Things Seen in Holland/Chapter III

CHAPTER III

THE QUEEN AND HER PEOPLE

ALTHOUGH Queen Wilhelmina and the Dowager Queen Emma strive to encourage the wearing of the several local costumes, the custom, sad to record, has died, and is dying out in many localities. A sign of this is that ladies wear these costumes for a bal costumé, as if they were truly a thing of the past. On certain occasions the Queen affects the garb of the women of Friesland. If one wishes to see the women in their picturesque array, Zeeland, Groningen, Friesland, the southern part of Brabant, and Volendam, in North Holland, are the places to hie to on Sundays or on vegetable market-days. The women of Volendam have a weekday and a Sunday dress, but it is practically the same costume, the difference lying in the colour and striping of the outer skirt—generally one of the seven which they drag about.

dames and damsels throughout the land would require a volume. As a general rule, it may be stated, and this especially in regard to sea towns, that an abundant supply of petticoats is de rigueur, as it is considered the right thing to pretend to much embonpoint below the waist, which, in its turn, is padded out with bourrelets of wadding, or even filled with sand. A foreign lady whose embonpoint is the work of Nature is a thing of beauty and of joy to the native, who will openly express her admiration for the charms of an unartificial dikke vrouw.

The foregoing remarks naturally apply to the peasantry and fisherfolk only. With regard to The Hague, a note of smartness reveals itself in the ladies' gowns; while provincial ladies, who, when travelling outside their own country, have been bold enough to indulge in “foreign fashions,” carefully pack away these sacrifices to vanity when reaching home. The good folk in the provinces do not dress their part, but cultivate for the fashions a contempt which is pedantic and even stupid. During the recent Conference at The Hague some members of the Diplomatic Corps visited a University town, and their “Bond Street liveries” excited to derisive laughter the soberly-clad professors.

Queen Wilhelmina, in the early days of her reign affectionately referred to as Koninginnetje, or “Little Queen,” typifies in her simple life the nation over which she rules, while her tender sympathy for her people is returned by them. She rules because she is of the House of Orange, and the national cry of “Oranje boven!” always unmistakably proceeds from Dutch hearts as well as from Dutch lips. She expressed her feelings on the occasion of her “inauguration” (for of “coronation,” as we understand it, there was none), when she said at the time of taking the oath: “I count myself happy to rule the Dutch people: small in number, but great in courage—great in nature and in character.” Dapper maar klein (Brave, though small). In 1909 Queen Wilhelmina presented the nation, greatly to its joy, with an heiress to the throne, and heartfelt rejoicings took place on this occasion.

During the summer months Her Majesty lives at Het Loo (The Grove), a charming residence in Gelderland, north of Apeldoorn; in winter at the Palace in the Noordeinde, at The Hague; and for ten days in the year she occupies the Stadhuis at Amsterdam. Louis Napoleon accepted this residence as a palace, which it has remained ever since, but as William I. gave it back to the city, the Queen is the city's guest during her sojourn there.

Men and women display a predilection for jewellery, and there are in every small town—nay, in every village—one or more jewellers' shops, whose wares are as tempting as those of their fellow-shopkeepers in the cities. Gems are at a discount with the countryfolk, but ornaments in gold and silver abound. Many of these resemble the five-pointed khoumsa of the Western Arab. How did the mysterious “five” penetrate from the western coast of Morocco to the heart of the Netherlands? Did it travel from Mogador to Madrid, and thence with Alva's female camp-followers to Holland? Certain it is that rings and brooches of the khoumsa pattern are to be met with in Holland, in Belgium, and as far down the French coast as the little fishing village of Le Portel, near

A GOES MILKCART.

A Zuid Beveland milk-woman going her rounds.

Boulogne-sur-Mer, where it is known as la Portugaise. In addition to these ornaments, one greatly prized is a coral “dog-collar,” which is just as highly valued as the one of pearls worn by rich ladies in this country. Earrings there are of many shapes, from the kurkentrekkers (corkscrews)—akin to bed-springs—to the quaint ear-ornaments looking like horses' blinkers, and fitted on above the ears with projecting triangular plates studded with pearls. The most valuable of all ornaments is the gouden kap, or skull-cap of gold, of Friesland. Its price is sometimes as high as eight hundred guilders, and it is worn by the married women only, and by widows. According to a legend of Medemblik, it constitutes the glorification of the crown of thorns. A gold “back-piece” is also worn on the nape of the neck. Nor is the male sex behindhand in its love of ornament; the broad breeks are clasped at the waist with broekstukken, huge silver buttons larger than our crown-piece, some of them handed down from generation to generation. The men also affect silver chains bunched up like skeins of wool as a neck ornament. In some parts, especially in Friesland, silver shoe-buckles are still to be met with. Again, there are gold buttons in filagree to hold the gaudy necktie under control, while the wedding-ring is more or less worn by the men.

The North Holland women are reckoned very handsome—their faces are as placid as those of their ancestry; while those dwelling in the sea-towns possess eyes that are the reflex of the infinite, but are not the reflex of their thoughts. Like all fisher-folk, they have the eyes of the seer. All in all, the women have a doll-like appearance. To them is applicable the Horatian

IN ZUID BEVELAND.

Goes dairymaids in their neat and picturesque costume.

totas de capsula nitidas—to alter the gender in the quotation; they appear to have come out of a bandbox. They are very partial to eau-de-Cologne, which finds a large market in Holland, and an hotel-servant will not mind helping herself to any perfume left lying around in my lady's chamber. It is her perquisite, and she will not consider that she is doing anything wrong when liberally besprinkling her person with it. In other respects she is scrupulously honest. Another weakness of the Dutch countrywoman of the sea or country side is to compress her bosom; as a result, they are all flat-breasted to an extent that is a disfigurement of the human form, and they rival the Amazons in their flatness.

The headgear of the womenfolk varies with the locality. Every kind of cap is to be met with, from the close-fitting one of Friesland, worn by the Queen, to the Volendam cap, with its well-starched cornettes, with which opéra-bouffe has rendered us familiar in England. It is on a market-day at Middelburg or at Flushing that the visitor can more especially feast his eyes on Dutch women be-jewelled, be-capped, and be-petticoated, or again at a kermis. A shock will come to him when he sees the gouden kap surmounted by a Parisian chapeau, from either side of which peep the kurkenkrullen. The wearing of these must on such occasions be looked upon as a tribute rendered to national sentiment by these devotees of “modernism.” In the winter of 1908 Friesland revelled in a skating carnival, at which were worn the garments of days gone by, and the revival of habiliments in vogue in the days of Holland's grandeur was a welcome and picturesque one. In the museum at Hindeloopen is to be seen a fine collection of costumes of olden times.

From headgear to footwear there is, so to speak, but one step. The klomp (plural, klompen) takes rank as a national institution. These wooden shoes, or sabots, fashioned out of poplar-wood, do not merely serve to protect the feet; some of them are ornamental, notably those worn on the Island of Marken, which are daintily carved. They can be, and are, used as weapons of defence and offence. Young Dutch David will at times get on even terms with Dutch Goliath should he succeed in being the first to reach the goal aimed at with his wooden missile. Old klompen have sweet uses in their old age, for the Heintjes, Dirkjes, and Pietjes deftly convert them into tjalks (fishing-boats), and sail them along the shore, while the Arisjes, Hilletjes, and Trijntjes watch them with placid enjoyment. Many artists, more especially the veteran Josef Israëls, have immortalized the klomp when in this form. The klomp seems to be no hindrance to the movements of a broad-breeked Dutchman, for he will clear a four-foot fence like a bird without parting company with them. If anything excites the curiosity of one too short in stature to get a view of the object it is sought to look at, then will klompen placed one on top of the other be of valuable assistance. They have still another use. As the boat or ship passes through the canal the lock-keeper will appear with what seems a fishing-rod, at the end of which dangles a fish—'tis but a klomp, into which you drop the toll. I have also seen the klomp used as a most effective steering-gear on the occasion of a buxom vrouw coaxing her husband home from the tapperij, out

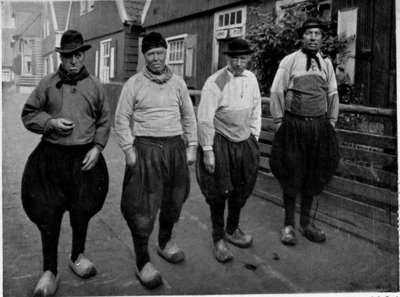

ANCIENT MARINERS.

Markeners in their characteristic “knickerbocker” garb. On their feet are klompen, or wooden shoes, which are sometimes daintily carved, and serve many purposes besides that of footgear.

of which she had hauled him. A blow on the left side of the head steered the reveller to the right, and vice versa.

There remains but to tell a pretty story in which klompen play a part. After Queen Wilhelmina had retired for the night on the day she had taken hold of the reins of Government, a notice was issued requesting the good citizens to go home quietly, and not to disturb their Sovereign's slumbers with shouts doubtlessly loyally meant. Two devotees of Bacchus who were passing by the Palace disregarded this request, to which their attention was called by some less noisy citizens, whereupon the loyalists considerately and gallantly kicked off their klompen, and zigzagged their way home in their stocking-feet.

The mode of wearing the hair calls for a passing remark. Generally speaking, it is close-cropped, and the women and girls who adopt this style—among them are to be named the Volendammers—wear under the white cap with cornettes, or “ears,” a black skull-cap which does not permit of more than a short “fringe” to be visible. Nay, more than that, it is considered indecent for a girl to allow her head to be seen bare. I can recall an instance when, in the course of a frolic between two Volendam maidens, one of them tore off the other's skull-cap; the uncovered one screamed with shame, and quickly threw her outer skirt over her head, while the older women upbraided the offender for her shameless deed, and cuffed her soundly, full-grown lass though she was. Several men were present, and in this did the indecency consist. On the other hand, the tow-headed, hard-featured, and saucy girls of the Island of Marken, but a short sail across the Zuider Zee from

“THREE LITTLE MAIDS ARE WE.”

Placid and smiling, they enjoy facing the visitor's kodak. Children in Holland have few indoor games, but the girls' chief delight seems to be in skipping and knitting.

Volendam, hold entirely different views in this respect. They parade a broad, ugly, yellow fringe of hair and a couple of long and thick krullen (curls), which give them an untidy appearance. These curls are the subject of cruel remarks on the part of the shy maidens of Volendam.

As a kermis is the occasion for a gathering of the local clan, a few words about this orgy will not be amiss. On a kermis day the Dutch throw off their placid character to such an extent that the better class fly from it, and many Hollanders do not hesitate to style the festival a national disgrace. The kermis is dying out, and it is to be hoped that a gay carnival will supplant it. The Rembrandt tercentenary showed what the Dutch can do in the matter of a pageant. Hanicotte, the French painter, whose “Leur Mer” adorns the Luxemburg, following in the steps of the old “little masters”[1]—Ostade, Jan Steen, Gerard Dou, Terborch, and others—has depicted a kermis scene, which reveals these saturnalia in all their nauseating hideousness. Many towns and villages have their kermis which lasts from three days to a week, generally the latter. During the day the inhabitants wander about the streets dancing and shouting, riding on merry-go-rounds, enjoying the attractions of more or less elevating peep-shows, and greedily gorging themselves with fried botjes (flounders), gerookten aalen (smoked eels), dried scharretje (another species of the flounder tribe), poffertjes (the American “pop-overs”), olie-bollen (balls of paste fried in oil), wafelen (waffles), and hopjes (caramels, the last the most beloved of the various kinds of lekkers). In the meanwhile, the organs of the merry-go-rounds are noisily grinding out tunes that are “popular” the world over. When night comes, Bacchus is libated in a fashion worthy of the days of Rome's decline, and men and women mingle together with a licence unknown during the rest of the year.

In Amsterdam and other big towns the kermis has been abolished. This abolition was the cause of a two days' riot in the city lying at the influx of the Amstel into the Y.

Ranking next to the kermis is the Feast of St. Nicholas, kept on December 5, the eve of the saint's name-day. His legend is widespread, as shown in our own Winchester Cathedral, and in many parts of France. The “Knickerbockers” who went to America imported the celebration of this feast into that country, where it still flourishes as Santa Claus, but where it is kept on Christmas Eve. To some of the Dutch who returned to their native land may be due Knecht Rupprecht (de zwarte knecht), the saint's man Friday, who would seem to personify the negro slave. At this festival there is a large consumption of klaasjes, special cakes taking the shape of a bishop in full canonicals.

As the children play mostly in the street, indoor games are few and far between; but outdoor games are the same, generally speaking, as played by boys in other European countries. Marbles and kooten (knuckle-bones) are universal favourites. “I am King of the Castle” (Man ik sta op je blokhuis) is a game which needs no description. The girls enjoy skipping, and when not engaged in this pastime seem to delight in knitting just as much.

Readers of H. S. C. Everard's “A History of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club, St. Andrews, from 1754 to 1900,” will have seen that there are some reasons for supposing that the game of golf may have been borrowed from the Dutch. In the Boymans Museum at Rotterdam is a picture by Jan Steen (1626-1679), “Feast of St. Nicholas: a Family Group,” wherein is the figure of a little boy who holds in one hand an undoubted golf-club and in the other a golf-ball. Other illustrations of the fact are to be met with in other pictures. It seems certain that there was played for many centuries in Holland a game known as het kolven, which closely resembled the game as we know it now. Kolfje, or little club, closely resembles the “gowfie” of Eastern Scotland. A Dutch proverb still in use says: “Dat is een kolfje naar mijn hand” (“That lies to my hand like a golf-club”), said of anything that exactly suits the speaker. Does the word “stymie,” the derivation of which still remains mysterious, come from a Dutch source? On this point Mr. Everard writes: “There is a Dutch verb stuiten, meaning to hinder or to stop. I would suggest that when an old Dutch golfer found himself ‘stymied,’ he said, Stuit mij (‘It stops me’). This phrase, with the elision of t before m (which would naturally take place in Scotland), would be contracted into ‘sty my,’ ‘stymie.’” Golf as an outdoor game is no longer much played to-day by the Dutch, although there are at least six golf-links in Holland—at Haarlem, The

Photo. Halftones Limited.

FISHERMEN'S WINTER WORK.

Volendammers ploughing the snow to make a skating track.

Hague, and Amsterdam, etc. An indoor game, reduced almost to parlour-golf, has taken its place in some localities, but even this game appears to be dying out.

It is to be regretted that the companies of doelen, who formed clubs akin to our archery clubs, but who did not belong to the army (doelen are “targeteers,” just as the Italian bersagliere derives his name from bersaglio, a target), are a thing of the past; for their prowess has been immortalized in many a painting, and their name is preserved in that of several hotels throughout the land.

Skating is, of course, the national pastime. Parties are made up to skim over the frozen rivers and canals from town to town, and much sleighing takes place in the towns after a fall of snow, the children being conveyed to school in sleighs. The Dutch excel in the exhilarating exercise of skating, and while engaged in it are, for the nonce, as light-heeled as any.

Among the students, particularly those of Leyden, rowing is greatly in vogue, and, as we know, they have sent crews to Henley. In the last year or two football for boys and hockey for girls have taken a foothold, and young Holland is going in for exercise to an extent unknown heretofore.

- ↑ In regard to the term “little masters,” Mr. David C. Preyer writes in his “The Art of the Netherlands Galleries”: “The appellation has been given through a misconception of the use of this term in Holland, where it referred originally to the size of their paintings—to their ‘little masterpieces’—and by transition to the artists who painted these. They were masters—‘great masters’— painting in ‘little.’”