Voyage in Search of La Pérouse/Volume 2/Chapter 14

CHAP. XIV.

10th May.

Early in the morning we set sail from New Caledonia, but were no sooner in the open sea than we were becalmed near a long range of rocks, which we perceived to eastward, and against which the sea broke in a tremendous manner; we however got clear of them, favoured by a light breeze from the south-east: sailed by them in a longitudinal direction on the 11th and 12th, and on the 13th descried beyond that chain to the west the island of Moulin, at about 17 miles distance, and afterwards the Huon Islands.

Next day our vessel was on the point of being dashed to pieces on the rocks with which these islands are surrounded, when at day-break we perceived the danger of our situation. We immediately tacked about and stood off from them, and discovered before the evening that these rocks were connected with those along which we had sailed the year before.

Soon after we steered for the island of Saint Croix, which, early on the morning of the 20th, we perceived to the north-west, at about twenty-two miles distance.

Next day, about four in the afternoon, being then three miles distant from the shore, we perceived two natives coming towards us in a canoe with an out-rigger. They kept at a great distance till five other canoes had joined them, when they came nearer to our ship. One only of these canoes carried three savages, the others contained no more than two. They addressed their conversation to us, and made signs for us to land upon their island, but none of them would venture on board our ship, notwithstanding repeated invitations to that effect. The boldest of them did not come nearer than about fifty yards. They were armed with bows and arrows, and their whole dress consisted of necklaces and bracelets ornamented with shells.

As night approached, our sailors worked the ship to stand on different tacks, when the savages left us and returned to the coast, but several hours afterwards, notwithstanding the darkness of the night, we were visited by another canoe, the savages in which certainly thought that we understood their language, for they spoke to us for a long time in a very low tone of voice, but, not receiving any answer, they at length returned to their island.

22d. At day-break we approached the coast, and soon perceived twelve canoes making towards us. They hastened alongside of our vessel, and the most of them were loaded with different kinds of fruit, amongst which I remarked the bread-fruit, but of a smaller size, and not so good in quality as what we had met with at the Friendly Islands; it was not, however, of the wild sort, for it only contained a very small quantity of seed.

We were not a little surprized to observe that those islanders set very little value on the iron which we offered them, though we could not doubt that they knew the use of it, for one of them had a piece of a joiner's chissel with a wooden handle, of the same kind as their stone hatchets; but when we showed them some pieces of red cloth, their admiration, expressed by the words youli, youli, gaves us hopes of succeeding better with these articles in bartering for their commodities than with our hardware. In fact they consented to sell us some of their arms, but probably fearing, lest we should turn them against themselves, they took the precaution not to part with any of their bows, and even to blunt the arrows which they sold us.

Soon after several of them gave us proofs of their dishonesty. With a view to cheat us of our articles in bartering, they at first offered a good equivalent, but insisted on having our goods delivered to them before hand, which they kept, refusing to give us any thing in return.

About eight o'clock in the morning, the General sent two boats to sound a creek, which we perceived at about a mile distance to the north-west. On a sudden we lost sight of them, and were under some apprehensions respecting them, when, about noon they appeared again at the mouth of the creek, which they had been to reconnoitre. Several musket-shot fired from these boats gave us to understand that they had been attacked by the savages. At the report, the canoes which surrounded us made off with great precipitation. Our boats were not long before they arrived, and informed us that the opening which we had taken for a bay, was the extremity of a channel, which separates the island of St. Croix from that of New Jersey. This channel extends in length N.E. ¼ E. being at the utmost not three miles long, and its greatest breadth does not exceed one mile. It was sounded with great accuracy, and a line of sixty-seven yards did not find the bottom in any part of at, not even within an hundred yards of the shore.

A great number of canoes had followed our boats, whilst large parties of savages on the shore endeavoured to entice our people to them, by shewing their cocoa-nuts, bananas, and several other fruits; at length some of them swam off with those productions of their island in exchange for such pieces of cloth of different colours as were intended for them.

Our boats on their return, at the entrance into the channel, and near a small village on the coast of New Jersey, were just leaving these savages, when one of them was seen to stand up in the middle of his canoe, and prepare to shoot an arrow at a man belonging to the boat of the Esperance. Every one seized his arms, but nevertheless the islander recommenced his signs of hostility, whereupon one of our men presented his musket, but the savage, without being terrified with this menace, bent his bow very deliberately and let fly an arrow, which struck one of the rowers on the forehead, although at the distance of about eighty yards. This attack was instantly returned by the discharge of a musket and blunderbuss, the latter of which having sent a shower of bullets into the canoe, from which the arrow had been discharged, the three islanders who were in it immediately jumped overboard. Soon after they returned to their canoe and paddled hastily towards the shore, but a ball at length reaching the aggressor, all three again jumped into the water, leaving their canoe, with their bows and arrows, which fell into the hands of our boat's crew.

All these canoes have out-riggers, and are constructed as represented in Plate XLVI. Fig. 3. Their bows are placed upon the platform, situated between the canoe and the out-rigger, and formed of close wicker work. The body of the canoes is in general fifteen feet long and six in width. It is of a single piece cut out of the trunk of a tree, very light, and almost as soft as the wood of the mapou. There is through the whole length an excavation of five inches wide. Here the rowers sit with their legs one before the other, and up to the calf in the hollow. They are seated on the upper part, which is smooth. At each of the extremities, which are formed like a heart, we observed two T's, the one above the other, cut out, but not very deep, and sometimes in relievo. The lower part of the canoe is very well formed for moving through the water. The out-rigger is always on the left of the rowers.

These islanders are accustomed to chew betel. They keep the leaves of it with areca-nuts, in small bags made of matting, or of the outer covering of the cocoa-nuts. The lime which they mix with it is carried in bamboo canes, or in calebashes.

These people are, in general, of a deep olive colour, and the expression of their countenances indicates an intimate connection between them and the generality of the inhabitants of the Moluccas; though we remarked some who had a very black skin, thick lips, and large flat noses, and appeared to be of a very different race; but all these had woolly hair and very large foreheads. They are in general of a good stature, but their legs and thighs are rather small, probably owing, in a great measure, to their inactivity, and the length of time which they are confined in their canoes.

Most of them had their noses and ears bored, and wore in them rings made of tortoise-shell.

Almost all were tatooed, particularly on the back.

I remarked with surprise that the fashion of wearing their hair white was very general among these savages, and formed a striking contrast with the colour of their skin. Without doubt, those petits maîtres used lime for that purpose; in the same manner as I had observed amongst the inhabitants of the Friendly Islands. They are in the habit of pulling up their hair by the roots. Their notions of modesty have not taught these people the use of clothes. They generally have their bellies tied with a cord, which goes two or three times round them. Their bracelets are formed of matted work, and ornamented with shells that have been worn; these are fixed to different parts of the arm, and even above the elbow.

The sailor, who had been wounded in the head by the arrow, did not feel much pain from it; he might have had it dressed immediately by the surgeon of the Recherche, but he chose rather to wait till we should get on board the Esperance. No one would, at that time, have supposed that so slight a wound would one day prove mortal.

As soon as the boats were hoisted on board the vessels we stood to the south-west, a quarter west, coasting the island of St. Croix, at the distance of about three quarters of a mile, and observed many of the savages call to, and invite us to land. Several amongst them launched their canoes to come to us, but we sailed too fast for them to overtake us.

We discovered some mountains, the highest of which were at least three hundred yards perpendicular; they were all covered with large trees, between which we perceived here and there very white spots of ground, which appeared to be laid out in beds.

From thence, after having sailed along the coast about nine miles, we found ourselves opposite to a large bay, which has, without doubt, a good bottom, but it is exposed to the south-east wind, which blew at that time.

We soon after perceived at a distance, to the south, several canoes making towards the island of St. Croix; others were seen at a still greater distance, apparently employed in fishing in shallow water; at the same time we descried to the south another shoal very near us, and which extended far to the westward.

We had just discovered Volcano Island, when a great number of canoes left Gracious Bay, and made towards us, and as we had very little wind, they had sufficient time to come up with us. We already counted seventy-four, which had stopped at the distance of eight or nine hundred yards from the vessel, when the clouds, which had gathered on the mountains, caused the savages, by whom these perilous vessels were manned, to be apprehensive for their safety if they remained longer at sea. They immediately paddled towards the shore, but before they had reached it a violent squall, accompanied with a heavy shower of rain, very much impeded their progress.

We stood off and on all night. The General proposed to anchor in Gracious Bay the next day. Several fires were kindled on the coast, to which we were near enough to distinguish the voices of the inhabitants, who seemed to be calling to us. We fired several muskets, intending to give them an agreeable surprize, and immediately cries of admiration were heard from different parts of the coast, but the most profound silence succeeded to these demonstrations of joy, although several other shot were fired.

23d. We did not perceive during the night, upon Volcano Island, any indications that it still contained subterraneous fire. This small island cannot contain a sufficient quantity of combustible matter to supply incessantly the volcanic fire, which Captain Carteret had observed there twenty-six years ago.

The south-east wind continued all that day, and even on the next (24th), prevented us from entering the Bay, near which a great number of cottages were built under the shade of the cocoa-trees, that were planted along the beach.

The natives soon made their appearance on the shore, when the General sent out two boats, following them with our vessels, so as to cover them in case of an attack from the natives. The surf was too great to admit of our landing, nevertheless several of the natives swam to us, bringing cocoa nuts in exchange for pieces of red cloth, which they preferred before every other article we offered them. Some came in their canoes, and all of them appeared very honest in bargaining with us, which was perhaps owing to their having heard what had passed between us and the inhabitants of the east side of the island. They, however, offered us only the worst things they had; most of the cocoa nuts they brought were growing seedy. It was not till after some time that they would sell us some bows and arrows, but fearing lest we should turn these arms against themselves, they took the precaution to carry the bows to one boat and the arrows to another. The latter were not pointed. We observed, that by means of a reddish gum, a small piece of bone or tortoise-shell, about half an inch long and well sharpened, was fixed to the end of them; others were pointed with the same sort of materials from ten to twelve inches long; but many were armed with the bone which is found next the tail in that species of ray called raia pastinaca.

We observed several hogs on shore, which they would not bring to us at any price, but promised to sell them if we would come ashore.

I remarked in their possession a necklace of glass beads, some green and others red, which appeared to me to be of English manufacture, and which they agreed to exchange.

We bought from these inhabitants a piece of cloth, which gave us no very favourable idea of their industry: it was composed of coarse bark of trees, and very indifferently joined together.

One of them wore, suspended upon his breast, a small flat circular piece of alabaster, which he parted with to satisfy us.

This interview had lasted nearly two hours, when, at a signal from one of their chiefs, all the savages left us; but, when they saw our boats preparing to leave the shore, the women came close to the water's edge to endeavour to persuade us to land: we, however, continued steady to our purpose, in a short time got on board the vessels, and soon after set sail for the Islands of Arsacides.

On the 26th, about ten A.M. we perceived the Islands of Deliverance to the westward. At noon we discovered the southernmost of them, between W. 13° S. and W. 19° S. distant about twelve miles, and the other bearing W. 27° S. We found, by observation, that our vessel was in 10° 48′ S. lat. and 160° 18′ E. long. Almost the whole circumference of these two small islands is very rugged, but they do not lie very high. We perceived inhabitants upon them, and large plantations of cocoa trees.

We then crowded sail for the Arsacides, the lofty mountains of which we saw to the west-south-west.

27th. We coasted along it this day. About ten A.M. we had just passed a shoal near two miles in breadth, when, through the negligence of the watch, the ship went over another shoal, where, however, there was fortunately sufficient water to prevent her receiving any injury.

At noon we were in lat. 10° 54′ south, and long. 159° 41′ east, when the land of the Arsacides bore from east 21° north, to west 23° north: we were then about three miles to the south of the nearest shore. These coasts were indented, having small hills projecting into the sea, forming a number of little bays, which afforded shelter from the east wind. Most of these small capes are each terminated by a pyramidal rock of considerable height, crowned with a tuft of very green bushes. Farther in the interior of the country we saw the same kind of small hills standing on mountains of a moderate height, which exhibited a very picturesque appearance.

It was generally at the extremity of the small creeks that the inhabitants fixed their residence. Many of them had come upon the beach to enjoy the novel spectacle which our vessels presented to them. Their cottages were built under the shade of numerous plantations of cocoa trees.

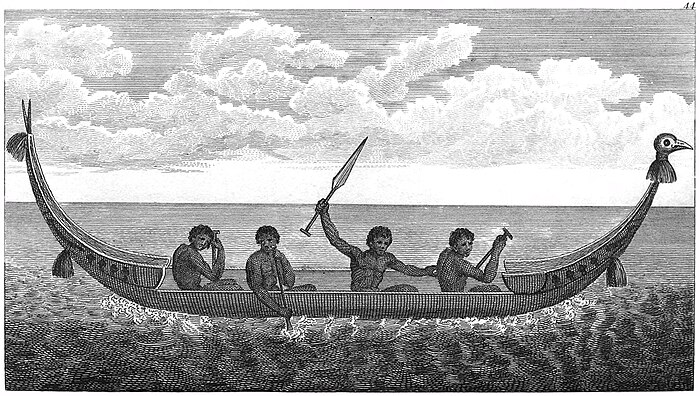

We had not yet seen any canoes on that coast, when, about four in the afternoon, one came towards us. We were much astonished that the islanders who were in it durst venture out on a sea greatly agitated in so frail a vessel, the width of which was not any where more than two feet, and they sat in the deepest part in order to preserve a proper equilibrium. (See Plate XLIV.)

After having approached to about two hundred and fifty yards of our frigate, they addressed a few words to us in a very elevated tone of voice, pointing to their island, and inviting us to go on shore. They then came still nearer, but a violent gust of wind compelled them to return to the shore.

These islanders had not more clothing than the inhabitants of the island of St. Croix, to whom they bear great resemblance.

28th. This morning at day-break we perceived that the current had driven us 18′ east during the night. Our surprise at this was the greater, as the easterly wind, which prevailed at this time, should have counteracted the force of the currents. Can the tides occasion this singular direction of the currents in these latitudes?

About ten in the morning four canoes came off the shore and advanced to within about four hundred yards of our ship, but we could not wait for their nearer approach, as we were obliged to continue our course to double a cape which would have interrupted some nautical observations we intended to make.

At noon we were in 10° 33′ S. lat. and 158° 57′ E. long. and we saw the sea breaking with great violence against Cape Philip, which is a very rugged point. We doubled it about four P.M. and soon after perceived a large bay, the shores of which appeared to be very populous. We saw several sheds under which the inhabitants had put their canoes to shelter them from the weather, and observed cottages in every part even to the summits of the highest mountains.

Soon after the savages launched five canoes, and sailed towards us. They all kept within call except one man, who, mounted in a catimarron canoe, came much nearer the stern of our vessel, to receive some pieces of red cloth which we had thrown into the sea. His behaviour indicated the greatest mistrust. He kept his eyes fixed on us, none of our motions ecscaped him, and at the same time he had the dexterity to catch every article that we threw him. The appearance of this native, seated upon a few planks, beat about by the waves, amused us for some seconds. Our musician wanted to entertain those islanders with some tunes on the violin, but just as he was tuning his instrument, they went off towards the Esperance.

Soon after five other canoes came alongside our vessel, testifying the greatest confidence in us. The natives by which they were manned were certainly acquainted with the use of iron, for they expressed great joy upon receiving some nails which we offered them. We could not learn whether these people are used to barter their commodities: at least we were not able to obtain any thing from them by this mode of traffic, although they had javelins, tomahawks, bows and arrows. They were, however, very willing to accept of any thing that we offered them by way of present, and made us very obliging proposals if we would land upon their coasts; whilst, with their natural gaiety of manner, they frequently repeated the word sousou (the bosom), accompanying their discourse with very significant gestures, which produced great merriment among our sailors.

At sun-set the savages returned on shore and kindled three large fires.

29th. The currents had carried us during the night into a large channel which runs along this easterly island of the Arsacides, formerly called the Island of St. Christopher, and belonging to the archipelago of Solomon, discovered by Mendana. It now bore north, and soon after we descried the Isle des Contrariétés, which about noon bore E. 14° N. to E. 30° N. at a distance of 5,180 toises, we being in 9° 53′ S. lat. 159° 8′ E. long. This small island is rather mountainous and very woody.

We soon coasted along the small islands called the Three Sisters, after which we plied to windward, in order to get to the southward, so as to pass the strait which separates the island called by Mendana Guadal-canal from that of St. Christopher.

About eight in the evening the Esperance came near enough to us to acquaint us, by the speaking-trumpet, of a piece of treachery which had been practised upon her crew by the islanders. She had been surrounded, during the preceding night, by a great number of canoes, from which only two of the natives came on board. These savages commended, in very high terms, the fruits of their island, and promised to give a great quantity of them to our men, if they would come on shore: at length they departed about midnight; but amongst the number of canoes which remained near the Esperance, one was observed much larger than the rest, which, about break of day, rowed several times round the vessel, and suddenly stopping, at least twelve arrows were discharged from it, one of which wounded one of the crew (Desert) in the arm; the greater part of the rest, fortunately, sticking in the sides of the ship. After making this perfidious attack, they immediately fled with precipitation, and were already at a considerable distance before a musket was fired at them: none of them were wounded; but a rocket, which was discharged with a very good aim, and burst quite close to the canoe, terrified them exceedingly.

The other canoes had likewise fled at first, but they soon returned to the vessel.

This act of treachery, and the perfidious conduct of the same savages to Captain Surville, gave us reason to believe that they had been actuated by the same motives, when they used their utmost endeavours to persuade us to land upon their island.

30th. Being scarcely able to govern our vessel, on account of the slightness of the breeze, which blew by intervals from N.W. and W.N.W., we were very perceptibly carried by the currents towards the Isle des Contrariétés. As the sky was very clear, we had a good view of the island, of which the engraving published by Surville

Canoe of the Arsacides affords a pretty exact representation. We were at the distance of 1,500 toises, when a canoe rowed from the shore, and came alongside of our vessel. It was manned by four of the natives, who were very thankful for the presents of stuffs and hardware which we made them, and immediately gave us in return some cocoa-nuts, which, like most of the natives of the South Seas, they call niou.

They appeared highly pleased with the nails which we gave them; and continually begged for more, frequently repeating the word maté (death), and endeavouring to intimate to us by their gestures, that they intended to employ them against their enemies. Eight other canoes soon joined the first, and approached our vessel without shewing any signs of fear. We admired the elegant form of their canoes, which were exactly similar to those we had seen the preceding days at the easterly part of the Arsacides. (See Plate XLIV). They were about twenty-one feet in length, two in breadth, and fifteen inches in depth. The bottom consisted of a single piece cut from the trunk of a tree, and the sides were formed of a plank, the whole length of the boat, supported by beams fixed at equal distances into the bottom: at both ends other planks were attached to the first. These were ornamented on the outside with figures of birds, fishes, &c., rudely carved. The greater part of the canoes were terminated in front with the head of a bird, under which was seen a large bunch of fringe, coloured with a red dye, which appeared to me to have been made of the leaves of the vacoua. The other extremity of the boat was likewise ornamented with red fringe, and here we frequently observed, in the inner side, the carving of a dog projecting from the vessel, which led me to suppose that the savages possess this animal. I was surprised to observe that they had given it nearly the form of a blood-hound; though it is probable they do not possess that species, but that the carving was nothing more than an imperfect representation of the dog usually met with in the South Sea Islands.

The savages were obliged to remain constantly at the bottom of their canoes, in order to prevent their being overset by the waves, and, what rendered their situation still more incommodious, they had to sit in the water which was thrown in by the surge. They, however, took care to bale it out from time to time.

Amongst the commodities which were obtained from them, was a long fishing line attached to the extremity of a large rod, which appeared to me somewhat remarkable, as the greater part of the savages we had hitherto seen, were in the practice of holding their fishing lines in their hands. The hook was made of tortoise-shell.

Some of these natives wore as ornaments, bracelets made of various kinds of shells; others had them of the rind of the cocoa nut, bespangled throughout their whole circumference with a great number of coloured seeds.

It does not appear that they chew betel; at least I never perceived any signs of their doing it.

After these boats had remained several hours about our vessel, one of their chiefs gave them the signal for departing, upon which they immediately rowed towards the coast with great speed. One of the boats, however remained a few moments, to receive some pieces of red cloth which we were about to present to the natives at the instant when the signal was given; but as soon as these islanders saw that their companions had left them behind, they plied their oars with all the speed they were able, in order to overtake them. We were amazed to see their canoe skim the waves with such rapidity, that it must have run at the rate of at least 7,500 toises an hour.

June 1st. Early in the morning we began to range along the southern coast of Guadal-canal, which descends with a very gentle declivity to the sea, and observed in the interior part of the island a long chain of very high mountains, running in the same direction. We soon distinguished the Mount Lama of Shortland. The coast was bordered with cocoa trees, under the shade of which we observed a great number of huts. The low grounds rendered a large extent of this coast inaccessible to our vessels, and we were much incommoded by the currents which carried us to eastward. This unexpected direction of the currents surprised us the more, as the winds that had prevailed during our stay in these parts might have been expected to direct their course to the westward.

On the morning of the 4th, we doubled Cape Hunter, discovered by Shortland. About ten o'clock we passed quite close to a small island connected by some reefs to the coast, where we saw several groups of the savages seated under the shade of fine plantations of cocoas, and bananas, which give this island a very picturesque appearance. A great number of canoes lay upon the beach, and we expected that the natives would put to sea with some of them to come to our vessels; but their indifference astonished us: not one of them moved from his place, nor even rose from his sitting posture in order to have a better view of our ships.

This small island is situated in 19° 31′ S. lat. 157° 19′ E. long.

We soon came in sight of the westernmost point of Guadal-canal.

On the 7th, about noon, we descried the largest of Hammond's islands, N. 4° W. to E. 6° N. at the distance of 5,130 toises, we being in 8° 49′ S. lat. 155° 9′ E. long. We now left this archipelago, and made sail for the northern coast of Louisiade.

The survey which we had taken of the Arsacides, left us no room to doubt of their being the archipelago of Solomon, discovered by Mendana; as had been supposed upon the same grounds by Citizen Fleurieu, in his excellent work upon the discoveries of the French.

On the 9th, the Esperance informed us of the death of an unfortunate man of her crew (Mahol), who had been wounded in the forehead, seventeen days before, by an arrow from one of the savages of the island Sainte Croix. The wound, however, had cicatrized very well, and, for fourteen days, the man had felt no troublesome symptom whatever; when he was suddenly attacked with a violent tetanas, under which he expired in three days time.

Many of our company supposed that the arrow with which he was wounded had been poisoned; but this conjecture appears to me improbable, as the wound cicatrized, and the man remained fourteen days in good health. Besides, we found that the arrows, left in the canoe by the savages, and afterwards taken possession of by our sailors, were not poisoned; for several birds that we pricked with them experienced no troublesome consequences from the puncture: but it is a common occurrence in hot climates, that the slightest puncture is followed by a general spasmodic affection, which almost always terminates fatally.

On the 12th, about ten in the morning, we descried the coasts of Louisiade, and at first mistook the most easterly extremity for Cape Deliverance, but soon discovered that to be 25′ farther north.

We were astonished to find that the rapidity of the currents had been so great as to carry us 44′ to the northward in the space of twenty-four hours. The observations made on board the Esperance gave the same result.

We now steered west, coasting along pretty high lands, from which, however, we were obliged to keep at a considerable distance, on account of the great number of shoals which extended very far into the sea, and rendered our navigation extremely dangerous.

On the 14th, at day-break, we found ourselves surrounded with rocks and shoals, amongst which we had been carried during the night by the currents from W.N.W. In vain we plied to windward with a very good south-east breeze, with a view of extricating ourselves from this dangerous situation; the currents always prevented us from getting beyond a small island situated to the north-east, at the distance of 2,500 toises, near which there appeared to be a passage into the open sea. We were then in 10° 58′ S. lat. 151° 18′ E. long. Our room for beating became more confined, and our situation the more hazardous, in proportion as we were carried farther to the westward; besides, we found no bottom, so that we were at length obliged to resolve venturing among the shoals to the N.W. in hopes of finding there a passage for our vessels; but this resolution was not taken till late in the evening. It was already night when we found ourselves becalmed in a narrow channel, and at the mercy of a rapid current, which might every moment prove our destruction, by driving us upon the rocks with which we were surrounded. However, at break of day we had the satisfaction of finding ourselves in the open sea, extricated from all our dangers. Our situation had undoubtedly been a very hazardous one; but since we had already traversed seas full of shoals, we were become so accustomed to danger, that myself, as well as several others of our company, went to bed at our usual hour, and slept as soundly as if we had been in a state of the most perfect security.

17th. The coasts, along which we had hitherto ranged to the northward of the islands, were intercepted by a great number of channels. We had seen many habitations in this numerous collection of islands, but not one of the natives. On the 20th, being in latitude 10° 8′ S. long. 149° 37′ east, and sailing at a small distance northward of a cluster of small islands, we observed fifteen of the natives coming out of their huts. Three of them immediately entered a canoe, and made towards us, but we sailed so fast, that they were not able to come up with our vessels.

Another canoe soon appeared near the westernmoft island of the group; it was much larger than the former, and carried an almost square sail, which being immediately loosed, it soon came very near to us, but all our endeavours to persuade the men to come alongside of our vessel were in vain. They afterwards made towards the Esperance, and having approached within a small distance of her, drew in their sail, and would not come nearer; our vessels were then lying to. Citizen Legrand, being very desirous of an interview with the natives, threw himself into the sea, and soon swam up to the canoe. We were informed in the evening that this officer had not seen any arms amongst them; and, that though they were twelve in number, they had shewed some signs of fear when they saw him approach them.

It appears that they are unacquainted with the use of iron, as they seemed to set little value upon that which he presented to them.

These islanders were of a black colour, not very deep, and stark naked. Their woolly hair was ornamented with tufts of feathers, and they wore cords bound several times round the circumference of their bodies, undoubtedly intended to afford a support to the muscles of the belly. Many of them wore bracelets made of the rind of the cocoa tree.

We admired their dexterity in steering near the wind when they returned to the shore.

On the morning of the 18th, two canoes with out-riggers and sails, each manned by twelve savages, sailed swiftly round our vessel, watching us with great attention, but at a considerable distance. They afterwards kept for a long time to windward of us. We were then in 9° 53′ S. lat. 149° 10′ E. long. There was every appearance of great population on the southern coast, and especially towards the farther end of a large bay that extends to S.S.W. We soon perceived several canoes rowing towards us, each manned by ten or eleven natives, who kept at the distance of about a hundred yards from our vessel, till some pieces of cloth, which we threw into the sea for them, induced them to approach nearer. They appeared much surprized at seeing a young black on board of our vessel, whom we had brought with us from Amboyna. They did not understand him when he addressed them in the Malay language. These savages had all woolly hair and olive-coloured skins; I observed, however, one amongst them who was as black as the negroes of Mozambique, and resembled them also in other particulars. His lower lip, as is the case with them, projected considerably beyond the upper. All these islanders used betel; and they were all stark naked. They wore bracelets ornamented with shells. Many of them had a small piece of bone passed through the partition between the nostrils; others wore a string of shells like a scarf over their shoulders.

They presented to us roots baked in the ashes, and carefully peeled. We observed no other weapons amongst them than short javelins, pointed only at one end.

Their huts were supported six or eight feet above the ground upon stakes, like those of the Papous.

These savages wished us to land upon their island, but observing that we receded farther from it, in consequence of the currents which carried us to the westward, they left us and returned to their coasts.

Two of the canoes were still quite close to the Esperance at half after three o'clock, when we observed three muskets fired from that vessel, upon which the savages fled, rowing with all their might. We soon learnt that the men in one of the canoes had thrown stones at the crew of the ship without the least provocation having been given. None of the sailors, however, had been wounded by this act of treachery; and the muskets had been fired only to terrify them.

Soon after two boats were dispached in order to sound several creeks along the coast; where we hoped to find good anchorage. We found ourselves disappointed; as it was necessary to approach within a hundred yards of the coast, before the bottom could be reached with a line of seventy yards; and at the distance of two hundred yards we could not strike the ground with a line of less than a hundred and sixteen.

Notwithstanding the fright which the muskets fired at their companions might have given them, some of the natives came alongside of our vessel from the very place to which the others had made their escape. They shewed themselves very fraudulent in their dealings with us, bargaining at any price for the commodities which we had to barter with them, and as soon as they had got them in their possession, refusing to give us any thing in return. One of them, however, consented to give up to us a flute and a necklace, which are represented in Plate XXXVIII. Fig. 26 and 27.

I observed one of the natives who wore, suspended from his neck by a thin cord, a part of a human bone, cut from about the middle of the cubitus. Whether this might be a trophy of some victory gained over an enemy, and those natives belong to the class of the cannibals, I cannot tell.

Many of them had their faces smeared over with the powder of charcoal.

They generally cover their natural parts with large leaves of vacoua, passing between their thighs, and fastened to the girdle before and behind by a very tight ligature.

They had with them some pretty large fishing nets, to the lower end of which they had fastened various sorts of shells; some of these shells they carried in small cylindrical baskets, furnished in the inside with cords seemingly intended to prevent their breaking.

They used combs with three diverging teeth, some made of bamboo, others of tortoise-shell.

The savages left us at the close of the evening, and we plied to windward during the whole night.

We had scarcely advanced more than 10,000 toises to the N.E. since the preceding evening, when we found ourselves surrounded with low islands connected by shoals, amongst which we were obliged to beat even during the night. We several times passed over flats, which we could distinguish by the dim light of the moon, and often found ourselves in less than ten fathoms water.

A calm coming on about midnight, left us at the mercy of the current, which carried us towards the coast where the savages had lighted several fires.

At break of day we perceived the Esperance at a great distance from us, and much nearer to the land than our vessel, so that she was obliged to be towed by the boats.

The savages soon came in great numbers alongside of our vessel, but were not to be prevailed upon to come on board. An old man, who had already left his canoe in order to comply with our invitation, was prevented by the rest, who eagerly pulled him back to them, as if they imagined him to be about to expose himself to some great danger.

We thought that we recognized amongst these islanders some of those whom we had seen on the two preceding days. They were very curious to know the names of the things we gave them; but what surprised us very much was, that they enquired with the terms poe nama, which very much resemble the Malayan words apa nama, signifying "what is the name of this?" They, however, understood none of the men in our ships, who addressed them in the Malay language.

These savages brought with them a sort of pudding, which we found to consist partly of roots and the flesh of lobsters. They offered us some of it, and those of us who ate of it, found it very well tasted.

Most of these islanders made use of a human cubitus, scooped out at the extremity, for drawing the pieces of chalk which they mixed with their betel, from the bottom of a calabash.

They sold us an axe shaped like that represented in Plate XII. Fig. 9; it was made of serpentine stone, very well polished, and hafted with a single piece of wood. The edge of the axe was in the direction of the length of the handle, as in ours.

These islanders are very fond of perfumes; most of the things we got from them were scented. They had pieces of the bark of different aromatic trees, one of which seemed to me to belong to the species of laurel, known by the name of laurus culilabau, which is very common among the Molucca islands.

The calm still continued, and about one o'clock the Commander sent the barge to assist in towing the Esperance, as the crew might be supposed already much fatigued with their labour. At length, about half an hour after four a breeze sprung up from the south-east, which enabled her to get clear of the shoals. The barge soon returned to our vessel, when we were informed that the Esperance had been surrounded for a long time by a great number of the savages; that about noon they had pointed out to the crew two canoes rowing from two small islands to meet each other, and given them to understand that the islanders in the boats were going to fight a battle, and that these who came off conquerors intended to devour their enemies. During this recital, a ferocious expression of pleasure was visible in their countenances, as if they were to partake of this horrible banquet. After this communication, almost all those among our crew who had eaten of the pudding, which the savages brought them in the morning, were seized with retchings, from the apprehension that this food, which seemed to be so highly grateful to the islanders, was partly composed of human flesh.

The two canoes were soon near enough together to commence the engagement. The combatants were seen mounted upon a platform of wood, supported by the out-rigger and the canoe, from whence they threw stones with their slings, each of them wearing a buckler upon his left arm, with which he endeavoured to ward of the stones thrown by his adversary. They, however, separated after a fight of half a quarter of an hour, in which none of them appeared to have been dangerously wounded, and returned to the shore.

The captain of the Esperance sent to the Commander a tomahawk and a buckler which he had obtained from these savages.

The tomahawk was very broad, and flat at one of its extremities. The buckler was the first defensive weapon which we had observed among the savage nations we had hitherto visited. It was made of very hard wood, and of the form represented in Plate XII, Fig. 7 and 8. It was nearly three feet in length, a foot and a quarter in breadth, and upwards of half an inch in thickness. The outer side was slightly convex. About the middle of Fig. 8, which represents the inner side of the buckler, three small pieces of cane are visible, by which the islanders fix it to the left arm.

Though the natives had been in great numbers about the Esperance, they had attempted no act of hostility, except that one of them appeared to be preparing to throw a javelin at one of the crew who was upon the wale, but seeing himself observed, he desisted from his design, and the canoe in which he was rowed away from the vessel with precipitation.

On the following days we sailed by some very low small islands, beyond which we saw very high lands to the southward. The prodigious numbers of flats which we continually encountered, prevented us from ranging nearer to the coast.

On the 25th, being in 8° 7′ south latitude, 146° 39′ east longitude, we saw the high grounds of New Guinea extending from south-west to north-west. After having followed them in their direction to north-west, we arrived on the 27th at a deep gulph, about 40,000 toises in extent, and surrounded by very high mountains, the loftiest of which are on the north side, where they unite with that which forms the Cape of King William. The calm detained us here till the 29th, when we sailed for the straits of Dampier.

On the 30th, at break of day, we discovered to the N.W.W. a very high mountain furrowed near its summits by longitudinal excavations of a great depth. This was the Cape of King William. We afterwards observed the western coast of New Britain, for which we steered under full sail, in order to get before night to the northward of the straits of Dampier. The sun being in our face, the man at the mast-head could not perceive timely enough a flat over which we passed about eight in the morning, the surge running very high. After getting clear of this, we thought ourselves out of all danger; but about three quarters of an hour after, we found ourselves between two shoals very near to each other, which inclosed us in such a manner, that it was impossible to pass through with the south-south-east wind, which drove us farther and farther in. The Commander gave orders immediately to put about; but there was not time sufficient to perform this manœuvre, before our vessel drove towards the shoals to the northward, where we expected she would soon be wrecked, when Citizen Gicquel cried from the mast-head that he saw a passage between the rocks which, though very narrow, was yet wide enough for our vessel to sail through. We immediately steered for this passage, and were at length extricated from one of the most hazardous situations which we experienced during the whole course of our expedition. We were, however, not yet out of all danger, being still surrounded for some time by other shoals, which obliged us several times to change our direction; but we were at length fortunate enough to find a passage through the narrow straits by which they were separated from each other.

About noon we were already very far up the strait, our latitude being 5° 38′ south, longitude 146° 24′ east.

The coast of New Britain bore from east 37° south, to east 61° north, we being at the distance of 2,500 toises from the land.

The island on which Dampier discovered a volcano bore west 38° north, at the distance of 7,600 toises. This volcano was then extinguished; but we saw, at the distance of 5,130 toises, west 28° north, a small island of a conical form, which was not observed by Dampier to exhibit any signs of subterraneous fire. A thick smoke proceeded at intervals from the summit of the mountain; and about half an hour after three, a great quantity of burning substances were thrown out of the aperture of the volcano, which lighting upon the eastern declivity of the mountain, rolled down the sides till they fell into the sea, where they immediately produced an ebullition in the water, and raised it into vapours of a shining white colour. At the moment of the eruption, a thick smoke, tinged with different hues, but principally of a copper colour, was thrown out with such violence, as to ascend above the highest clouds.

We saw a great number of inhabitants along the coast of New Britain, and several huts raised upon stones, after the manner of the Papous.

We left the strait before close of evening.

We now ranged along the northern coast of New Britain, where we discovered several small islands, very mountainous, and hitherto unknown. The currents in this passage were scarcely perceptible, except under the meridian of Port Montague, where they carried us rapidly to the northward, which led us to suppose that we were opposite a channel that divides the lands of New Britain. We left this coast on the 9th July, after having been impeded in our survey of it by the winds from the south-east, and the frequent calms.

We had been obliged for a long time to live upon worm-eaten biscuit and salt-meat, which was already considerably tainted, in consequence of which, the scurvy had begun to make great ravages amongst us. The greater part of us found ourselves compelled to leave off the use of coffee, as it occasioned very troublesome spasmodic affections.

On the 11th we steered very near the Portland Islands.

In the afternoon of the 12th we espied the most easterly of the Admiralty Isles.

On the 18th, about sun-set, we discovered the Anchorites S.W. by W.

About seven o'clock in the evening of the 21st we lost our Commander Dentrecasteaux; he sunk under the violence of a cholic which had attacked him two days before. For some time he had experienced a few slight symptoms of the scurvy, but we were far from imagining ourselves threatened with so heavy a loss.

August 2d. we descried the Traitors Islands, and about noon we saw them at the distance of 20,000 toises, from S. 35° W. to S 42° W. we being in 6′ S. lat. 134° 3′ E. long.

On the 8th our baker died of the scurvy, his whole body having been previously affected with an emphysema, which had encreased with astonishing rapidity, in consequence of the heats of the Equator.

On the 11th we doubled the Cape of Good Hope of New Guinea, and on the 16th cast anchor at Waygiou.