Taylor Company, whose complaint against the Standard was referred to in the last chapter. Contracts of that sort were never meant to be kept, they declared. They were meant as "sops, opiates." In November, 1878, after the testimony which had been brought out by the suit against the United Pipe Lines had been pretty well aired in the New York Sun and other papers, and one or two private suits against the railroads were creating a good deal of public discussion, an effort to secure a conference between the representatives of the Union and the Standard officials was made. The Union refused to go into it officially. A meeting was held, however, in New York on November 29, at which several well-known oil men were present. It was announced to the press in advance that it was to be an important but secret meeting between the oil producers, refiners and Standard men; that its object was to settle all grievances, and to secure a withdrawal of the impending suits. As soon as the news of this proposed meeting reached the Oil Regions, the officials of the Union promptly denied their connection with it.

Although these early efforts to get a wedge into the Producers' Union and thus secure a staying of the suits had no results, the Standard was not discouraged—it never is: there is no evidence in its history that it knows what the word means. Not being able to handle the Union as a whole, the Standard began working on individuals. By March, 1879, the idea of a compromise had become particularly strong in Oil City. Indeed, one of the several reasons advanced for bringing the conspiracy suits was that such a proceeding would defeat the efforts the Oil City branch were making to bring about a settlement with Mr. Rockefeller. Accordingly, when it became apparent to Mr. Rockefeller in the fall of 1879 that the producers meant to fight through the conspiracy suit, though they might dally over the others, he notified Roger Sherman, counsel for the Union, that he wished to lay before him a proposition looking to a settlement. The president, Mr. Campbell, was in favour of receiving the proposition. "I have no idea they will present anything we can accept," he wrote Mr. Sherman. "Still it will furnish a first-rate gauge to test how badly they are scared." And the Standard was told that the Union would consider what they had to offer. "But it is a serious question—this of settlement," replied Mr. Rockefeller. "Our trial is set for October 28. We cannot get ready for that and prepare a proposition too. Why not postpone the trial?" This was done—December 15 being set. But no proposition was made to the producers for over six weeks—then they were asked to meet the Standard men on November 29 in New York City. Piqued at the delay, the producers informed the Standard that they could no longer consider their proposition and that the trial would be pushed.

But again the Standard secured delay—this time by petitioning that the case be argued before the Supreme Court of the state. They declared that such was the state of public feeling in Clarion County that they could not obtain justice there. They charged the judges with bias and prejudice, declared secret societies were working against them, and called attention to the civil suits which were still hanging fire. Over this petition serious trouble arose in court—there was a wrangle between the judge and the Standard's counsel. The newspapers took it up—the whole state divided itself into camps, and the case was again postponed, this time until the first of the year. Postponement obtained, compromise was again proposed upon the basis of abandonment of all those methods of doing business which the producers claimed injured them, and as a mark of their sincerity the United Pipe Lines on December 24, 1879, issued an order announcing the abandonment of immediate shipment throughout the region. A meeting between the legal advisers of the two parties to discuss the proposed terms was arranged for January 7, 1880, at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City—the very time to which the trial of the case for conspiracy had been postponed. It was hardly to be expected that when such negotiations were going on in New York the trial in Clarion County would be pushed very briskly. It was not. There was a hitch again, and for the fourth time proceedings were stayed. The conferences, however, went on.

These negotiations with the Standard continued for a month, and then, early in February, Mr. Campbell, the president of the Union, called a meeting of the Grand Council for February 19, 1880, in Titusville, Pennsylvania. For several weeks the Oil Regions had known that President Campbell and Roger Sherman, the leading lawyer of the Union, were in conference with the Standard officials. It was rumoured that they were arranging a compromise, and it was suspected that the meeting now called was to consider the terms. Naturally the proposition to be made was looked for with suspicion and curiosity. The meeting was the largest the Grand Council had held for many months. It was supposed to be secret, like all gatherings of the Union, but before the first session was over, the word spread over the Oil Regions that Mr. Campbell had brought to the meeting contracts with both Mr. Rockefeller and Mr. Scott, and that they were receiving harsh criticism from the Grand Council. The very meagre accounts which exist of this gathering, historic in oil annals, show that it was one of the most exciting which was ever held in the country, and one can well believe this when one considers the bitter pill the council was asked to swallow that day. Mr. Campbell began the session by reporting that all the suits at which they had been labouring for nearly two years had been withdrawn, and that in return for their withdrawal the Standard and the Pennsylvania Railroad officials had signed con-tracts to cease certain of the practices of which the producers complained.

The Standard contract, which Mr. Campbell then presented, pledged Mr. Rockefeller, and some sixteen associates, whose names were attached to the document, to the following policy:

1. They would hereafter make no opposition to an entire abrogation of the system of rebates, drawbacks and secret rates of freight in the transportation of petroleum on the railroads.

2. They withdrew their opposition to secrecy in rate making—that is, they promised that they would not hereafter receive any rebate or drawback that the railroad company was not at liberty to make known and to give to other shippers of petroleum.

3. They abandoned entirely the policy which they had been pursuing in the management of the United Pipe Lines—that is, they promised that there should be no discrimination whatever hereafter between their patrons; that the rates should be reasonable and not advanced except on thirty days' notice; that they would make no difference between the price of crude in different districts excepting such as might be properly based upon the difference in the quality of the oil; that they would receive, transport, store and deliver all oil tendered to them, up to a production of 65,000 barrels a day. And if the production should exceed that amount they agreed that they would not purchase any so-called "immediate shipment" oil at a discount on the price of certificate oil.

4. They promised hereafter that when certificates had been given for oil taken into the custody of the pipe-lines, the transfer of these certificates should be considered as a delivery of the oil, and the tankage of the seller would be treated as free.[2]

Mr. Rockefeller also agreed in making this contract to pay the Producers' Union $40,000 to cover the expense of their litigation. In return for this money and for the abandonment of secret rebates and of the pipe-line policy to which he had held so strenuously, what was he to receive? He was not to be tried for conspiracy. And that day, after the contract had been presented to the Grand Council, Mr. Campbell sent the following telegram:

"Titusville, February 19, 1880.

"To His Excellency Henry M. Hoyt,

Governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.Sir—As prosecutor in the case of the Commonwealth vs. J. D. Rockefeller, Number 25, April Sessions of Clarion County, I consent to the withdrawal of the requisition asked of you for extradition of J. D. Rockefeller et al., the same having been in your hands undecided since July last and a nolle prosequi having been entered by leave of Court of Clarion County in the case, and I will request William L. Hindman, the prosecuting attorney, to forward a formal withdrawal.

Your obedient servant,

B. B. Campbell."

The contract with the Pennsylvania which was signed by Mr. Scott agreed, in consideration of the withdrawal of the suit against the road, to the following policy:

1. That it would make known to all shippers all rates of freight charged upon petroleum. [This was an abolition of secret rates.]

2. If any rates of freight were allowed one shipper as against another, on demand that rate was to be made known.

3. There should be no longer any discrimination in the allotment and distribution of cars to shippers of petroleum.

4. Any rebate allowed to a large shipper was to be reasonable.[3]

There were both humiliation and bitterness in the Council when the report was read—humiliation and bitterness that after two years of such strenuous fighting all that was achieved was a contract which sacrificed what everybody knew to be the fundamental principle, the principle which up to this point the producers had always insisted must be recognised in any negotiation—that the rebate system was wrong and must not be compromised with. Hard speeches were made, and Mr. Campbell's head was bowed more than once while big tears ran down his cheeks. He had worked long and hard. Probably most of the members of the Grand Council who were present had a consciousness that no one of them had done anywhere near what Mr. Campbell had done toward prosecuting their cause, and though they might object to the compromise, they could not blame him, knowing all the difficulties which had been put in the way. So they accepted the report, thanking him for his fidelity and energy, but not failing to express their disapproval of the reservation in regard to the rebate system. They ended their meeting by a resolution bitterly condemning the courts, the state administration at Harrisburg, and corporations in general:

"We declare that by the inefficiency and weakness of the secretary of internal affairs in the year 1878; by the interposition on more than one occasion of the attorney-general in 1879, by which the taking of testimony was prevented; by the failure of the present government for many months, either to grant or deny the requisition for criminals indicted for crime, within the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, fugitives to other states; and by the interference of some of the judges of the Supreme Court, by an extraordinary and, according to the best legal judgment of the land, unlawful proceeding, by which the trial of an indictment for misdemeanour pending in a local court was delayed and prevented, the alarming and most dangerous influence of powerful corporations has been demonstrated. While we accept the inevitable result forced upon us by these influences, we aver that the contest is not over and our objects not attained, but we all continue to advocate and maintain the subordination of all corporations to the laws, the constitution, and the will of the people, however and whenever expressed; that the system of freight discrimination by common carriers is absolutely wrong in principle, and tends to the fostering of dangerous monopolies; and that it is the duty of the government, by legislation and executive action, to protect the people from their growing and dangerous power."

And with this resolution the second Petroleum Producers' Union formed to fight Mr. Rockefeller came to an end.

By the morning of February 20 the Oil Regions knew of the compromise. The news was received in sullen anger. It was due to the cowardice of the state officials, the corrupting influence of corporations, the oil men said. They blamed everybody but themselves, and yet if they had done their duty the suits would never have been compromised. The simple fact is that the mass of oil men had not stood by their leaders in the hard fight they had been making. These leaders, Mr. Campbell the president, Mr. Sherman the chief counsel, and Mr. Patterson the head of the legislative committee, had given almost their entire time for two years to the work of the Union. The offices of Mr. Campbell and Mr. Patterson were both honorary, and they had both often used their private funds in prosecuting their work. Mr. Sherman gave his services for months at a time without pay. No one outside of the Council of the Union knew the stress that came upon these three men. Up to the decision to institute the conspiracy suit they had worked in harmony. But when that was decided upon Mr. Patterson withdrew. He saw how fatal such a move must be, how completely it interfered with the real work of the Union, forcing common carriers to do their duty. He saw that the substantial steps gained were given up and that the work would all have to be done over again if their suit went on. Mr. Campbell believed in it, however, and Mr. Sherman, whether he believed in it or not, saw no way but to follow his chief. The nine months of disappointment and disillusion which followed were terrible for both men. They soon saw that the forces against them were too strong, that they would never in all probability be able to get the conspiracy suit tried, and that so long as it was on the docket the proper witnesses could not be secured for the suits against the railroads. Finally it came to be a question with them what out of the wreck of their plans and hopes could they save? And they saved what the compromise granted. If the oil producers they represented, a body of some 2,000 men, had stood behind them throughout 1879 as they did in 1878 the results would have been different. Their power, their means, were derived from this body, and this body for many months had been giving them feeble support. Scattered as they were over a great stretch of country, interested in nothing but their own oil farms, the producers could only be brought into an alliance by hope of overturning disastrous business conditions. They all felt that the monopoly the Standard had achieved was a menace to their interests, and they went willingly into the Union at the start, and supported it generously, but they were an impatient people, demanding quick results, and when they saw that the relief the Union promised could only come through lawsuits and legislation which it would take perhaps years to finish, they lost interest and refused money. At the first meeting of the Grand Council of the Union in November, 1878, there were nearly 200 delegates present—at the last one in February, 1880, scarcely forty. Many of the local lodges were entirely dead. Not even the revival in the summer of 1879 of the hated immediate shipment order, which had caused so much excitement the year before, but which had not been enforced long because of the uprising, brought them back to the Union. In July the order had been put in operation again in a fashion most offensive to the oil men, it being announced by the United Pipe Lines that thereafter oil would be bought by a system of sealed bids. Blanks were to be furnished the producers, the formula of which ran:

Bradford, Pennsylvania, . . . . . . . . 187 . .

I hereby offer to sell J. A. Bostwick . . . . barrels crude oil, of forty-two gallons per barrel, at . . . . cents, at the wells, for shipment from the United Pipe Lines, within the next five (5) days, provided that any portion of the oil not delivered to you within the specified time shall be considered cancelled.

There was a frightful uproar in consequence. The morning after this announcement several hundred men gathered in front of the United Pipe Line's office in Bradford, and held an open-air meeting. They had a band on the ground which played "Hold the Fort"; and the following resolutions were adopted:

"Resolved, That the oil producers of the Northern District in meeting assembled do maintain and declare that the present shipment order is infamous in principle and disreputable in practice, and we hereby declare that we will not sell one barrel of oil in conformity with the requirements of the said order. And we pledge our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honour to resort to every legal means, to use every influence in our power to prevent any sales under the said order. And we also declare that the United Pipe Lines shall hereafter perform their duty as common carriers under the law."

That night a battalion of some 300 masked men in robes of white marched through the streets of Bradford, groaning those that they suspected of being in sympathy with the Standard methods, and cheering their friends. Again there appeared there, that night, all over the upper oil country, cabalistic signs, which had been seen there often the year before. The feeling was so intense, and the danger of riot so great, that twenty-four hours after the order for sealed bids was given, it was withdrawn. The outbreak aroused Mr. Campbell's hope that it might be possible at this moment to arouse the lodges, and he wrote a prominent oil man of Bradford asking his opinion. In reply he received the following letter. It shows very well what the leaders had to contend against. It shows, too, the point of view of a very frank and intelligent oil producer:

"Bradford, Pennsylvania, July 30, 1870.

"B. B. Campbell,

Parnassus, Pennsylvania.Dear Sir—Your despatch of yesterday from O. C. has only just reached me. As I cannot say what I want to over the wires I reply by mail.

You ask if the high-sounding wording of the declaration of rights of the producers made at their mass-meeting, held here on Monday, in which they pledged their lives, fortunes and sacred honours, means liberal subscriptions to the Council funds. I reply with sorrow and humiliation—I fear not. All this high-flown talk is buncombe of the worst kind. The producers are willing to meet in a mass-meeting held out of doors where it costs nothing even for rent of a hall, and pass any kind of a resolution that is offered. It costs nothing to do this, but when asked to contribute a dollar to the legal prosecution of these plunderers, robbers, and fugitives from justice, whom they are denouncing in their resolution, they either positively refuse, say that the Council is doing nothing, that the suits are interminable and will never end, that there is no justice to be obtained in the courts of Pennsylvania, etc., etc., or else plead poverty and say they have contributed all that they are able to.

True, the producers are poor and the suits and legal proceedings are slow, and there is much to discourage them, but I tell you, my honoured chief, that the true inwardness of this state of affairs is, that the people of the Oil Regions have by slow degrees and easy stages been brought into a condition of bondage and serfdom by the monopoly, until now, when they have been aroused to a realisation of their condition, they have not the courage and manhood left to enable them to strike a blow for liberty. And these are the people for whom you and your few faithful followers in the Council are labouring, spending (I fear wasting) your substance—neglecting your own interest to advance theirs, and all for what good—"cui bono"?

I fear you will say that I am discouraged. No, not discouraged, but disgusted with the poor, spiritless, and faint-hearted people whom you are labouring so hard to liberate from bondage. As to the prospects of raising funds for the prosecution of the suits by subscription or assessments on the Unions, I am sorry to say that I fear it is impossible—at least it is impossible for me to make any collections—and right here let me make a suggestion. I often feel that the fault may not be with the people, but with the writer. I would therefore suggest that you select from among the members of the Council any good man whom you think has the power of convincing these people that their only hope of relief lies in sustaining you in the prosecution of the suits, and therefore they must contribute to the fund. If you will do this, I will promise you that he will be hospitably received and favourably introduced by the writer. But as for depending on the unaided efforts of myself to raise funds, I fear it would be useless.

I do not write this, my friend, with a view of throwing any discouragement in your path, which, God knows, is rugged and thorny enough, but I must give vent to my righteous indignation in some way, and ask you are the producers as a class (nothing but a dd cowardly, disorganised mob as they are) worth the efforts you are putting forth to save them ?

As for myself, a single individual (and I can speak for no others), I am determined to stand with you until the end, with my best strength and my last dollar."

Now, what was this loose and easily discouraged organisation opposing? A compact body of a few able, cold-blooded men—men to whom anything was right that they could get, men knowing exactly what they wanted, men who loved the game they played because of the reward at the goal, and, above all, men who knew how to hold their tongues and wait. "To Mr. Rockefeller," they say in the Oil Regions, "a day is as a year and a year as a day. He can wait, but he never gives up." Mr. Rockefeller knew the producers, knew how feeble their staying qualities in anything but the putting down of oil wells, and he may have said confidently, at the beginning of their suits against him, as it was reported he did say, that they would never be finished. They had not been finished from any lack of material. If the suits had been pushed but one result was possible, and that was the conviction of both the Standard and the railroads; they had been left unfinished because of the impatience and instability of the prosecuting body and the compactness, resolution and watchfulness of the defendants.

The withdrawal of the suits was a great victory for Mr. Rockefeller. There was no longer any doubt of his power in defensive operations. Having won a victory, he quickly went to work to make it secure. The Union had surrendered, but the men who had made the Union remained; the evidence against him was piled up in indestructible records. In time the same elements which had united to form the serious opposition just overthrown might come together, and if they should it was possible that they would not a second time make the mistake of vacillation. The press of the Oil Regions was largely independent. It had lost, to be sure, the audacity, the wit, the irrepressible spirit of eight years before when it fought the South Improvement Company. Its discretion had outstripped its courage, but there were still signs of intelli-gent independence in the newspapers. Mr. Rockefeller now entered on a campaign of reconciliation which aimed to placate, or silence, every opposing force.

Many of the great human tragedies of the Oil Regions lie in the individual compromises which followed the public settlement of 1880; for then it was that man after man, from hopelessness, from disgust, from ambition, from love of money, gave up the fight for principle which he had waged for seven years. "The Union has surrendered," they said; "why fight on?" This man took a position with the Standard and became henceforth active in its business; that man took a salary and dropped out of sight; this one went his independent way, but with closed lips; that one shook the dust of the Oil Regions from his feet and went out to seek "God's country," asking only that he should never again hear the word "oil." The newspapers bowed to the victor. A sudden hush came over the region, the hush of defeat, of cowardice, of hopelessness. Only the "poor producer" grumbled. "You can't satisfy the producer," Mr. Rockefeller often has had occasion to remark benignantly and pitifully. The producer alone was not "convinced." He still rehearsed the series of dramatic attacks and sieges which had wiped out independent effort. He taught his children that the cause had been sold, and he stigmatised the men who had gone over to the Standard as traitors. Scores of boys and girls grew up in the Oil Regions in those days with the same feeling of terrified curiosity toward those who had "sold to the Standard" that they had toward those who had "been in jail." The Oil Regions as a whole was at heart as irreconcilable in 1880 as it had been after the South Improvement Company fight, and now it had added to its sense of outrage the humiliation of defeat. Its only immediate hope now was in the success of one of the transportation enterprises which had come into existence with the uprising of 1878 and to which it had been for two years giving what support it could. This enterprise was the seaboard pipe-line which, as we have seen, Messrs. Benson, McKelvy and Hopkins had undertaken.

- ↑ "A History of the Organisation, Purposes and Transactions of the General Council of the Petroleum Producers' Unions," 1880.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 35. Contract of Petroleum Producers' Union with Standard Combination.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 36. Agreement between B. B. Campbell and the Pennsylvania Railroad Company.