The fairy tales of Charles Perrault (Clarke, 1922)/Cinderilla; or, The Little Glass Slipper

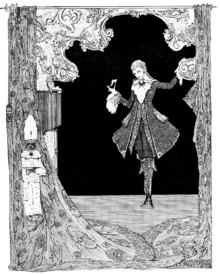

"AWAY SHE DROVE, SCARCE ABLE TO CONTAIN HERSELF FOR JOY"

(page 84)

• Cinderilla • or • The •

Little • Glass • Slipper •

ONCE there was a gentleman who married, for his second wife, the proudest and most haughty woman that was ever seen. She had, by a former husband, two daughters of her own humour and they were indeed exactly like her in all things. He had likewise, by another wife, a young daughter, but of unparalleled goodness and sweetness of temper, which she took from her mother, who was the best creature in the world.

No sooner were the ceremonies of the wedding over, but the stepmother began to shew herself in her colours. She could not bear the good qualities of this pretty girl; and the less, because they made her own daughters appear the more odious. She employed her in the meanest work of the house; she scoured the dishes, tables, &c. and rubbed Madam's chamber, and those of Misses, her daughters; she lay up in a sorry garret, upon a wretched straw-bed, while her sisters lay in fine rooms, with floors all inlaid, upon beds of the very newest fashion, and where they had looking-glasses so large, that they might see themselves at their full length, from head to foot.

The poor girl bore all patiently, and dared not tell her father, who would have rattled her off; for his wife governed him intirely. When she had done her work, she used to go into the chimney-corner, and sit down among cinders and ashes, which made her commonly be called Cinder-breech; but the youngest, who was not so rude and uncivil as the eldest, called her Cinderilla. However, Cinderilla, notwithstanding her mean apparel, was a hundred times handsomer than her sisters, tho' they were always dressed very richly.

It happened that the King's son gave a ball, and invited all persons of fashion to it. Our young misses were also invited; for they cut a very grand figure among the quality. They were mightily delighted at this invitation, and wonderfully busy in chusing out such gowns, petticoats, and head-clothes as might best become them. This was a new trouble to Cinderilla; for it was she who ironed her sisters' linen, and plaited their ruffles; they talked all day long of nothing but how they should be dressed. "For my part," said the eldest, "I will wear my red velvet suit, with French trimming." "And I," said the youngest, "shall only have my usual petticoat; but then, to make amends for that, I will put on my gold-flowered manteau, and my diamond stomacher, which is far from being the most ordinary one in the world." They sent for the best tire-woman they could get, to make up their head-dresses, and adjust their double-pinners,[1] and they had their red brushes, and patches from the fashionable maker.

Cinderilla was likewise called up to them to be consulted in all these matters, for she had excellent notions, and advised them always for the best, nay and offered her service to dress their heads, which they were very willing she should do. As she was doing this, they said to her:

"Cinderilla, would you not be glad to go to the ball?"

"Ah!" said she, "you only jeer at me; it is not for such as I am to go thither."

"Thou art in the right of it," replied they, "it would make the people laugh to see a Cinder-breech at a ball."

Any one but Cinderilla would have dressed their heads awry, but she was very good, and dressed them perfectly well. They were almost two days without eating, so much they were transported with joy; they broke above a dozen of laces in trying to be laced up close, that they might have a fine slender shape, and they were continually at their looking-glass. At last the happy day came; they went to Court, and Cinderilla followed them with her eyes as long as she could, and when she had lost sight of them she fell a-crying.

Her godmother, who saw her all in tears, asked her what was the matter.

"I wish I could—, I wish I could—;" she was not able to speak the rest, being interrupted by her tears and sobbing.

This godmother of hers, who was a Fairy, said to her:

"Thou wishest thou couldest go to the ball, is it not so?"

"Y—es," cried Cinderilla, with a great sigh.

"Well," said her godmother, "be but a good girl, and I will contrive that thou shalt go." Then she took her into her chamber, and said to her:

"Run into the garden, and bring me a pumpkin."

Cinderilla went immediately to gather the finest she could get, and brought it to her godmother, not being able to imagine how this pumpkin could make her go to the ball. Her godmother scooped out all the inside of it, leaving nothing but the rind; which done, she struck it with her wand, and the pumpkin was instantly turned into a fine coach, gilded all over with gold.

She then went to look into her mouse-trap, where she found six mice all alive, and ordered Cinderilla to lift up a little the trap-door, when giving each mouse, as it went out, a little tap with her wand, the mouse was at that moment turned into a fair horse, which altogether made a very fine set of six horses of a beautiful mouse-coloured dapple-grey.

Being at a loss for a coachman, "I will go and see," says Cinderilla, "if there be never a rat in the rat-trap, that we may make a coachman of him."

"Thou art in the right," replied her godmother; "go and look."

Cinderilla brought the trap to her, and in it there were three huge rats. The Fairy made choice of one of the three, which had the largest beard, and, having touched him with her wand, he was turned into a fat jolly coachman, who had the smartest whiskers eyes ever beheld.

After that, she said to her:

"Go again into the garden, and you will find six lizards behind the watering pot; bring them to me."

She had no sooner done so, but her godmother turned them into six footmen, who skipped up immediately behind the coach, with their liveries all bedaubed with gold and silver, and clung as close behind it, as if they had done nothing else their whole lives. The Fairy then said to Cinderilla:

"Well, you see here an equipage fit to go to the ball with; are you not pleased with it?"

"O yes," cried she, "but must I go thither as I am, in these poison nasty rags?"

Her godmother only just touched her with her wand, and, at the same instant, her clothes were turned into cloth of gold and silver, all beset with jewels. This done she gave her a pair of glass-slippers,[2] the prettiest in the whole world.

Being thus decked out, she got up into her coach; but her godmother, above all things, commanded her not to stay till after midnight, telling her, at the same time, that if she stayed at the ball one moment longer, her coach would be a pumpkin again, her horses mice, her coachman a rat, her footmen lizards, and her clothes become just as they were before.

She promised her godmother, she would not fail of leaving the ball before midnight; and then away she drove, scarce able to contain herself for joy. The King's son, who was told that a great Princess, whom no-body knew, was come, ran out to receive her; he gave her his hand as she alighted out of the coach, and led her into the hall, among all the company. There was immediately a profound silence, they left off dancing, and the violins ceased to play, so attentive was every one to contemplate the singular beauty of this unknown new comer. Nothing was then heard but a confused noise of,

"Ha! how handsome she is! Ha! how handsome she is!"

The King himself, old as he was, could not help ogling her, and telling the Queen softly, "that it was a long time since he had seen so beautiful and lovely a creature." All the ladies were busied in considering her clothes and head-dress, that they might have some made next day after the same pattern, provided they could meet with such fine materials, and as able hands to make them.

The King's son conducted her to the most honourable seat, and afterwards took her out to dance with him: she danced so very gracefully, that they all more and more admired her. A fine collation was served up, whereof the young Prince ate not a morsel, so intently was he busied in gazing on her. She went and sat down by her sisters, shewing them a thousand civilities, giving them part of the oranges and citrons which the Prince had presented her with; which very much surprised them, for they did not know her.

While Cinderilla was thus amusing her sisters, she heard the clock strike eleven and three quarters, whereupon she immediately made a curtesy to the company, and hasted away as fast as she could.

Being got home, she ran to seek out her godmother, and after having thanked her, she said, "she could not but heartily wish she might go next day to the ball, because the King's son had desired her." As she was eagerly telling her godmother whatever had passed at the ball, her two sisters knocked at the door which Cinderilla ran and opened.

"How long you have stayed," cried she, gaping, rubbing her eyes, and stretching herself as if she had been just awaked out of her sleep; she had not, however, any manner of inclination to sleep since they went from home.

"If thou hadst been at the ball," said one of her sisters, "thou wouldst not have been tired with it; there came thither the finest Princess, the most beautiful ever was seen with mortal eyes; she shewed us a thousand civilities, and gave us oranges and citrons." Cinderilla was transported with joy; she asked them the name of that Princess; but they told her they did not know it; and that the King's son was very anxious to learn it, and would give all the world to know who she was. At this Cinderilla, smiling, replied:

"She must then be very beautiful indeed; Lord! how happy have you been; could not I see her? Ah! dear Miss Charlotte, do lend me your yellow suit of cloaths which you wear every day!"

"Ay, to be sure!" cried Miss Charlotte, "lend my cloaths to such a dirty Cinder-breech as thou art; who's the fool then?"

Cinderilla, indeed, expected some such answer, and was very glad of the refusal; for she would have been sadly put to it, if her sister had lent her what she asked for jestingly.

The next day the two sisters were at the ball, and so was Cinderilla, but dressed more magnificently than before. The King's son was always by her, and never ceased his compliments and amorous speeches to her; to whom all this was so far from being tiresome, that she quite forgot what her godmother had recommended to her, so that she, at last, counted the clock striking twelve, when she took it to be no more than eleven; she then rose up, and fled as nimble as a deer.

The Prince followed, but could not overtake her. She left behind one of her glass slippers, which the Prince took up most carefully. She got home, but quite out of breath, without coach or footmen, and in her nasty old cloaths, having nothing left her of all her finery, but one of the little slippers, fellow to that she dropped. The guards at the palace gate were asked if they had not seen a Princess go out; who said, they had seen no-body go out, but a young girl, very meanly dressed, and who had more the air of a poor country wench, than a gentle-woman.

"SHE LEFT BEHIND ONE OF HER GLASS SLIPPERS, WHICH THE PRINCE TOOK UP MOST CAREFULLY"

When the two sisters returned from the ball, Cinderilla asked them if they had been well diverted, and if the fine lady had been there. They told her. Yes, but that she hurried away immediately when it struck twelve, and with so much haste, that she dropped one of her little glass slippers, the prettiest in the world, and which the King's son had taken up; that he had done nothing but look at it during all the latter part of the ball, and that most certainly he was very much in love with the beautiful person who owned the little slipper.

What they said was very true; for a few days after, the King's son caused it to be proclaimed by sound of trumpet, that he would marry her whose foot this slipper would just fit. They whom he employed began to try it on upon the Princesses, then the duchesses, and all the Court, but in vain. It was brought to the two sisters, who did all they possibly could to thrust their feet into the slipper, but they could not effect it.

Cinderilla, who saw all this, and knew her slipper, said to them laughing:

"Let me see if it will not fit me?"

Her sisters burst out a-laughing, and began to banter her. The gentleman who was sent to try the slipper, looked earnestly at Cinderilla, and finding her very handsome, said it was but just that she should try, and that he had orders to let every one make tryal. He invited Cinderilla to sit down, and putting the slipper to her foot, he found it went on very easily, and fitted her, as if it had been made of wax. The astonishment her two sisters were in was excessively great, but still abundantly greater, when Cinderilla pulled out of her pocket the other slipper, and put it on her foot. Thereupon, in came her godmother, who having touched, with her wand, Cinderilla's cloaths, made them richer and more magnificent than any of those she had before.

And now her two sisters found her to be that fine beautiful lady whom they had seen at the ball. They threw themselves at her feet, to beg pardon for all the ill treatment they had made her undergo. Cinderilla took them up, and as she embraced them, cried that she forgave them with all her heart, and desired them always to love her.

She was conducted to the young Prince, dressed as she was; he thought her more charming than ever, and, a few days after, married her.

Cinderilla, who was no less good than beautiful, gave her two sisters lodgings in the palace, and that very same day matched them with two great lords of the court.

The Moral

Beauty's to the sex a treasure,

Still admir'd beyond all measure,

And never yet was any known,

By still admiring, weary grown.

But that rare quality call'd grace,

Exceeds, by far, a handsome face;

Its lasting charms surpass the other,

And this rich gift her kind godmother

Bestow'd on Cinderilla fair,

Whom she instructed with such care.

She gave to her such graceful mien,

That she, thereby, became a queen.

For thus (may ever truth prevail)

We draw our moral from this tale.

This quality, fair ladies, know

Prevails much more (you'll find it so)

T'ingage and captivate a heart,

Than a fine head dress'd up with art.

The fairies' gift of greatest worth

Is grace of bearing, not high birth;

Without this gift we'll miss the prize;

Possession gives us wings to rise.

Another

A great advantage 'tis, no doubt, to man,

To have wit, courage, birth, good sense, and brain.

And other such-like qualities, which we

Receiv'd from heaven's kind hand, and destiny.

But none of these rich graces from above,

To your advancement in the world will prove

If godmothers and sires you disobey,

Or 'gainst their strict advice too long you stay.

- ↑ 'Pinners' were coifs with two long side-flaps pinned on. 'Double-pinners'—with two side-flaps on each side—accurately translates the French cornettes à deux rangs.

- ↑ In Perrault's tale: pantoufles de verre. There is no doubt that in the medieval versions of this ancient tale Cinderilla was given pantoufles de vair—i.e., of a grey, or grey and white, fur, the exact nature of which has been a matter of controversy, but which was probably a grey squirrel. Long before the seventeenth century the word vair had passed out of use, except as a heraldic term, and had ceased to convey any meaning to the people. Thus the pantoufles de vair of the fairy tale became, in the oral tradition, the homonymous pantoufles de verre, or glass slippers, a delightful improvement on the earlier version.