User:Feydey/Picturesque New Zealand

PICTURESQUE NEW ZEALAND

The Right Hon. Richard John Seddon, P.C.

PICTURESQUE

NEW ZEALAND

BY

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM

PHOTOGRAPHS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY PAUL GOODING

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published October 1913

TO MY FATHER

MILES GOODING

PREFACE

The main purpose of this book is to offer the public, and especially American readers, an intimate picture of New Zealand and its people, by one who has thrice visited its captivating shores. It is not intended as a guide-book, and mention of many places of interest more local than general is omitted in preference to the most important attractions. Nothing has been sacrificed, however, that would embarrass the author in his effort to describe the natural wonders and beauties of a country unique in geographical location, structural formation, history, and present-day conditions.

Concerning this country's sociological and industrial conditions, in themselves so large a subject, only a brief reference is made, for these matters deserve to be treated in a separate volume. The purpose of the chapters following is to afford a panoramic view, if that expression may be used, of the group of islands that constitute New Zealand, and that form far-flung outposts of the British Empire.

I take pleasure in acknowledging my indebtedness to the following sources of information:—

- New Zealand Official Year Book.

- School History of New Zealand, Frederick J. Moss.

- Hawaiki, S. Percy Smith.

- The Maori Race, E. Tregear.

- The Maoris of New Zealand, James Cowan.

- History and Traditions of the Maoris, Thomas Wayth Gudgeon.

- Maori Customs and Superstitions, John White.

- Suggestions for a History of the Origin and Migrations of the Maori People, Judge Francis Dart Fenton.

- New Zealand, James Cowan.

- Geological writings of S. Percy Smith Professor James Park, and Professor A. P. W. Thomas.

- Plants of New Zealand, Laing and Blackwell.

- Manual of the New Zealand Flora, T. F. Cheeseman.

- Forest Flora of New Zealand, T. Kirk.

- Nature Notes, Professor J. Drummond.

- New Zealand Lakes and Fiords, New Zealand Government.

- Royal Commission's Report on Kauri Gum.

- The Labor Laws of New Zealand, New Zealand Government.

- Awards, Recommendations, Agreements, etc. (under Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act), New Zealand Government.

I am also grateful to many state officials for their readiness in supplying me with information.

P. G.

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER I | ||

| A Continent in Miniature—A Near-Utopia and Corrected Misconceptions concerning it—A Busy Democracy—Political New Zealand | 1 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| Characteristics of the New Zealander—Former Cannibals who have become Good Citizens | 33 | |

| CHAPTER III | ||

| Travel in New Zealand—Government and Tourist—Slow Express—State Railways | 54 | |

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| Entering the Long Bright World—Ashore in Auckland—Reminders of America—Shops and Shopping | 62 | |

| CHAPTER V | ||

| The Thermal Wonderland—Rotorua—The Haka and the Poi—A Strange Outdoor Kitchen—Whakarewarewa's Geysers—Pantomime in a Maori Cooking Reserve—Wonderful Hamurana—Gloomy Tikitere—The Long Swim of Hinemoa—The Cold Lakes | 78 | |

| CHAPTER VI | ||

| The Buried Country—Earthquakes—The World's Greatest Geyser—A Hot Lake—The Wonders of Waiotapu | 103 | |

| CHAPTER VII | ||

| Pulsating Wairakei's Geyser Valley—The Devil's Trumpet—The Geysers and Paint-Pots of Taupo—An Immense Crater Lake—Burning Mountains—Terrifying White Island | 117 | |

| CHAPTER VIII | ||

| Weird Waitomo's Beautiful Caves—Glowworm Grotto | 132 | |

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| Down New Zealand's Rhine—Far-famed Wanganui—Amorous Taranaki | 137 | |

| CHAPTER X | ||

| New Zealand's Hilly Capital—A Win for American Literature—Hunting an Art Gallery—Welcome and Unwelcome Immigrants—A Polite Conductor—Memories of the Renowned Seddon | 149 | |

| CHAPTER XI | ||

| The Sea of the Greenstone—Two Mistakes—Christchurch—Horse-Racing and Gambling—Drunkards' Islands | 159 | |

| CHAPTER XII | ||

| Dunedin—Miscellaneous Ben Rudd and Flagstaff Hill—Roomy Invercargill—State Oysters—Romantic Stewart Island | 167 | |

| CHAPTER XIII | ||

| Lakes and Sounds of the Lone Southwest—The Rabbit Curse—Enchanting Manapouri and Te Anau—The Finest Walk in the World—Milford Sound—New Zealand's Lucerne | 178 | |

| CHAPTER XIV | ||

| Switzerland challenged—The Southern Alps—Up a Mighty Glacier—The Perverse Ski—Mountaineering by Moonlight—Within the Shadows of Mount Cook—Boiling the Billy—Over the Alps to Westland | 212 | |

| CHAPTER XV | ||

| Two Beautiful Gorges—Pelorus Jack—The Marlborough Sounds | 236 | |

| CHAPTER XVI | ||

| North Auckland—Up the Wairoa River—Historic Bay of Islands—Charming Whangaroa and its Celebrated Massacre—Kauri Gum—Life in the Back Blocks—Tarts and Kes—A Maori School and Zealous Pupils | 245 | |

| CHAPTER XVII | ||

| Wonderful Forests—The Strangling Rata and the Lordly Kauri—The Flaming Pohutukawa—Cabbage Trees—The Bowing Toitoi | 264 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | ||

| Unusual Zoology—The Gigantic Moa—Interesting Birds of To-day—A Land of Many Fishes—The Long Fish of Maui | 271 | |

| CHAPTER XIX | ||

| A Great Maori Carnival—Interviewing a Much-Married Prophet—In a Hauhau Village—A Call on King Mahuta | 279 | |

| INDEX | ||

ILLUSTRATIONS

| photographer | page | |

| The Right Hon. Richard John Seddon, P.C., thirteen years Prime Minister | Muir & Moodie | Frontispiece |

| Mount Cook from the Hooker River | Muir & Moodie | 2 |

| A Tattooed Maori | Josiah Martin | 8 |

| The Right Hon. Sir Joseph George Ward, Bart., P.C, K.C.M.G. | Muir & Moodie | 18 |

| The Hot Water Basins, White Terrace | Muir & Moodie | 22 |

| Head of Lake Wakatipu, from Pigeon Island | Muir & Moodie | 28 |

| Maori Meeting House | Muir & Moodie | 34 |

| Maori Warrior | Josiah Martin | 38 |

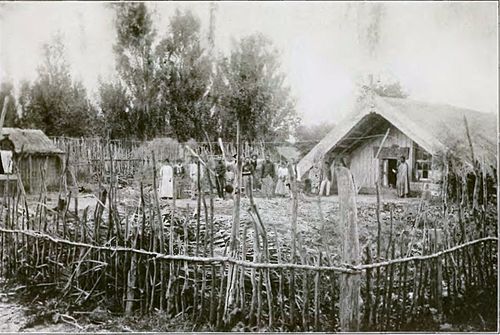

| A Maori Village | Josiah Martin | 42 |

| Maori Wahine with Mat of Kiwi Feathers and Pendent Heitiki | Iles | 50 |

| Government House, Auckland | Muir & Moodie | 56 |

| Auckland from Mount Eden | Josiah Martin | 62 |

| Queen Street, Auckland | Muir & Moodie | 66 |

| Albert Park, Auckland | Muir & Moodie | 70 |

| Maori Carvings | Muir & Moodie | 74 |

| Main Bath House, Rotorua | Muir & Moodie | 80 |

| Poi Dance | N. Z. Govt., Tourist Dept. | 84 |

| The Ducal Haka, Rotorua | Muir & Moodie | 88 |

| The Inferno Tikitere | Josiah Martin | 98 |

| Pink Terrace | Muir & Moodie | 104 |

| Waimangu Geyser | Muir & Moodie | 110 |

| Champagne Caldron | Muir & Moodie | 118 |

| Lake Taupo from Motutere | Muir & Moodie | 122 |

| Ngauruhoe in Action | Muir & Moodie | 126 |

| Aranui Cave | N. Z. Govt., Tourist Dept. | 132 |

| Wanganui River | Josiah Martin | 138 |

| London, Wanganui River | Muir & Moodie | 144 |

| Mount Egmont from Hawera | Muir & Moodie | 146 |

| Wellington Water Front | Muir & Moodie | 150 |

| Town Hall, Wellington | Muir & Moodie | 154 |

| Christchurch Cathedral | Josiah Martin | 160 |

| Christchurch from Cathedral | Muir & Moodie | 164 |

| Dunedin | Muir & Moodie | 168 |

| The Boys' High School, Dunedin | Muir & Moodie | 170 |

| Invercargill | Muir & Moodie | 174 |

| Lake Manapouri and Cathedral Peaks | Muir & Moodie | 178 |

| Safe or Happy Cove, Head of Lake Te Anau | Muir & Moodie | 182 |

| Milford Track Bush Scene | Muir & Moodie | 186 |

| Clinton Canyon from McKinnon's Pass | Muir & Moodie | 192 |

| Mitre Peak, Milford Sound | Muir & Moodie | 200 |

| The Lion, Milford Sound | Muir & Moodie | 202 |

| Queenstown and the Remarkables | Muir & Moodie | 206 |

| Section of the Alps and Tasman Glacier | Muir & Moodie | 216 |

| Cutting steps on Ice Face, Tasman Glacier | Muir & Moodie | 224 |

| Mount Sefton and the Footstool | Muir & Moodie | 232 |

| Otira Gorge, West Coast Road | Muir & Moodie | 236 |

| Buller Gorge, Hawk's Crag | Muir & Moodie | 240 |

| Wainia Falls | N. Z. Govt., Tourist Dept | 250 |

| Gum Diggers at Work in Kauri Forest | Josiah Martin | 256 |

| A Giant Kauri | Josiah Martin | 268 |

| Kiwi and Egg | Josiah Martin | 274 |

| A Tattooed Maori with Huia Feathers in Hair | Muir & Moodie | 280 |

| A Hongi | Josiah Martin | 282 |

| Women's Canoe Hurdle | Josiah Martin | 286 |

| At the Finish Line | Josiah Martin | 288 |

| Rua and Four of his Wives | J. Macquarters | 294 |

| Te Kooti's House | Josiah Martin | 310 |

| "King" Mahuta | 316 | |

| Map of New Zealand | Inside of covers |

Picturesque New Zealand

CHAPTER I

A Continent in Miniature—A Near-Utopia and corrected Misconceptions concerning it—A Busy Democracy—Political New Zealand

Far down beneath the Southern Cross, in the region of fabled Lemuria, is a long, bright land; a land of wondrous beauty and pleasing variety. There argent slopes of lofty ranges sweep down to forests of ineffable loveliness that shelter palm and fern and flowering tree. There great glaciers, littered with their rocky thefts from adjacent mountains, perpetually grind and groove, and eventually feed roaring, tawny rivers. There inroading sea and straggling lake, that fill ice-carved basins terminating far below the tides, form pictures of wild and captivating beauty.

In this land are astonishing contrasts. There the weird and the beautiful are seen side by side; fire and steam near snow and ice; spouting geyser beside cold stream; boiling, sputtering mud adjoining still, translucent depths.

Such, and much more, I found in months of travel in the Dominion of New Zealand, "The Long White Cloud," "The Far-stretching Land"; a land of the moa and the Maori. New Zealand is, indeed, a continent in miniature. No other country of the world has so great a variety of scenic charms within so small a compass. This insular unit of the British Empire is little larger than Colorado. Yet it has mountains that rival the Alps of Switzerland, and sounds that recall the fiords of Norway. It has weird fire-born wonders exceeding in extent those of the Yellowstone National Park; it has canyons with depths matching those of the Yosemite and the Grand Canyon of Arizona. In the wealth of its flora, in the poverty of its mammalia, and in its peculiar flightless avi-fauna, it is one of the most remarkable countries of the earth. In the awe-inspiring, the majestic, the enchanting, the unique, Aotearoa abounds; in diversity it is equally rich.

Not all that I had read of New Zealand did I find there. Some of the glories detailed had departed with the advance of settlement. Further, some extollers of New Zealand scenery had exaggerated; others had misplaced words of praise, applying them to hills and deforested mountains in a delirium that would have been more excusable in descriptions of the shadowy lakes and sounds and the glittering, ice-worn Alps.

But in accounts of New Zealand's physical magnificence delirious touches may be expected, especially from the New Zealander; The New Zealander who knows Niu Tirani's "Cloud Piercer" and its myriad satellites, its fiords of lake and sea, and the moss and fern-grown cliffs of its rushing canyon rivers, is proud of nature's

MOUNT COOK FROM THE HOOKER RIVER

gifts to the land of Kia ora, and in his recitals thereof there is enthusiasm. The New Zealander's pride is justifiable, it is contagious. And they from overseas who have seen these wonderful creations are prone to join him in his panegyrics. To these fortunate ones, this "Italy of the South," this "Japan of the South Pacific," is one of the most fascinating quarters of the globe.

Though this favored land is small, its total area being about 104,000 square miles, the boundaries within which its executive authority is administered are far apart. Including its island possessions, New Zealand has governmental jurisdiction within forty-two degrees of longitude and within forty-five degrees of latitude. Its northernmost possession, near the pearl-shell lagoon of Penrhyn, is only eight degrees below the Equator, while its southernmost limits, the mountainous Campbell Islands, are more than three thousand miles from Penrhyn's shoals. New Zealand itself throws its boot-like form a thousand miles along the Tasman Sea, which separates it from Australia, to the west, but its extreme breadth is only a fifth as great.

The largest land divisions of New Zealand are the North Island, about the size of Pennsylvania; the South Island, approximating the area of Florida; and Stewart Island, slightly more than half as large as Rhode Island.

New Zealand is largely mountainous. For this reason less than half its surface is suitable for agriculture. In the South Island, the more mountainous of the two main islands, nearly a fourth of the total area is valueless either for cultivation or grazing. In this island elevations of from eight to ten thousand feet are common, the highest peaks being in the Southern Alps, the island's backbone. In the North Island few of the mountains are more than four thousand feet high, and only on the loftiest of them, steaming Ruapehu, are glaciers found.

In its climatic conditions New Zealand has been likened to Italy, with which it closely corresponds in latitude. To a large extent New Zealand is a rainy land, but as the majority of its precipitations are at night and in the early morning, parts of it have sunshine records equal to some of the best obtained in Italy. In the North Island the annual rainfall is fifty-one inches, and in the South Island forty-six inches. One of the rainiest places is on the west coast of the South Island. At Hokitika, a worthy rival of Washington's Neah Bay, the annual rainfall has averaged one hundred and fifteen inches for more than a quarter of a century. Yet Hokitika is not New Zealand's rainiest place. In Dusky Sound an annual precipitation of more than two hundred inches has been recorded. Despite the assertion that New Zealand has a plentiful and regular rainfall, many parts less favored with moisture than Hokitika would like some of its rainy days, and none more so than Otago, where irrigation has been promoted to relieve the dryness of tussock plains.

Another distinguishing feature of New Zealand's climate is its windiness. Its mountains are the playground of terrific winds, and its four thousand miles of coast-line is pounded by some of the heaviest seas known to the world.

The climate of New Zealand is both varied and healthful, due to the Dominion's isolation, wide range of latitude, and the proximity of all its parts to the ocean. As for its healthful qualities, for the last twenty years the country's average annual death rate has been less than ten per one thousand inhabitants, one of the lowest death rates ever recorded anywhere.

Not for its physical charms nor its climatic characteristics, however, is New Zealand best known to the world. Its recent world fame rests mainly on its humanities to man. New Zealand has long been singled out as a striking example of the Utopian tendencies of this age. Its initiativeness, its independence and progressiveness have marked it conspicuously, and the world echoes and reechoes with its well-earned encomiums. Although New Zealand has abundant opportunity to become more democratic still, it has set an example for legislation in favor of the people that might well be imitated by earth's greatest nations.

In this stronghold of liberalism there is, in a happy degree, government of, by, and for the people. There the "interests" do not exercise a dominating influence; for "special privilege" it is practically a barren field. There the evils of private commercial monopoly are not tolerated. "Trusts" have been sighted from afar and warned off, and the growing menace of those uncovered within New Zealand has been curbed by legislation.

In New Zealand, Labor and Capital meet as "man to man." Wisely conceived labor laws provide protection for both, and, combined with rational land-tax and land-settlement legislation, have for more than twenty years assured general industrial peace and widespread prosperity. For poor and suffering humanity of all ages substantial State provision has been made. There the people are the predominating owners of public utilities; with them State ownership has become so varied and general that it has been called State socialism.

This land of model activities, now the home of multitudes from overseas, once was shunned and dreaded. In 1642, Abel Tasman, first of white men to navigate New Zealand waters, had little more than sighted it before he was attacked by Maoris, who slew three of the Zeehaan's crew, causing him to hasten back toward his Batavian base without setting a foot on shore. One hundred and twenty-seven years later, in the year of his discovery of New Zealand, Captain Cook, first of Europeans to land in New Zealand, was inhospitably received in Poverty Bay—so named by him because he could obtain no food supplies there. In an encounter between Maoris and members of his crew, one native was shot, and although the manner of his death astounded his comrades, they continued to defy the strangers.

For many years thereafter European navigators, terrified by these and other tales of deadly strife and, often, bloody feasts, feared to land on New Zealand's inhospitable coasts. It was then, in truth, a clime where men ate each other, and it was one of the most contentious places on the globe. From ghostly Te Reinga to the "Sea of the Greenstone," from treacherous Poverty Bay to the iron-sanded coasts of Taranaki, there was almost constant warfare among the natives. In later times they battled against their white invaders, and little more than forty years have passed since Maori and pakeha last clashed together in war.

New Zealand is no longer shunned. The influences of Christianity and civilization, first exerted on the Maoris by Marsden in 1814, and later by a host of other missionaries, have tamed the savage breast and forever stayed the hostile arm. The colony that the British Parliament once adjudged as too dangerous to be even the site of a convict settlement, and over which England delayed proclaiming her sovereignty until after seventy years of virtual possession, is now pointed to as a model in social achievement. To-day New Zealand is the home of more than a million white people, and every year it is the goal of thousands of immigrants.

On their arrival these immigrants find conditions remarkably different from those encountered by their predecessors of twenty-five years ago. No longer does the existence of great estates, of dog-in-the-manger land-lordism, compel them to become laborers, as that celebrated colonizer of New Zealand, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, would have had the plebeian poor among them become. They have the opportunity to become landowners, if not landlords as well, themselves. The great estates that obstructed closer settlement in early days have been acquired and subdivided by the State; those that still remain will meet a similar fate. The New Zealand immigrant of to-day can obtain land at a fair price and on easy terms, and if he wishes to borrow money to develop his acres the State will loan it to him on a long-time stipulation at a low rate of interest. If a worker, he can borrow money from the State to build himself a house, or the Government will build it for him.

New Zealand is still a young country; therefore its progress is the more remarkable. White settlement there did not really begin until about seventy years ago. Long prior thereto whalers had established stations in the colony, but they were indifferent settlers, and the districts they occupied are still among the least inhabited parts of the Dominion.

The remoteness of New Zealand was in itself no small obstacle to immigration in those days. For the twelve-thousand-mile voyage from England from three to six months were required, and the accommodations aboard ship were far inferior to those of to-day. Further, after reaching the colony there were exasperating differences and delays with the Maoris over land titles, followed by the growth of large estates near the ports of debarkation.

For years settlement proceeded slowly, though backed by lords and bishops, churches and colonizing laymen. Then the Provincial Governments began building

A TATTOOED MAORI

railways, roads increased in length, bridges became more numerous, all carrying settlement with them. Next the Central Government inaugurated a vigorous public-works policy with millions of borrowed sovereigns, and thereby brought to the colony such prosperity—and wild scrambling for public money—as it had never before known. Immediately speculation became riotous, opportunities for development in all lines increased, prices advanced, and trade improved. Increase in immigration naturally followed, the name of New Zealand became more brightly emblazoned upon the pages of history, and its fame began to spread throughout the earth. Thenceforward, until the ascendancy of the Liberal administration in 1891, prosperity and adversity, advancement and retrogression, alternated, and government succeeded government in bewildering confusion. Then came the stable administration of John Ballance and his successors, bringing with it reformatory laws and prolonged prosperity.

New Zealand's prominence has not insured it against the exaggerations of many misconceptions and careless statements. Between what the world says of New Zealand and what it actually is, there is, in many particulars, a wide difference. This variance in opinions includes the Dominion's geographical location. Many Americans do not even know where Maoriland is. Although it lies eleven hundred miles east of Australia, some persons fancy it to be within sight of the land of ungainly kangaroos; others imagine it to be near South America, from which it is separated by four thousand miles of sea; or, worse still, off the coast of Greenland. At the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburg—but let a New Zealander tell the story:—

"I had been but a short time in the United States," said this man, a resident of Wellington, "when one day I paid a visit to the Carnegie Museum. I am proud of my country, and I then believed it was about the only place on the map. Innocently thinking that the words would serve as a sort of open sesame to a hearty welcome, I said to the doorkeeper: 'I am from New Zealand.'

"'Oh,' responded he, nonchalantly, 'we get them from all parts here. Last week we had visitors from New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and other cities. But New Zealand! Let me see. What state is it in?'"

As some persons have obtained their meagre information of New Zealand from hearsay, or from newspaper interviews or articles containing half-truths or totally erroneous statements, it is but natural that they should have mistaken ideas concerning the land that Tasman viewed from ship's deck, and that Captain Cook, at a more propitious hour, seized in England's name and stocked with pigs. Such have, among other things, heard or read that New Zealand is a Socialist country; that its government is in the hands of labor; that it has no millionaires, no slums nor paupers, no industrial strikes nor lockouts, no child laborers, no trusts, no selfish, stifling land monopoly, no private employment offices. Some of these have been informed, too, that the State owns all the land, the coal mines and the forests, and all public utilities, and, finally, that the entrance standards of this blissful land "are so high," to quote one admirer of New Zealand, "that only an English-speaking person with proofs of morality and good health and a certain sum of money can enter."

In this and consecutive paragraphs I shall deal briefly with these misconceptions and contortions of facts. In some particulars these people have heard aright, in others only partially so. First, and emphatically, New Zealand is not a Socialist country. Any well-informed Socialist will tell you that, and, if he be a New Zealand Socialist, perhaps with vigor. So far is New Zealand from being a Socialist stronghold, that in the national elections of New Zealand in 1911 the Socialist candidates polled less than 5000 votes out of a total of about 470,000 votes cast at the first ballot, according to the daily press, and not more than 9000 votes according to a statement made to me by the New Zealand Socialist Party's honorary secretary. Yet New Zealand is, in a measure, a socialistic land, where, curiously, Socialists form a small minority of the people. New Zealand has socialistic legislation,—or much that has been generally so labeled,—but it has never had a Socialist administration, nor is there any imminent likelihood that it will. As yet the New Zealand Socialists have not even one member of their own number in Cabinet or Parliament.

"Why has not Socialism grown faster in New Zealand?" I asked Fred R. Cooke, the New Zealand Socialist Party's honorary secretary, in 1912.

"Because the bulk of the people," he answered, "have been persuaded that they are living under a mild form of Socialism. And then, the country has not reached the stage of capitalist evolution which forces the next stage, Socialism."

"What," I asked him, "is the New Zealand Socialist's opinion of the so-called socialistic legislation of New Zealand?"

"The New Zealand Socialist's opinion of the socialistic legislation," he replied, "is that it proves the futility of palliative legislation. The Conciliation and Arbitration Act has for many years been lauded as a piece of socialistic legislation all over the world, and the employing class, ever since it passed into law, have been pretending to fight it. Now, when the workers recognize its evils and are declaring against it, the employing class are trying to enforce conciliation and arbitration. There are many other acts which are supposed to be socialistic but they are not so."

"Is any of New Zealand's legislation truly socialistic?" I inquired of him.

"The only act passed in New Zealand which is toward Socialism is adult suffrage," he replied.

In New Zealand labor is a strong political power; yet, contrary to widespread suppositions, the Dominion has not, and never has had, a labor government. Still, labor has had much to say in, and to do with, the conduct of State affairs. Not as a separate political entity, it is true, but as the tandem mate of the Liberal party, which has been so strongly pro-labor that some have called it the Labor party. Labor will always be strong enough in New Zealand to have a voice in governmental affairs, and it is because it has had this voice for more than twenty years that it did not long ago form an enduring political party of its own and fight for supreme power, as labor did in Australia years before the formation of the New Zealand Labor parties of 1910 and 1912.

Labor has dealt capital staggering blows in New Zealand, both through land and labor laws. Yet these very laws have redounded to capital's benefit. True, they deprived it of many broad acres, through taxation and compulsory sale to the State, but this has resulted in widespread development and prosperity. They also forced capital to relinquish its dominance over labor; compelled it to abolish sweating and pay a living wage; to grant short hours and liberal overtime allowances; to provide mechanical and sanitary safeguards and conveniences for its employees; to establish a scale of compensation for accidents, with a maximum liability of $2500. At the same time, however, the exactions of labor obtained for the capitalist protection and stability; nevertheless, to many interested and disinterested observers it does seem that capitalism has been embarrassed and harassed by the multiplicity of labor acts and their amendments.

Industrially New Zealand is a comparatively peaceful land, but it is not true that it has no strikes or lockouts. However, such as it has had, since the passage of the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act and its numerous amendments, have been few, and usually of trivial consequence. Possibly the strike in New Zealand would have been more frequent if it were not, as it has been for several years, a legal offense. So, also, are lockouts. Against both employees and employers penalties for violations of the strike and lockout clauses of the Conciliation and Arbitration Act are heavy.

For nearly twenty years after the passage of this act, strikes were practically unknown in New Zealand; but recently the growing dissatisfaction of workers, particularly those allied with the New Zealand Federation of Labor,—a strong organization with principles akin to those of the Industrial Workers of the World,—has caused the strike shadow to lengthen alarmingly. The most serious strike New Zealand has had since 1890 occurred in 1912, among the gold miners of Waihi, and it lasted five months.

Perhaps nothing in this interesting land impresses the investigating visitor more than the continual disputes and adjustments between capital and labor and the numerous and frequent changes in the labor laws. What one truthfully writes of New Zealand's labor statutes this year may not be true of them next year. In this political experimental station, this social laboratory, legislative labor acts are constantly, some of them almost regularly, appearing in wholly or partially new vesture. Repeals are infrequent, amendments are many.

This legislative tinkering, as irate New Zealanders commonly call it, has been responsible for a great deal of exasperation and uncertainty in the Dominion. At every session of Parliament, for years, labor bills have been a feature of the House of Representatives' proceedings. By no means can the majority of these be truthfully construed as detrimental to commerce or industry, but harassed employers continually fear them. In innumerable instances employers have fought against specific legislation, but what they object to more than anything else, apparently, are perennial amendments, on the ground that they unsettle and otherwise injure business.

For the prevention of child labor New Zealand has passed stringent laws, and with excellent results. Nevertheless, juvenile labor of a regrettable kind still exists there. In the factory, the shop, and the mine there are no youthful workers under a reasonable age; there age limits protect them. But on dairy farms, where so often parents are poor and cows many, less satisfactory conditions prevail.

The New Zealand Government has deeply interested itself in labor, but not to such a degree as to prohibit or monopolize employment agencies. The State does conduct scores of free employment agencies, but, under the name of servants' registry offices, many employment bureaus are run by private concerns.

In New Zealand there possibly are no millionaires,—in pounds sterling,—but there are New Zealanders worth a million dollars each, and more.

Nor are there slums in New Zealand, as slums are known in great cities of the Northern Hemisphere; but in at least two of the Dominion's chief cities slums of a character that had aroused public protest existed on my last visit. Generally speaking, there is no pauperism in New Zealand, but many families have experienced pauperism for short periods, and others have been on the verge of it. In dull winters thousands of free meals have been distributed by charity organizations, and deputations of men have besought State and municipality to save them from hunger by giving them employment.

On the whole. New Zealand is a prosperous land, far more so, proportionately, than most older countries. In the same degree it is one of the richest countries of the world, both with regard to the people's material welfare and in natural resources. Likewise it is one of the most heavily indebted nations of the earth.

The per capita private wealth of the country, according to a New Zealand Government publication, is about $1800. About one tenth of the private wealth is deposited in the banks of the Dominion, and of this between thirty-five and forty per cent is held by the post-office savings banks. In them the average deposit in 1912 was about $190. If a recent estimate made by Sir Joseph Ward is approximately correct, the combined private and public wealth of New Zealand exceeds $3,250,000,000, exclusive of the incomes of wage-earners, amounting, Sir Joseph estimated, to $230,000,000 annually, and excluding the incomes from salaries and professions, totaling about $20,000,000 yearly. On a population basis of 1,060,000, this, exclusive of the incomes named, gives a combined private and public wealth of $3065 per capita.

To what does New Zealand owe its prosperity? Why is its estimated per capita wealth greater than that of the United States, considering that, little more than twenty years ago, within its borders tramping "sundowners" were met on every road, and industrial conditions were so bad that empty, neglected houses with broken windows and unkempt lawns were common?

The answer is, that New Zealand has burdened itself with an enormous national debt. Borrowed money is the prime cause of its prosperity.[1] And as one result of its borrowings there has developed a condition in which, it has been estimated, about every eighth person is dependent on the Government for a living, either as a State employee or as a dependent of such.

In 1912, the net general indebtedness of New Zealand approximated $395 per European head. In the twenty-two-year period of 1891-1913, its net national indebtedness increased one hundred and twenty per cent, or fifty-six per cent more than its increase of European population in the same time. On the whole obligation the per capita interest charges yearly total more than the per capita principal of the United States interest-bearing debt! Much of the interest outlay, however, is regained by the State in loans to settlers, workers, and local bodies. In his 1911 financial budget, Sir Joseph Ward classified about sixty per cent of the national debt as "paying interest and making profit," while about ten per cent more was declared to be "indirectly interest-bearing."

Will New Zealand be able to meet its obligations? Will it be able to repay at the specified time the 26,000,000 dollars which the 1912 official Year-Book declares is due in 1914-15; the 150,000,000 due in 1929-30; the 81,000,000 due in 1939-40? Not without renewals and fresh loans. In the Public Debt Extinction Act, however, a plan is provided whereby, with renewals to repay short-dated debentures, the existing debt can be repaid within seventy-five years. This act—passed in 1910—also provides for the repayment of all future loans within seventy-five years of their contraction. Extinction is to be accomplished by annually setting aside a certain sum for investment. Possibly this scheme will succeed, but that has been questioned, among others, by Prime Minister Massey when leader of the Opposition.

Fortunately for New Zealand, it has good assets. In 1911, Sir Joseph Ward valued its public assets at twenty per cent more than its national liabilities. Crown lands alone are worth considerably more than one hundred million dollars, and railways fully one hundred and sixty

THE RIGHT HON. SIR JOSEPH GEORGE WARD, BAR., P.C., K.C.M.G.

million dollars. As for the public works assets, however, it is difficult to reach an actual valuation, because these grow in value with increase in population and general development. Upon the latent water power which the State is to exploit, only a vague value can be put at this time. Ultimately water power, so abundant in New Zealand, should become a very valuable asset to the State.

Respecting State ownership, it is not so extensive as some persons imagine. The New Zealand Government is a great landlord, by far the greatest in the country, but not by many millions of acres does it own all the land. Its ownership is of such a magnitude, however, that, combined with constructive land laws, it has made private land monopoly impossible.

Neither does the State own all the coal mines, the forests, and public utilities. It has only three collieries, which produce less than twenty per cent of the Dominion's total coal output. The State holds immense areas of forest, but other vast sylvan domains are private freehold. It owns the railways,—excepting a few short private lines,—the telegraph lines, and, barring a few rural lines, the telephone systems; but water, gas, electric lighting and power, and street railway services are the properties of local bodies or private concerns.

Discounting exaggerated conceptions, no person, no institution in New Zealand is so busy, so versatile as that vague yet substantial entity, "The Government." Its hands are in many enterprises and benevolences, and for years it has been constantly on the lookout for new ways to occupy itself.

To-day it does business with one hand and distributes philanthropy with the other. As a direct commercial institution it operates railways, telegraph and telephone systems, coal mines, tourist steamers and motor coaches, and soon it will be selling electricity. It conducts hotels, sanatoriums, life, fire, and accident insurance offices. It is a banker, money-lender, landlord, and public trustee. As an indirect commercialist it aids dairymen by inspecting and grading their produce; it aids stockmen by keeping blooded stock for breeding; and it assists beekeepers and poultrymen by giving them free instruction.

As an altruistic institution it has established old-age and widows' pensions, superannuation funds for its employees, national endowments for pensions and education, national scholarships, and a national. State-subsidized provident fund. It has provided general protection and assistance for the laborer and assisted passages for immigrants. Industrial peace it has secured by arbitration and conciliation.

In the exercise of its purely philanthropical functions, the New Zealand Government's most noteworthy act is its gift of old-age pensions. These, which now number more than sixteen thousand, are paid to all persons who are more than sixty-five years of age and who have resided in New Zealand continuously for twenty-five years, barring allowances for absences from the country. At first the maximum annual pension was ninety dollars; now, excluding a special increase granted in 1911 to pensioners having dependent children, it is one hundred and thirty dollars, and the average pension paid is very nearly as much. To men of sixty years of age and women fifty-five years of age who have dependent on them two or more children under fourteen years of age, an annual pension of one hundred and ninety-five dollars may be paid.

In 1911, the State added to its paternal benefits pensions for widows. For widows with children and small incomes the annual pension ranges from sixty to one hundred and fifty dollars.

Another pension scheme of the State, one that is maintained partly by contributions from the beneficiaries, is the Public Service Superannuation. This provides pensions for the superannuated officials of all branches of the public service, excepting the Railway Department officials and teachers of the public schools, who have separate pension funds. The solvency of the superannuation fund is guaranteed by the State, which contributes to it a fixed sum annually.

Still another coöperative, State-guaranteed pension scheme is authorized by the National Provident Fund Act. To this fund any New Zealand resident between the ages of sixteen and forty-five, whose annual income does not exceed one thousand dollars, is entitled to contribute. One fourth of the fund is contributed by the State, Ultimately, if those whom it is intended to benefit take a proper interest in it, this fund should largely supersede old-age pensions.

After reaching the age of sixty, contributors to the fund are entitled to a weekly allowance for the rest of their lives. Other features of the scheme are the incapacity allowance, which may be drawn for a maximum period of fourteen years, and an allowance of thirty dollars for medical attendance on the birth of a contributor's child.

As for New Zealand's entrance requirements, sane mentality and morality are demanded of all its immigrants, but no white immigrant is obliged to possess any specified sum of money on landing, unless he is deemed likely to become a public charge, or is a State-assisted farmer or farm laborer. No Chinese, however, can enter New Zealand lawfully without the payment of a five-hundred-dollar head tax.

As I have said, New Zealand is a land of amazing variety, but its diversity is not confined to its physical gifts. It applies as well to its industrial and political activities. Industrially New Zealand is a beehive in which drones are relatively scarce. For those of its inhabitants who choose to work there is little excuse for idleness. Forest, farm, and factory; mine, swamp, and sea; gold and coal, flax and fish, the kauri and its gum, wool and frozen mutton, butter and cheese, a hundred manufactured articles—all these keep this land of labor busy, well fed, and well clothed.

Its export trade approximates from one hundred to

THE HOT WATER BASINS, WHITE TERRACE

one hundred and ten million dollars annually, and its imports, of which about eight per cent are received from the United States, have a total value of from eighty-five to one hundred million dollars yearly. Its wool exports yield it forty million dollars; its frozen meats, twenty millions; butter, ten millions; cheese, six millions; gold, ten millions; flax, from two to four millions; grains, provisions, and timber, twenty millions.

The greatest of all the sources of New Zealand's industrial life is the sheep. Without sheep New Zealand could not so soon have reached the commercial position it holds to-day. Its most important export is wool, which yields about one third of the total value of all exports.

In nearly all parts of the country are pastoral runs, and there are few places where I have not heard the bleating of sheep and the barking of shepherd dogs. I have startled ewe and lamb on lonely tussock plains, and have seen them feeding high on the slopes of grassy ranges. On rural roads sheep raised clouds of dust, and at many railway stations they struggled for standing room in crowded cars. In New Zealand's pastures to-day there are twenty-five million sheep,—nearly half as many as there are in the United States,—and every year between six and seven million bleat for the last time in its slaughter yards.

To shear the twenty-two thousand sheep flocks of New Zealand and handle the clip, thousands of men are employed for about six months each year. In the North Island many of the shearers are Maoris, and in the clipping sheds Maori girls are commonly employed to clean and roll the fleece. In Maoriland no industrial workers earn money faster than expert shearers. On every large station are men who shear from two hundred to two hundred and fifty sheep every day, which means a daily wage of from ten to twelve dollars.

Sheep have made many New Zealanders rich. Of the wealth of more than one dominant character in the Dominion it can be truly said, as to me it was said of Sir George Clifford, "He made it all out of wool and mutton." One sheep farmer stated in a Wellington court that he had loaned one hundred and seventy-five thousand dollars to South Americans, and that he had invested large sums in Australia and in his own country.

Politically New Zealand is a democratic Dominion, with a leaning toward imperialism. Its democracy is shown in its legislation for the masses. Its imperialistic sympathy—due to its relationship to a monarchy—is manifested by a zealous regard for, and keen efforts in the behalf of, the solidarity of the British Empire, and by heavy contributions to England's imperial navy and army,—to the first in money, to the second, as in the Boer War, in men.

Democratic as New Zealand is, it is not so democratic, in some ways, as Switzerland or certain American states. Not yet, for example, has it the initiative, the referendum, or the recall.[2] It is officially connected with a monarchy, it likes kingly honors, and it has its knighted citizens. But it cares not for all the glittering bestowals of a king. With all its love for "Home,"—in some measure due to the extensive trade relations between itself and the mother country, which buys about eighty per cent of the Dominion's exports,—New Zealand desires no hereditary titles on which to found a permanent aristocracy. It prefers a "Digger Dick" or a "Plain Bill" to a baronet.

Despite their official obligations to a kingdom, the New Zealanders govern themselves. On questions affecting Great Britain's international and intercolonial interests, imperial authorities are consulted, but otherwise New Zealand is free to legislate and govern as it chooses. In national issues both men and women have a voice. Even the Maoris enjoy universal suffrage and elect members of their own race to Parliament, and they also have their own representatives in the Legislative and Executive Councils.

At first—excepting during the year the colony was a dependency of New South Wales—the government of New Zealand was vested entirely in a Governor, who was answerable only to the Crown. In 1852, the British Parliament granted the colony a General Assembly, comprising a Legislative Council, nominated by the Governor, and an elective House of Representatives. By an act of the same year the colony was divided into six provinces, each empowered to have a presiding Superintendent and an elective Council, which was authorized to legislate on all but a few specified questions. Eventually the provinces were increased to nine, but in 1876, after bitter protests and years of widespread controversy concerning them, they were all abolished by the General Assembly.

In 1855, fifteen years after British sovereignty was proclaimed over it by Captain Hobson, its first Governor,—whose tomb is in Auckland,—New Zealand was granted a responsible system of government, under which the Executive Council became responsible to Parliament.

As New Zealand grew in wealth, fame, and prestige, it became dissatisfied with the term colony, and in 1907, at its request. King Edward VII was "graciously pleased" to advance it to the status of a Dominion. As now constituted, the government of New Zealand consists of a Governor, an Executive Council, a Legislative Council, a House of Representatives, and more than forty departments and offices.

As its official head the Dominion has a titled Governor, appointed by the King. He has many State duties but nevertheless he is little more than a graceful ornament, and as an executive official he could readily be dispensed with. The real government head is the Prime Minister.

The Governor presides over the Executive Council, an advisory aid to him, whose members he appoints, and under writs of summons from him the members of the upper house obtain and hold their seats. The Governor also has power to dissolve Parliament and to authorize the formation of another ministry. Although he possesses considerable power and authority, he seldom, it is said, exercises his initiative rights, but usually acts as advised by the Executive Council. The Governor receives annually a salary of $25,000, a household allowance of $7500, and $2500 for traveling expenses.

The Executive Council—which many New Zealanders wish to see made elective—is more forward and independent in its actions than its presiding officer. In the name of the "Government," it habitually leads the way in legislation, proposing and introducing many measures. "I propose," or "It is proposed," says the Prime Minister, in Parliament or in public interview; and Parliament, if favorably disposed, incorporates the proposals into acts which become law when approved by the Governor or assented to by the King.

The busiest officials of the New Zealand Government, apparently, are the members of this Council. They are only eight, aside from the Maori representative, yet they hold about forty portfolios. The most overworked of them,probably, is the Prime Minister. For $8000—irrespective of allowances, which are granted all ministers—he sometimes discharges the duties of as many as seven portfolios, and he never has less than five or six. The other ministers usually have from three to four portfolios each. Of these the Minister of Railways receives a salary of $6500; the other ministers get a salary of $5000 each.

The Legislative Council, the membership of which is not limited, has thirty-nine members. Prior to 1891 the members were life appointees, but since then appointments have been tenable for only seven years, though reappointments are allowed.

With its upper house New Zealand is not wholly satisfied. It admits its usefulness,—as, for instance, in protecting the people from hasty legislation. But a very large percentage of the electors are opposed to it, notwithstanding. Like Sir George Grey, sixty years ago, they want an elective Legislative Council. They maintain that the members cannot truly be representative while their nomination and tenure of office, with respect to holding over through renomination, are, they believe, dependent on the wishes of the government in power. Twenty years of continuous government, by the party responsible for the abolition of life appointments, so fully persuaded them of this that the reform of the Council was adopted by the Conservatives as a party principle in 1911, and they entered the electoral field pledged to make the upper house elective. In this effort, however, they have as yet been unsuccessful.

The House of Representatives is quite a democratic assemblage. Of its eighty members about half are industrial workers, and in 1911 seventy-five per cent of these were farmers. In that year the twenty-five agricultural

and stock farmers in the House outnumbered barristers and solicitors three to one. Altogether more than thirty occupations were represented on the membership roll, ranging from blacksmith to “gentleman.” Four members of Parliament are Maoris.

and stock farmers in the House outnumbered barristers and solicitors three to one. Altogether more than thirty occupations were represented on the membership roll, ranging from blacksmith to “gentleman.” Four members of Parliament are Maoris.

Members of the House are elected for three-year terms, and, unfair though it may seem to suffragettes, all of them are men, despite the fact that New Zealand women have had the right to vote for more than twenty years. Women voters are allowed to hold minor public offices, but for election to Parliament they cannot qualify. In one way members of the House are more fortunate than the Councillors—their individual salaries of one thousand five hundred dollars is five hundred dollars greater than the salary drawn by an “Honorable.” But the average member of the House probably earns the difference, and if he does not, he ought to have it, and needs it, to pay his campaign expenses, items which do not trouble the “M.L.C.’s.” Were it not for a legal prohibition limiting campaign expenses, some of these parliamentary seekers would have very little salary left after deducting election obligations. Fortunately for the campaigner, the law specifies that no parliamentary candidate's election liabilities shall exceed one thousand dollars.

The electoral system of New Zealand has some commendable features, but it needs still further reformation. In 1890, the Dominion established the one-man-one-vote principle; in 1893, it granted woman's suffrage; and three years later it abolished the property qualification. Now any man or woman who has been a resident of the country for one year, and of his or her district for three months immediately preceding registration, is entitled to vote. Maoris do not have to register.

No reference to the electoral system of New Zealand and the progressive laws which it has made possible would be complete without an acknowledgment of the part taken by women voters. A good percentage of the best legislation in New Zealand is in large degree attributable to the interest and energy displayed by women. The great Seddon, who obtained the franchise for women in his first year as Premier, realized this soon after the measure became law. Mr. Seddon, who pressed for the bill's passage more on account of his late superior's advocacy of its principles than because of his personal approval, also found that the women greatly strengthened his party's position at the first election in which they participated. Yet he had pictured Parliament as "plunging into an abyss of unknown depth by granting the franchise to women."

Evidently woman's suffrage has had no baneful effect on New Zealand. It was obtained without prolonged and bitter dissensions, and without the riotous, disgraceful scenes attending campaigns in its behalf in England. New Zealand's women obtained their victory quietly, and unobtrusively they have enjoyed its fruits; but though they take practically as much interest in politics as the male electors, as indicated by the number of their votes, with their present limited electoral rights they appear to be satisfied.

As a body they do not aspire to the higher political honors, and among them there is no concerted action in that direction. By male office-seekers and by Government alike, they are sought and welcomed as valued supporters of men and men's measures, but this is virtually as far as an invitation to their participation in political rewards goes. The women of New Zealand are not encouraged to seek political preferment; rather they are discouraged, directly and by palpable insinuation. Their political remunerations are exceedingly disproportionate to the value of services rendered. Even England, where the enfranchisement of women is still a burning question, gives its women a greater share in public affairs than the women of New Zealand possess.

New Zealand is a developing, a changing land. It is still, as it has been for the last quarter of a century, mainly a pastoral domain. But it is developing from an agricultural land into an industrial one, with cities and towns as its pulsating centres. Necessarily and naturally, in the wake of these transformations there must come, as there already have come, important political changes. Once the owners of great estates wielded the most powerful influence in affairs both national and local. Then, with the fairer taxation and the division of these little kingdoms, came the small freeholder, the leaseholder, and the workingman, and usurped this predominance. But, fortunate as they have been, these classes are not fully satisfied with the results obtained since the eventful days of '91. Freehold exponents, allied politically and otherwise, have been demanding a wider application of the freehold,—which the Conservatives have promised to give them,—and the working classes continue to complain of laws existing and to clamor for others yet undrawn. They have even secured union preference in a multitude of industrial agreements and Arbitration Court awards, and now they cry for the establishment of union preference by statute. In New Zealand union labor has become so strong that men have actually been fined in courts of justice for failure to join labor unions when ordered by the courts to do so, in accordance with industrial agreements or awards.

But despite it all—despite the insistent, annual demands of the laborer, "Give us more," "Give us statutory union preference," "Give us this, give us that"—despite the solemn, indignant assurances of employers that business will be ruined, and that the labor laws are killing the country—despite all this, New Zealand continues to grow, in population and trade, in public and private wealth. And it will continue to prosper, as it has for the last twenty-two years, so long as the world prospers, and so long as it is as well governed as it has been since the reforming hand of John Ballance grasped the helm of the ship of state. New Zealand has a brilliant past, but it has a still more luminous future.

CHAPTER II

Characteristics of the New Zealanders—Former Cannibals who have become Good Citizens

And now what can be said of them who have created this meritorious State? Are they, because they have accomplished so much in so brief a time, an extraordinary people; are they mentally, morally, socially superior, as individuals? In one respect, perhaps, the New Zealanders differ from the majority of mankind. As a democracy they have made more of their opportunities. They have run where others walked or wallowed. They have exhibited humanitarianism where others displayed brutality, uncharitableness, or indifference.

New Zealanders are so far from being extraordinary that they have been called parochial and conceited. On criticism laudatory of their country they smile, and, some charge, on censure frown. Many parochial and conceited New Zealanders there are, but I cannot candidly say that the average New Zealander is more parochial or conceited than are millions of people in the United States or in Europe. On subjects affecting his native heath the New Zealander undoubtedly is sensitive, but what nationalities are not so?

On the other hand, prolonged prosperity apparently has created in the New Zealander some indifference to criticism which, if heeded, might have beneficial results. It is possible that, for the development of character, New Zealand has had too much prosperity.

World-wide praise also has contributed to the New Zealander's self-complacency. With the world's eyes upon him, he sometimes proudly asks the visitor, "What do you think of our little country?" But his national pride is excusable. His land has accomplished something worthy. It has labored to alleviate the burdens of the commonalty; it has set the world a bright example.

New Zealanders are a busy, independent, and pleasure-loving people. Their popular sports are horse-racing, football, cricket, tennis, golf, swimming, and yachting. In every part of the country there is a weekly half-holiday for factories, shops, offices, the building trades, etc., and in addition there are from six to seven full holidays each year. Proof that New Zealanders enjoy themselves may be seen on any clement Saturday night, when, in the cities, thousands leisurely stroll the streets, crowding the footpaths and filling the roadways from curb to curb. Noteworthy, too, is the observance of the Sabbath. On that day scarcely a train moves; in some cities street cars do not run during church services; and all shops and hotel bars are closed. To those persons who find the customary fishing expedition or steamer excursion a tame diversion, Sunday in Aotearoa often is most pronouncedly dull.

Another noticeable characteristic of the New Zealander is his friendly feeling toward the United States. One of the stanchest supporters of friendly relations

MAORI MEETING HOUSE

with the United States is New Zealand's Chief Justice, Sir Robert Stout. "I have always been of opinion," he told me, "that we ought to have close relations with our kin beyond the sea on the Pacific. This is why I have ever advocated social and trade relations between New Zealand and the United States. And personally I have always liked the Americans I have met."

Apparently one cause of New Zealand's friendliness toward the United States is the fear of an Asiatic armed invasion. At present New Zealand appears to have little reason for such apprehension, yet, as mirrored in the press, it is held to be a possibility of the future. There are now only about three thousand Chinese in the country—much less than formerly—and in the last decade less than one hundred Japanese have entered New Zealand. It is apparent also that an imperial war with Germany has not been overlooked.

A determination to be prepared for war has caused New Zealand, partly at the suggestion of Lord Kitchener, to adopt compulsory military training. This action, though perhaps popular with the majority of New Zealand men, has been received with bitter hostility by thousands of them, and many have preferred prison sentences to enforced service. From all able-bodied males over twelve years of age military training is required until the age of twenty-five, followed by enrollment in the Reserve Force until the age of thirty.

New Zealanders are intelligent; and, answering the American woman who asked, "What language do New Zealanders speak?" they speak English. The country has one of the best public school systems in the world, and eighty-five per cent of its people can both read and write. It has primary, secondary, and high schools, technical and industrial schools, training colleges for teachers, and schools for the Maoris. It has a limited free-book system, various free scholarships, and evening continuation classes. With the exception of fees charged for instruction in the higher branches at district high schools, education in the public schools is free, and, between the ages of seven and fourteen, compulsory.

My prefatory reference to the New Zealanders would be incomplete without an accompanying introduction of the Dominion's romantic brown people. Beneath the ensign of the Southern Cross and the Union Jack dwells a race of imposing stature, almost the tallest among men. Its members, dark-haired, smiling, and robust, are intelligent, in land collectively wealthy, independent, proud, and jealous of their rights.

Such are the New Zealand Maoris, the venturesome sailors of Hawaiki, the greatest fighting people of the South Pacific. A man-eating, blood-drinking race, they yet had their poets, their orators, their astronomers and wise men. Long before Columbus braved the dangers of unknown seas the Maoris roved the wide Pacific. For thousands of miles they pushed outward from the east, west, and north in naught but canoes, discovering and populating many islands, and in New Zealand reaching their ultima Thule. The Maoris have a remarkable history, one rich in stories of the human passions, of love and hate, of merciless warfare, of cannibalism, of multitudinous superstitions and amazing, deadly suspicions. To those who love to delve into the mystic past of primitive people the history of the Maoris is a romance of romances. It carries the investigator from Arabia to America, from Northern India and Hawaii to the pathetic remnants of the Morioris in the Chatham Islands. It involves the rise and fall of nations. It tells of many migrations, of almost constant intertribal warfare. It is replete with tales of gods and demigods, of monsters of land and sea. It is bright with charming recitals of love escapades of man and maiden.

Stirring, indeed, were the days of old. For hundreds of years the militant cry of the toa rang through the land, from Hawke Bay to Taranaki, from Auckland to the greenstone isle. War was waged on a thousand pretexts: over land, women, curses, insults. Until 1869 cannibalism existed, although it had long been uncommon; and as late as 1871 Maoris warred against the colonials.

Whence came the Maoris? From Hawaiki, they say. But where is Hawaiki? There are many Hawaikis. All the myriad islands of Polynesia, from Easter Island to Ponape, from Hawaii to New Zealand, say that Hawaiki, or its equivalent in the various Polynesian dialects, was their original home; but their ideas respecting the exact location of this ancestral abode are somewhat vague. According to S. Percy Smith, at least seven Hawaikis are known, among them Hawaii, Samoa, Tahiti, and neighboring islands, and Rarotonga. Mr. Smith believes the Hawaiki of the Maoris to be Tahiti and adjoining islands. Maoris themselves say that they came from Tawhiti-nui, but it is doubtful if the first Hawaiki was situated in that part of the world.

Tentatively Mr. Smith has traced the Maoris back to India. Judge Pomander, of Hawaii, held that these Polynesians, and Polynesians in general, were a branch of the Indo-Europeans. Other investigators have traced them to Arabia, thus giving them a Caucasian origin. Professor J. Macmillan Brown has traced them to the Mediterranean's shores. By Judge Francis Dart Fenton the Maoris were accorded kinship with the Sabaians, the most celebrated of all the people of ancient Arabia. The Sabaians were "men of stature," says Jeremiah, and one of their rulers was the Queen of Sheba.

The date of the first arrival of the Maoris in New Zealand is not positively known. Judge Fenton says that apparently there were thirteen expeditions to New Zealand of which traditional accounts have been preserved, and others of which only uncertain stories exist. According to Mr. Smith, the original discovery of New Zealand by a Maori was made in the tenth century by Kupe, a high chief of Tahiti. About 1350 A.D. there reached New Zealand a fleet of six double-decked canoes. This is the greatest Maori migration known to-day.

MAORI WARRIOR

If the Hawaiki of the Maoris was Tahiti, it was a long, dreary, and dangerous voyage they were forced to make to reach New Zealand. After leaving Rarotonga, there were about two thousand statute miles of sea to navigate before reaching the northern part of Aotearoa, where nearly all the canoes landed, and there were but a few wide-scattered islands en route, at which the voyagers may or may not have halted.

When the Maoris settled in New Zealand they found it inhabited by a race generally believed, though not absolutely known, to be the Morioris, a branch of the Polynesians. Whatever race it was, it is certain that its members were soon conquered and enslaved, and many of them eaten, by the Maoris. If they were not Morioris, they have been long extinct; if they were, they have been so nearly exterminated that to-day not more than a half-dozen pure-blooded members of the race exist, and all of these live on the Chatham Islands, about five hundred miles east of Lyttleton.

Possibly the people inhabiting New Zealand prior to the Maoris were Melanesians; but the Melanesian taint seen in a few Maoris to-day is not generally regarded as evidence that a black race once lived in the Dominion. Yet one tradition says that Melanesians reached New Zealand in a canoe about 1250 A.D. Probably this relationship to the black is due to intermarriage in Fiji and westward centuries ago.

After establishing themselves in New Zealand the Maoris did not organize any intertribal governments or make any efforts to form a nation. From the first every tribe, with occasional exceptions inspired by policy, lived and fought for itself. Changes of scene, of climate, and the possession of greater chances for development, did not modify the militant propensity of these barefooted colonists. They warred as they did in Hawaiki. Over all the land blood was spilled; whole tribes were destroyed, and cannibal feasts were common. Every able man was a warrior, ready at an instant's notice to exchange the peace of home for the strife of battle-field. On fortified hills the Maori ensconced himself, and there, day and night, watched and waited for his enemies; or, with spear, sword, club, and tomahawk, sallied forth for conquest.

Apparently the Maoris were constantly at war because they loved it, but John White says they did not, "though when once in it they are so proud that they cannot think of wishing or offering terms of peace." Undoubtedly the majority of Maori wars were due to violations of the Maori's code. Possibly no people had a nicer sense of honor, "in the old acceptation of the term," says Gudgeon, than the Maori. To him the slightest insult or injury "was unbearable, and therefore quickly avenged, even when the injured tribe was weak compared with the enemy." A single tribesman could start a war merely by a verbal insult. Even a fancied insult from a child has caused war.

A feature of Maori warfare was cannibalism, the worst stage of which was reached in Hongi's wars. Long prior to this, cannibalism had gratified appetite both in war and peace. This was so generally known to early navigators to New Zealand that for years, the terror of cannibalism prevented intercourse with the natives. In 1780, when in the House of Commons New Zealand was proposed as a suitable place for a convict colony, "the cannibalistic propensities of the natives was urged in opposition and silenced every other argument."

By many Maoris human flesh was classed as the best of all flesh. Some Maoris were so eager for food of this sort that they lay in wait for victims "like the tigers of India." Many of the victims of cannibalism were slaves, some of whom were eaten in peaceful times. One writer says that occasionally even children were eaten. Yet the Maoris liked children so well that they spoiled them. When children were the offspring of an enemy, however, it was considered proper to eat them.

As the Maoris increased in numbers in New Zealand, they spread over the land until, from the North Cape to the Bluff, not an inch of soil remained unclaimed. And all land claims were guarded with the most jealous care. The Maori was always sure of his boundaries. His landmarks were trees, streams, stones, holes, posts, rattraps, and eel-dams. These boundaries were thoroughly memorized. Patiently and minutely their names, location, and characteristics were implanted in the minds of Maori youth by father and grandfather. Instruction also was given in all important history connected with the acquirement and possession of the land. And all these lessons were treasured by the pupil with a memory that, says Judge Fenton, was reliable up to twenty Maori generations, or five hundred years.

A dispute over landmarks among such positive, combative memorizers was sure to lead to serious trouble. That which the Maori regarded as his "mother's milk," and his "life from childhood," he at all times was ready to risk his life to retain. Considering the complex nature of Maori land titles, it is not surprising that there was a multitude of land disputes, or that many land title tangles try the patience of the Native Land Court to-day.

Some of the claims made by native landowners are amazing. One Maori believed he was entitled to a tract of land because he had been cursed on it. Another claimed ownership because he had been injured on the property involved. By the Colonial Government one claim actually was allowed because one of the claimants swore that he had seen a ghost on the disputed land.

The Maoris have always held land in common, and to a very large extent they so hold their five million acres to-day. To them communal ownership seems to be satisfactory, but when a white man leases a piece of their land he may not find the system so agreeable. When the first rent-day arrives he, like the Bay of Plenty physician I heard about, may be harassed by several landlords and landladies.

In answer to a knock one day, this doctor opened his front door to find his veranda occupied by three or four generations of Maoris. What did they want? "Money

A MAORI VILLAGE

for the rent." The lessee did not want to deal with what looked to him like a tribe, and, summoning a frown, he shouted: "Get out of here!" The rent collectors got, but outside the gate they halted, and after a parley they sent back, with better results, one of their number to collect for all.

Among Maoris land was a frequent cause of war, and it was often a bloody bone of contention between them and the white settlers. An early result of the "king movement," culminating in 1858 in the proclamation of Potatau Te Wherowhero as the first Maori king, an act that was prompted partly by a desire to retain native lands in Maori hands, was war. In this thousands of troops, including ten thousand imperial soldiers, were engaged for months. The Maoris displayed great bravery, first-class fighting ability, and remarkable cunning. The end of the war was dramatic, and typical of the Maori spirit.

In a hurriedly built fort about three hundred natives, among them women and children, for three days withstood the artillery and rifle fire and bayonet charges of fifteen hundred soldiers. When called upon to surrender, Rewi, the chief in charge, wrote to General Cameron:—

"Friend, this is the word of the Maori: They will fight on forever, forever, forever."

The women, declining an opportunity to leave the fort in safety, said:—

"If our husbands are to die, we and the children will die with them."

Finally, however, the pa's defenders dashed out in compact formation and scattered for freedom, leaving about half the garrison dead and wounded.

Of men the Maoris never were afraid, but the boldest among them quailed at thoughts of incurring the displeasure of gods and spirits. They still are superstitious, but not to the degree they once were. At all times their lives were regulated by a strict regard for the supernatural. In their memory the respected, dreaded tapu was deeply engraved in large letters. To break it often meant death. From the legendary day that the god Tanemahuta separated earth and heaven by standing on his head and kicking upward, "the whole Maori race, from the child of seven years to the hoary head, were guided in all their actions by omens."

In those days witchcraft was rampant, and persons accused of it were put to death. Curses, which were believed to be the main causes of bewitchery, were so dreaded that whole families were sometimes driven to death merely by the knowledge that they had been cursed. When a Maori believed himself to be bewitched he consulted a priest, or tohunga, who, with much ceremony, including many incantations, tried to destroy the effects of the curse.

The number of objects to which tapu applied among the Maoris was astonishing. This touch not, taste not, handle not perturber was always exercising its baneful influences. Even to those it protected it was dangerous. Also it was inconvenient. The possessors of tapu, according to an authority, did not even dare to carry food on their backs, and everything belonging to them was tapu, or prohibited to the touch or use of others. The suggestions of punishment conveyed by violations of tapu were so strong that sometimes they frightened the culprits to death.

Some forms of tapu were removable by tohungas, as those existing at the baptism of children and at tattooings. It would seem that tohungas—who, often priests, also were wizards, seers, physicians, tattooers and barbers, and not uncommonly builders of houses and canoes—had enough to do merely in lessening and preventing the results of tapu violations; but it was not so. Much of their time was spent as physicians. As such their services were required for ills both real and imaginary. Their cures were effected mainly by suggestion, and to create and convey curative fancies they employed a great variety of invocations. Also they called to their aid the properties of barks, roots, and leaves, supplemented by the planting and waving of twigs, clawing of the air, and bodily contortions. They were surprisingly successful, despite the fact that many of their cures were secured under such rigorous treatment as bathing in cold water to eradicate fever and consumption.

Tohungas did not claim ability to raise the dead, but they did undertake to revive all who were on the verge of the grave, on certain conditions. Then even the stars were required as assisting agencies. The Pleiades had to be at or near their zenith and the morning star must be seen when Toutouwai the robin caroled his first song of the day.

When the patient recovered, the tohunga was a great man. But when the patient died, there was weeping and wailing. Then it was the mournful tangi was held; then men and women came from far and near to condole with the sorrowing, to cry loudly, to feast even while their hearts were heavy and their eyes red with the deluge of many tears. Then were heard wild songs, then were seen frenzied dances, then flowed the blood of lamenting ones, usually women, who in their mad grief slashed their bodies and sometimes their faces. Sacrifices of slaves were occasionally made, that the bewailed might have attendant spirits. Sometimes even suicide was committed, as when the wives of a chief strangled themselves; and sometimes, too, wailing ones fell dead from exhaustion, and in Te Reinga joined those for whom they had so passionately mourned.

The tangi is generally observed among the Maoris even to-day. Still are heard, for days at a time, the moan, the wail, the startling outburst of pent emotion. Still tears flow copiously, noses are rubbed against each other in grievous salutation, and there are collected the great commissariat stores so indispensable where the hangi (oven) is necessary to the prolonged continuance of the tangi.

A modern tangi is a very lamentable event. The largest tangis are attended by hundreds of natives, as well as by some white men. There is food for all. When there isn't,—then it is time to stop the tangi. A tangi without food! Taikiri! Impossible! At the greatest tangis tents and specially built houses are provided for the overflow attendance. At the tangi over King Tawhiao, which was attended by three thousand persons, hundreds of tents and extra whares were erected.

After death, what? This question, in so far as it relates to rewards and penalties for deeds done in the body, would have been answered hazily by the ancient Maori. Of this phase of the world beyond, the Maori knew little. Yet he had so far progressed in religious inquiry as to recognize ten heavens and as many hells. He also believed that some souls returned to the earth as insects; and like many Caucasians to-day, he held that when persons were asleep their souls could leave their bodies and commune with other souls. His belief also embraced recognition of the Greater Existence (Io), the dual principle of nature, and deification of the powers of nature. The spirits of dead ancestors he propitiated. A possible symbol of the Maori's belief in theism I saw in the heitiki, a grotesque, distorted representation of the human form, usually composed of greenstone and hanging pendant from the necks of Maori women.