Voyage in Search of La Pérouse/Chapter 5

CHAP. V.

Port Dentrecasteaux is situated at the farthest end of Tempest-bay, and forms an almost oval basin, extending about 2,500 toises in length towards N.N.E. Its greatest breadth is about 760 toises. The tall forests that surrounded us on all sides, and the mountains at no great distance from the coast, which sheltered more than one half of the circumference of the harbour, added to the security of our anchorage. Though the gales were never so high, our pinnaces could sail about it with security. A muddy bottom, about 3½ fathoms in depth, let them run no hazard if they were driven aground. More than 100 vessels of the line might ride here with safety, and be supplied with as much wood and water as they stood in need of.

Towards the N.N.E. extremity of the harbour a small river discharges itself into the sea. Some of our boats attempted to row up the stream, but were prevented by the large trees that lay across it. A few wild dogs were observed in the neighbouring country; and some sheltering places, slightly constructed of the barks of trees, shewed that the shores were frequented by the natives. A piece of alga marina, of the species known by the name of fucus palmatus, was picked up. It was cut into the shape of a purse, and appeared to have been used as a drinking vessel, being found filled with water.

The west side of the harbour is the most favourable for taking in a supply of water. We took in ours on the W.S.W. and our wood on the opposite shore.

A fire that was seen at the distance of about 5000 toises to the South, informed us that we were near the habitations of the savages, although we had as yet seen none of them.

In the afternoon I went on shore, accompanied by the gardener and two others of our ship's company, in order to make an excursion into the country towards N.E. We were filled with admiration at the sight of these ancient forests, in which the sound of the axe had never been heard. The eye was astonished in contemplating the prodigious size of these trees, amongst which there were some myrtles more than 25 fathoms in height, whose tufted summits were crowned with an ever verdant foliage: others, loosened by age from their roots, were supported by the neighbouring trees, whilst, as they gradually decayed, they were incorporated piece after piece with the parent-earth. The most luxuriant vigour of vegetation is here contrasted with its final dissolution, and presents to the mind a striking picture of the operations of nature, who, left to herself, never destroys but that she may again create.

The trees in this forest did not grow so close together as to prevent us from penetrating into it. We walked for a long time over ground, where the water, impeded in its course, has formed itself into marshes, the borders of which we examined. Deeper within the forest, we found small rivulets that contained very good water. Almost every where the soil consisted of a very fine mould, produced by the decay of vegetables, over a bed of reddish, and sometimes greyish sand. In some places it consisted of an argillaceous kind of earth, which imbibing the water with great facility, forms itself into bogs; in others this earth has been washed away by the water filtrating through the ground, so as to form pools, and sometimes deep holes, the surface of which being covered with plants, one does not easily apprehend any danger in approaching them, but by the inadvertency of a single moment may fall into them unawares. An accident of this kind happened to the surgeon of the Esperance, who, whilst he was a-hunting, set his foot upon what he took to be firm ground, and fell into a very deep bog. He immediately disappeared; but fortunately he was able to swim.

We found some rudiments of huts in these woods, consisting of a frame-work made of the branches of young trees, and designed to be afterwards filled up with pieces of the bark, which the natives always use to cover the outside of their cabins.

I gathered several species of the eucalyptus, during this excursion; amongst others, that which White has denominated eucalyptus resinifera. This is a very tall tree, the spungy bark of which is often three inches in thickness, and separates very easily from the trunk. It produces a gum resin, of a reddish colour and astringent taste, which is used for medicinal purposes. We likewise collected several species of philadelphus, the banksia integrifolia, a new species of epacris, &c.

On the sea-shore we met the servant of Citizen Riche, greatly delighted with having shot a few birds, which he was carrying to his master. This man, who had but just recovered from a fit of illness, was still upon the list of the surgeon of the Esperance, who thought he had a right to what his patient had shot; but neither the threat of being purged, nor even that of being put upon spare diet could make him give up a single bird. The surgeon too kept his word; for he made him swallow a purgative and put him upon a spare regimen. The servant, having learnt by melancholy experience the consequences of disobeying the Doctor, always ran away as fast as he was able, whenever he espied him in any of his shooting excursions afterwards.

After having directed our route for some time to the north-eastward, we arrived before night at the coast directly opposite to our vessels. We expected to be immediately taken on board, as we had been promised that a boat should be sent to fetch us, as soon as we wanted one. This might have been done in five minutes; but we were obliged to wait two hours on the shore. It would have been a very proper regulation, if a boat had been kept expressly for the use of those gentlemen of the expedition who were appointed to make researches into natural history.

A bird that was shot upon one of the lakes, surprised us very much by the singularity of its plumage. It was a new species of the swan, of the same beautiful form, but rather larger than ours. Its colour was a shining black, as striking in its appearance as the clear white of ours. In each of its wings it had six large white feathers; a character, which I have uniformly remarked in several others that were afterwards killed. The upper mandibule was of a red colour, with a transverse white streak near the extremity. The male had at the base of it an excrescence consisting of two protuberances, that were scarcely observable in the female. The lower mandibule is red at the edges and white in the middle. The feet are of a dark grey. (See Plate IX.)

24th. It was ten o'clock of the next morning, before I could finish my description and preparation of the specimens I had collected the preceding day. I then went to examine the country situated to the eastward of our anchoring station. It frequently happened that after having penetrated into the woods to the distance of 500 toises, at most, from the shore, I was obliged to return towards the coast on account of the difficulties that obstructed my passage, which was not only impeded by the underwood, but often rendered impracticable by the stems of large trees thrown down by the wind. The direction in which they lay upon the ground, which was generally from south-west to north-east, proves that they were torn from their roots by violent south-west winds. As these trees shoot out their roots in an almost horizontal direction, they are easily torn from the ground by the force of the wind, and frequently carry with them a great quantity of earth, which at a distance appears like a wall raised by the hands of men.

The finest trees in this country are the different species of eucalyptus. Their ordinary thickness is about eighteen feet: I have measured some that were twenty-five in circumference. The spongy bark of the eucalyptus resinifera, becoming slippery in consequence of the moisture that constantly prevails in the heart of these thick forests, renders it still more difficult to penetrate into them. This bark very readily peels off into pieces that have a great degree of flexibility, and are used by the natives for covering their huts. They often find long stripes of it about a foot in breadth, which spontaneously shell themselves off from the lower part of the trunk. They might easily peel it off in pieces of twenty-five or thirty feet in length.

Most of the large trees near the edges of the sea have been hollowed near their roots by means of fire. The cavities are generally directed towards the north-east, so as to serve as places of shelter against the south-west winds, which appear to be the most predominant and violent in these parts. It cannot be doubted that these cavities are the work of men; for had they been produced by any accidental cause, such as the underwood taking fire, the flames must have encompassed the whole circumference of the tree. They seem to be places of shelter for the natives whilst they eat their meals. We found in some of them the remains of the shell-fish on which they feed, and frequently the cinders of the fires at which they had dressed their victuals. The savages, however, are not very safe in these hollow trees; for the trunk being weakened by the excavation, may easily be thrown down by a violent gust of wind; neither are their seats very commodious, as the ground is very uneven, and we observed no contrivances to render it more level. Anderson speaks of hearths of clay, made by the natives in these hollow trees. Whenever I have found any clay in them, it did not appear to me to have been placed there by the savages; but one frequently meets with it piled up between the roots in consequence of natural causes. At any rate, the natives of this country, as we shall see hereafter, do not make their fires upon hearths, but kindle them on the bare ground, and prepare their victuals over the coals.

Some of the largest trees were hollowed by the fire throughout the whole length of their trunks, so as to form a sort of chimnies: nevertheless they continued to vegetate.

Many of the large trunks that we felled during our stay at this place, were found, notwithstanding their apparent soundness externally, to be rotten at the heart.

After having followed the shore that extends with numerous windings, towards the south-east, we attempted to make our way across some marshes, in order to get into grounds that had acquired a more solid consistence from the roots of the plants; but a species of the sclerya, which grows to the height of six or eight feet, cut our hands and faces, with its leaves, in such a manner that we were obliged to desist from our attempt.

During this excursion I killed several birds of the genus motacilla, and some parrots, amongst which was the parrot of New Caledonia, described by Latham.

We now directed our route towards the entrance of the harbour, where tents had been pitched for the purpose of taking observations, as we were sure of meeting there with a boat to carry us on board.

The astronomers expected the first of Jupiter's satellites to appear at about a quarter of an hour after eight in the evening; but with all their activity they could not get their instruments ready in due time; so that the opportunity was lost. Bonvouloir, one of our officers, who had made the preliminary calculations a long time since, was so affected by this disappointment, that he wept like a child.

One of our crew shot a young kangarou upon the shore. The animal, after running about a hundred yards along the sand, threw himself into the sea and expired. It was remarkable that he used all his four feet in running, not supporting himself solely upon the hinder feet, as he is usually represented to do; though these as well as the fore, are without hair on the inner side. As he goes in quest of his food more in the night-time than during the day, nature has provided him with the membrane termed by zoologists membrana nictitans, situated at the interior angle of the eye, which he can extend at pleasure over the whole ball. His stomath was full of vegetables, and divided by three very distinct partitions, which seem to approach him to the class of the ruminant quadrupeds. His testicles were on the outside of the abdomen. These animals probably find a part of their food on the sea-coast, as we frequently observed the prints of their feet in the sand.

25th. Having left some of my plants in the hands of the painter, that he might take a drawing of them, I followed the windings of the coast in a south-east direction. The large slippery pebbles which covered the strand were a great impediment to us in walking.

We found on the skirts of the forest a fence constructed by the natives against the winds from the bay. It consisted of stripes of the bark of the eucalyptus resinifera, interwoven between stakes fixed perpendicularly into the ground, forming an arch, of about a third of the circumference of a circle, nine feet in length and three in height, with its convex side turned toward the bay. A semicircular elevation covered with cinders, and heaped round with shells, pointed out the place where the natives dressed their victuals. Such a fence must be of great service to them to prevent their fires being extinguished, when the wind blows with violence from the sea.

Having crossed a promontory of the coast, we walked with difficulty over the loose sands, which cover a large tract of land, that sometimes lies under water.

We found another of the fences above described on the skirt of the forest. It was of the same construction and height as the former, but twice as long. Within it were broken pieces of drinking vessels made of the fucus palmatus.

We arrived at the borders of a lake, which is connected with the sea at flood-tide. Its greatest length was 750 toises, and its breadth 250.

On our return by a more direct road through the woods, we saw some unfinished huts of the natives. They consisted of branches fixed by both ends into the ground, and supported the one upon the other, so as to form a frame-work of an hemispherical form, about four feet and an half in height. The branches were fastened together with the leaves of a species of grass; and the buildings seemed to require nothing more in order to be completed, than to receive their coverings of bark, which renders them impenetrable to the rain.

It seems that human beings are here either very few in number or in a very savage state. Though a great number of the men from both vessels had penetrated very far into the country, they had not met with a single inhabitant.

The Cape of Van Diemen is subject, in consequence of its high latitude, to very violent winds, which blow from the mountains in blasts. Fearing that our cables might rot upon the muddy bottom of this harbour, we had taken them on board and held on our chain. A sudden and violent gale from N.W. drove us from our anchorage, to the east side of the harbour, where we ran aground in the mud. After having drawn in the piece of cable to which the chain was fastened, we found that one of the links had been broken; though upon examining it we could not perceive any flaw in the iron. It appeared that the chain had been made of brittle metal. We thought it fortunate that it had been put to the proof in a harbour, where we ran no other danger than that of being stuck in the mud; otherwise this chain, upon which our safety depended, would have become the cause of our ruin.

26th. I remained the whole day on board, employed with preparing and describing the numerous curiosities of natural history, which I had collected on the preceding days.

On the following day, soon after dawn, we set out with a design of penetrating as far as we were able into the country. We were set on shore towards S.E. After having followed the windings of the shore for some time, we came to a road frequented by the natives, which enabled us to enter the forest in a south direction. We afterwards arrived at a fine sandy beach, extending about 1000 toises in the same direction.

A beautiful species of erigeron, the woody stem of which is covered with very small bulbous leaves, grew in this dry ground. Though there was very little wind, the waves broke with violence over a great extent of the beach. We regularly observed that, after three successive waves, one much larger than the rest followed and broke higher upon the beach, so as to oblige us to keep further off from the shore.

On a small rising ground of the coast, I found the species of the banksia, denominated by Gærtner banksia gibbosa. Whilst we were journeying through the forest, at a small distance from the shore, one of our company observed a young savage, who was running away affrighted by a shot which had been fired at a bird. As soon as we were informed of it, we all ran in pursuit of him, being very desirous of having an interview with some of the natives. But all our search was in vain; for the young savage had disappeared by rushing into the thickest of the forest at the risk of tearing his skin; for he was stark naked. We found one of the fences against the sea-winds at the place where he had been first seen.

The hope of meeting with some of the savages determined us to penetrate farther into the forest, with a resolution to pass the night there. We walked for the space of an hour towards the south-east, over a very rugged path, before we arrived at a large plain that extended as far as the sea-shore. A beautiful species of the mimosa grew here, with long oval leaves, and generally about twenty-five or thirty feet in height.

Night compelled us to look out for a place of shelter. We could not have recourse to the cavities burnt in large trees by the natives, as we were too far distant from them: we therefore constructed a hut of branches, which we had lopped from the trees with a pole-axe that one of our company carried with him for his desence. The hardness of the ground was meliorated with a bed of fern, of a species very nearly resembling the polypodium dichotomum.

Being close to the shore, we had a very extensive prospect, but observed no signs of the natives being near us. We kindled a fire as the weather was very sharp.

We were not altogether easy with respect to our means of subsistence; for when we lest the ship we had furnished ourselves with but one day's provisions; but as sailors are used always to take some sea-biscuit with them when they go on a journey, those who accompanied us were still provided with some of it. With this stock of eatables, our most necessary requisite was water, which we were obliged to send for to a distance of 1000 toises. Such a supper as this certainly required a good appetite.

As we were seven in number, we had not much to fear from the natives. We however settled it that every one should stand upon watch in his turn, that we might be informed of their motions in case any of them should come near us.

The severity of the cold obliged us to quit our hut and lie down to sleep round the fire.

28th. As soon as it was day we went out with our guns, to endeavour to shoot something for our breakfast. We soon killed a couple of rooks, which were immediately broiled and eaten, as if they had been the most delicate food.

We had been obliged to reduce ourselves to a very moderate allowance on the preceding evening, that we might have means of subsistence for the following day; but we found, when it was too late, that the person to whom we had intrusted the care of our provisions, was not to be depended upon, for of the six biscuits that had been committed to his charge, only four were left. Had he carried his breach of trust a little farther, we should have been obliged to return to the ships immediately, with the mortification of being compelled to relinquish our intended researches.

We soon arrived at the borders of a large lake, connected with the sea by a channel about 120 feet in breadth. We attempted to ford it, but it was too deep about the middle.

Amongst a great variety of other plants that grew in the neighbouring woods, I observed several species of a new genus of the pedicularia, very nearly resembling the polygala. Amongst the shrubs which ornamented the grounds near the shore, was a beautiful species of sensitive plant with simple leaves, the stalk of which was bent into the form of the letter S.

We saw a large flock of black swans sailing upon the lake; but they were not within reach of our guns. Some small islands were visible towards S.E. near the opposite shore of the lake. We killed a number of snipes of different kinds while we directed our march towards S.W. in order to arrive at the farthest extremity of the lake. The bottom of the lake is here so even, that throughout a surface of more than fifty toises in length, the water is hardly more than a foot and an half deep. It is covered with a prodigious quantity of shells, many of which are decayed in consequence of the length of time they have lain there.

Black Swan of Van Diemen's Land

The crista marina is found upon these shores. I discovered at a little distance from them a new species of parsley, which I named apium prostratum, on account of the position of its stem, which always creeps along the ground. Its analogy with the other species of the same genus, led me to think it might be good to eat, and it answered my expectations. We carried a large quantity of it on board with us, which was acceptable to mariners who felt the necessity of obviating, by vegetable diet, the bad effects of the salt provisions on which we had lived during the whole of our passage from the Cape of Good Hope to that of Van Diemen.

Cretin, one of the officers of our ship, together with the engineer, had been sent with the longboat by our Commander, in order to reconnoitre Tempest-bay. They brought intelligence at their return, after having advanced fifteen or twenty thousand toises into a channel which we had left on our right when we entered the bay, that every appearance concurred to make it probable that this was a strait. Wherever they had sounded they found very good anchorage ground.

29th. I was very little on shore during the two following days.

30th. The whole forenoon I employed in describing and preparing the copious collections which I had made on my last excursion. In those parts of the country which I examined in the afternoon, I found several plants of the tribe of orchis, some of which I gave to be copied by the painter.

The fishing nets were regularly sent out every evening, and abundance of fish was taken. The meals we now made on board contrasted very strikingly with those we had been obliged to put up with during our passage.

I must here remark, that those of our company who were engaged in the pursuit of natural history, were not permitted to take with them, on their excursions, the smallest quantity of that allowance of fresh provisions which we claimed as our right: ship's biscuit, cheese, brandy, and sometimes a little salted bacon, was all that was provided for us. The reasons we alledged were sufficient to evince the justice of our demand; nevertheless, we had no other provisions allowed us on these occasions, during the whole course of our expedition. I should have passed over this circumstance in silence, had I not thought that it might afford a useful hint to persons employed in the same pursuit, who may hereafter be engaged in such expeditions.

May 1st. I resolved to examine the other coast of the harbour to the eastward. The bottom was here so shallow, that we could not come close to the land with our boat, so that we were obliged to wade part of the way in the water.

I followed the coast in a northerly direction, sometimes penetrating a short way into the forests. As it was low-tide, I walked with great facility along the shore, where I observed several small holes, in the form of a tunnel, made in the sand, each of which contained a small crab at the bottom. Upon drawing out the animal, it soon crawled back into its hiding place, which, as I judge from its analogy with that of the formica leo in our country, serves it likewise as a trap to catch its prey.

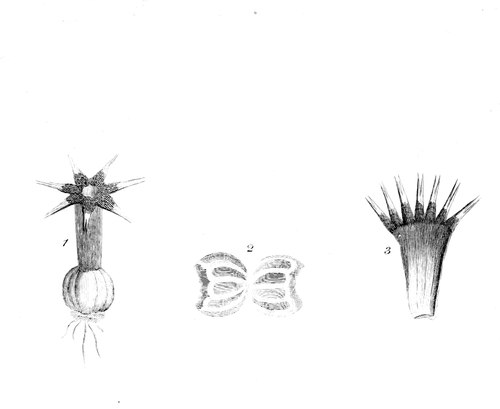

I was agreeably surprised by the singular form of a new species of fungus, which grew amongst the mosses with which the ground was covered. I named it aseroë, on account of the disposition of its radii.

Its roots are small filaments attached to a fungous tubercle, which supports a globular volva, of a whitish colour and gelatinous consistence, marked both within and without with seven striæ.

From the centre of this volva proceeds a stipes of a reddish colour, and an almost cylindrical form, hollow throughout, and open at its superior extremity, which forms a sort of cup, of a fine red colour, and divided into seven bifurcate radii, yellow at their extremities. The whole surface of this fungus is smooth.

This new genus ought to be placed next in order to the genus phallus of Linnæus.

Explanation of the figures in Plate XII.

Fig. 1. The fungus.

Fig. 2. A transverse section of the volva, shewing its interior parts.

Fig. 3. A longitudinal section of the stipes.

The declivities of the mountains situated to the eastward, form a pleasant valley, from whence the waters, collected there by the union of a great number of small streams, are discharged into the bay. By washing the stems of the large trees which cover the country, through which it flows, the water acquires a brownish tinge. The closeness of the shrubs, and the marshes which occupy the low grounds of this valley render it very difficult of access. We were, however, resolved to attempt it at the risk of sticking fast in the mud; but were often stopped in our progress, by a new species of the scleria, to which I gave the name of scleria grandis, as it frequently grows to the height of twelve feet. Its leaves are as sharp at the edges as a piece of glass; its berries are oval and of a reddish colour, and contain a sort of almond,

|

1. Aseroe Rubra |

|

4. Spider which the Caledonians eat.

The most common shrub in these low grounds was a new species of the embothrium, remarkable for the hardness of its leaves. These leaves are of an oval form, three inches in length and one in breadth.

We followed a very difficult path, in order to arrive at the place where our men were taking in water. Night overtook us before we had finished more than half our journey, and to add to our misfortunes, a very high wind from the west brought with it such a heavy rain, that we were obliged, like the savages of New Holland, to seek for shelter in hollow trunks of trees. We had reason to apprehend that the signals we made for a boat to come to fetch us, would be rendered useless by the rainy weather, and were beginning to make preparations for passing a very unpleasant night in the midst of the forest; when we heard the voices of some sailors who were sent to fetch us on board.

They had at length succeeded in extricating the anchor to which the chain that was broken on the 25th of April had been fastened. The drag had been used in vain as the chain was sunk too deep into the mud. The hold of the anchor in the ground was so strong, that the two long boats lashed together were repeatedly filled with water whilst they were hauling at the buoy-rope. Besides, it was sunk so deep, that the divers could not find its bill: it would have been better if the main capstan had been used. They then became sensible of the necessity of doubling the buoy-rope and heaving the anchors from time to time, to prevent them from sinking too deep in the muddy bottom.

Two boats had been sent a second time to reconnoitre the north-east side of Tempest-bay, as far as Cape Tasman. They returned at the end of four days, and it appeared to result from their observations, that Tasman's head-land and the coast of Adventure-bay made part of an island separated from Van Diemen's land by the sea. After they had gone up the channel as far as 43° 17′ S. lat. they were obliged to return for want of provisions.

2d. My occupations on board did not permit me to go far into the country.

3d. On the following day we traversed a glade that extended in a north-east direction, and conducted us to the great lake. We had examined the southern side of it in a former excursion, but we wished still to visit its northern coast, the various situations of which gave us reason to expect an abundance of natural curiosities: nor were our hopes deceived. This coast was in many places formed of high banks, very difficult of access: the water frequently extending as far as the foot of the hills. Different species of mimosa, with simple leaves, grew under the shade of the large trees.

It appears that the natives sometimes fix their habitations upon the borders of this lake, which affords them abundance of food in the shell-fish it contains. We found a hut which they had built a few paces from the shore, of a semi-oval form, about three feet and three quarters high, and four feet broad at the base. It consisted of branches fixed at both ends into the ground and bent into a semi-circular form, supporting each other, so as to form a pretty solid frame-work, which was covered with the bark of trees.

Amongst a number of other curious plants which I collected, I was struck with the beauty of the flower of a new species of aletris, remarkable for its bright scarlet colour.

As the season was already far advanced, we found very few insects.

Some hours before sun-set we directed our course to the south in order to return to our ships; but it was already dark before we arrived at a sandy beach that we were acquainted with. We were still at a great distance from the ships, and it was not before half an hour after nine o'clock that we arrived at the tents of observation, from whence we were soon conveyed on board.

5th. I remained on board during the greater part of the two following days, and employed myself with stuffing the skins of a variety of rare birds, and describing the natural curiosities which I had collected.

The want of room in our vessel put me under the necessity of drying the plants, which I had preserved in paper, at the fire. As my cabin was already full, I had no other place where I could deposit some of my specimens of plants that had not got perfectly dry than the great cabin. Dauribeau, who acted as first lieutenant, thought that this place ought not to be lumbered with such useless things as natural curiosities, and ordered my two presses, with the plants they contained, to be turned out. I was obliged to appeal to the Commander, who annulled this act of authority, and ordered that the presses should remain where I had placed them.

At low water we sound a variety of curious shells on the shore. This harbour afforded us great plenty of very fine oysters.

The east coast of the harbour contained a quantity of pyrites in crystals of various forms. We likewise observed large masses of silex in very close strata, which bore a great resemblance to petrified wood.

One of our carpenters killed an amphibious animal of the species known by the name of phoca monachus, about six feet in length.

Physiologists have explained in a very ingenious manner how amphibious animals are enabled to remain so long under the water by means of the foramen ovale; but, upon examining the heart of this animal with the utmost attention, I did not find that it had any foramen ovale. Probably the same may be the case with many other amphibious animals. By pursuing these researches we may one day discover the true cause of the astonishing faculty possessed by these animals, of living equally well both in the air and in the water.

Each side of its lungs is divided by a transverse fissure into two lobes.

The stomach, which resembles in shape very nearly that of a hog, contained a large quantity of calcareous sand, amongst which I observed several shell-fish that were still entire. The first part of the function of digestion in this animal seems to consist in destroying the shell in which the fish is enclosed, whereby a quantity of sand is produced in its stomach, which does not appear to pass through the rest of the intestinal canal, but is probably disgorged in the same manner as many snakes disgorge the bones of the animals on which they feed. Possibly too this sand may serve them as a sort of ballast, by which they are enabled to keep themselves at the bottom of the sea.

As the food upon which they live is very easily found, their mouth is formed with a very small orifice. As they live more in the water than in the air, they require a great power of refraction in the humours of the eye; whence the vitreous humour is found to be very dense. They are likewise provided with the membrana nictitans, whereby they are enabled to admit a greater or lesser quantity of light to the eye at pleasure.

The great variety of my other occupations did not permit me to pursue these anatomical investigations any farther.

The dried excrements of this animal produce a very fine powder of a deep yellow colour, which our painter thought might be used with advantage in the arts.

6th. I had not as yet been able to procure any of the flowers of a new species of the eucalyptus, remarkable by its fruit, which very much resembles a coat-button in shape.

This tree, which is one of the tallest in nature, as it grows sometimes to the height of 150 feet, blossoms only near its summit. Its trunk exactly resembles that of the eucalyptus resinifera, when its spongy bark has been peeled off. In other respects these two species are nearly of the same dimensions. The trunk, which is very straight, at least to one half of its height, might be usefully employed in ship-building, and especially for masts, although it is neither so light nor so elastic as that of the fir. Possibly it might be of advantage to construct masts of different pieces of timber, and even to perforate the large trunks of trees throughout their whole length, so as to render them lighter, and to give them strength by binding them at equal distances with hoops of iron. By this means, I should think, they might be rendered as strong as one could wish; since persons versed in mechanics know that a cylinder, though hollow, still retains a great degree of strength.

We were obliged to cut down one of these trees in order to obtain its blossoms. Being already in a very slanting position, it was easily felled. As the sun shone very bright the sap was mounting in abundance, and as soon as the tree was cut down it flowed very copiously from the lower part of the trunk.

This beautiful tree, which belongs to the tribe of the myrtles, has a very smooth bark; its branches are somewhat crooked, and have towards their extremity alternate leaves, slightly bent, and about six inches in length, and one-half in breadth.

The flowers are solitary, and grow from the base of the stalk of the leaf.

The calix is shaped like an inverted urn, and consists, like that of the other genera of the same tribe, of a single leaf, which falls off as soon as the stamina are completely formed.

It has no corolla.

The stamina are numerous and attached to the sides of the receptacle.

The style is simple and divided at its base into four partitions. It has only one stigma.

The capsule is open at the top, and generally divided into four partitions, which contain a number of angular seeds; at the base it has four angles, two of which project more than the rest. It is shaped like a button; on which account I have denominated this tree eucalyptus globulus.

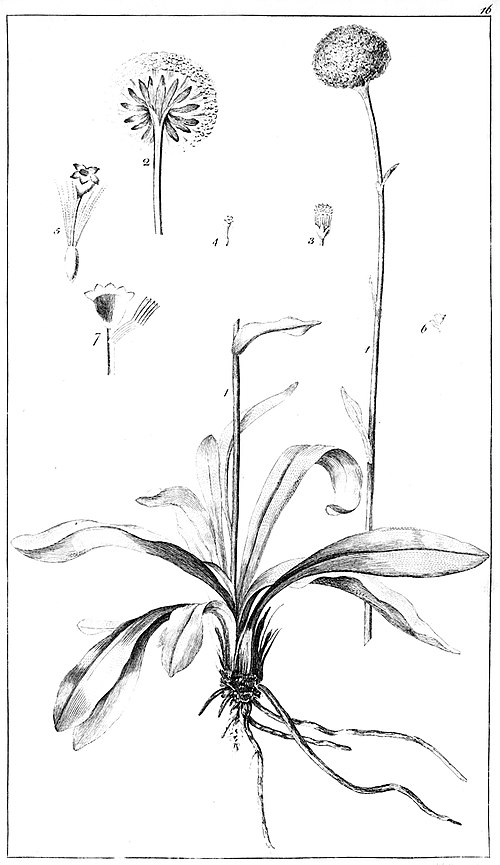

Explanation of the Figures in Plate XIII.

Fig. 1. Branch of the eucalyptus globulus.

Fig. 2. Flower.

Fig. 3. Fruit.

Fig. 4. Calix.

The bark, leaves and fruit of this tree are of

Eucalyptus Globulus an aromatic nature, and might be employed for economical uses in the place of those aromatics with which we have hitherto been furnished exclusively by the Molucca Islands.

On the seventh, I was obliged to employ almost the whole day in preparing my collections, which accumulated prodigiously from day to day. I could therefore extend my researches only to a very small distance from our anchoring-station. But on the following day, I set out in the afternoon with a design of spending three or four days in the woods without returning at night to the ships. I was obliged to take this resolution in order to collect specimens of such plants as only grew at a considerable distance from our station.

We had a great variety of different kinds of European grain on board, which might be advantageously propagated at this extremity of New Holland. The temperature that generally prevails in this country led us to hope that they would succeed. Our gardener was directed to prepare a spot of ground so as to render it fit for receiving this deposit. He dug a small garden for this purpose on the east coast of the harbour, situated E.N.E. of our place of anchorage.

We slept on the banks of a rivulet near the western extremity of the great lake, along the southern coast of which we directed our route on the following day. We saw some pelicans; but they did not come within gun-shot of us.

Piron, the painter to the expedition, who was of our party, took several drawings of the landscape. The round hills, covered with tall trees, which bounded the horizon added greatly to the beauty of the prospect.

We were obliged to return back by the road we had come, in order to arrive at the opposite side of the lake. Piron returned on board.

I discovered an evergreen tree, which has its nut situated, like that of the acajou, upon a fleshy receptacle much larger than itself. I therefore named this new genus exocarpos.

It has hermaphrodite flowers upon the same peduncle with others which are distinctly male and female.

The male flowers have a calix divided into five roundish leaves; they have no corolla; the stamina, which are five in number, are small and attached to the calix between its divisions; the germen abortive.

The female flowers have a calix similar to that of the male; but neither corolla nor stamina: the ovarium is globular, with a short style; the stigma circular and flat.

Exocarpos Cupressiformis In the hermaphrodite flowers, the calix, stamina and ovarium are as I have described them in the others.

The fruit is a nut of an almost spherical form, and of a blackish colour, placed upon a receptacle, fleshy, red, divided in the middle, and about three times as large as the nut.

The kernel is of an oily nature, and of the same shape with its shell.

The principal characters of this plant have led me to rank it among the terebinthinaceous tribe, next to the anacardium. I have given it the name of exocarpos cupressiformis.

Explanation of the Figures Plate XIV.

Fig. 1. A branch of the exocarpos cupressiformis.

Fig. 2. Portion of a branch in flower.

Fig. 3. Germen, with its style and stigma.

Fig. 4. Fruit.

Fig. 5. The fruit divided longitudinally, shewing a cavity in the middle of the fleshy peduncle.

Fig. 6. The nut.

Fig. 7. Part of the woody substance surrounding the nut.

Towards the close of the evening we arrived at the banks of a rivulet, where we fixed our place of abode for the night. I observed at this southern extremity of New Holland several species of ancistrum, analogous to those found at the southernmost extremity of America.

We were surrounded with pleasant groves, consisting for the greater part of a beautiful species of thesium with strait leaves.

The cold had obliged us to kindle a large fire. Some of us were scarcely beginning to fall asleep, when we suddenly heard the cry of a beast of prey at a few paces distance. Our fire had probably been of greater service to us, in preventing this animal, which from the sound of its voice we believed to be a leopard, from approaching nearer, than we should have expected when we kindled it.

I had found, on one of the preceding days, the upper jaw-bone of a large animal of the carnivorous tribe.

10th. As soon as the day appeared, we continued our journey on the borders of the lake. At a very small distance from the coast we observed five islands covered with trees, which formed an agreeable contrast with the level surface of this vast sheet of water.

We perceived, for the first time in this country, several quails that flew at a great distance from us.

After marching for several hours towards the north-east, we found upon a small hill, under the shade of some very tall trees, two huts of the same construction with those we had seen before. They were in perfectly good preservation, and seemed to have been lately inhabited.

I discovered a very beautiful plant, which forms a new genus very distinct from any that has hitherto been described. It resembles the iris, but has only two stamina. On account of this singularity, I gave it the name of diplarenna, and on account of its affinity with the genus moræa, I called it diplarenna moræa.

The spatha has two partitions, and incloses several flowers, which leave it one after the other when they are ready to blow. They fade much sooner than those of the iris and moræa, so that I should have given up all hopes of having them copied, if new ones had not followed the others which withered almost immediately after I had plucked the plant from the ground.

Like the iris, it has no calix.

The corolla has six petals, three of which are interior, and much smaller than the exterior: of the three interior petals, the superior is rather smaller than the rest, and more inflated towards the base.

Upon examining a great number of the flowers, I have uniformly found that they contain only two stamina, the filaments of which terminate in a point supporting antheræ of a white colour, and marked with two fissures. In the place of a third stamen, I have only found a small filament, without any antheræ, situated between the superior interior petal.

The ovarium is inferior. It has three angles, and is supported by a long peduncle.

The style is a little longer than the stamina, cylindrical, and terminated by a stigma shaped like a shepherd's crook.

The capsule has three partitions, containing several spherical seeds, which are fixed to a receptacle that extends from the middle of the partitions to the top.

This genus, which naturally ranks after the iris and the moræa, has all the habitudes of those plants. Its leaves are of the same sword-like form, with their edges compressed near the base.

Explanation of the Figures in Plate XV.

Fig. 1. The plant.

Fig. 2. The flower-buds displayed by cutting away the spatha. A full-blown flower with the three exterior petals torn off.

Fig. 3. An exterior petal seen from its inner surface.

Diplarrena Moræa Fig. 4. The same petal seen from its outer surface.

Fig. 5. Interior petals turned down, to give a view of the stamina and style.

Fig. 6. The stamen seen through a magnifying glass.

Fig. 7 The style with its stigma.

Fig. 8. A part of the germen, the stamen and style having been taken away, in order to shew the small filament, which is found in the place of a third stamen.

Fig. 9. Lower half of the capsule divided transversely, to shew the three partitions.

Fig. 10. Upper half of the capsule divided longitudinally, to shew the seeds.

As we were walking through a small grove, where the underwood grew very thick, I roused a large kangarou at a very small distance from me. He immediately ran a length of about thirty paces through one of those narrow paths which these animals make for themselves through the thicket, where they are obliged to use all their four feet, as they have no room for an erect posture; and having reached the farther end, bounded away over the bushes with such swiftness, that we soon lost sight of him.

We found a sheet of water covered with a prodigious number of wild ducks, which flew up when we were quite close to them; but we were so little prepared for such good fortune, that we were not able to kill a single bird.

A high wind sprung up towards night, which seemed to threaten rain. As we had no place of shelter near us, we were obliged to sleep in the open air. We constructed a fence against the wind with branches, under shelter of which it was easy to kindle a large fire.

11th. On the following day we directed our course eastward, and traversed a vast plain, beset in many places with marshes, where the plants with which they are overgrown conceal the danger one is exposed to in passing through them. The water collected in the lowest situations gives rise to a number of very fine rivulets.

A very large kangarou sprang out of a bush about four paces from me. I pointed my gun at him, but it missed fire, and the animal walked off very composedly, following one of those tracks through the thicket which they usually frequent. These tracks are covered passages which cross each other in every direction, and run very close one to another. The numerous prints of the feet of those quadrupeds observable upon them, shew that they abound in this country. The best way of catching them would be to hunt them with dogs, as they generally keep themselves in the thickest part of the woods. Their tracks generally terminate at some rivulet.

Having exhausted our stock of provisions, we were compelled to endeavour to reach the ships before night. We wandered about the woods a long time before we arrived at the north-east extremity of the harbour, from whence we had a distant view of our vessels. It was not without great difficulty that we reached the place where they rode at anchor, as we had to pass through many very rugged grounds.

12th. The whole day was hardly sufficient for me to prepare and describe what I had collected on our last excursion.

Having left some of my specimens which could not be preserved without being daily attended to, in the care of one of the servants, who remained on board during my absence; I had the satisfaction to find them in good condition.

Citizen Riche found some human bones amongst the ashes of a fire made by the natives. Several bones of the pelvis he discovered by their form to have been part of the skeleton of a young woman: some of them were still covered with pieces of broiled flesh. I am, however, scrupulous of ranking the natives of this country with the cannibals: I rather suppose that they have the custom of burning the bodies of their dead; as these were the only human bones that were seen during the whole of our abode in this place.

On the 13th I went to the place where our men were taking in their water. It was furnished by a small rivulet, which discharges itself into the harbour, after flowing amongst the trunks of fallen trees with which the country is covered. The rotten wood gives the water of this rivulet a brownish tinge. They were obliged to roll the casks upwards of a hundred yards to the boats, as these could not come nearer to the shore on account of the shallowness of the bottom.

We found the carpenters employed in raising the sides of our pinnace, which had shortly before been overset whilst it was sailing in the harbour. The crew had been obliged to save themselves by swimming till assistance was brought them. It had been furnished with too high a mast, and much too large a sail, by the lieutenant, who ought to have understood the proportions better.

The wood made use of by the carpenters was that of the new species of the eucalyptus, which I have denominated eucalyptus globulus. They thought it very good timber for ship-building.

A perpetual moisture prevailed in the thick forests into which I penetrated towards S.W. Mosses and ferns of various kinds grew there with great luxuriance. I killed a bird of that species of the merops, which White has denominated the wattled bee-eater, and of which he has given a very good engraving. It is remarkable for its two large excrescences on each side of its head.

I was obliged to make great haste in preparing the skins of the birds which I wished to preserve; for the flesh, when exposed to the air, very soon became full of small living larvæ, deposited in it by a fly of a reddish brown colour, which is viviparous like that of our country, known by the name of musca carnaria. These larvæ accelerate the putrefaction of flesh in a surprising manner.

As we intended to weigh anchor on the following day, I wished to make the best use of the last moments of our stay in this place, and went on shore at the easterly coast nearest to our vessels.

I visited, in company with the gardener, the spot where he had sown different kinds of European grains. It was a plot of ground of twenty-seven feet by twenty-one, divided into four beds. The soil was rather too full of clay to insure the success of the seed.

When we had entered the woods, a quadruped of the size of a large dog sprang from a bush quite near to one of our company. This animal, which was of a white colour spotted with black, had the appearance of a beast of prey. There can be little doubt that these countries will at some future time add several new species to the classes of zoology. A spinal vertebra, that was found in the interior part of the country, the body of which was about four inches in diameter, gives reason to believe that very large quadrupeds will some time be discovered here.

A very heavy rain, which overtook us about the middle of the day, obliged us to halt. We sheltered ourselves in the hollow trunk of a large tree that was upwards of twenty-four feet in circumference. We attempted to kindle a fire in it after the manner of the New Hollanders, but the smoke soon drove us from our retreat.

We endeavoured to penetrate into parts which we had not yet visited. A glade, at which we arrived, seemed to conduct us towards the north-east plain. We had only three hours of the day before us. A steep ascent impeded our journey, large trees heaped one upon another obstructed the path, and the shrubs, to which the moisture that prevails in these forests, give an uncommonly luxuriant growth, increased the difficulties we had to encounter. Amongst these shrubs was a beautiful species of polypodium, the stem of which grows to the height of twelve feet.[1]

Towards close of evening we found ourselves on the borders of the lesser lake. The woods that surrounded it did not permit us to follow it dry-shod in all its windings: the water through which we had to wade was, fortunately, not very deep. Notwithstanding the darkness of the night, I discovered a new species of restio, which I had never seen before.

This lake, though it is connected with the sea at high water, does not abound with fish. Some of the crew of the Esperance had been here, with their nets, but caught nothing.

Having reached the sea-shore, we had still a considerable part of our march before us. It was night, and the thick clouds increased its obscurity. Sometimes we were obliged to pass over large blocks of rounded stones washed by the surge. We groped our way along the shore, at the hazard of falling into the sea, and it was with great difficulty that we were able to support ourselves on our feet amongst the wet stones, that were rendered still more slippery by being covered with fucus and other marine productions.

A great number of phosphoric animalcules, of different sizes, were driven on shore by the waves, and afforded us the only light we had to direct our steps.

At length we arrived at the place where the tents had been pitched for taking astronomical observations. We found nobody there, as the instruments had already been carried on board.

Our master sail-maker having gone the preceding day on a shooting excursion, without any companion, had lost his way in the woods, where he was obliged to spend the night. Several guns were fired to let him know where the ships lay at anchor; and in the afternoon he returned on board emaciated with hunger and fatigue. Having set out without any provisions, he had been a day and an half without food. He related, that during the night several quadrupeds had come to smell at him, within a few inches distance. Many of the crew believed him on his word; but we, who had spent several nights in the woods, and had never met with such familiarity from the beasts, were not so credulous; but far from imagining that he wished to impose upon us, we found, in his narrative, the natural effects produced upon the imagination of a man deprived of nourishment, and all alone in the midst of immense and pathless forests.

15th. On the preceding day the large anchor had been drawn up and a smaller one moored, that we might be able the sooner to leave the harbour. The same had been done by the Esperance. Some sudden blasts from the north-east, during the night, drove both ships from their anchors and ran them aground in the mud. They, however, suffered no damage, and were easily set again afloat. It was surprising that they should have thought themselves secure with one small anchor, but just moored in a muddy bottom, as this sort of bottom affords very little hold till the anchor be sunk to a considerable depth.

We only waited for a favourable wind to leave the harbour. During the whole day it was contrary, and in the night time it blew with great violence. Dauribeau, however, although we had ran aground only the night before, thought it sufficient to moor a single cablet; but his opinion was over-ruled by the rest of the officers, who knew, from experience, the necessity of holding by the large anchor.

During our abode at the Cape of Van Diemen we had only seen the natives at at a considerable distance; those who had observed us having always fled with great precipitation. Some of them left behind them their househeld utensils, which gave us a very imperfect specimen of their industry. These were baskets, clumsily constructed of the reeds known by the name of juncus acutus, and drinking vessels, made of a large piece of fucus palmatus, cut into a circular form, and moulded into the shape of a purse. We never found any weapons of defence in the places from whence they had fled: no doubt, they either carried them away, or carefully concealed them, for fear that we might employ them against themselves.

These scattered huts indicated a very scanty population; and the heaps of shells which we found near the sea-shore, shewed that these savages derive their principal means of subsistence from the shell-fish which they find there. As we only once discovered human bones in this country, and those partly burnt, it appears that they do not expose the bodies of their dead to the open air. It is difficult to know whether it be their usual custom to burn them: possibly they bury them in the earth, or throw them into the sea.

The great number of tracks marked with prints of the feet of quadrupeds, shew that they abound in this country. They probably remain during the day-time in the thickest part of these inaccessible forests.

A great number of small rivulets discharge themselves into the harbour. The ground was here so full of moisture, that wherever a hole was dug of a moderate depth, it immediately became filled with water.

We generally took copious draughts of fishes with our nets; especially when the east and south-east winds drove them into the bay.

Van Diemen's land was discovered by Tasman in the month of November, 1642. When Captain Cook anchored here four years after Furneaux, in the year 1777, he thought himself the third European navigator who had been upon this coast. Cook did not know at that time that Captain Marion, after having remained here for some time, sailed from thence on the 10th of March, 1772. The natives conducted themselves in a very different manner to these two navigators. Possibly the gentleness with which they behaved to Captain Cook, might be an effect of their terror for European fire-arms, of which they had received an idea from Marion's having been under the necessity of using them against them.

The place of our observatory, situated near the entrance of the harbour to the right of the vessels, was 43° 32′ 24″ S. lat. 144° 46′ E. long.

The variation of the magnetic needle was 7° 39′ 32″ E.

The inclination of a flat needle was 70° 30′.

The tides flowed only once a day. The time of high water in the harbour at full and change days, was between nine and twelve o'clock, the water rising about six feet perpendicular height. The tides were very much influenced by the winds, which often advanced or retarded them by several hours.

The sheltered situation of this harbour, renders it the most commodious in the world for vessels to put into in order to be repaired. The vast forests, with which it is surrounded, furnish a timber which our carpenters considered as very proper for ship building, and which they employed with great advantage.

During our stay of nearly a month at this place, the weather was very unfavourable for making astronomical observations. The season of the year was likewise not an eligible one for investigating these coasts, which was rendered still more difficult by the violence of the winds.

Whilst we remained at the Cape of Van Diemen, the north-west and south-west winds were very violent: the former were generally attended with storms and heavy rains.

As soon as it was day the vessels were towed to the mouth of the harbour, from whence we sailed with a north breeze towards the new strait, which we intended to enter.

After ranging along the windings of the reef, which we had left on our larboard side when we entered Tempest-bay, we were at ten o'clock in the forenoon at the distance of about 7,600 toises from the entrance of the strait, which bore N.N.W. when we trimmed our sails as sharp as possible.

The summits of the highest mountains were already whitened with the snow. These mountains form part of a chain which extends from south-east to north-west, and terminates near the farthest extremity of the harbour.

We were much gratified in viewing, from the ship, the places which we had lately visited in our excursions.

At one time we observed a thick smoke ascending from the distant country to the northward of the great lake, and soon descried five of the natives walking away from a fire which they had just been kindling on the shore: one of them carried a fire-brand in his hand with which he lighted the flames in different places, where the fire presently caught and was almost as soon extinguished.

We plied to windward, keeping in with the coast; as we had no danger to apprehend from approaching it.

A slight breeze from the north, as well as the tide, being against us, we could not enter the strait before night. We therefore cast anchor at the mouth of it, in a bottom of grey sand, at the depth of 30 fathoms. The place where we had pitched our tents of observation was then at the distance of about 10,000 toises to the westward.

The mercury in the barometer having been gradually falling for the space of four and twenty hours, remained stationary at 27½ inches, though the sky appeared still very clear. We were not without some uneasiness, as so great a variation in the barometer had never failed during our stay in the harbour to be followed by violent winds. Probably such blew at a distance, but we experienced none of their effects. During the night we saw a fire to the west, kindled by the natives.

17th. The current having become favourable about nine in the morning, we weighed anchor with a northerly breeze, and plied to the windward.

We were near enough to the coast to be able to perceive at the entrance of the strait a sort of free-stone, similar to that found in port Dentrecasteaux.

The snows had increased prodigiously upon the summits of the high mountains, during the preceding night.

The mercury in the barometer had sunk to 27 inches 4 4-10th lines, though the breeze from the north still continued slight.

It was night when we entered the strait to which we gave the name of our Commander, Dentrecasteaux. About seven o'clock in the evening we cast anchor in a bottom of blackish mud mixed with shells, at the depth of 22½ fathoms.

We were in lat. 43° 20′ S.; long. 145° 10′ E.

The Esperance was apprised of our having cast anchor by a signal from the main-mast, and did the same at the distance of about 1,000 toises from us.

The slightest agitation produced a great degree of phosphorescence in the sea, during the whole night.

Very violent squalls, accompanied with rain, obliged us to pay out our cable, and unbend our top-gallant gear.

18th. The darkness of the sky kept us impatiently awaiting the moment when we could enjoy the beautiful prospect of the immense bay which forms the entrance of Strait Dentrecasteaux. At length the horizon cleared up. Whereever the eye could reach the coast was indented with spacious bights in the land, where navigators, driven by stress of weather, might fly for shelter with security. We surveyed with astonishment the immense extent of these harbours, which might easily contain the combined fleet of all the maritime powers of Europe. The right foreland of the strait bore S. 43° W.

As the wind abated about 11 o'clock in the forenoon, we availed ourselves of this opportunity to fit out the pinnace. The engineer was dispatched in order to examine whether an opening seen N. 30° E. afforded a passage for our vessels.

The ebb-tide drifted us from eight in the evening till two in the morning at the rate of half a knot every hour to N.W.N.

The stiffness of the breeze preventing us from sending any of our boats to the shore, we were obliged to remain on board.

19th. On the following day we were landed at the distance of 2,500 toises S.W. on an island which bounds this channel throughout its whole length. A boat belonging to the Esperance had passed the night at the same place, and taken a great quantity of fish.

It was a great gratification to me to traverse this country, where I found a large number of new plants, the most numerous of which belonged to the genus of melaleuca, aster, epacris, &c.

The shore of the channel afforded us a very easy path through the bushes which are here but thinly scattered. We afterwards climbed up some steep ascents which rise to about 25 toises perpendicular height above the level of the sea. We here observed a quantity of sea-salt deposited by the waves in the cavities of the hard freestone which forms the basis of these hills.

We had scarcely proceeded a thousand toises, when the remains of a hut and heaps of sea-shells shewed us that this island was inhabited.

We saw here for the first time the partridge of the Cape of Van Diemen. We sprung a very large covey of them, which lighted at a great distance from us,

Late in the evening we met Citizen Riche, who had passed the night with the fishermen. We gladly accepted his offer to share the fruits of his fishery with us, and he shewed us a small spring, where we had the pleasure of refreshing ourselves with excellent water over a meal of very fine fish and muscles, which we broiled upon the coals after the manner of the New Hollanders. After such a repast we had little occasion for the provisions we had brought with us from the ship.

We were informed that the principal officers of the Recherche had agitated the question among themselves, whether the gentlemen engaged in researches of natural history had any right to the fresh provisions distributed on board, whilst they were employed upon shore in making the collections which the object of their appointment required. Care was taken that none of their number should be admitted to these discussions; and as they had no one to support their right, the question was soon decided against them, contrary to every idea of justice. I must add, that though the persons who had the charge of providing for our table were frequently changed, they all adhered with the utmost punctuality to the dictates of this inequitable decree.

It was already night when our boat came to fetch us. Riche was obliged to avail himself of the opportunity; otherwise he would have been under the necessity of remaining on shore. He was, however, compelled to stay for the night on board of the Recherche, although it was of great consequence to him to return to the Esperance, as the preparation of the specimens which he had collected, required to be immediately attended to.

20th. A small island, situated S. 42° W. about 2,500 toises from our anchoring station, had been denominated Partridge Island by some of our crew who discovered it. Citizen Riche and myself spent the following day upon the island; but instead of partridges we found a great number of quails there. Whether those who had first visited it had taken the one fowl for the other, or whether the partridges had since left the island, I must leave undecided.

This small island is upwards of 100 toises in length, and situated in 43° 23′ 30″ S. lat. The new species of parsley, which I had denominated apium prostratum, grew in abundance upon the shore, almost as far as high water mark. We took a great quantity of it on board with us.

Many species of the casuarina grew here, and seemed to thrive very well notwithstanding the humidity of the soil. Amongst the plants which I saw for the first time was a remarkable species of the limodorum, of which I had a drawing taken; I also collected various kinds of ferns, and a beautiful species of the glycine, remarkable for its scarlet flower.

No fresh water is found upon this island; though several forsaken huts shewed that it had been frequented by the savages.

Two of the officers of our vessel, Cretin and Dauribeau, went about six o'clock in the morning to survey the coast to the eastward of our station, where they found several bays extending from N.W. to S.E. They observed several creeks, which formed as many harbours; but a strong contrary wind prevented them from examining them farther into the land. Seeing several fires at a small distance from the shore, they determined to land; when as soon as they had entered the woods, they found four savages employed in laying fuel upon three small fires, about which they were sitting. The savages immediately fled, notwithstanding all the signs of amity which they made them, leaving their crabs and shell-fish broiling upon coals. Near this place they saw other fires and huts.

It appears that this spot is much frequented, as fourteen fire-places were discovered.

One of these savages, who was very tall and muscular, having left behind him a small basket filled with pieces of flint, was bold enough to come quite near to Cretin in order to fetch it, with a look of assurance with which his bodily strength seemed to inspire him. Some of the savages were stark naked; the rest had the skin of a kangarou wrapped about their shoulders. They were of a blackish colour, with long beards and curled hair.

The utensils which they left behind them consisted of about thirty baskets made of rushes, some of which were filled with shell-fish and lobsters, others with pieces of flint and fragments of the bark of a tree as soft as the best tinder. These savages, undoubtedly, procure themselves fire by striking two pieces of flint together, in which they differ from the other inhabitants of the South Sea islands, and even from those of the more easterly part of New Holland; whence there is ground to believe that they are descended from a different origin.

They likewise left behind them several kangarou skins and drinking vessels.

The officers forbade the sailors to take away any of the utensils of the savages: they, however, selected two baskets, a kangarou skin, and a drinking vessel of fucus, to carry to the Commander. The savages had no reason to regret the loss of these utensils, as they left, in place of them, several knives and handkerchiefs, with some biscuit, cheese, and an earthen pot, perhaps too brittle, but certainly a very good substitute for that which had cost them so little labour to manufacture.

The savages, though they took very few of their utensils with them, dropped some of them from time to time on their flight. Whether they might do this in order to be able to run the faster, or whether it was with a design to amuse the Europeans who followed them, I cannot tell.

A boat belonging to the Esperance had been to examine a creek situated to the eastward, at the distance of about 5,000 toises. They had met with one of the natives, who, notwithstanding all the signs of amity they made him, would not let them come within two hundred paces distance of him. A fine rivulet discharges itself into the sea near the farthest extremity of the creek. The situation of this creek, opposite to an island which shelters it from the surges, renders it an excellent place of shelter for vessels that stand in need of any repairs.

The other creeks which they examined afforded in general very good anchorage.

They discovered a bay that extended so far to the north-east, that they could not get within view of its extremity. Possibly some of these bights in the land may be parts of channels which communicate with the sea on the opposite side.

The preparation of the specimens which I had collected on the preceding days, employed my whole leisure on the 21st.

The gardener went with six other persons in the long boat, with the view of landing at the island which I had examined on the preceding day. After having in vain contended with violent and contrary winds, they left the boat adrift, thinking it would run into a creek under shelter of a small island, situated at the entrance of the channel which they had before endeavoured to reach. But this step was very near proving their ruin: their sail fell into the sea, and the boat, being suddenly stopped in its course, soon began to be filled with water by the violence of the surge. At length they arrived, overcome with fatigue, under the shelter of the island, where the calm that prevailed afforded them a pleasing respite from their toils and dangers. The Commander, anxious about their fate, sent a boat in the afternoon in quest of them, as he knew that whilst the wind remained so unfavourable, the long boat could not return to the ship without assistance. Towards close of evening, we had the satisfaction of seeing them return on board. They told us that having proceeded along the coast in a S.S.E. direction, they found by some fires that the savages were near; that they had soon met with several of them, who were the same that had been seen the day before, but that they did not suffer them to approach them. They found some shell-fish broiling upon the fires which the savages had left with precipitation, and more than thirty kangarou skins which they found at a little distance, shewed them to be very expert in hunting.

It appeared that they had made use of the bread and water, which had been left for them on the preceding day; but the smell of the cheese had probably given them no inclination to taste it, as it was found in the same condition in which it had been deposited. They found at the same place one of the knives and handkerchiefs that had been left among the utensils of the natives.

Some shots that were fired at birds, probably terrified these savages; for when some of our men went to the same place two days afterwards, they saw none of them.

22d. The boats were sent to take in water at a creek that had lately been discovered to the eastward. I availed myself of the opportunity to visit this place, which was situated at the distance of about 5,000 toises from our anchoring station. It forms a harbour, about 150 toises in breadth and 500 in length, with sufficient bottom for large vessels to ride at anchor in it. A rivulet that discharges itself into it near its extremity, affords very good water, which, however, was not easily taken in by the boats, since, in order to have it perfectly pure, it was necessary to roll the barrels from the distance of more than 150 toises over the muddy bottom. Our men might have been spared this unhealthy labour, if pipes of leather or of sail-cloth, smeared over with tar, had been employed, by which the water might easily have been conveyed into the boats. The advantages of such a practice will particularly be apparent in cases where the impracticability of entering a rivulet with the boats obliges mariners to take in brackish water; whereas, by means of a pipe carried a few hundred yards higher up the stream, they might procure it without any admixture of sea-water, which renders it very unwholesome to drink.

The banks of this rivulet produced several new species of casuarina, one of which was remarkable for the club-like form of its fruit. I also observed a pretty tall shrub, which establishes a new genus of the cruciferous tribe.

The tracks of the kangarous were very numerous, terminating at the rivulet, where these animals frequently come to drink.

As the wind had been against us when we sailed for this watering place, we had a right to expect that it would be favourable to our return; but a calm supervened, and it lasted several hours before we reached the ships.

The pinnace returned after a voyage of four days, in which the whole extent of the strait had been surveyed. It is about 20,000 toises in length from S.W. to N.E. They had every where found a depth of at least six fathoms and an half, over a bottom of mud, and sometimes of fine sand. It is separated from Adventure-bay by a narrow slip of land, not more than 200 toises at its greatest breadth.

We now waited only for a favourable wind to follow the strait, in order to take an exact survey of it. The N. and N.W. breezes were contrary, and, besides, so slight, that we were obliged to remain the whole day at anchor.

During the night we saw several fires of the natives to S.E.

24th. On the following morning we weighed anchor, and plied to windward at the distance of about 500 toises from the land. We found every where a depth of water of at least 6½ fathoms, over a very good bottom.

Though the thermometer had never indicated more than 7° above the point of congelation, even in the coldest mornings, the snows had greatly increased upon the high mountains seen W.N.W.

Whilst the currents continued favourable we gained ground at every tack; but about six o'clock in the evening they became contrary; and we cast anchor in a bottom of grey sand at the depth of eight fathoms, very near to the coast, and to the northward of the station from whence we had sailed in the morning.

The natives kindled more than twenty fires upon the coast towards the south. Many families of them had probably come down to the coast upon hearing the news of our being in the bay.

25th. About seven in the morning the current was favourable, and we made several tacks in order to enter a narrower part of the channel, where we ranged very near to the west coast, steering N.E.N.

Having proceeded about 2,500 toises along this channel, we entered a second bay upwards of 5,000 toises in length, and bounded to the west by pretty high grounds; the eastern coast, which separates this strait from Adventure-bay, was less elevated.

About half an hour after one in the afternoon, we cast anchor at the distance of 500 toises from the shore; Cape Canelé bearing S. 33° E.

I went on shore to north-west, where I found the woods very full of thickets, and extremely damp, though no rain had fallen for several days. A new species of ptelea grew in great abundance amongst the shrubs with which this country was covered.

26th. We weighed anchor about seven in the morning, and found ourselves, at noon, in a third bay, where the great number of openings in the land left us for some time doubtful what course we should steer, in order to get out of it, which we a length accomplished, to north-west, by the most distant of the openings. The depth of water in this bay was not less than eleven fathoms about the middle, and at least six and a half at the distance of a hundred toises from the shore.

Having proceeded almost 10,000 toises to N.N.W. we anchored about half an hour after three in the afternoon, in a depth of fourteen fathoms and a half, with a muddy bottom. As it was probable that, in case the wind should become favourable, we might proceed on our course before night; none of us went on shore.

On the 27th, about eight o'clock in the morning, we weighed anchor. The current soon set against us, and obliged us to cast anchor at the depth of twelve fathoms and a half, in a bottom of sand mixed with mud. We were then in 43° 4′ S. lat. 145° 17′ E. long.

At the distance of two thousand five hundred toises to north-east, the farthest end of the strait through which we were to pass, was visible.

A fire at a small distance from the shore apprised us of the natives being near. We soon after observed one of them walking along the shore.

Two boats were sent out to transport some of our men to both shores of the straits. They discovered a number of the savages landing from a raft on the east shore. As timid as those we had seen before, they had hastened with all possible speed to the land, where they made their escape into the woods, leaving behind them several darts of a very clumsy construction.

I went on shore at the place where the savages had disappeared, and found several pieces of very beautiful hard granite, rounded by the water.

We found four rafts, made of the bark of trees, on the beach. These rafts are only fit for crossing the water when the sea is very tranquil; otherwise they would soon be broken asunder by the force of the waves. As the savages possess the art of hollowing the trunks of trees by means of fire, they might employ the same method to make themselves canoes; but the art of navigation has made as little progress amongst them as the rest.

Having arrived at the extremity of the strait, I found some fine crystals of feld-spath in several rocks of very hard sand stone.

On the tops of the hills I met with the plant described by Phillips, in his account of his voyage to Botany-bay, under the name of the yellow gum-tree. As it was already in seed, I had no opportunity of examining the characters requisite for determining its genus. To me it appears to belong to that of dracæna. The grains were contained in long ears, filled with a vast number of larvæ, which are afterwards metamorphosed into small phalenæ of the moth kind.

The gum-resin which flows from this plant is very astringent, and might, no doubt, be used with advantage in medicine. The gummy principle with which it abounds, renders it more apt to mix with the fluids of the human body, and ought to give it a preference before many other astringents that are employed.