Wood Carvings in English Churches II/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II

POSITION, NUMBER AND ARRANGEMENT OF STALLS

The history of the changes of position of the stalls of the clergy is one of the most curious and least understood episodes in ecclesiology; it may be worth while therefore to go into it somewhat at length, and to begin at the beginning. As regards what was at all times the main service in the church, the Mass, there were two conditions which it was desirable to bear in mind in church planning. One was that the celebrant should face to the East; the other that the congregation should face to the East. In the earliest Christian days the latter was most often disregarded. The earliest arrangement, normally, of a Christian church was that the sanctuary, containing the altar, should be to the west, and that the laity should be in the nave occupying the eastern portion of the church. At this time the western portion of the church consisted of a semicircular apse. This apse had a double function. On the chord of it was placed the High altar (in the earliest days it was the only altar); and to the west of it stood the celebrant facing east and facing the congregation, as he does to this day at St Ambrogio, Milan, and other churches which retain this primitive plan. Behind the altar, ranged round the apse, were the seats of the clergy, having in the centre the throne of the bishop. Thus the apse, like the chancel of an English parish church, had a double function; the portion containing the altar was the sanctuary, the portion containing the seats of the bishop and his presbyters was the choir; basilicas so orientated were divided into nave, sanctuary, choir; whereas English parish churches divide into nave, choir, sanctuary. Many examples of basilicas with eastern nave and western choir still survive in Rome, Dalmatia, and Istria. To this day in Milan cathedral and St Mark's, Venice, the stalls of the clergy and singers are placed on either side of and at the back of the high altar; the apse, with infinite loss to the dignity of the services, being made to serve both as sanctuary and choir.

Lincoln

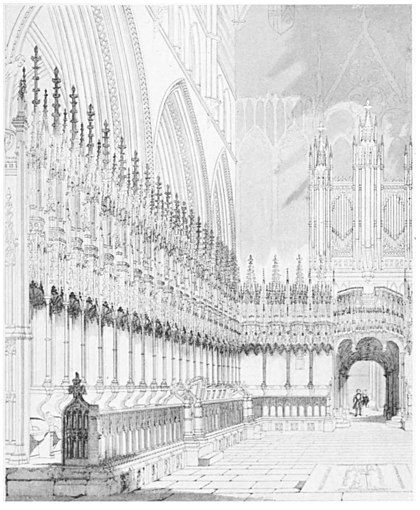

York Minster

There is, however, an alternative plan, which may have been in use from the first simultaneously with the other. At any rate it can be but little later, for in 386 was begun the important church of St Paul extra muros at Rome, with apse to the east and nave to the west. By this alteration, if no further change had been made, the congregation would face eastward, but the celebrant and the bishop with his presbyters westward. Strangely enough, this curious arrangement was actually adopted at least once in England. In the walling of the semicircle of the cathedral apse at Norwich there still remains the bishop's throne and portions of the seats of his clergy. And since Norwich cathedral is not orientated to the west, but to the east, it follows that the people faced east and the bishop and clergy west; it is hardly conceivable, however, that the celebrant can have faced west. Such a disposition can never have been but rare. A new arrangement was made; in the first place the celebrant was made to face eastward, with his back to the congregation, thus permanently obscuring their view of the altar and of many portions of the office; in spite of its obvious and great disadvantages this position has been retained in the vast majority of Western churches ever since. There remained the question of the seating of the bishop and presbyters. The remedy adopted was to transfer them from the apse to the nave; the result being that they sat to the west instead of to the east of the altar. In this second position for some considerable time the seats of the clergy remained. At S. Clemente, S. Maria in Cosmedin,[1] and other basilican churches in Rome, the seats of the clergy still remain in the eastern bays of the nave, separated off, however, all round by low marble screens, which, at S. Clemente, are mainly those of the sixth century church.

Great was the revolution wrought in church planning by the determination that the laity, clergy, and celebrant should all alike face East. To the Catholic believer nothing was of more mystic import than the orientation of the church. He prayed toward the East, toward the Holy Land where his Lord lived and died and was buried; he looked forward to the dawn of that day when He should come from the East to judge the quick and dead.

"Our life lies eastward; every day

Some little of that mystic way

By trembling feet is trod;

In thoughtful fast and quiet feast

Our heart goes travelling to the East

To the incarnate God;

Still doth it eastward turn in prayer

And rear its saving altar there;

Still doth it eastward turn in creed,

While faith in awe each gracious deed

Of her dear Saviour's love doth plead;

Still doth it turn at every line

To the fair East, in sweet mute sign

That through our weary strife and pain

We crave our Eden back again."[2]

The next step appears first in ninth century churches, and in the plan of the monastery of St Gall. It involved no change in the position of the stalls of the clergy; but instead of being placed in the eastern bays of the nave, the sanctuary was lengthened to contain them. And so we reach the familiar parochial chancel, with its western portion forming a choir, and its eastern a sanctuary. The clergy left the nave and the laity in the midst of whom they had so long sung and prayed, and removed to the chancel, where to the north and south were solid walls, while to the west, no doubt very shortly, was added a screen guarding the entrance to the chapel. Though the new plan made no alteration in the relative position of the stalls of the clergy, it was nevertheless a real revolution. The chancel became practically a secluded, closed chapel; the offices and services which had been performed in the midst of the laity became more and more the prerogative of a privileged ecclesiastical order; in the end, in the greater churches, special altars were put up for the laity in the nave; except in the parish churches, laymen lost the right to participate in services at the High Altar.

Carlisle

In our great monastic and collegiate churches it was long before the ninth century innovation—viz., the insertion of the choir in the eastern limb of the church—was generally adopted; in some it was never adopted at all. The typical Cistercian churches, e.g., Kirkstall, reverted to the Early Christian arrangement, by which the eastern division of the church was appropriated exclusively to the sanctuary; and this was the case with many Benedictine and collegiate churches also. Till ignorant and incompetent "restorers" were let loose on them, the eastern limb of the cathedrals of the Secular Canons of Wells and Hereford, that of the Benedictine cathedral of Ely and others formed one vast sanctuary, the stalls being placed under the central tower and in the eastern part of the nave; at Wells the choir had a length of 47 feet, but the sanctuary of 67 feet. The reason why a sanctuary so long was required was no doubt that it was desired to place in it two altars; one, the "choir" or "matins" altar, for ordinary services; the other, the High altar, more to the east, reserved for High Mass.[3]

Durham

In some cases, e.g., at Westminster, in many Cistercian churches, and in Spanish cathedrals, the stalls were not placed under the central tower, but still more to the west, wholly in the nave. In Gothic days, however, in English plans—Westminster is French in plan—the tendency was more and more to place the choir of the monastic and collegiate churches in the eastern limb, just as in a parish church. In the cathedrals the precedent was first set at Canterbury, where in 1096 Prior Ernulph set out a new eastern limb consisting of an eastern apse preceded by no less than nine bays. Sometimes there was a special reason for the removal of the choir from the crossing and the nave. In several cases—in pious recollection of the burial of many a martyr in Early Christian days down in the catacombs of Rome—the Italian practice of constructing a crypt beneath the eastern limb was followed. This had been so as early as St Wilfrid, 671-678, whose crypts at Ripon and Hexham still survive, and in the Anglo-Saxon cathedrals of Winchester, Worcester, Rochester, Gloucester, Canterbury, York, and Old St Paul's. And when these were remodelled by the Norman conquerors, in all cases the crypt was reproduced. Such crypts of course necessitate the building of the eastern limb at a higher level than crossing and nave; in some cases, e.g., at Canterbury, the difference in height is very considerable. The result must have been that where as at Canterbury the sanctuary was a long one, the High altar at its east end must have been invisible, or nearly so, to monks seated in the crossing and nave. Consequently, first at Canterbury c. 1100, in the thirteenth century at Rochester, Old St Paul's and Worcester, and in the fourteenth century at Winchester and York, the stalls were removed to the eastern limb, the western portion of which now became choir. The only exception among cathedrals with crypts is Gloucester, where the crypt is low and the eastern limb is short and where the stalls remain to this day beneath the central tower. The example set by cathedrals with crypts was soon followed by churches of every degree which had none; whether Benedictine, such as at Chester, Augustinian, as at Carlisle, or served by Secular Canons, as at Exeter. And so in the churches of monks, regular canons and secular canons alike, most of the ecclesiastical authorities reverted to what had been all along the normal plan of the English parish church, viz., an eastern limb containing choir as well as presbytery.[4]

Chester

The length of the stalled choir varied of course with the number of monks or canons serving the church. In a church of the first rank, such as Lincoln or Chester, about sixty stalls seems as a rule to have been found sufficient. These would generally occupy three bays; where more than three bays are occupied with stalls, it is usually because more stalls have been added at some later period, as at Lincoln, Norwich, and Henry the Seventh's chapel, Westminster. In the centre, between the stalls, a considerable space had to be left free, in order to leave room for processions from the High Altar to the lectern and to the ecclesiastics in their stalls; as well as for processions of the whole ecclesiastical establishment on Palm Sunday, Corpus Christi day, Easter Sunday and other festivals, and on every Sunday in the year. The lectern also was often of great size, and a gangway had to be left on either side of it. In Lincoln Minster the space from one chorister's desk to the chorister's desk opposite is 18 feet: from the back of the northern to the back of the southern stalls is 40½ feet, which is above the average breadth of an English cathedral or monastic choir. The breadth of the choir conditioned the whole of the planning of the church; for as a rule the nave and transepts were naturally given the same breadth as the choir, in order that the central tower should be square.

As for the number of rows of stalls on either side of the choir, it was usually three, rising successively in height; at Lincoln the floor of the uppermost row is 2 feet 6 inches above that of the choir; the canopies rise 22 feet above the floor. At Lincoln modern additions have been made; at present the upper row consists of 62 canopied stalls; 12 of them being "return" stalls facing east; 25 facing north and 25 facing south. Below them is a row of stalls without canopies; of these lower stalls there were originally 46; in front of these again are the seats of the "children of the choir."

The number of stalls in the uppermost row was regulated in a collegiate church by the number of prebends founded in the church; in a monastic church by the number of monks in the monastery. At Westminster the number of monks between 1339 and 1538 varied from 49 to 52, 47, 30; in the upper stalls there was accommodation for 64. At Southwell there were 16 prebendaries; at times some of these were foreigners, and never visited Southwell or England; the rest stayed in their country parishes, and it was sometimes with great difficulty that a single prebendary could be got together to take charge of the Minster services; they had, however, deputies; and for them and their masters the two western bays of the present choir were probably appropriated. And for the meetings of this collegiate body, which were held seldom, and which hardly ever had an attendance of more than a half dozen prebendaries, one of the most magnificent Chapter houses in England was built. At Wells there were 54 canons or prebendaries, each with his own separate estate or prebend; the greater number of them resided on their prebendal estates in the country; only on rare occasions did they come up to Wells, and then probably only for the time occupied by some important meeting; even on such occasions there seem never to have been more than 20 canons present.[5] Nevertheless stalls were duly provided for the whole 54, and the Psalter was divided into 54 portions for daily recitation by the Bishop and his canons. Each of these absentee canons at Wells had or was expected to have a deputy in the form of a "vicar choral" who was paid by him a small stipend called "stall-wages." A beautiful street of little houses—one of the loveliest things in that loveliest of English cities—built for the vicars, still survives at Wells; others at Hereford, Lincoln, Chichester and elsewhere. At Wells the first and highest row of stalls was in practice occupied by the senior canons, the priest-vicars and deacons; the second row by junior deacons, subdeacons and others; the third row by choristers on the foundation; in front of that was a seat for choristers on probation. The seating of the choirs, however, naturally differed with the constitution of the collegiate body. Beverley Minster was not a cathedral proper; but its church and its establishment were on cathedral scale, and there are no less than 68 stalls. At Beverley the exact position in the upper row of the provost, treasurer, chancellor, clerk of the works, and other dignitaries was definitely settled in 1391 by Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of York. He directed that the clerks or vicars should occupy the lower stalls, each in front of the canon, his master; and that the choristers should sit in front of the clerks. "Clerici vero et omnes et singuli in secunda forma qui libet coram magistro suo. Pueri vero seu choristae ante clericos predictos loca sua teneant ut fieri consuevit etiam ab antiquo."[6] At the back of the canons' stalls in many churches, e.g., Chester and Norwich cathedrals (48), may still be seen painted the name of the country parish where the canon's prebend lay. Appointments to such canonries are still regularly made; but it has become usual to style the occupants "honorary canons" or "prebendaries." As a matter of fact they are just as much canons as the residentiaries. The difference is that the latter come into residence for three months a year or longer, while the former need not come at all; and if they did come, there is no house to receive them nor any stipend. How the cathedral and collegiate establishments lost, long before the Reformation, the services of the great majority of their staff cannot be told here; partly it arose from sheer neglect of duty, partly it was imposed on the canons by the necessity of serving in their parish churches and of superintending their estates.

Beverley Minster

At the backs of canons' stalls is sometimes painted the verse of a psalm. This refers to a very ancient usage. The daily recitation of the whole Psalter by the members of a cathedral chapter, according to the psalms attached to their respective prebends, formed part, in the opinion of Mr Henry Bradshaw, of the Consuetudines introduced by the Norman bishops in the twelfth century. In the Liber Niger or Consuetudinary of Lincoln Minster, copies of which, earlier than 1383, remain in the Muniment Room, it is stated that "it is an ancient usage of the church of Lincoln to say one mass and the whole psalter daily on behalf of the living and deceased benefactors of the church." At Wells also the whole Psalter was recited daily for the same pious purpose. At Lincoln tablets still are to be seen on the backs of the stalls giving the initial verse in Latin of the psalms which the holder of the prebend is bound to recite daily: and at the installation of each prebendary, the Dean calls his attention to the tablet and admonishes him not to discontinue the obligation (52). Even at St Paul's, though the original stalls all perished in the fire of 1666, fifteen of the present stalls on each side are inscribed with the Latin words with which various psalms commence; the Psalter here being divided into thirty portions.

- ↑ Illustrated in the writer's Screens and Galleries, 2.

- ↑ Faber's Poems, pp. 227-229.

- ↑ See the writer's Westminster Abbey, 48.

- ↑ For plans of St Gall, Kirkstall, Westminster, Canterbury, Exeter, York, see the writer's Gothic Architecture in England.

- ↑ For an account of the working of the system of Secular Canons in the English cathedrals see Canon Church's paper in Archæologia, lv.; Professor Freeman's Cathedral Church of Wells; Mr A. F. Leach on Beverley Minster in vols. 98 and 100 of the Surtees Society, and on Southwell Minster in the 1891 volume of the Camden Society; and Rev. J. T. Fowler, D.C.L., on Ripon Minster in vols. 64, 74, 78, 81 of the Surtees Society.

- ↑ See Mr A. F. Leach's Memorials of Beverley Minster, Surtees Society, vols. 98 and 108.