Things Seen in Holland/Chapter IV

CHAPTER IV

HOLLAND'S ARTISTIC SIDE

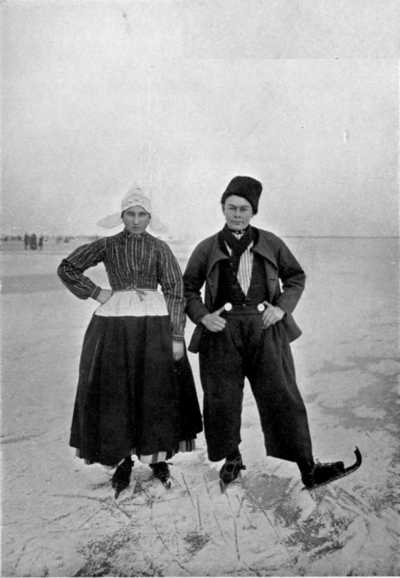

YOUNG VOLENDAMMERS SKATING.

The lad is calling attention to his valuable silver “breech-pieces.” The girl is wearing the Volendam cap with its stiffly starched cornettes.

Dutch scenery; art in the coats of arms, such as Zeeland (Sea-land), whose lion emerging from the sea, with the device Luctor et emergo (“I struggle, but I emerge”), typifies the agonies and triumphs of Zeeland.

Many a pretty story lies hidden in these symbols of organized social life. The Volendam white horse, with one of its hoofs a botje (flounder), recalls the legend of the veulen (foal or steed) which came ashore from the Zuider Zee, and was fed with wheat by a Volendam maiden, to whom for a week he daily brought a botje, in grateful recognition of her kindness, until one day the maiden was induced to bestride his back, when it carried her away for ever. Such is the Lorelei of the Zuider Zee. Edam's steer is likewise the subject of a pretty story. Once upon a time the Edammers and the Haarlemmers revelled in a sea-fight. The former were victorious, whereupon the vanquished ones paid them the following generous compliment: “We could not help being beaten by you, for you fight like steers.” “We do,” was the somewhat vainglorious rejoinder. Hence the Edam steer. It is not, as has been stated, a cow, selected because there are so many cows about the well-known cheese-town. Such an explanation verges on the ridiculous.

Art there is in the biers lying in the church at Workum, representing the various trades of the dead. The builder, the smith, the sailor, the farmer, the surgeon—each and every one was carried to his rest on the bier proper to his occupation in life. Art there is in Sneek's Water-Gate, in the Stadhuis steps of Bolsward, at Laren, the haunt of the American artist; and art there is at Volendam, where more pictures are seen in one day than can be painted in a lifetime. In the little fishing-village stands the hostelry known as “The Spaander,” from its proprietor's name. For years past it has been the rendezvous of artists of all nations. What was at first but an unpretentious yet cosy little inn has nowadays assumed greater proportions, and amid its hundreds of visitors one may number among English artists E. Burne-Jones, George Clausen, Mortimer Menpes, Stanhope Forbes, Adrian Stokes, R. Brough, Fiddes, Bartlett, Lee Hankey, Phil May, Tom Browne, Will Owen, Dudley Hardy, Cecil Alden, Walter Langley, and many others who have left on the walls of “The Spaander” souvenirs of their brush, thus converting the hostelry into a miniature gallery. America has been represented there by William Chase, Raphael Beck, John Rettig, G. Melchers, Penfield, Robinson, May A. Post, and Elizabeth Nourse. Dutch Royalty, in the person of Queen Emma, has visited this unique abode of artists. Katwijk, Scheveningen, and other sea-coast towns, are also much frequented by the brothers of the brush. The Frisian Islands deserve to be better explored by them.

To descant on the many treasures displayed in the museums or picture-galleries would carry one too far. The tourist will “do” the Rijks Museum, and content himself with a glance at Rembrandt's great painting, erroneously styled “The Night Watch,” at Paul Potter's “Bull,” in the Mauritshuis at The Hague, where is also to be seen Rembrandt's “Lesson of Anatomy,” or, again, at Franz Hals' “Jolly Toper” and “Buffoon,” likewise in the great museum of Amsterdam. But the lover of art will do more. He will pursue his studies farther, and go in quest of Hals at Haarlem, of Lucas van Leiden at Leyden, of Rembrandt's “Burgemeester Six” in the family mansion on the Heerengracht at Amsterdam, and of Jan Steen and Paul Potter at The Hague. In almost every town will he find masterpieces of the gifted painters who have depicted their country's life under every aspect and from many a point of view. For the delineations of life he will gaze upon the works of Terborch, Metsu, Netscher, Dou, Pieter de Hooch, Brouwer, and Ostade. Holland's well-known picture “The Avenue, Middelharnis,” of which our National Gallery is the fortunate and proud possessor, shows a landscape seldom to be seen in Holland nowadays. In many places, and especially in Zeeland, no trees are to be seen on the dikes, as they break them up. The story goes that the picture was exchanged by the authorities of Middelharnis for two or three paintings of little worth. Animals have been portrayed to life in the works of Karel du Jardin, Paul Potter, and several others; Willem van de Velde (father and son), Bakhuisen, Stork, and Dubbels are renowned for their marine pictures; while Van der Heist, Hals, Govert Flinck, and Bol are the painters of heroic achievements and of pictures representing doelen.

It has been said that “the first smile of the young Republic was Art, for it was only after the revolt of the Dutch against the Spanish yoke … that painting reached a high grade of perfection.” After the decline of Dutch Art in the eighteenth century, following the flourishing of the great school of the seventeenth century, Art in Holland again had its renaissance in the Hague School of the mid-nineteenth century. Israels, Jacob, Matthew, and Willem Maris, Bosboom, and Mauve were among the many great names of that movement. A newer movement has followed it, and it is at its zenith to-day. It, too, has produced a great, though perhaps a less narrowly national Art. Willem Witsen, Bloomers, Artz, Bles, Bisschop, Therese Schwartze, J. Toorop, Voerman, Verster, van Googh, Bauer, and Camerlingh Onnes all hold a high position in the annals of Dutch Art.

Holland has not produced any sculptors who are to be mentioned with the great sculptors of the Continent. Painters and sculptors require models, and these are to be found in abundance, many of the most noted ones of the day being constantly “commandeered” by foreign as well as native artists. These models have by dint of posing acquired an artistic taste, together with the critical faculty, and they are not slow in telling the artist who has not painted them to their liking that he is “not so clever as the Heer Schilder,” who has been more successful in his portrayal of them.

Among the museums there is one not so well known as the larger ones, although it has a special interest for the visitor, since it is an exact counterpart from cellar to garret of a Dutch burgher's residence in the sixteenth century. It owes its origin to Heer Willem J. Tuyn, the author of “Old Dutch Cities,” and a prominent resident of Edam, who acts as its curator. All the furniture of the period is to be found in it, all articles then in domestic use, tools, odd paintings of still more odd worthies of the time, men and women's wearing apparel, curios from the Dutch East Indies, old maps and charts, primitive

THE NIEUWE KERK AT DELFT.

It contains the monument of William of Orange.

machinery, and, all in all, so complete that a careful examination of the house's contents will give one an accurate idea of how a Dutch burgher lived in centuries gone by.

A pretty conceit, written in Old Dutch, is to be found on the fly-leaf of a Bible preserved in the museum. It runs:

Ons leven is een Schip,

d' Weerelt is de Zee,

d' Bybel 't peylcompas,

Maer 't Hemelrijk d' Ree”;

which, translated, reads:

Our life is a ship,

The world is the sea,

The Bible our compass,

But Heaven is our haven.

Delft has recently founded a Rijks-Museum, known as Huis Lambert van Meerten, the curator of which is Heer A. Le Comte, who designed the façade and made the drawings for the decoration of the interior. The building was planned by Heer J. Schouten. It is a museum of Art and applied Art. Josef Israëls, Hendrik Willem Mesdag, and the late Mevrouw Mesdag van Houten were the first contributors to the institution, which owes its origin to the late Heer van Meerten, a great and intelligent collector of things beautiful, and as early as 1894 he had entrusted to his friends Heeren Le Comte and J. Schouten the task of grouping his collection in a fine museum, but, owing to commercial losses, he was compelled to abandon his generous scheme, and his death temporarily suspended its being carried out. Thereupon a few friends formed themselves into a Dutch Art Syndicate, purchased a house, and presented the museum to the State.

The Municipality of Amsterdam has this year begun preparations to convert into a museum Rembrandt's house at No. 4, Joden-Bree-Straat, where he lived several years. It was to this house that the great painter brought his wife Saskia, and there she died; there he lived until his fortunes declined, when he sought a refuge somewhere else in the city, no one knows exactly where. This museum is to contain many valuable contributions from various public benefactors, and thus Rembrandt will be honoured in the town which has taken him to her bosom as her son; his native town of Leyden does not possess any of his works.

The churches of Holland would have been a feast for the eye had they not suffered from the iconoclasm of the Protestants, who in their zeal smashed or whitewashed all that was artistic and ornamental. When entering them one feels some sympathy with Castelar, who said: “Well, yes, I am a freethinker; but if some day I were to return to a religion, I would return to the splendid one of my fathers, and not to this squalid and nude doctrine that saddens my eyes and my heart.” At 'S Hertogenbosch (Bois-le-Duc) is one of the largest churches in Holland, and perhaps the finest architecturally; it is the only one well preserved within, as it is the centre of a Catholic province, but its inner decoration, is in poor taste. This is the Cathedral of St. John, one of the three most important medieval churches in the land, the other two being the Cathedral of Utrecht, and the Church of St. Nicholas, at Kampen. Haarlem, Leyden, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam possess Gothic churches, but all of them have suffered from the effects of bigotry. Here and there remains a carved pulpit, stained choir windows, as at Gouda, or a fine old chandelier. It may be mentioned that the choir-screen of the Cathedral of St. John is to be seen at the Victoria and Albert Museum, to which it was sold for the purpose of devoting the sum received to the inner decoration of the cathedral.

Even in the almshouses, refuges, and asylums do their residents derive benefit from the national culture of Art. Old folks, ancient mariners, and orphans are all comfortably and prettily housed, while most of the last-named wear attractive and gay costumes which do not continually remind them of their lonely condition. The Municipal Orphanage in Amsterdam contains in its regents' rooms paintings by J. Backer, Jürgen Ovens, A. de Vries, and others; while the court, with its open colonnade, is of interest. One of the sights of Amsterdam is to see a procession of girls from the Municipal Orphanage garbed in costumes in which the black and red colours of the city are displayed. Those of the Roman Catholic Orphanage wear black dresses and white caps, while those of the Walloon Orphanage wear violet-coloured gowns. A quaint and charming building, from the architectural point of view, is the Azyl voor Zeelieden (Asylum for Seafolk), to be seen at Brielle, where rest a number of old men who have sailed many a sea, and in whose features can be traced the hardy “Sea-beggars” who freed their little town from Spanish oppression. These picturesque bits are to be met with at every step of one's pilgrimage through a land whose people care with tender kindness for the aged, the poor, and the orphan.

The three historic Dutch Universities are Leyden (1575), Groningen (1624), and

DELFT'S TOWN HALL.

Restored in Renaissance style after a fire in 1618, it has an ancient Gothic belfry.

Utrecht (1636); and though Leyden had, and possibly still has, a certain precedence, they are equal in law; and with them, since 1877, has ranked the University of Amsterdam, though it is a municipal, not a State, institution. The Technical School at Delft, also, has recently been granted the status of a University. Besides the town, there is also a Free University of Amsterdam. Leyden and Utrecht have about the same number of students—700 to 800; Groningen about half that number; the Amsterdam Free about 100 to 150. The greatest number of students is found at the Delft School—some 1,100 to 1,200. None of the Universities is residential; they all follow the Scottish model (or the Scots follow them). The students lodge in the town, and are for the greater part their own masters. The course for Medicine is eight years; Law, four; Theology, five; Science, six; Philosophy and Letters, six. Each University comprises these five Faculties. The Professors hold their chairs from the Sovereign, and the body of the Professors—the Senat—is presided over by a “Rector Magnificus,” appointed (also by the Sovereign) for the scholastic year from a list of three candidates presented by the Senat—this in the State Universities. The Burgomaster is at the head of the “college” of the town University, which contains two members appointed by the Town Council and two by the Sovereign.