A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Time

TIME (Lat. Tempus, Tactus; Ital. Tempo, Misura, Tatto; Fr. Mesure; Germ. Takt, Taktart, Taktordnung).

No musical term has been invested with a greater or more confusing variety of significations than the word Time; nor is this vagueness confined to the English language. In the Middle Ages, as we shall show, its meaning was very limited; and bore but a very slight relation to the extended signification accorded to it in modern Music. It is now used in two senses, between which there exists no connection whatever. For instance, an English Musician, meeting with two Compositions, one of which is headed, 'Tempo di Valza,' and the other, 'Tempo di Menuetto,' will naturally (and quite correctly) play the first in Waltz-Time'; that is to say, at the pace at which a Waltz is commonly danced; and the second, at the very much slower pace peculiar to the Minuet. But an Italian Musician will tell us that both are written in 'Tempo di tripla di semiminima'; and the English Professor will (quite correctly) translate this by the expression, 'Triple Time,' or '3-4 Time,' or 'Three Crotchet Time.' Here, then, are two Compositions, one of which is in 'Waltz-Time,' and the other in 'Minuet Time,' while both are in 'Triple Time'; the words 'Tempo' and 'Time' being indiscriminately used to indicate pace and rhythm. The difficulty might have been removed by the substitution of the term 'Movimento' for 'Tempo,' in all cases in which pace is concerned; but this word is very rarely used, though its French equivalent, 'Mouvement,' is not uncommon.

The word Tempo having already been treated, in its relation to speed, we have now only to consider its relation to rhythm.

In the Middle Ages, the words 'Tempus,' 'Tempo,' 'Time,' described the proportionate duration of the Breve and Semibreve only; the relations between the Large and the Long, and the Long and the Breve, being determined by the laws of Mode,[1] and those existing between the Semibreve and the Minim, by the rules of Prolation.[2] Of Time, as described by mediæval writers, there were two kinds—the Perfect and the Imperfect. In Perfect Time, the Breve was equal to three Semibreves. The Signature of this was a complete Circle. In Imperfect Time—denoted by a Semicircle—the Breve was equal to two Semibreves only. The complications resulting from the use of Perfect or Imperfect Time in combination with the different kinds of Mode and Prolation, are described in the article Notation, and deserve careful consideration, since they render possible, in antient Notation, the most abstruse combinations in use at the present day.

In modern Music, the word Time is applied to rhythmic combinations of all kinds, mostly indicated by fractions ( etc.) referring to the aliquot parts of a Semibreve—the norm by which the duration of all other notes is and always has been regulated. [See Time-Signature.]

Of these combinations, there are two distinct orders, classed under the heads of Common (or Duple) Time, in which the contents of the Bar[3]—as represented by the number of its Beats—are divisible by 2; and Triple Time, in which the number of beats can only be divided by 3. These two orders of Time—answering to the Imperfect and Perfect forms of the earlier system—are again subdivided into two lesser classes, called Simple and Compound. We shall treat of the Simple Times first, begging the reader to remember, that in every case the rhythmic value of the Bar is determined, not by the number of notes it contains, but by the number of its Beats. For it is evident that a Bar of what is generally called Common Time may just as well be made to contain two Minims, eight Quavers, or sixteen Semiquavers, as four Crotchets, though it can never be made to contain more or less than four Beats. It is only by the number of its Beats, therefore, that it can be accurately measured.

I. Simple Common Times (Ital. Tempi pari; Fr. Mesures à quatre ou à deux temps; Germ. Einfache gerade Takt). The forms of these now most commonly used, are—

1. The Time called 'Alla Breve,' which contains, in every Bar, four Beats, each represented by a Minim, or its value in other notes.

This species of Time, most frequently used in Ecclesiastical Music, has for its Signature a Semicircle, with a Bar drawn perpendicularly through it[4] ( ); and derives its name from the fact that four Minims make a Breve.

); and derives its name from the fact that four Minims make a Breve.

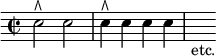

2. Four Crotchet Time (Ital. Tempo ordinario;[5] Fr. Mesure à quatre temps; Germ. Viervierteltakt) popularly called Common Time, par excellence.

![{ \time 4/4 \override Score.Clef #'stencil = ##f \clef bass

e4^\rtoe e e^^ e | e8^\rtoe e e[ e] e^^ e e[ e] | s_"etc." }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/r/oriai58k9e0541tavk2kis0to24bf53/oriai58k.png)

This kind of Time also contains four Beats in a Bar, each Beat being represented by a Crotchet—or its value, in other notes. Its Signature is an unbarred Semicircle ( ), or, less less commonly, .

), or, less less commonly, .

3. The Time called Alla Cappella—sometimes very incorrectly misnamed Alla Breve—containing two Minim Beats in the Bar, and having for its Signature a barred Semicircle exactly similar to that used for the true Alla Breve already described (No. 1).

This Time—essentially modern—is constantly used for quick Movements, in which it is more convenient to beat twice in a Bar than four times. Antient Church Music is frequently translated into this time by modern editors, each bar of the older Notation being cut into two; but it is evidently impossible to call it 'Alla Breve,' since each bar contains the value not of a Breve but of a Semibreve only.

4. Two Crotchet or Two-four Time, sometimes, though very improperly, called 'French Common Time' (Ital. Tempo di dupla; Fr. Mesure à deux temps; Germ. Zweivierteltakt), in which each Bar contains two Beats, each represented by a Crotchet.

![{ \time 2/4 \override Score.Clef #'stencil = ##f \clef bass

e4^\rtoe e | e8[^\rtoe e e e] \bar "||" \time 4/8

e8[^\rtoe e e^^ e] | e16^\rtoe e e e e^^ e e e | s_"etc." }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/w/owwrwe38d4d88kbnm1r15m7v8a97tl3/owwrwe38.png)

In very slow Movements, written in this Time, it is not at all unusual for the Conductor to indicate four Beats in the Bar instead of two; in which case the effect is precisely the same as that which would be produced by Four Crotchet Time, taken at the same rate of movement for each Beat. It would be an excellent plan to distinguish this slow form of by the Time-Signature, ; since this sign would indicate the subsidiary Accent to be presently described.

5. Eight Quaver Time (Germ. Achtachteltakt)—that is, eight Beats in a Bar, each represented by a Quaver—is not very frequently used: but an example, marked , will be found in the PF. arrangement of the Slow Movement of Spohr's Overture to 'Faust.'

In the Orchestral Score, each Bar of this Movement is divided into two, with the barred Semicircle of Alla Cappella for its Time-Signature. It is evident that the gross contents of a Bar of this Time are equal, in value, to those of a Bar of ; but there is a great difference in the rendering, which will be explained later on.

6. Two Quaver Time (Germ. Zweiachteltakt, or Viersechszehntheiltakt), denoted by or is also very uncommon: but examples will be found in the Chorus of Witches in Spohr's Faust, and in his Symphony 'Die Weihe der Töne.'

The forms of Simple Common Time we have here described suffice for the expression of every kind of Rhythm characterised by the presence of two, four, or eight Beats in a Bar, though it would be possible, in case of necessity, to invent others. Others indeed have actually been invented by some very modern writers, under pressure of certain needs, real or supposed. The one indispensable condition is, not only that the number of Beats should be divisible by 2 or 4, but that each several Beat should also be capable of subdivision by 2 or 4, ad infinitum.[6]

II. When, however, each Beat is divisible by 3, instead of 2, the Time is called Compound Common (Germ. Gerade zusammengesetzte Takt): Common, because each Bar contains two, four, or eight Beats; Compound, because these Beats are represented, not by simple, but by dotted notes, each divisible by three. For Times of this kind, the term Compound is especially well-chosen, since the peculiar character of the Beats renders it possible to regard each Bar as an agglomeration of so many shorter Bars of Triple Time.

The forms of Compound Common Time most frequently used are—

1a Twelve-four Time (Germ. Zwölfvierteltakt), , with four Beats in the Bar, each Beat represented by a dotted Minim—or its equivalent, three Crotchets; used, principally, in Sacred Music.

2a. Twelve-eight Time (Ital. Tempo di Dodiciupla; Germ. Zwölfachteltakt), , with four Beats in the Bar, each represented by a dotted Crotchet, or its equivalent, three Quavers.

3a. Twelve-sixteen Time, ; with four Beats in the Bar, each represented by a dotted Quaver, or its equivalent, three Semiquavers.

4a. Six-two Time, ; with two beats in each Bar; each represented by a dotted Semibreve—or its equivalent, three Minims; used only in Sacred Music, and that not very frequently.

5a. Six-four Time, (Germ. Sechsvierteltakt), with two Beats in the bar, each represented by a dotted Minim—or its equivalent, three Crotchets.

6a. Six-eight Time (Ital. Tempo di Sestupla; Germ. Sechsachteltakt), with two Beats in the Bar, each represented by a dotted Crotchet—or its equivalent, three Quavers.

7a. Six-sixteen Time, , with two Beats in the Bar, each represented by a dotted Quaver—or its equivalent, three Semiquavers.

8a. Twentyfour-sixteen, with eight Beats in the Bar, each represented by a dotted Quaver—or its equivalent, three Semiquavers.

III. Unequal, or Triple Times (Ital. Tempi dispari; Fr. Mesures à trois temps; Germ. Ungerade Takt; Tripel Takt) differ from Common, in that the number of their Beats is invariably three. They are divided, like the Common Times, into two classes Simple and Compound the Beats in the first class being represented by simple notes, and those in the second by dotted ones.

The principal forms of Simple Triple Time (Germ. Einfache ungerade Takt) are—

1b. Three Semibreve Time (Ital. Tempo di Triplet di Semibrevi), , or 3, with three Beats in the Bar, each represented by a Semibreve. This form is rarely used in Music of later date than the first half of the 17th century; though, in Church Music of the School of Palestrina, it is extremely common.

2b. Three-two Time, or Three Minim Time (Ital. Tempo di Triplet di Minime) with three Beats in the Bar, each represented by a Minim, is constantly used, in Modern Church Music, as well as in that of the 16th century.

3b. Three-four Time, or Three Crotchet Time (Ital. Tempo di Tripla di Semiminime, Emiolia maggiore; Germ. Dreivierteltakt) with three Beats in the Bar, each represented by a Crotchet, is more frequently used, in modern Music, than any other form of Simple Triple Time.

4b. Three-eight Time, or Three Quaver Time (Ital. Tempo di Tripla di Crome, Emiolia minore; Germ. Dreiachteltakt) with three Beats in the Bar, each represented by a Quaver, is also very frequently used, in modern Music, for slow movements.

It is possible to invent more forms of Simple Triple Time (as , for instance), and some very modern Composers have done so; but the cases in which they can be made really useful are exceedingly rare.

IV. Compound Triple Time (Germ. Zusammengesetzte Ungeradetakt) is derived from the simple form, on precisely the same principle as that already described with reference to Common Time. Its chief forms are—

1c. Nine-four Time, or Nine Crotchet Time (Ital. Tempo di Nonupla maggiore; Germ. Neunvierteltakt) contains three Beats in the Bar, each represented by a dotted Minim—or its equivalent, three Crotchets.

2c. Nine-eight Time, or Nine Quaver Time (Ital. Tempo di Nonupla minore; Germ. Neunachteltakt) contains three Beats in a Bar, each represented by a dotted Crotchet—or its equivalent, three Quavers.

3c. Nine-sixteen Time, or Nine Semiquaver Time (Germ. Neunsechszehntheiltakt), contains three Beats in the Bar, each represented by a dotted Quaver—or its equivalent, three Semiquavers.

It is possible to invent new forms of Compound Triple Time (as ); but it would be difficult to find cases in which such a proceeding would be justifiable on the plea of real necessity.

V. In addition to the universally recognised forms of Rhythm here described, Composers have invented certain anomalous measures which call for separate notice: and first among them we must mention that rarely used but by no means unimportant species known as Quintuple Time ( or ), with five Beats in the Bar, each Beat being represented either by a Crotchet or a Quaver as the case may be. As the peculiarities of this rhythmic form have already been fully described,[7] we shall content ourselves by quoting, in addition to the examples given in vol. iii. p. 61, one beautiful instance of its use by Brahms, who, in his 'Variations on a Hungarian Air,' Op. 21, No. 2, has fulfilled all the most necessary conditions, by writing throughout in alternate Bars of Simple Common and Simple Triple Time, under a double Time-Signature at the beginning of the Movement.

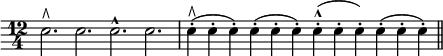

There seems no possible reason why a Composer, visited by an inspiration in that direction, should not write an Air in Septuple Time, with seven beats in a bar. The only condition needful to ensure success in such a case is, that the inspiration must come first, and prove of sufficient value to justify the use of an anomalous Measure for its expression. An attempt to write in Septuple Time, for its own sake, must inevitably result in an ignoble failure. The chief mechanical difficulty in the employment of such a Measure would lie in the uncertain position of its Accents, which would not be governed by any definite rule, but must depend, almost entirely, upon the character of the given Melody, and might indeed be so varied as to give rise to several different species of Septuple Time[8]—a very serious objection, for, after all, it is by the position of its Accents that every species of Time must be governed.[9] It was for this reason that, at the beginning of this article, we insisted upon the necessity for measuring the capacity of the Bar, not by the number of the notes it contained, but by that of its Beats: for it is upon the Beats that the Accents fall; and it is only in obedience to the position of the Beats that the notes receive them. Now it is a law that no two Accents—that is to say, no two of the greater Accents by which the Rhythm of the Bar is regulated, without reference to the subordinate stress which expresses the division of the notes into groups—no two of these greater Accents, we say, can possibly fall on two consecutive Beats; any more than the strong Accent, called by Grammarians the 'Tone,' can fall on two consecutive syllables in a word. The first Accent in the Bar—marked thus (Λ) in our examples, corresponds in Music with what is technically called the 'Tone-syllable' of a word. Where there are two Accents in the Bar, the second, marked thus, (Λ), is of much less importance. It is only by remembering this, that we can understand the difference between the Time called 'Alla Cappella,' with two Minim Beats in the Bar, and , with four Crotchet Beats: for the value of the contents of the Bar, in notes, is exactly the same, in both cases; and in both cases, each Beat is divisible by 2, indefinitely. The only difference, therefore, lies in the distribution of the Accents; and this difference is entirely independent of the pace at which the Bar may be taken.

In like manner, six Quavers may be written, with equal propriety, in a Bar of or in one of Time. But the effect produced will be altogether different; for, in the first case, the notes will be grouped in three divisions, each containing two Quavers; while, in the second, they will form two groups, each containing three Quavers. Again, twelve Crotchets may be written in a Bar of , or Time; twelve Quavers, in a Bar of , or ; or twelve Semiquavers, in a Bar of , or ; the division into groups of two notes, or three, and the effect thereby produced, depending entirely upon the facts indicated by the Time-Signature—in other words, upon the question whether the Time be Simple or Compound. For the position of the greater Accents, in Simple and Compound Time, is absolutely identical; the only difference between the two forms of Rhythm lying in the subdivision of the Beats by 2, in Simple Times, and by 3, in Compound ones. Every Simple Time has a special Compound form derived directly from it, with the greater Accents—the only Accents with which we are here concerned—falling in exactly the same places; as a comparison of the foregoing examples of Alla Breve and , ![]() and , Alla Cappella and , and , and . and , and , and , and , and , will distinctly prove. And this rule applies, not only to Common and Triple Time, but also to Quintuple and Septuple, either of which may be Simple or Compound at will. As a matter of fact, we believe we are right in saying that neither of these Rhythms has, as yet, been attempted, in the Compound form. But such a form is possible: and its complications would in no degree interfere with the position of the greater Accents.[10] For the strongest Accent will, in all cases, fall on the first Beat in the Bar; while the secondary Accent may fall, in Quintuple Time—whether Simple or Compound—either on the third or the fourth Beat; and in Septuple Time—Simple or Compound—on the fourth Beat, or the fifth—to say nothing of other places in which the Composer would be perfectly justified in placing it.[11]

and , Alla Cappella and , and , and . and , and , and , and , and , will distinctly prove. And this rule applies, not only to Common and Triple Time, but also to Quintuple and Septuple, either of which may be Simple or Compound at will. As a matter of fact, we believe we are right in saying that neither of these Rhythms has, as yet, been attempted, in the Compound form. But such a form is possible: and its complications would in no degree interfere with the position of the greater Accents.[10] For the strongest Accent will, in all cases, fall on the first Beat in the Bar; while the secondary Accent may fall, in Quintuple Time—whether Simple or Compound—either on the third or the fourth Beat; and in Septuple Time—Simple or Compound—on the fourth Beat, or the fifth—to say nothing of other places in which the Composer would be perfectly justified in placing it.[11]

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

In a few celebrated cases more numerous, nevertheless, than is generally supposed Composers have produced particularly happy effects by the simultaneous employment of two or more different kinds of Time. A very simple instance will be found in Handel's so-called 'Harmonious Blacksmith,' where one hand plays in Four-Crotchet Time (![]() ) and the other in . A more ingenious combination is found in the celebrated Movement in the Finale of the First Act of 'Il Don Giovanni,' in which three distinct Orchestras play simultaneously a Minuet in Time, a Gavotte in , and a Waltz in , as in Ex. 1 on previous page; the complexity of the arrangement being increased by the fact that each three bars of the Waltz form, in their relation to each single bar of the Minuet, one bar of Compound Triple Time (); while in relation to each single bar of the Gavotte, each two bars of the Waltz form one bar of Compound Common Time ().

) and the other in . A more ingenious combination is found in the celebrated Movement in the Finale of the First Act of 'Il Don Giovanni,' in which three distinct Orchestras play simultaneously a Minuet in Time, a Gavotte in , and a Waltz in , as in Ex. 1 on previous page; the complexity of the arrangement being increased by the fact that each three bars of the Waltz form, in their relation to each single bar of the Minuet, one bar of Compound Triple Time (); while in relation to each single bar of the Gavotte, each two bars of the Waltz form one bar of Compound Common Time ().

A still more complicated instance is found in the Slow Movement of Spohr's Symphony, 'Die Weihe der Töne' (Ex. 2 on previous page); and here again the difficulty is increased by the continuance of the slow Tempo—Andantino—in the part marked , while the part marked Allegro starts in Doppio movimento, each Quaver being equal to a Semiquaver in the Bass.

Yet these complications are simple indeed when compared with those to be found in Palestrina's Mass 'L'homme armé,' and in innumerable Compositions by Josquin des Pres, and other writers of the 15th and 16th centuries; triumphs of ingenuity so abstruse that it is doubtful whether any Choristers of the present day could master their difficulties, yet all capable of being expressed with absolute certainty by the various forms of Mode, Time, and Prolation, invented in the Middle Ages, and based upon the same firm principles as our own Time-Table. For, all the mediæval Composers had to do, for the purpose of producing what we call Compound Common Time, was to combine Imperfect Mode with Perfect Time, or Imperfect Time with the Greater Prolation; and, for Compound Triple Time, Perfect Mode with Perfect Time, or Perfect Time with the Greater Prolation.[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ Here, again, we meet with another curious anomaly; for the word 'Mode' is also applied, by mediæval writers, to the peculiar forms of Tonality which preceded the invention of the modern Scale.

- ↑ See Mode, Prolation, and Vol. ii. pp. 471b–472a.

- ↑ Strictly speaking, the term 'Bar' applies only to the lines drawn perpendicularly across the Stave, for the purpose of dividing a Composition into equal portions, properly called 'Measures.' But, in common language, the term 'Bar' is almost invariably substituted for 'Measure,' and consequently used to denote not only the perpendicular lines, but also the Music contained between them. It is in this latter sense that the word is used throughout the present article.

- ↑ Not a 'capital C, for Common Time,' as neophytes sometimes suppose.

- ↑ Not to be mistaken for the 'Tempo ordinario' so often used by Handel, in which the term 'Tempo' refers to pace, and not to rhythm, or measure.

- ↑ This law does not militate against the use of Triplets, Sextoles, or other groups containing any odd number of notes, since these abnormal groups do not belong to the Time, but are accepted as infractions of its rules.

- ↑ See Quintuple Time.

- ↑ See the remarks on an analogous uncertainty in Quintuple Time. Vol. iii. p. 61b.

- ↑ The reader will bear in mind that we are here speaking of Accent, pur et simple, and not of emphasis. A note may be emphasised, in any part of the Bar; but the quiet dwelling upon it which constitutes true Accent—Accent analogous to that used in speaking—can only take place on the accented Beat, the position of which is invariable. Hence it follows that the most strongly accented notes in a given passage may also be the softest. In all questions concerning Rhythm, a clear understanding of the difference between Accent—produced by quietly dwelling on a note—and Emphasis produced by forcing it, is of the utmost importance.

- ↑ Compound Quintuple Rhythm would need, for its Time-Signature the fraction or ; and Compound Septuple Rhythm, or . Tyros are sometimes taught the perfectly correct though by no means satisfactory 'rule of thumb,' that all fractions with a numerator greater than 5 denote Compound Times.

- ↑ See Time-beating.