Submerged Forests/Chapter 1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY

Most of our sea-side places of resort lie at the mouths of small valleys, which originally gave the fishermen easy access to the shore, and later on provided fairly level sites for building. At such places the fishermen will tell you of black peaty earth, with hazel-nuts, and often with tree-stumps still rooted in the soil, seen between tide-marks when the overlying sea-sand has been cleared away by some storm or unusually persistent wind. If one is fortunate enough to be on the spot when such a patch is uncovered this "submerged forest" is found to extend right down to the level of the lowest tides. The trees are often well-grown oaks, though more commonly they turn out to be merely brush-wood of hazel, sallow, and alder, mingled with other swamp- plants, such as the rhizomes of Osmuuda.

These submerged forests or "Noah's Woods" as they are called locally, have attracted attention from early times, all the more so owing to the existence of an uneasy feeling that, though like most other geological phenomena they were popularly explained by Noah's deluge, it was difficult thus to account for trees rooted in their original soil, and yet now found well below the level of high tide.

It may be thought that these flats of black peaty soil though curious have no particular bearing on scientific questions. They show that certain plants and trees then lived in this country, as they do now; and that certain animals now extinct in Britain once flourished here, for bones and teeth of wild-boar, wolf, bear, and beaver are often found. Beyond this, however, the submerged forests seem to be of little interest. They are particularly dirty to handle or walk upon; so that the archaeologist is inclined to say that they belong to the province of geology, and the geologist remarks that they are too modern to be worth his attention; and both pass on.

Should we conquer our natural repugnance for such soft and messy deposits, and examine more closely into these submerged forests, they turn out to be full of interest. It is largely their extremely inconvenient position, always either wet or submerged, that has made them so little studied. It is necessary to get at things more satisfactorily than can be done by kneeling down on a wet muddy foreshore, with the feeling that one may be caught at any time by the advancing tide, if the study is allowed to become too engrossing. But before leaving for a time the old land-surface exposed between tide marks, it will be well to note that we have already gained one piece of valuable information from this hasty traverse. We have learnt that the relative level of land and sea has changed somewhat, even since this geologically modern deposit was formed.

Geologists, however, sometimes speak of the submerged forests as owing their present position to various accidental causes. Landslips, compression of the underlying strata, or the removal of some protecting shingle-beach or chain of sand-dunes are all called into play, in order to avoid the conclusion that the sea-level has in truth changed so recently. The causes above mentioned have undoubtedly all of them affected certain localities, and it behoves us to be extremely careful not to be misled. Landslips cannot happen without causing some disturbance, and a careful examination commonly shows no sign of disturbance, the roots descending unbroken into the rock below. It is also evident in most cases that no landslip is possible, for the "forest" occupies a large area and lies nearly level.

Compression of the underlying strata, and consequent sinking of the land-surface above, is however a more difficult matter to deal with. Such compression undoubtedly takes place, and some of the appearances of subsidence since the Roman invasion are really cases of this sort. Where the trees of the submerged forest can be seen rooted into hard rock, or into firm undisturbed strata of ancient date, there can, however, be no question that their position below sea-level is due to subsidence of the land or to a rise of the sea, and not to compression. But in certain cases it is found that our submerged land-surface rests on a considerable thickness of soft alluvial strata, consisting of alternate beds of silt and vegetable matter. Here it is perfectly obvious that in course of time the vegetable matter will decay, and the silt will pack more closely, thus causing the land-surface above slowly to sink. Subsidence of this character is well known in the Fenland and in Holland, and we must be careful not to be misled by it into thinking that a change of sea-level has happened within the last few centuries. The sinking of the Fenland due to this cause amounts to several feet.

The third cause of uncertainty above mentioned, destruction of some bank which formerly protected the forest, needs a few words. It is a real difficulty in some cases, and is very liable to mislead the archaeologist. We shall see, however, that it can apply only to a very limited range of level.

Extensive areas of marsh or meadow, protected by a high shingle-beach or chain of sand-dunes, are not uncommon, especially along our eastern coast. These marshes may be quite fresh, and even have trees growing on them, below the level of high tide, as long as the barrier remains unbroken. The reason of this is obvious. The rise and fall of the tide allows sea water to percolate landward and the fresh water to percolate seaward; but the friction is so great as to obliterate most of the tidal wave. Thus the sea at high tide is kept out, the fresh water behind the barrier remaining at a level slightly above that of mean tide, and just above that level we may find a wet soil on which trees can grow. But, and here is the important point, a protected land-surface behind such a barrier can never lie below the level of mean tide; if it sinks below that level it must immediately be flooded, either by fresh water or by sea water. This rule applies everywhere, except to countries where evaporation exceeds precipitation; only in such countries, Palestine for instance, can one find sunk or Dead Sea depressions below mean-tide level of the open sea.

The submerged forest that we have already examined stretched far below the level of mean tide, in fact we followed it down to the level of the lowest spring tides. Nothing but a change of sea-level will account for its present position. In short, the three objections above referred to, while teaching us to be careful to examine the evidence in doubtful cases, cannot be accepted as any explanation of the constant and widespread occurrence of ancient land-surfaces passing beneath the sea.

We have thus traced the submerged forest down to low-water mark, and have seen it pass out of our reach below the sea. We naturally ask next, What happens at still lower levels? It is usually difficult to examine deposits below the sea-level; but fortunately most of our docks are excavated just in such places as those in which the submerged forests are likely to occur. Docks are usually placed in the wide, open, estuaries, and it is often necessary nowadays to carry the excavations fully fifty feet below the marsh-level. Such excavations should be carefully watched, for they throw a flood of light on the deposits we wish to examine.

Every dock excavation, however, does not necessarily cut through the submerged forests, for channels in an estuary are constantly shifting, and many of our docks happen to be so placed as to coincide with comparatively modern silted-up channels. Thus at Kings Lynn they hit on an old and forgotten channel of the Ouse, and the bottom of the dock showed a layer of ancient shoes, mediaeval pottery, and suchlike—interesting to the archaeologist, but not what we are now in search of. At Devonport also the recent dock extension coincided with a modern silted-up channel. In various other cases, however, the excavations have cut through a most curious alternation of deposits, though the details vary from place to place.

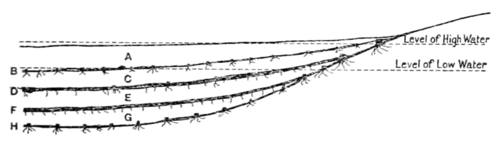

The diagram (fig. 1) shows roughly what is found. We will suppose that the docks are placed, as is usually the case, on the salt marshes, but with their landward edge reaching the more solid rising ground, on which the warehouses, etc., are to be built. Beginning at or just above the level of ordinary high-water of spring tides, the first deposit to be cut through is commonly a bed (A) of estuarine silt or warp with remains of cockles, Scrobicularia, and salt-marsh vegetation. Mingled with these we find drifted wreckage, sunk boats, and miscellaneous rubbish, all belonging to the historic period. The deposits suggest no change of sea-level, and are merely the accumulated mud which has gradually blocked and silted up great part of our estuaries and harbours during the last 3500 years.

This estuarine silt may continue downward to a level below mean tide, or perhaps even to low-water level; but if the sequence is complete we notice below it a sudden change to a black peaty soil (B), full of vegetable matter, showing sallows, alder, and hazel rooted in their position of growth. In this soil we may also find seams of shell-marl, or chara-marl, such as would form in shallow pools or channels in a freshwater marsh. This black peaty soil is obviously the same "submerged forest" that we have already examined on the foreshore at the mouth of the estuary; the only difference being that in the more exposed situation the waves of the sea have cleared away the overlying silt, thus laying bare the land surface beneath. In the dock excavations, therefore, the submerged forest can be seen in section and examined at leisure.

The next deposit (C), lying beneath the submerged forest, is commonly another bed of estuarine silt, extending to a depth of several feet and carrying our observations well below the level of low-water. Then comes a second land-surface (D), perhaps with trees differing from those of the one above; or it may be a thick layer of marsh peat. More silt (E) follows; another submerged forest (F); then more estuarine deposits (G); and finally at the base of the channel, fully 50 feet below the level of high-water, we may find stools of oak (H) still rooted in the undisturbed rock below.

As each of these deposits commonly extends continuously across the dock, except where it happens to abut against the rising ground, it is obvious that it is absolutely cut off from each of the others. The lowest land-surface is covered by laminated silts, and that again is sealed up by the matted vegetation of the next growth. Thus nothing can work its way down from layer to layer, unless it be a pile forcibly driven down by repeated blows. Materials from the older deposits in other parts of the estuary may occasionally be scoured out and re-deposited in a newer layer; but no object of a later period will find its way into older beds.

Thus we have in these strongly marked alternations of peat and warp an ideal series of deposits for the study of successive stages. In them the geologist should be able to study ancient changes of sea-level, under such favourable conditions as to leave no doubt as to the reality and exact amount of these changes. The antiquary should find the remains of ancient races of man, sealed up with his weapons and tools. Here he will be troubled by no complications from rifled tombs, burials in older graves, false inscriptions, or accidental mixture. He ought here to find also implements of wood, basket- work, or objects in leather, such as are so rarely preserved in deposits above the water-level, except in a very dry country.

To the zoologist and botanist the study of each successive layer should yield evidence of the gradual changes and fluctuations in our fauna and flora, during early periods when man, except as hunter, had little influence on the face of nature. If I can persuade observers to pay more attention to these modern deposits my object is secured, and we shall soon know more about some very obscure branches of geology and archaeology.

I do not wish to imply that excellent work has not already been done in the examination of these deposits. Much has been done; but it has usually been done unsystematically, or else from the point of view of the geologist alone. What is wanted is something more than this—the deposits should be examined bed by bed, and nothing should be overlooked, whether it belong to geology, archaeology or natural history. We desire to know not merely what was the sea-level at each successive stage, but what were the climatic conditions. We must enquire also what the fauna and flora were like, what race of man then inhabited the country, how he lived, what weapons and boats he used, and how he and all these animals and plants were able to cross to this country after the passing away of the cold of the Glacial period.

To certain of the above questions we can already make some answer; but before dealing with conclusions, it will be advisable to give some account of the submerged land-surfaces known in various parts of Britain. This we will do in the next chapters.

Before going further it will be well to explain and limit more definitely the field of our present enquiry. It may be said that there are "submerged forests" of various geological dates, and this is perfectly true. The "dirt-bed" of the Isle of Purbeck, with its upright cycad-stems, was at one time a true submerged forest, for it is overlain by various marine strata, and during the succeeding Cretaceous period it was probably submerged thousands of feet. Every coal seam with its underlying soil or "underclay" penetrated by stigmarian roots was also once a submerged forest. Usage, however, limits the term to the more recent strata of this nature, and to these we will for the present confine our attention. We do not undertake a description of the earlier Cromer Forest-bed, or even of the Pleistocene submerged forests containing bones of elephant and rhinoceros and shells of Corbicula fluminalis. These deposits will, however, be referred to where from their position they are liable to be confounded with others of later date.