The Boy Travellers in the Russian Empire/Chapter 17

CHAPTER XVII.

WHEN the conversation about Siberia was resumed, Frank suggested that there must be a great many people in that country who were descended from exiles, since it had been for a long time a place of banishment, and the exiles were accompanied in many cases by their families.

"Your supposition is correct," said Mr. Hegeman; "the descendants of exiles are probably more numerous to-day than are the exiles themselves. Eastern Siberia is mainly peopled by them, and Western Siberia very largely so. All serfs exiled to Siberia under the system prevailing before the emancipation became free peasants, and could not be restored to their former condition of servitude.

"Many descendants of exiles have become wealthy through commerce or gold-mining, and occupy positions which they never could have obtained in European Russia. When I visited Irkutsk I made the acquaintance of a merchant whose fortune ran somewhere in the millions. He had a large house, with a whole retinue of servants, and lived very expensively. He was the son of an exiled serf, and made his fortune in the tea-trade.

"Many prominent merchants and gold-miners were mentioned as examples of the prosperity of the second and third generations from exiles. Of those who had made their own fortunes in the country the instances were by no means few. One, an old man, who was said to have a large fortune and a charming family of well-educated children, was pointed out as an illustration of the benefits of exile. Forty years before that time he was sent to Siberia by his master out of the merest caprice. In Siberia he obtained fortune and social position. Had he remained in Europe he would probably have continued a simple peasant, and reared his children in ignorance."The advantages of Siberia are further shown by the fact that a great many exiles, decline to return to European Russia after their terms of service are ended. Especially is this the case with those who are doing well financially, or have families with them, either from their old tomes

AN EXILE PEASANT AND HIS FRIENDS.

Fred asked if they had the same system of serfdom in Siberia before the emancipation as in European Russia.

"At the time of the emancipation," said Mr. Hegeman, "there was only one proprietor of serfs in all Siberia; he was the grandson of a gentleman who received a grant of land, with serfs, from Catherine II. None of the family, with a single exception, ever attempted to exercise more than nominal authority, and that one was murdered in consequence of enforcing his full proprietary rights.

"Siberia was a land of freedom, so far as serfs were concerned. The system of serfdom never had any foothold there. The Siberians say that

the superior prosperity enjoyed by the peasants of their part of Russia had a great deal to do with the emancipation measures of Alexander II. The Siberian peasants were noticeably better fed, clothed, and educated than the corresponding class in European Russia, and the absence of masters gave them an air of independence. Distinctions were much less marked among the people, and in many instances the officials associated familiarly with men they would have hesitated to recognize on the other side of the Ural Mountains."

"It sounds odd enough to talk about Siberia as a land of freedom," said Fred, "when we've always been accustomed to associate the name of the country with imprisonment."

Just then the steamer stopped at one of its regular landings; and as she was to be there for an hour or more, the party took a stroll on shore. There were only two or three houses at the landing-place, the town which it supplied lying a little back from the river, upon ground higher than the bank.

It happened to be a holiday, and there was quite a group at the landing-place. The peasants were in their best clothes, and several games were in progress. Frank and Fred hardly knew which way to turn, as there were several things they wished to see all at once.

Some girls were in a circle, with their hands joined; they were singing songs which had a good deal of melody, and the whole performance

reminded the youths of the "round-a-ring-a-rosy" game of their native land. Close by this group were two girls playing a game which was called skakiet in Russian. They had a board balanced on its centre, and a girl stood on each end of the board. The maidens jumped alternately into the air, and the descent of one caused her companion to go higher each time. Mr. Hegeman said it was a favorite amusement in the Russian villages. It required a little practice, as the successful performer must maintain a perfectly upright position. Two girls who are skilled at the game will sometimes keep up this motion for fifteen or twenty minutes without apparent fatigue.

Among the men there were wrestling-matches, which were conducted with a good deal of vigor. Frank observed that some of the wrestlers received very ugly falls, but did not seem to mind them in the least. The Russian peasantry are capable of rough handling. They are accustomed to it all their lives, and not at all disturbed by anything of an ordinary character. They resemble the lower classes of the English populace more than any other people.

The women are more refined than the men in their amusements. Ringing and dancing are very popular among them, and they have quite a variety of dances. A favorite dance is in couples, where they spin round and round, until one of the pair drops or sits down from sheer fatigue.

As our friends strolled near the river-bank they came upon a group of

women engaged in one of these dances. Three or four of the by-standers were singing, and thus supplied the music; two women stood facing each other in the centre of the group, each with her hands resting on her hips. One of the singers raised her hands, and at this signal the whirling began.

When this couple was tired out another came forward, and so the dance was kept up. Fred thought the dress of the dancers was not particularly graceful, as each woman wore stout boots instead of shoes. They had already observed that the old-fashioned boot is not by any means confined to the sterner sex among the Russian peasantry.

Some of the women wore flowers in their hair, but the majority of the heads were covered with handkerchiefs. Doctor Bronson explained to the youths that a woman may wear her hair loosely while she is unmarried, but when she becomes a wife she wraps it in a kerchief, or encloses it in a net.

Naturally this explanation by the Doctor led to a question about marriage customs in Russia.

"Courtship in Russia is not like the same business in America," remarked the Doctor, in reply to the query. "A good deal of it has to be done by proxy."

"How is that?"

"When a young fellow wishes to take a wife, he looks around among the young women of his village and selects the one that best pleases him. Then he sends a messenger—his mother, or some other woman of middle age—to the parents of the girl, with authority to begin negotiations. If they can agree upon the terms of the proposed marriage, the amount of dowry the bride is to receive, and other matters bearing on the subject, the swain receives a favorable report. Sometimes the parents of the girl are opposed to the match, and will not listen to any proposals; in such case the affair ends at once, the girl herself having nothing to say in the matter. Quite likely she may never know anything about it.

"The whole business is arranged between the elders who have it in charge. The custom seems to be largely Oriental in its character, though partaking somewhat of the marriage ways of France and other European countries.

"Supposing the negotiations to have resulted favorably, the young man is notified when he can begin his visits to the house of his beloved. He dresses in his best clothes (very much as an American youth would do under similar circumstances), and calls at the appointed time. He carries a present of some kind—and the long-established custom requires that he must never make a call during his courtship without bringing a present. One of the gifts must be a shawl."

"In that case," said Fred, "the young men are probably favorable to short courtships, while the girls would be in no hurry. If every visit must bring a present, a long courtship would heap up a fine lot of gifts."

"That is quite true," Doctor Bronson replied, "and instances have been known where the match was broken off after the patience and pocket of the suitor were exhausted. But he has a right to demand a return of his presents in such an event."

"And, as has happened in similar cases in America," Frank retorted, "he does not always get them."

"Quite true," said the Doctor, with a smile; "but the family playing such a trick would not find other suitors very speedily. Human nature is the same in all countries, and even the young man in love is shy of being defrauded.

"But we will suppose everything has gone favorably," the Doctor continued, "and the suitor has been accepted. As a matter of fact, Russian

courtships are short, only a month or two, and possibly for the reason you suggested. A day is fixed for the betrothal, and the ceremony takes place in the presence of the families of both the parties to the engagement. The betrothal is virtually a marriage ceremony, as it binds the two so firmly together that only the most serious reasons can separate them. The betrothal ceremony is at the house of the bride's parents, and is followed in due course by the wedding, which takes place in church.

"Custom requires that the bride shall supply a certain quantity of linen and other household property, while the husband provides the dwelling and certain specified articles of furniture. Between them they should be able to set up house-keeping immediately, but there are probably many cases where they cannot do so. Among well-to-do people the bride provides a dozen shirts, a dressing-gown, and a pair of slippers for her husband; she is supposed to spin the flax, weave it into cloth, and make the shirts; but, as a matter of fact, she buys the material, and very often gets the garments ready-made.

"For a day or two before the wedding, all the dowry of the bride is exhibited in a room set apart for the purpose; a priest blesses it with holy water, and friends call to gaze upon the matrimonial trophies. Among the middle and upper classes the bridegroom gives a dinner to his bachelor friends, as in some other countries, the evening before the wedding; the bride on the same evening assembles her companions, who join in singing farewell to her. The bridegroom sends them a liberal supply of candy, cakes, bonbons, and the like, and they indulge in quite a festivity.

"Among the peasants the companions of the bride accompany her to the bath on the evening before the wedding, and both going and returning she is expected to weep bitterly and loudly. An English lady tells how she heard a Russian girl, who was about to be married, giving vent to the wildest grief, while her companions were trying to cheer her by singing. The lady felt very sorry for the poor maiden, and rejoiced when she passed out of hearing.

"A little later in the evening the lady went with a friend to call at the bride's cottage, and entered quite unannounced. The bride was supping heartily, her face full of expressions of joy; the Englishwoman was startled and still more surprised when the girl asked,

"'Didn't I do it well?'

"It then came out that the weeping was all a farce, though there may be cases where it is not so.

"On the day of the wedding the bride and groom do not see each other until they meet in church. After the ceremony the whole party goes to the house of the bride's parents, where a reception is held in honor of the event. When it is over, the young couple go to their own home, if they have one; the next morning all the parents and relatives go and take coffee with the newly married; then there are dinner-parties at the houses of both pairs of parents; other parties and dinners follow, and sometimes the feasting is kept up for a week or more. It is a trying ordeal for all concerned, and there is general rejoicing when the festivities are over.

"Among the peasantry it is the custom, at least in some parts of Russia for the bride to present a whip to her husband the day after the wedding. This whip is hung at the head of the bed, and, if report is true, it is not unfrequently used."

"I remember seeing a whip hanging at the head of the bed in some of the houses we have visited," said Fred, "and wondered what it was there fo.r"

"The curious thing about the matter is," the Doctor continued, "that, a good many wives expect the whip to be used. The same lady I just

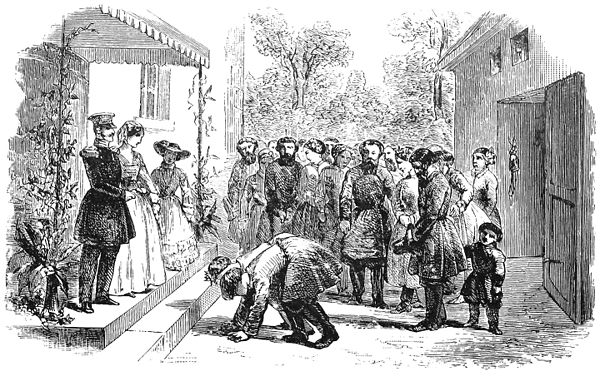

MAKING CALLS AFTER A WEDDING.

referred to says that one of her nurse-maids left her to be married A short time after the marriage she went to the nachalnik, or justice of the peace, of her village, and complained that her husband did not love her. The nachalnik asked how she knew it, and the young wife replied,

"'Because he has not whipped me once since we were married!'

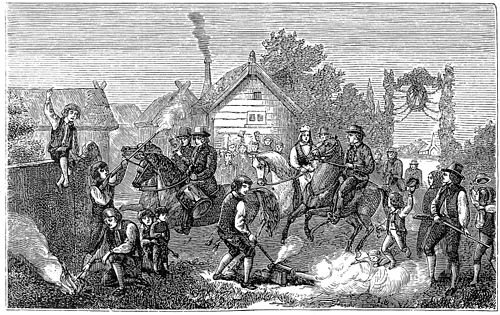

"Among the peasantry the married couple goes to the house of the owner of the estate to receive his blessing. He comes to the door and welcomes them as they bow in front of him till their foreheads nearly touch the ground."

The steamer's whistle recalled the party, and in a little while they were again on their voyage. Mr. Hegeman resumed the story of his ride through Siberia as soon as all were seated in their accustomed places.

CEREMONY AFTER A PEASANT'S WEDDING.

"Yes," replied Fred; "you had just arrived at the house of the friend of your companion, and accepted an invitation to remain for dinner."

"That was it, exactly," responded the traveller. "We had an excellent dinner, and soon after it was over we continued on our journey. We sent back the tarantasse which we had hired from the station-master, and obtained a larger and better one from our host.

"Two nights and the intervening day brought us, without any incident worth remembering, to Chetah, the capital of the province of the trans-Baikal. It is a town of four or five thousand inhabitants, and stands on the Ingodali River, a tributary of the Shilka. Below this point the river is navigable for boats and rafts, and it was here that General Mouravieff organized the expedition for the conquest of the Amoor. A considerable garrison is kept here, and the town has an important place in the history of Siberian exile. Many of the houses are large and well built. The officers of the garrison have a club, and ordinarily the society includes a good many ladies from European Russia.

"I stopped two or three days at Chetah, and my courier friend continued his journey. Finding a young officer who was going to Kiachta, on the frontier of Mongolia, I arranged to accompany him, and one evening we started. I think I have before told you that a Siberian journey nearly always begins in the evening, and is continued day and night till its close. The day is passed in making calls, and usually winds up with a dinner at somebody's house. After dinner, and generally pretty late in the evening, the last call is made, the last farewells are spoken, and you bundle into your vehicle and are off.

"From Chetah the road steadily climbed the hills, and my companion said we would soon be over the ridge of the Yablonnoi Mountains, and in the basin of the Arctic Ocean. From the eastern slope of the mountains the rivers flow through the Amoor to the Pacific Ocean; from the western slope they run into Lake Baikal, and thence through the outlet of that lake to the great frozen sea that surrounds the pole. The cold rapidly increased, and when we crossed the ridge it seemed that the thermometer went ten decrees lower in almost as many minutes.

"The country through which we passed was flat or slightly undulating, with occasional stretches of hills of no great height. There are few Russian villages, the principal inhabitants being Bouriats, a people of Mongol origin, who are said to have been conquered by the hordes of Genghis Khan five hundred years ago. They made considerable resistance to the

THE MOUNTAINS NEAR CHETAH.

Russians when the latter came to occupy the country, but ever since their subjugation they have been entirely peaceful.

"Some of the Bouriats live in houses like those of the Russians, but the most of them cling to the yourt or kibitka, which is the peculiar habitation of the nomad tribes of Central Asia. Even when settled in villages they prefer the yourt to the house, though the latter is far more comfortable than the former.

"We changed horses in a Bouriat village, where a single Russian lived and filled the office of station-master, justice of the peace, governor, secretary, and garrison. I took the opportunity of visiting a yourt, which proved to be a circular tent about eighteen feet in diameter, and rounded at the top like a dome. There was a frame of light trellis-work covered with thick felt made from horse-hair; at the highest point of the dome the yourt has an open space which allows the smoke to pass out, at least in theory. A small fire is kept burning in the middle of the floor during the day, and covered up at night; the door is made of a piece of felt of double or treble thickness, and hanging like a curtain over the entrance.

"I had not been two minutes inside the yourt before my eyes began to smart severely, and I wanted to get into the open air. The pain was caused by the smoke, which was everywhere through the interior of the tent, but did not seem to inconvenience the Bouriats in the least. I noticed, however, that nearly all their eyes were red, and apparently inflamed, and doubtless this condition was caused by the smoke.

"A family of several persons finds plenty of space in one of these tents, as they can be very closely packed. The furniture is principally mats and skins, which are seats by day and beds by night. They have pots and kettles for cooking, a few jars and bottles for holding liquids, sacks for grain, half a dozen pieces of crockery, and little else. A wooden

box contains the valuable clothing of the family, and this box, with two or three bags and bundles, forms the entire wardrobe accommodation.

"My attention was drawn to a small altar on which were tiny cups containing oil, grain, and other offerings to the Deities. The Bouriats are Buddhists, and have their lamas to give them the needed spiritual advice. The lamas are numerous, and frequently engage in the same callings as their followers. By the rules of their religion they are not permitted to kill anything, however small or insignificant. Whenever a lama has a sheep to slaughter he gets everything ready, and then passes the knife to his secular neighbor.

"The Bouriats are not inclined to agriculture, but devote most of their energy to sheep-raising. They have large flocks, and sell considerable wool to the Russians. Their dress is a mixture of Russian and Chinese, the conveniences of each being adopted, and the inconveniences rejected. They decorate their waist-belts with steel or brass, shave the head, and wear the hair in a queue, but are not careful to keep it closely trimmed. With their trousers of Chinese cut, and sheepskin coats of Russian model, they presented an odd appearance. The women are not generally good-looking, but there is now and then a girl whose face is really beautiful.

"We were called from the yourt with the announcement 'Loshadi gotovey' ("Horses are ready"), and were soon dashing away from the village. Our driver was a Bouriat; he handled the reins with skill and the whip with vigor, and in every way was the equal of his Russian competitor. For two or three hundred miles most of our drivers were Bouriats, and certainly they deserve praise for their equestrian abilities. At many of our stopping-places the station-masters were the only Russians, all the employés being Bouriats."

Frank asked whether the Bouriats had adopted any of the Russian manners and customs, or if they still adhered to their Mongol ways.

"They stick to their customs very tenaciously," was the reply, "and as for their religion, the Russian priests have made no progress in converting them to the faith of the Empire. Two English missionaries lived for many years at Selenginsk, which is in the centre of the Bouriat country, and though they labored earnestly they never gained a single convert.

"Buddhism is of comparatively recent origin among these people. Two hundred years ago they were Shamans, or worshippers of good and evil spirits, principally the latter, and in this respect differed little from the wild tribes of the Amoor and of Northern Siberia. About the end of the seventeenth century the Bouriats sent a mission to Lassa, the religious capital of Thibet, and a stronghold of Buddhism. The members of this mission were appointed lamas, and brought back the paraphernalia and ritual of the new faith; they announced it to the people, and in an astonishingly short time the whole tribe was converted, and has remained firm ever since.

"We spent a day at Verckne Udinsk, which has a church nearly two hundred years old, and built with immensely thick walls to resist the earthquakes which are not uncommon there. In fact there was an earthquake shock while we were on the road, but the motion of the carriage prevented our feeling it. We only knew what had happened when we reached the station and found the master and his employés in a state of alarm.

"The Gostinna Dvor contained a curious mixture of Russians and Bouriats in about equal numbers, but there was nothing remarkable in the goods offered for sale. An interesting building was the jail, which seemed unnecessarily large for the population of the place. A gentleman who knew my companion told us that the jail was rapidly filling up for winter. 'We have,' said he, a great number of what you call tramps in America; in summer they wander through the country, and live by begging and stealing, but in winter they come to the jails to be lodged and fed until warm weather comes again. After spending the cold season here they leave in the spring—as the trees do.'

"He further told us there was then in the jail and awaiting trial a man who confessed to the murder of no less than seventeen people. He had been a robber, and when in danger of discovery had not hesitated to kill those whom he plundered. On one occasion he had killed four persons in a single family, leaving only a child too young to testify against him."

Fred wished to know if robberies were common in Siberia.

"Less so than you might suppose," was the reply, "when there is such a proportion of criminals among the population. They are mostly committed in summer, as that is the season when the tramps are in motion. The principal victims are merchants, who often carry money in large amounts; officers are rarely attacked, as they usually have only the money needed for their travelling expenses, and are more likely than the merchants to be provided with fire-arms and skilled in their use. My companion and myself each had a revolver, and kept it where it could be conveniently seized in case of trouble. We never had any occasion to use our weapons, and I will say here that not once in all my journey through Siberia was I molested by highwaymen.

"When we left Verckne IJdinsk we crossed the Selenga, a river which rises in Chinese Tartary, and after a long and tortuous course falls into Lake Baikal, whence its waters reach the Arctic Ocean. There was no

bridge, and we traversed the stream on a ferry. The river was full of floating ice, and the huge cakes ground very unpleasantly against the sides of the craft which bore ourselves and our tarantasse. The river was on the point of freezing; there was just a possibility that it would close while we were crossing, and keep us imprisoned until such time as the ice was thick enough to bear us safely. As this would involve a detention of several hours where the accommodations were wretched, the outlook was not at all pleasant.

"All's well that ends well; we landed on a sand-bank on the other side, and after a little delay the boatmen succeeded in getting our carriage on shore without accident. About six miles from the river the road divided, one branch going to Irkutsk and the other to Kiachta, our destination. Away we sped up the valley of the Selenga. The road was not the best in the world, and we were shaken a good deal as the drivers urged their teams furiously.

"On this road we met long trains of carts laden with tea. Each cart has a load of from six to ten chests, according to the condition of the roads, and is drawn by a single horse. There is a driver to every four or five carts, and he has a bed on the top of one of his loads. The drivers were nearly always asleep, and their horses showed a good deal of intelligence in turning out whenever they heard the sound of our bells. If they did not turn out they received a reminder from the whip of our driver, who always had an extra stroke for the slumbering teamster."

Frank asked where these carts were going.

"They were going to Irkutsk," said Mr. Hegeman, "and from that city the most of the tea they carried was destined for European Russia."

"Oh, now I remember," said Frank; "Doctor Bronson told us about the tea importation from China, and how it all came overland down to 1860, with the exception of one cargo annually."

"Many persons still prefer the tea brought by land, as the herb is thought to be injured by passing over salt-water, although packed in air-tight chests. At the time I speak of, not less than a million chests of tea were taken annually from Kiachta to European Russia, a distance of four thousand miles. To Kiachta it came on the backs of camels from the tea districts of China, so that camels and horses in great number were employed in the transport of tea.

"Each chest is covered with rawhide, which protects it from rain and snow, and from the rough handling and shaking it receives. Across Siberia it is carried in carts in summer, and on sledges in winter. The horse-caravans travel sixteen hours out of every twenty-four, and the teams rarely go faster than a walk. The teams are the property of peasants, who make contracts for the work at a certain price per chest.

"For the latter part of the way the road was hilly and sandy, and our progress was slow. About nine in the evening we reached Kiachta; and as there is no hotel there, we went to the police-master to obtain lodgings."

"Not at the police-station, I hope," said Fred.

"Not at all," Mr. Hegeman responded, with a slight laugh. "In many towns of Siberia there is not sufficient travel to make hotel-keeping profitable, and consequently there are no hotels. By custom and law the inhabitants are required to receive travellers who may require accommodation, and all such lodging-places are registered with the police. For this reason we went to the police-master and received the name of the citizen who was to be honored with our company.

"It was about ten o'clock when we reached the house, accompanied by two soldiers who brought the mandate of the office and showed us the way. Everybody was in bed, and it required a good deal of knocking to rouse the servants and afterwards the master, who came to the door in his night-shirt. He stood shivering while our explanations were made,

and did not seem to realize his ludicrous appearance until we were admitted to the mansion and our baggage was landed."

Frank inquired if it was often necessary in Siberian towns to obtain lodgings in this way, and whether they were paid for?

"It was only the lateness of the hour and the fact that neither of us had ever been in Kiachta that compelled us to apply to the police-master. Travellers are unfrequent in Siberia, and the few strangers that go through the country are cordially welcomed. Officers are entertained by their fellow-officers, and merchants by their fellow-merchants. Lodgings obtained as we obtained ours are paid for exactly as they would be at a hotel. We were invited to move the next day, but were so well lodged that we chose to stay where we were.

"The morning after our arrival we delivered our letters of introduction and made numerous calls, the latter including a visit to the Sargootchay, or Chinese Governor of Mai-mai-chin. Which of you has read enough about the relations between China and Russia to tell me about these two places—Kiachta and Mai-inai-chin?"

Frank was the first to speak, which he did as follows:

"Kiachta and Mai-mai-chin were built in 1727 for the purposes of commerce—Mai-mai-chin meaning in Chinese 'place of trade.' The towns are about a hundred yards apart, one thoroughly Russian and the other as thoroughly Chinese. From 1727 to 1860 nearly all the trade between the two empires was conducted at this point, and the merchants who managed the business made great fortunes. Women were forbidden to live in Mai-mai-chin, and down to the present day the Chinese merchants keep their families at Urga, two or three hundred miles to the south. The same

CHINESE CASH FROM MAI-MAI-CHIN.

restriction was at first made upon the Russian merchants at Kiachta, but after a time the rule was relaxed and has never since been enforced. Until quite recently, strangers were forbidden to stay over-night in Kiachta, but were lodged at Troitskosavsk, about two miles away."

"I should say right here," remarked Mr. Hegeman, "that my friend and myself were really lodged in Troitskosavsk and not in Kiachta. The latter place had about a thousand inhabitants, and the former four or five thousand. At a distance only Kiachta is mentioned, just as a man may say he lives in London or New York when his home is really in a suburb of one of those cities."

"I have read somewhere," said Fred, "that the Russian and Chinese Governments stipulated in their treaty that the products and manufactures of each country should be exchanged for those of the other, and no money was to be used in their commercial transactions."

"That was the stipulation," said Doctor Bronson, "but the merchants soon found a way to evade it."

"How was that?"

"The balance of trade was greatly in favor of China, as the Russians wanted great quantities of tea, while they did not produce or manufacture

ARTICLES OF RUSSIAN MANUFACTURE.

many things that the Chinese could use. Furs were the principal articles of Russian production that the Chinese would take, but their demand for them was not enough to meet the Russian demand for tea. The treaty forbade the use of gold or silver coin under severe penalties, but somebody discovered that it did not prohibit articles of Russian manufacture being made of those metals. So they used to melt gold and silver coin, and cast them into Chinese idols which were sold by weight. The Government prohibited the melting of its coin, and then the merchants bought their crude gold and silver directly from the miners. With this source of supply always at hand they were able to supply 'articles of Russian manufacture' without difficulty. As late as 1860 every visitor to Kiachta was searched, to make sure that he had no gold coin in his possession."