The Boy Travellers in the Russian Empire/Chapter 16

CHAPTER XVI.

"THERE are many errors in the popular mind of England and America concerning the system of exile to Siberia," said Mr. Hegeman, as he settled into a chair to begin his discourse on this interesting subject.

"One error is that exiles are treated with such cruelty that they do not live long; that they are starved, beaten, tortured, and otherwise forced into an early death.

"No doubt there have been many cases of cruelty just as there have been in prisons and other places of involuntary residence all over the globe and among all nations. Exiles are prisoners, and the lot of a prisoner depends greatly upon the character of his keeper, without regard to the country or nation where he is imprisoned. Siberia is no exception to the rule. With humane officials in power, the life of the exiles is no worse, generally speaking, than is that of the inmates of a prison in other lands; and with brutal men in authority the lot of the exile is doubtless severe.

"In the time of the Emperor Nicholas there was probably more cruelty in the treatment of exiles than since his death; but that he invented systems of torture, or allowed those under him to do so, as has been alleged, is an absurdity.

"Let me cite a fact in support of my assertion. After the revolution of 1825, just as Nicholas ascended the throne, two hundred of the conspirators were exiled to hard labor for life. They were nearly all young men, of good families, and not one of them had ever devoted a day to manual occupation. Reared in luxury, they were totally unfitted for the toil to which they were sentenced; and if treated with the cruelty that is said to be a part of exile, they could not have lived many months.

"The most of them were sent to the mines of Nertchinsk, where they were kept at labor for two years. Afterwards they were employed in a polishing-mill at Chetah and on the public roads for four or five years, and at the end of that time were allowed to settle in the villages and towns, making their living in any way that was practicable. Some of them were joined by their wives, who had property in their own right (the estates of the exiles were confiscated at the time of their banishment), and those thus favored by matrimonial fortune were able to set up fine establishments.

"Some of the Decembrists, as these particular exiles were called, from the revolution having occurred in December, died within a few years but the most of them lived to an advanced age. When Alexander II.

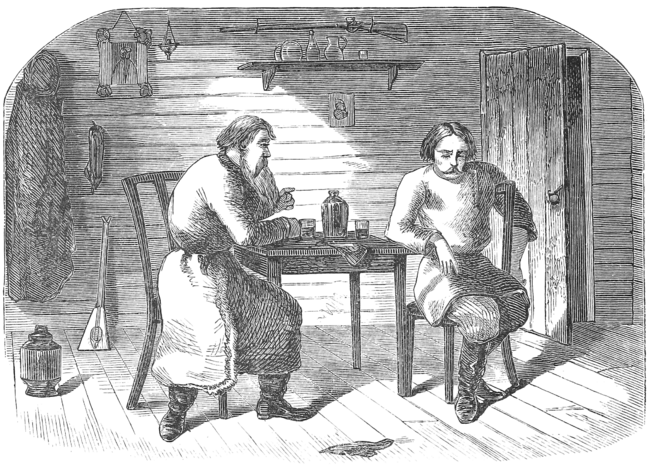

INTERIOR OF AN EXILES HUT.

ascended the throne, in 1856, all the Decembrists were pardoned. Some of them returned to European Russia after thirty-one years of exile, but they found things so changed, and so many of their youthful companion dead, that they wrote back and advised those who were still in Siberia to stay there. My first visit to Siberia was in 1866, forty-one years after the December revolution. At that time there were ten or twelve of the Decembrists still living, all of them venerable old men. One was a prosperous wine-merchant at Irkutsk; another had made a fortune as a timber-merchant; others were comfortable, though not wealthy; and two or three were in humble, though not destitute circumstances. Now, if they had been treated with the cruelty that is alleged to be the lot of all Siberian exiles, do you think any of them would have reached such an advanced age?"

Silence gave assent to the query. After a short pause, Frank asked what was the social standing of these exiles, the Decembrists.

"It was nearly, though not quite, what it was in European Russia before their exile," was the reply. "They were received in the best

EXILES PASSING THROUGH A VILLAGE.

Siberian families, whether official or civilian, and were on terms of friendship with the officials in a private way. They were not invited to strictly official ceremonies, and this was about the only difference between their treatment and that of those who were not exiles. Of course I refer to the time when they were settled in the towns, after their term of forced labor was ended. Before that they were just like any other prisoners condemned to the same kind of servitude.

"There were two of the Decembrists (Prince Troubetskoi and Prince Volbonskoi) whose wives were wealthy, and followed their husbands into exile. When relieved from labor and allowed their personal liberty, these princes came to Irkutsk and built fine houses. They entertained handsomely, were visited by the officials, went very much into society, and in every way were as free as any one else, except that they were forbidden to leave Siberia. Nicholas was not of a forgiving disposition, and not till he died were the Decembrists free to return to St. Petersburg.

"A bit of social gossip adds to the interest of the Siberian life of Prince Volbonskoi. There was some incompatibility of temper between the prince and his wife, and for a long time they were not particularly friendly. She and the children and servants occupied the large and elegantly furnished house, while the Prince lived in a small building in the court-yard. He had a farm near the town, and sold to his wife such of the produce as she needed for household use."

Fred wished to know how many kinds of people are sent to Siberia.

"There are three classes of exiles," was the reply: "political, religious, and criminal offenders. The political ones include Nihilists and other revolutionists, and of course there is a great majority of Poles among this class; the religious exiles are certain sects of fanatics that the Government wishes to suppress; and the criminal ones are those who offend against society in all sorts of ways. None of them are ever called 'prisoners' or 'criminals' while in Siberia, and it is not often you hear them termed 'exiles.' In ordinary conversation they are called 'unfortunates,' and in official documents they are classed as 'involuntary emigrants.'

"There are about ten thousand 'involuntary emigrants' going every year from European Russia to Siberia. These include criminals of all kinds, a few religious offenders of the fanatical sort, and some Nihilists and other revolutionists. At every revolution in Poland the number of exiles for the next few years is greatly increased. After the revolution of 1863 twenty-four thousand Poles were sent to Siberia, and other revolutions have contributed a proportionate number."

"Do they all have the same kind of sentence, without regard to their offences?" one of the youths asked.

"Not at all," was the reply. "The lowest sentence is to three years' banishment, and the highest is to hard labor for life. Sentences vary all the way between these two categories—for five, ten, fifteen, or twenty years' banishment without labor, or for the same number of years with

A TOWN BUILT BY EXILES.

BANISHED FOR FIVE YEARS.

labor. A man may be sentenced to a given number of years' banishment, of which a certain designated portion shall be to hard labor, or he may be sentenced for life, with no hard labor at all. The punishment is varied greatly, and, from all I hear, the sentence is rarely carried out to its fullest degree. The time of exile is not lessened until a general pardon liberates entire classes, but the severity of the labor imposed is almost always lightened.

"Then, too, the exiles are distributed throughout the country, and not allowed to gather in large numbers. The object of the exile system is to give a population to Siberia, and not to cause the death of the banished individual. Every effort is made to induce the exile to forget the causes that brought him to Siberia, and to make him a good citizen in his new home. His wife and children may follow or accompany him into exile at government expense, but they cannot return to European Russia until he is personally free to do so. This permission is denied in the cases of the worst criminals who are sentenced to hard labor and must leave their families behind.

"Figures I was glancing at this morning show that in one year 16,889 persons were sent to Siberia, accompanied by 1080 women and children over fifteen years old, and by 1269 under that age. Of the whole number of exiles mentioned, 1700 were sentenced to hard labor, and 1624 were drunkards and tramps. The status of the rest is not given, but they were probably sentenced to various terms of deportation without labor.

"I should say further, in regard to this family matter, that an exile is regarded as a dead man in the place from which he is sent, and his wife, if she remains in Europe, is legally a widow, and may marry again if she chooses. The wifeless man in Siberia is urged to marry and become the head of a family, and whenever he marries, the Government gives him a grant of land and aids him in establishing a home. As long as an exile conducts himself properly, and does not try to escape, he does not find existence in Siberia particularly dreadful, provided, of course, he has not been sent to hard labor, and the officers in charge of him are not of a cruel disposition."

Frank asked what work was done by those sentenced to hard labor, and how the men lived who were simply exiles and had not a labor sentence attached.

"Those sentenced to katorga, or hard labor, are employed in mines or on roads, and in mills and factories of various kinds. Several years ago an order was issued that exiles should no longer be kept at work in mines, but I am told on pretty good authority that this humane decree has been revoked since the rise of Nihilism. In the mines of Nertchinsk, in the

latter part of the last century and the early part of the present one, the labor was fearful. The prisoners were in pairs, chained together; they were often kept working in mud and water for fourteen or sixteen hours daily; their lodgings were of the poorest character, and their food was nothing but black bread and occasionally a little cabbage soup. The great mortality in the mines attracted the attention of the Government, and the evils were remedied.

"Down to the end of the last century, criminals condemned to the mines were marked by having their nostrils slit open, but this barbarity has not been practised for a long time.

"Those sentenced to lighter labor are engaged in trades, such as making shoes, clothing, or other articles. Those who are simply exiled without labor can work at their trades, if they have any, preciseiy as they would do at home. If they are educated men they may practise their professions, give instruction to young people, or find employment with merchants as book-keepers or other assistants in business. Some years ago the permission for exiles to engage in teaching anything else than music, drawing and painting was revoked, when it was discovered that some of them had been using their opportunities to spread revolutionary doctrines. Whether this order is yet in force I do not know.

"The next thing to hard labor in Siberia is the sentence to become 'a perpetual colonist.' This means that the exile is to make his living by tilling the soil, hunting, fishing, or in any other way that may be permitted by the authorities; he must be under the eye of the police, to whom he reports at regular intervals, and he must not go beyond certain limits that are prescribed to him.

"The perpetual colonist has a grant of land, and is supplied with tools and materials for building a house; he receives flour and other provisions for three years, and at the end of that time he is supposed to be able to take care of himself. Where he is sent to a fertile part of the country, his life is not particularly dreadful, though at best it is a severe punishment for a man who has been unaccustomed to toil, and has lived in luxury up to the time of being sent to Siberia. Many of these colonists are sent to the regions in or near the Arctic circle, where it is almost continuous winter, and the opportunities for agriculture are very small. Only a few things can be made to grow at all, and the exile doomed to such a residence must depend mainly upon hunting and fishing. If game is scarce, or the fishing fails, there is liable to be great suffering among these unhappy men.

"The friends of an exile may send him money, but not more than twenty-five roubles (about $20) a month. As before stated, the wife of an exile may have an income separate from that of her husband, and if she chooses to spend it they may live in any style they can afford.

"Many criminal and political exiles are drafted into the army in much the same way that prisons in other countries are occasionally emptied when recruits are wanted. They receive the same pay and treatment as other soldiers, and are generally sent to distant points, to diminish the chances of desertion. Most of these recruits are sent to the regiments in the Caucasus and Central Asia, and a good many are found in the Siberian regiments.

"All money sent to exiles must pass through the hands of the officials. It is a common complaint, and probably well founded, that a goodly part of this money sticks to the hands that touch it before it reaches its rightful owner. The same allegation is made concerning the allowances of

EXILES LEAVING MOSCOW.

money and flour, just enough to support life, that are given to exiles who are restricted to villages and debarred from remunerative occupation."

"Did you personally meet many exiles while you were in Siberia?" Frank inquired.

"I saw a great many while I was travelling through the country," Mr. Hegeman answered, "and in some instances had conversations with them. At the hotel where I stopped in Irkutsk the clerk was an exile, and so was the tailor that made an overcoat for me. Clerks in stores and shops, and frequently the proprietors, were exiles; the two doctors that had the largest practice were 'unfortunates' from Poland, and so was the director of the museum of the Geographical Society of Eastern Siberia. Some of the isvoshchiks were exiles. On one occasion an isvoshchik repeated the conversation which I had with a friend in French, without any suspicion that he understood what we were saying. Hardly a day passed that I did not meet an 'unfortunate,' and I was told that much of the refinement of society in the Siberian capital was due to the exiles. In talking with them I was careful not to allude in any way to their condition, and if they spoke of it, which was rarely the case, I always managed to turn the conversation to some other subject.

"When on the road I met great numbers of exiles on their way east-ward. Five-sixths of them were in sleighs or wagons, as it has been found cheaper to have them ride to their destinations than to walk. Those on foot were accompanied by their guards, also on foot; there was a wagon

TAGILSK, CENTRE OF IRON-MINES OF SIBERIA.

or sleigh in the rear for those who were ill or foot-sore, and there were two or more men on horseback to prevent desertions. Formerly all prisoners were obliged to walk to their destinations. The journey from St. Petersburg to Nertchinsk required two years, as it covered a distance of nearly five thousand miles."

"Do they sleep in the open air when on the road, or are they lodged in houses?" inquired Fred.

"There are houses every ten or fifteen miles, usually just outside the villages," was the reply. "In these houses the prisoners are lodged. The places are anything but inviting, as the space is not large. No attempt is made to keep it clean, and the ventilation is atrocious. In winter it is a shelter from the cold, but in summer the prisoners greatly prefer to sleep out-of-doors. Sometimes the guards will not grant permission for them to do so, owing to the danger of desertion, but the scruples of the guards may be overcome by a promise obtained from all that no attempt will be made to escape, and that everybody shall watch everybody else.

"From fifty to two hundred exiles form a batch or convoy. They are sent off once or twice a week, according to the number that may be on hand. All the convoys of exiles go to Omsk, in Western Siberia, and from there they are distributed throughout the country—some in one direction

and some in another. Those that travel on foot rest every third day, and the ordinary march of a day is about fifteen miles; those in carriages are hurried forward, only resting on Sundays, and not always then."

"Do the guards of a convoy go all the way through with the prisoners?"

"No, they do not; they go from one large town to another. In the large towns there are prisons which serve as depots where exiles are accumulated, and the distribution of prisoners is generally made from these points. The officers and soldiers in charge of a convoy take their prisoners to one of these depots and deliver up their charges; receipts are given for the number of men delivered, just as for so many boxes or bales of goods. The guard can then return to its starting-point, and the prisoners are locked up until the convoy is ready for the road again.

"The guards are responsible for their prisoners, both from escape and injury. If a man dies on the road his body is carried to the next station for burial, so that the station-master and others may certify to the death; and if a man is killed while attempting to escape, the same disposition must be made of his body.

"Some years ago a Polish lady who was going into exile fell from a boat while descending a river. She had a narrow escape from drowning, and the officer in charge of her was very much alarmed. When she was rescued from the water, he said to her, 'I shall be severely punished if you escape or any accident happens to you. I have tried to treat you kindly, and beg of you, for my sake, not to drown yourself or fall into the river again.'"

"But don't a good many escape from Siberia, and either go back to their homes or get to foreign countries?"

"The number of escapes is not large," Mr. Hegeman answered, "as the difficulties of getting out of the country are very great. In the first place, there is the immense distance from the middle of Siberia to Moscow or St. Petersburg, or, worse still, to Poland. Nobody can hire horses at a station without showing his paderojnia, and this is only issued by the police-master, who knows the name and probably the face of every exile in his district. Even if a man gets a paderojnia by fraud, his absence would soon be discovered, and his flight can be stopped by the use of the telegraph.

"If an exile should try to get out of the country by going northward he would be stopped by the shores of the Arctic Ocean. If he goes to the south he enters China, or the inhospitable regions of Central Asia, where it is difficult, if not impossible, for a European to travel alone.

"Occasionally some one escapes by way of the Amoor River, or the ports of the Okhotsk Sea; but there are not many ships entering and leaving those ports, and the police keep a sharp watch over them to make sure that they do not carry away more men than they bring. I once met in Paris a Pole who had escaped from Siberia by this route. By some means that he would not reveal to me, he managed to get out of the Amoor River and cross to the island of Saghalin. The southern half of the island was then in possession of the Japanese, and he lived among them for several months. Then he got on board an American whaling-ship, and worked his passage to San Francisco, where he found some countrymen, who helped him on his way to Paris.

TWO EXILED FRIENDS MEETING.

"I know another man, a Russian nobleman, who escaped from Siberia and went back over the route by which he had come. For convenience I will call him Ivanoff, though that was not his name. He accomplished it in this way:

"He had concealed quite a sum of money about his person, which the guards failed to find after searching him repeatedly. His offence was political, and he was sentenced to twenty years' exile. While his convoy was on the road between Krasnoyarsk and Irkutsk, he arranged to change names with Petrovitch, a criminal who had been sentenced to three years' banishment, and was to remain near Irkutsk. Ivanoff was to go beyond Lake Baikal, whence escape is much more diflicult. For one hundred roubles the criminal consented to the change, and to take his chances for the result.

"The substitution was made at the depot in Irkutsk, where the names were called off and the new convoys made out. The convoy for the trans-Baikal was first made up, and when Ivanoff's name was read the burglar stepped forward and answered the question as to Ins sentence. The officers who had accompanied them from Krasnoyarsk were not present, and so there was no great danger of the fraud heing discovered; the convoy was made up, the new officers moved off, and that was the last my friend saw of his hired substitute.

"Ivanoff (under his new name of Petrovitch) was sent to live in a village about twenty miles from Irkutsk, and required to report twice a

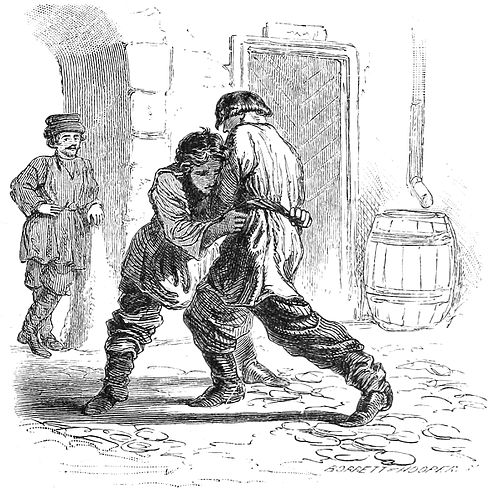

ESCAPING EXILES CROSSING A STREAM.

week to the police. He found employment with a peasant farmer and managed to communicate with a friend in much difficulty. The peasant used to send him to market with the produce of the farm, as he found that Ivanoff could obtain better prices than himself; the fact was he generally sold to his friend who purposely overpaid him, and if he did not find his fnend he added a h tie to the amount out of his own pocket. Ivanoff and his friend haggled a great deal over their transactions, and thus conversed without arousing suspicion.

"Things went on in this way for some months, and the good conduct of the apparently reformed criminal won him the favor of the police-master to whom he was required to report. His time of reporting was extended to once a week, and later to once a month. This gave him the chance of escaping.

"By a judicious use of his money he secured the silence of his employer and obtained a paderojnia of the second class. The day after

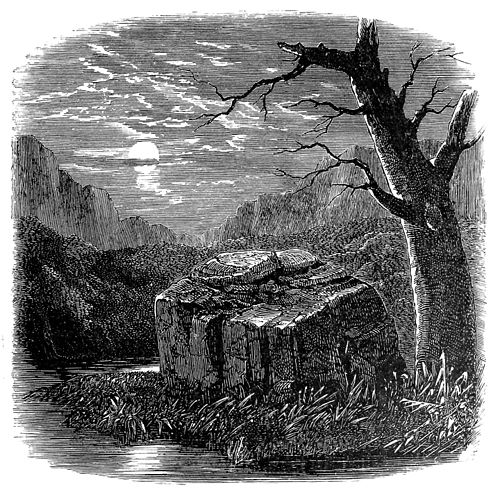

IVANOFF'S CAVE.

reporting to the police he went to fish in the Angara, the river that flows past Irkutsk and has a very swift current. As soon as he was missed his employer led the search in the direction of the river. The coat, basket, and fishing-rod of the unfortunate man lay on the bank; it was easy to see that he had been standing on a stone at the edge of the water, and the stone having given way the river had swallowed Ivanoff, and carried his body away towards the' Arctic Ocean. Some money was in the pocket of the coat, and was appropriated by the officers.

"But instead of being drowned, Ivanoff was safely concealed in a cave under a large rock in the forest. He had found it on one of his hunting excursions, and had previously conveyed to it a quantity of provisions, together with some clothing supplied by his friend in Irkutsk. There he remained for a fortnight; then he went to Irkutsk, and started on his journey.

"People leaving Irkutsk frequently drive to the first station m then own vehicles, and there hire the carriages of the posting service. So one evening Ivanoff rode out to the station in a carriage hired in front of the hotel. He did not tell me, but I suspect that his friend supplied the carriage, and possibly handled the reins himself.

"At the station he boldly exhibited his paderojnia and demanded horses, and in a few minutes he was on the road. Safe Well, he could never tell whether he was safe or not, as the telegraph might at any moment Hash an order for his detention.

"On and on he went. He pretended to be, and really was, in a great hurry. He was liberal to the drivers, but not over-liberal, lest he might be suspected. Suspicion would lead to inquiry, and inquiry would be followed by arrest. But he obtained the best speed that could be had for a careful use of money, and was compelled to be satisfied.

"Several times he thought he had been discovered, and his feelings were those of intense agony. At one of the large stations the smotretal came to him with an open telegram which said a prisoner was missing, and orders had been sent along the line to watch for him.

"Ivanoff took the telegram and read it. Then he noted down the description of the fugitive (happily not himself), and told the smotretal to take no further trouble till he heard from him, but to keep a sharp watch for all new arrivals. 'Unless I telegraph you from the next town,' said he, 'you may be sure that he has not passed any of the intervening stations.'

"He went on, and heard no more of the matter. At another point he fell in with a Russian captain going the same way as himself. The captain proposed they should travel together, for the double purpose of companionship and economy. Much as he disliked the proposal, he was forced to accede, as a refusal might rouse suspicion.

"Luckily for him, his new friend was garrulous, and did most of the talking; but, like most garrulous people, he was inquisitive, and some of

EXILES AMONG THE MOUNTAINS.

his queries were decidedly unpleasant. Ivanoff had foreseen just such a circumstance, and made up a plausible story. He had just come to Siberia, and only three days after his arrival was summoned back by the announcement of his father's death. His presence was needed in St. Petersburg to arrange the financial affairs of the family.

"By this story he could account for knowing nobody in Siberia; and as he was well acquainted with St. Petersburg he could talk as freely as one might wish about the affairs of the capital. He was thrown into a cold perspiration at one of the stations, where his garrulous companion proposed, as a matter of whiling away the time after breakfast, that they should examine the register for the record of their journeys eastward. Ivanoff managed to put the idea out of his head, and ever after made their stay at the stations as short as possible."Imagine Ivanoff's feelings when one day the other said,

"'Exiles sometimes escape by getting forged passports and travelling on them. Wouldn't it be funny if you were one? Ha! ha! ha!'

"Of course Ivanoff laughed too, and quite as heartily. Then he retorted,

"'Now that you mentioned it, I've half a mind to take you to the next police-station and deliver you up as a fugitive. Ha! ha! ha! Suppose we do it, and have some fun with the police?"

"Thereupon the serious side of the affair developed in the mind of Mr Garrulity. He declined the fun of the thing, and soon the subject was dropped. It was occasionally referred to afterwards, and each thought how funny it would be if the other were really a fugitive.

"They continued in company until they reached Kazan. There they separated, Ivanoff going to Nijni Novgorod and Moscow, and from the latter proceeding by railway to Smolensk and Warsaw. From Warsaw he went to Vienna. As soon as he set foot on the soil of Austria he removed his hat and, for the first time in many months, inhaled a full breath of air without the feeling that the next moment might see him in the hands of the dreaded police. He was now a free man."

"And what became of his companion?"

"When they separated at Kazan, the latter announced his intention of descending the Volga to Astrachan. It was fully a year afterwards that my friend was passing a cafe in Paris, and heard his assumed name called by some one seated under the awning in front of the establishment. Turning in the direction of the voice, he saw his old acquaintance of the Siberian road.

"They embraced, and were soon sipping coffee together, Ivanoff talked freely, now that he was out of danger of discovery, and astonished his old acquaintance by his volubility. At length the latter said,

"'What a flow of language you have here in Pans, to be sure. You never talked so much in a whole day when we were together as in the hour we've sat here.'

"'Good reason for it,' answered Ivanoff. 'I had a bridle on my tongue then, and it's gone now. I was escaping from a sentence of twenty years in Siberia for political reasons.'

"'And that's what made you so taciturn,' said the other. I was escaping from the same thing, and that's what made me so garrulous When we met at that station I feared you might be on the lookou for me; and much as I hated doing so, I proposed that we should travel together.'"They had a good laugh over the circumstances of their journey, where each was in mortal terror of the other. The one was talkative and the other silent for exactly the same reason—to disarm suspicion.

"I could tell you other stories of escaping from exile, but this one is a fair sample of them all. Of those who attempt to leave the country not one in twenty ever succeeds, owing to the difficulties I have mentioned, and the watchfulness of the police. The peasants of Siberia will generally help an escaping exile, but they do not dare to do it openly. Many of them put loaves of bread outside their windows at night, so that the runaways can come and obtain food without being seen. They plant little patches of turnips near the villages for the same reason, and call them gifts to the 'unfortunates.' Whenever the soldiers find any of these turnip-patches they destroy them, in order to hinder the progress of fugitives.

"There is said to be a secret road or path through Siberia known only to the exiles; it is about two thousand miles long, avoids all the regular lines of travel, and keeps away from the towns and villages. It winds over plains and among the mountains, through forests and near the rivers, and is marked by little mounds of earth, and by notches cut in the trees.

"Those who travel this road must undergo great hardship, and it is said that not more than half who undertake it are ever heard of again. They perish of starvation or cold, or may venture too near the villages in search of food, and fall into the hands of the police. The path must be travelled on foot, as it is not sufficiently broad for horses; and when any part of it is discovered by the soldiers the route must be changed. The exiles have means of communicating with each other, and no matter how closely the authorities may watch them, an occurrence in one Siberian prison will soon be known at all others in the country."

Frank asked Mr. Hegeman if he had ever seen any prisoners in Siberia wearing chains?

"Many of them," was the reply, "especially in the prisons in the towns, and at the places where they are kept at hard labor. The simple exiles are not required to wear chains; it is only those condemned to hard

labor for a long term of years that are thus oppressed. By an old law of Russia the chains must not weigh more than five pounds; there is a belt around the waist, and from this belt a chain extends to an iron band around each ankle. The clanking of the chains, either on the road or in the prisons, has a most horrible sound.

"The continued use of this relic of barbarism is strenuously opposed by a great many Russians. With the exception of the 'ball and chain,' which is a form of military punishment everywhere, no other Christian nation now requires its prisoners to wear chains continually. If the Emperor of Russia would issue a decree that henceforth no prisoner shall be put in chains except for specially unruly conduct or other good cause, and

SIBERIA IN SUMMER.

abolish altogether the present regulations about chains, he would take a long advance step for his nation."

Doctor Bronson and the youths agreed with him. Fred was about to ask a question when one of the stewards made the announcement, "Obed gotovey, gospoda!" ("Dinner is ready, gentlemen!")

Siberia and its exiles were forgotten for the time, as the party adjourned to the dining-saloon of the steamer.