Submerged Forests/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II

THE THAMES VALLEY

In the last chapter an attempt was made to give a general idea of the nature of the deposits ; we will now give actual examples of what has been seen. Unfortunately we cannot say "what can be seen," for the lower submerged forests are only visible in dock excavations. As these works are carried well below the sea-level and have to be kept dry by pumping, it is impossible for them to remain open long, and though new excavations are constantly being made, the old ones are nearly always hidden within a few weeks of their becoming visible. Of course these remarks do not apply to the highest of these submerged land-surfaces, which can be examined again and again between tide-marks, whenever the tide is favourable and the sand of the foreshore has been swept away.

The most convenient way of dealing with the evidence will perhaps be to describe first what has been seen in the estuary of the Thames. Then in later chapters we will take the localities on our east coast and connected with the North Sea basin. Next we will speak of those on the Irish Sea and English Channel. Lastly, the numerous exposures on the west or Atlantic coast will require notice, and with them may be taken the corresponding deposits on the French coast. Each of these groups will require a separate chapter.

The Thames near London forms a convenient starting point, for the numerous dock-excavations, tunnels, deep drains and dredgings have laid open the structure of this valley and its deposits in an exceptionally complete way. The published accounts of the excavations in the Thames Valley are so voluminous that it is impossible here to deal with them in any detail; we must therefore confine ourselves to those which best illustrate the points we have in view, choosing modern excavations which have been carefully watched, noted, and collected from rather than ancient ones.

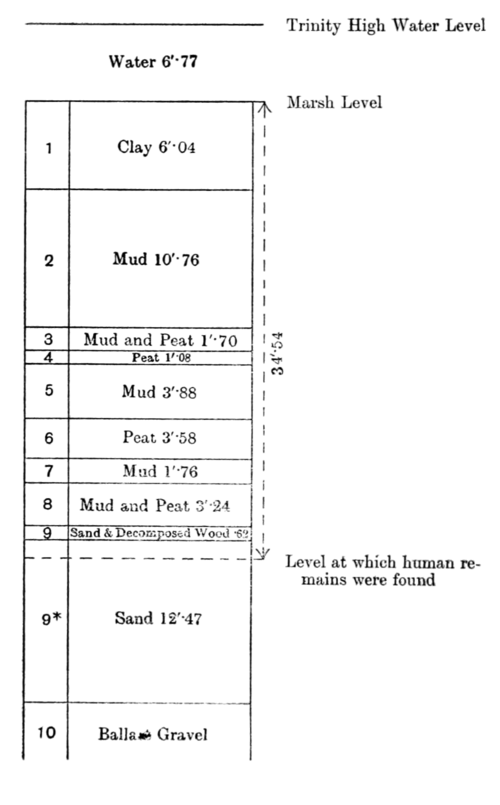

We cannot do better than take as an illustration of the mode of occurrence and levels of the submerged land-surfaces the section seen in the excavation of Tilbury Docks, for this was most carefully noted by the engineers, and was visited by two competent observers, Messrs. W. Whitaker and F. C. J. Spurrell. This excavation is of great scientific importance, for it led to the discovery of a human skeleton beneath three distinct layers of submerged peat, and these remains have been most carefully studied by Owen and Huxley, and more recently by Professor Keith.

The section communicated to Sir Richard Owen by Mr Donald Baynes, the engineer superintending the excavation at the time of the discovery, is shown in the diagram on p. 14. As Mr Baynes himself saw part of the skeleton in the deposit, his measured section is most important as showing its exact relation to the submerged forests. It is also well supplemented by the careful study of the different layers made by Mr Spurrell, for though his specimens did not come from exactly this part of the docks, the various beds are traceable over so large an area that there is no doubt as to their continuity.Owen thought that this skeleton belonged to a man of the Palaeolithic period, considering it contemporaneous with the mammoth and rhinoceros found elsewhere in the neighbourhood. Other geological writers showed however that these deposits were much more modern, and some of them spoke somewhat contemptuously of their extremely recent date. But Huxley saw the importance of this "river-drift man" as an ancient and peculiar race, and Professor Keith has more recently drawn especial attention to the well-marked characteristics of the type. The skeleton is not of Palaeolithic date, but neither is it truly modern; other examples have turned up in similar deposits elsewhere.

We will now describe more fully the successive layers met with in Tilbury Docks, condensing the account from that given by Messrs. Spurrell and Whitaker, and using where possible the numbers attached by the engineer to the successive beds.

It will be noticed that the marsh-level lies several feet below Trinity high water. Below the sod of the marsh came a bed of fine grey tidal clay (1), in which at a depth of seven feet below the surface Mr Spurrell noted, in one part of the docks, an old grass-grown surface strewn with Roman refuse, such as tiles, pottery, and oyster shells. This fixes the date of the layer above as post-Roman; but the low position of the Roman land-surface, now at about mean-tide level, is due in great part to shrinkage since the marsh was embanked and drained—it is unconnected with any general post-Roman subsidence of the land.

Beneath the Roman layer occurs more marsh-clay and silt (2), resting on a thin peat (4) which according to Mr Whitaker is sometimes absent. Then follows another bed of marsh-clay (5), shown by the engineer as four feet thick, but which in places thickens to six or seven feet. Below this is a thick mass (6) of reedy peat (the "main peat" of Mr Spurrell), which is described as consisting mainly of Phragmites and Sparganium, with layers of moss and fronds of fern. The other plants observed in this peat were the elder, white-birch, alder and oak. Associated with them were found several species of freshwater snails and a few land forms; but the only animal or plant showing any trace of the influence of salt water was Hydrobia ventrosa, a shell that requires slightly brackish water.

The main peat rests on another bed of estuarine silt (7 and 8), which seems to vary considerably in thickness, from 5 to 12 feet. It is not quite clear from the descriptions whether the "thin woody peat" of Mr Whitaker and the "sand with decayed wood" (9) of the engineer represent a true growth in place, like the main peat; it is somewhat irregular and tends to abut against banks of sand (9*) rising from below. In one of these banks, according to Mr Spurrell, the human skeleton was found.

The contents of the sand (other than the skeleton) included Bythinia and Succinea; and as Mr Spurrell calls it a "river deposit," it apparently did not yield estuarine shells, like the silts above. The sub- angular flint gravel (10) below has all the appearance of a river gravel; it may be from 10 to 20 feet thick, and rests on chalk only reached in borings.

The floor of chalk beneath these alluvial deposits lies about 60 or 70 feet below the Ordnance datum in the neighbourhood of Tilbury and Gravesend, and in the middle of the ancient channel of the Thames it may be 10 feet lower; but there is no evidence of a greater depth than this. We may take it therefore that here the Thames once cut a channel about 60 feet below its modern bed. We cannot say, however, from this evidence alone that the sea-level then was only 60 feet below Ordnance datum, for it is obvious that it may have been considerably lower. If, as we believe, the southern part of the North Sea was then a wide marsh, the Thames may have followed a winding course of many miles before reaching the sea, then probably far away, in the latitude of the Dogger Bank. This must be borne in mind: we know the minimum extent of the change of level; but its full amount has to be ascertained from other localities.

This difficulty has seemed of far greater importance than it really is, and some geologists have suggested that at this period of maximum elevation, England stood several hundred feet higher above the sea than it does now. I doubt if such can have been the case. Granting that the sea may have been some 300 miles away from Tilbury, measured along the course of the winding river, this 300 miles would need a very small fall per mile, probably not more than an inch or two. The Thames was rapidly growing in volume, from the access of tributaries, and was therefore flowing in a deeper and wider channel, which was cut through soft alluvial strata; it therefore required less and less fall per mile. Long before it reached the Dogger it probably flowed into the Rhine, then containing an enormous volume of water and draining twice its present catchment area.

The clean gravel and sand which occupy the lower part of the ancient channel at Tilbury require to be more closely examined, for it is not clear that they are, as supposed, of fluviatile origin; they may quite well be estuarine. In the sand Mr Spurrell found the freshwater shells Bythinia and Succinea, and in it was also found the human skeleton described by Owen; but, according to Mr Spurrell, on the surface of this sand lay a few stray valves of the estuarine Scrobicularia and of Tellina. The bottom deposits were probably laid down in a tidal river; but whether within the influence of the salt water is doubtful.

As far as the Tilbury evidence goes it suggests a maximum elevation of the land of about 80 feet above its present level; but we will return to this question when we have dealt with the other rivers flowing more directly into deep sea. The animals and plants found at Tilbury were all living species.

It is unnecessary here to discuss more fully the submerged forests seen in dock and other excavations in the Thames flats, for they occupy a good many pages in the Geology of London published by the Geological Survey. Even 250 years ago, the hazel trees were noticed by the inquisitive Pepys during one of his official visits to the dockyards, and later writers are full of remarks on the ancient yew trees and oaks found well below the sea-level. Most of these early accounts are, however, of little scientific value.