Wood Carvings in English Churches II/Chapter 4

CHAPTER IV

TABERNACLED STALLS

In the latter years of the fourteenth century we come to a new form of stall design; one in which the English carvers won their greatest triumphs, and which became the standard and typical design for English stalls. It is seen in the magnificent tabernacled stalls of Lincoln, Chester, Nantwich, Carlisle, Windsor, St Asaph, Ripon, Manchester, Westminster, Beverley and Durham. To distinguish this group, we may term it "stallwork with tabernacled canopies," or, more shortly, "tabernacled stalls." Though new, it is, like all design, based on earlier models. At Ely (37) two distinct and conflicting designs are combined; to those two the Lincoln carvers gave unity (17). The stallwork at Ely is in two stories; but they are not correlated in any way. The upper story consists of canopied niches, now containing figures, formerly probably occupied by paintings. At Lincoln the lower story was omitted, reducing the elevation to a single story; while the niches of the Ely upper story were brought low down, and made to enshrine the vested canons below. The Lincoln niches, however, are of more elaboration than those of Ely; in the latter each niche was fronted by three straight-sided pediments; in the former the pediments are hollow-sided, and in front of each is a bowing ogee arch. Then these niches are repeated above, except that each niche is single instead of being triple, and enshrines a statuette of wood, and is flanked by window tracery. Moreover, above each upper niche, as at Ely, rises a lofty spirelet with crockets and finials, encircled by a coronal of ogee gables and flanked by tall slender pinnacles, themselves also ornamented with miniature niches, crockets and finials. Also the upper portions of the shafts below are niched, crocketed and battlemented. Thus the Ely design becomes thoroughly harmonious and at one with itself.

Lincoln

Chester

As a rule, design did not originate with the wood carver; it first found expression in stone. And it well may be that to earlier work executed in stone rather than to the stallwork of Ely the Lincoln design is to be attributed. At any rate, the tabernacled canopies of wood are anticipated in most marked fashion in the monument of Archbishop Stratford in Canterbury cathedral. He died in 1348; his monument is therefore earlier than any of the tabernacled canopies in wood. It consists of two stories, with three gables below and a single niche above; then come spirelets with pinnacles between.[1] There is a similar monument to Archbishop Kemp, who died in 1454. Of the Lincoln work Mr A. W. Pugin said that "the stalls are executed in the most perfect manner, not only as regards variety and beauty of ornamental design, but in accuracy of workmanship, which is frequently deficient in ancient examples of woodwork.... They are certainly superior to any other choir fittings of that period remaining in England. The misericords also are all varied in design, and consist of foliage, animals, figures and even historical subjects, beautifully designed, and executed with surpassing skill and freedom." As the work was begun by the treasurer, John of Welbourn, who died in 1380, we may give it the approximate date of 1370. This is borne out by the fact that on the base of the Dean's stall are the bearings of Dean Stretchley, who died in 1376.[2]

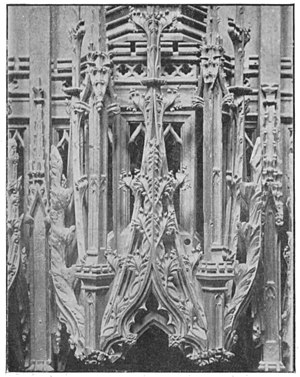

Judging from the armour represented on the misericords the design of the Lincoln stalls was copied very soon afterwards, say c. 1390, in Chester cathedral, but with a magnificence of foliated ornament which is reminiscent of the glorious stalls of Lancaster. For the main lines of the design, however, the new type of canopy which had been worked out at Lincoln was taken as a model; the details only are those of Lancaster, the general design is from Lincoln. As at Lincoln, the lower canopy has duplicated gables in front of each of the three faces of the main structure of the canopy. This main structure starts from between pinnacled buttresses, as it were, separating each canopy; then is brought forward like an oriel window, having square-headed traceried windows, the whole surmounted by a battlemented pierced parapet. In front of each face of the oriel is first a truncated ogee arch, and second, a complete ogee arch, both springing from a battlemented and pinnacled corner buttress. These buttresses, whether between the canopies or in front of the corners of the oriels, are truncated, the former rising not from the shoulders of the stalls below but from angels, the latter from carved bosses or paterae. The gables at the back spring from a higher level than those in front, and, as at Lincoln, are truncated ogee arches. The three front gables are complete ogee arches, which differ from those in the Lincoln stallwork in that their lower convex curve spreads outward again. This is an important matter; for though this compound ogee arch is not employed in the Lincoln stalls, yet it occurs up and down the cathedral in the stonework of the fourteenth century; e.g., in the arcading under the western towers[3] put up by the same treasurer who paid for the stalls. It is so special and characteristic to Lincoln that its presence at Chester may be taken as a decisive proof of Lincoln influence in the design of the stalls. In the upper story is a central niche, flanked by window tracery, as at Lincoln. Above rises a lofty spirelet, encircled at its base by "Lincoln ogee" gables. Between the spirelets, as at Ely and Lincoln, are tall pinnacles. The leafage of the lower canopies should be compared with that of Lancaster. In the five examples illustrated (53, 55, 56) it will be seen how consummate and versatile in design were these mediæval craftsmen; they were bubbling over with design, and could not repeat themselves if they wished.[4]

Chester |

Chester |

Chester |

Chester |

Nantwich |

Nantwich |

The magnificent church of Nantwich, Cheshire, was in building before the Black Death of 1349; the work was then stopped; and when it was resumed, it was carried out in a different style. To this later period belong the south transept and the east window of the chancel with rectilinear tracery; it is probable that the pulpit and stalls also belong to this second work, c. 1400. The design connects itself with that of the Lincoln and Chester stalls in the absence of any line of demarcation between the upper and lower portions; but while that of Chester is reminiscent of early fourteenth century work, that of Nantwich is well advanced toward normal fifteenth century design. It is also much richer than either, the lower stage being a mass of niches and pinnacles, with angel corbels below. The great novelty at Nantwich is the absence of spirelets, the absence of which is nobly compensated for by the increased height and prominence given to the central of the three upper niches (57).

York Minster

The stalls of York Minster were destroyed by fire in 1819. Both in the treatment of the supporting shafts and in the design of the single upper niches flanked by window tracery they closely resembled the Lincoln stalls, on which they were probably modelled; above the upper niches rose spirelets flanked by pinnacles. There is a marked horizontal line midway, dividing the composition into two stories (58). The presbytery of York Minster was built between 1361 and 1370; the choir between 1380 and 1400; we may therefore take 1390 as the approximate date of the stalls. They are a little later than the Lincoln stalls, and probably contemporaneous with those of Chester. A general view of the stalls appears in Drake's Eboracum, page 522 (18).

[Illustration: Carlisle]

At Carlisle the stalls were erected by Bishop Strickland (1399-1413); Prior Haithwaite is said to have added the tabernacle work after the year 1433:[5] it would therefore be about forty years later than that at Chester (21). The lower canopy, as before, has triple gables, which are truncated ogees, but the additional front gable of Lincoln and Chester is omitted, while the pinnacled buttresses separating the canopies are carried by shafts standing on the shoulders of the stalls. The line of demarcation between the two stories, which the Lincoln and Nantwich designs had minimised, is now emphasised by making the band of quatrefoils continuous. The upper story, which in the earlier designs had had insufficient dominance, is now heightened and enlarged; it consists of three pedestalled niches instead of one; and the flanking window tracery of Lincoln and Chester, with its makeshift look, is reduced in importance, forming merely the backing of the three upper niches. The spirelet above is also greatly enriched, and additional pinnacles are introduced. A little prim the design may be in comparison with the exuberance of Lincoln, Chester and Nantwich, but the proportions are fine, and were the statuettes once more in their niches, it would be a very satisfactory composition. Such work as this has well been resembled to "a whole wood, or say a thicket of old hawthorn with its topmost branches spared, slowly growing into stalls."

Ripon

At St Asaph's cathedral the stalls and part of the canopies are ancient.[6] The cathedral was gutted by fire in 1402, and the stalls were not re-erected till 1471-1495.

Fifty years later than the Carlisle stalls were put up those of Ripon Minster (60). As two of the misericords are inscribed 1489 and 1494, they cannot be earlier than the latter year. Just as the Chester stalls were a criticism of those of Lincoln, and the Lincoln stalls of those of Ely, so the stalls of Ripon are a criticism of those of Nantwich and Carlisle. In the latter the upper story had been emphasised; at Ripon the bottom story is given the dominance; compared with the simplicity of the Carlisle design, the lower stage at Ripon, as at Nantwich, is surpassingly rich; gables and pinnacles and window tracery are loaded with beautiful detail, cusped arches are added below; finally figure sculpture is called in, and capitals and corbels are beset with tiny angels. In the string-course between the two stories quatrefoils are abandoned; it is molded, foliated and battlemented. In the upper story reappears the forest of pinnacles of Carlisle and the window tracery of Lincoln. Here, as elsewhere, the design suffers grievously from the loss of the statuettes which once ranged continuously in the upper story.

Manchester

Beverley Minster

Some twenty years later, stallwork was put up in the collegiate church of Manchester. On the north side of the choir is a curious shield with the initials of Richard Beck, a Manchester merchant, by whom all the stalls on that side were erected: the southern stalls were erected by Bishop Stanley, and at the west end of them is the shield of Stanley with the Stanley legend of the eagle and child. At Manchester craftsman ambition had to surpass Ripon and Nantwich. But the lower stages of Nantwich and Ripon were unsurpassable; so they were copied, angelettes included. The string-course is strengthened and improved by additional battlements; but undue emphasis is prevented by making it discontinuous. In the upper story, by way of change, there is a reversion to the single niche, flanked by window tracery, of Lincoln and Chester; finally, originality is asserted by surmounting the whole, in somewhat doubtful propriety, with a continuous tester, so that the canopies that cover the stalls are themselves covered and protected. This tester has a horizontal cornice with brattishing above and cornice braces between pendant pieces below. To make room for this the spirelets so much in vogue are replaced, as at Nantwich, by canopies with horizontal cresting—taking it altogether, a magnificent design, if only the Ripon stalls had not existed (62).

Beverley Minster |

Beverley Minster |

Beverley Minster |

Beverley Minster |

Then come the stalls of Beverley Minster, misericords of which are inscribed with the dates 1520 and 1524; the stalls are therefore about a dozen years later than those of Manchester. They are modelled closely on those of Manchester and Ripon. It is quite conceivable that some of the carvers may have worked successively at Ripon (1500), Manchester (1508) and Beverley (1520). As at Ripon, the lower story is made predominant, the little angels being replaced, however, by human busts—no great improvement; not that they are not full of life and interest (27, 63). The string-course is that of Manchester. The upper story has single niches flanked by window tracery, as at Manchester. The horizontal canopy of Manchester now remains over the return stalls only. On the whole it must be admitted that these stalls mark no advance. A bit of original design indeed appears at one point, where low, heavy straight-lined gables are introduced quite out of harmony with the curving ogee arches (64).

Durham

Then comes the Dissolution; a long list of Tudor monarchs reign and pass away; Stuarts take their place; Civil War follows; at length at the Restoration of 1660 the Church comes to her own again, and John Cosin ascends the episcopal throne of Durham. True to the Church of England and loyal to Gothic Architecture, he reverts to the consecrated form, and tabernacled stalls are reared once more—one of his many contributions to the cathedral and diocese of Durham (22). Nor is the design an unworthy one; nay, rather it is a distinct improvement on that of Carlisle, Ripon, Manchester and Beverley; for by abolishing the string-course, he reduces the design to the unity with which it started at Lincoln. Moreover, tall pinnacles had flanked the spirelets of Ely, Lincoln, Chester, Carlisle, Ripon and Beverley, so that really one could not see the wood for the trees; these pinnacles are now omitted, and the spirelets get their full value. Altogether a very fine design; and the little bits of Renaissance detail which here and there creep in, as in the bishop's magnificent font cover,[7] only add to its charm (66). Other examples of John Cosin's time are to be seen at Brancepeth where he was formerly rector from 1626 to 1633; the stalls, screens and pulpit of that church are simply delightful (93). More of this work is to be seen in the chapel of the Bishop's palace at Bishop's Auckland; in the church of his son-in-law at Sedgefield and at Sherburn hospital. So Gothic in spirit is this work that it has been again and again ascribed to Elizabethan times, e.g., by Billings in his County of Durham. In spite of the coarseness of some of the detail and that here and there a bit of Classical detail creeps in, it is most interesting and enjoyable; would that we had more of these delightful admixtures of Classic and Gothic forms; plentiful in Spain and France, they are rare with us.

Dunblane

The stalls in Dunblane cathedral are thought by Messrs Macgibbon and Ross[8] to have been put up in the time of Bishop James Chisholm (1486-1534). In that case they would be c. 1520. "The work is rather rough in execution, not to be compared with the more characteristic woodwork of King's College, Aberdeen"; nevertheless it is very picturesque and interesting. The introduction of the centaurs indicates Renaissance influence; the foliage carving is a rather curious mixture of late Gothic and Classic forms, such as we find elsewhere in Scottish carved work of this period. The Scottish thistle is one of the chief motifs (67).

In the chapel of King's College, Aberdeen, is a considerable amount of fine oak carved work, by far the most extensive and best of its kind in Scotland. The chapel itself, in some of its features, bears the character of the parish church at Stirling and other Scottish works of the beginning of the sixteenth century. The carved stalls, monuments, and decorative work of the interior are of the same period, but may possibly have been brought from a distance, or executed by foreign workmen engaged (like the English plumber) by the bishop. The panels are all of different design, and shew a great deal of variety combined with a sufficiently uniform effect when the work is viewed as a whole. In some of them the details are based on floral forms—thistle, vine, oak, &c.—while the conventional French fleur-de-lis is also introduced.[9]

At this point arises the question how far our stallwork was influenced by foreign design. It may be stated at once with confidence that of the great majority of the stalls the design is as thoroughly English as the oak of which they are built. We have seen that the flowing and ogee forms of the Ely tracery were designed not later than 1338, which is at least sixty years earlier than any work of the sort in France. We were able to see how by gradual modifications of the Ely design the craftsmen were able to advance slowly but assuredly to the stallwork of Lincoln, Chester, Nantwich, Carlisle, Ripon, Manchester, Beverley, Durham; the glorious chain of artistic success is complete; every link is there. But there are facts on the other side which, at any rate at Melrose, are beyond dispute or controversy. In 1846 a document was communicated to the Society of Antiquaries, London, from West Flanders, relating to a dispute at Bruges between William Carebis, a Scotch merchant, and John Crawfort, a monk of Melrose, on the one hand, and Cornelius de Aeltre, citizen and master of the art of carpentry of Bruges, on the other hand. The latter had contracted to supply certain stalls and to erect them in the abbey church of Melrose, after the fashion of the stalls of the choir of the abbey church of Dunis in Flanders, with carving similar to that existing in the church of Thosan near Bruges. The stipulated price had been paid, and the master carpenter was called to account for delaying to complete the work; whereupon he pleaded various excuses, stating that the work had been impeded by popular commotions at Bruges, during which he had been deserted by his workmen and had suffered heavy losses. It was decided that Melrose abbey should bear the cost of its transport to the town of Sluys and embarkation there for Scotland, and should make some allowance to Cornelius towards his journey to Melrose; and that they should give him and his chief carver (formiscissori) a safe-conduct for their journey and return. This document was dated 7th October, 1441.[10]

Windsor

No such wholesale example of foreign design occurs in England; nevertheless there are two important instances in which Flemish design is to be suspected; viz., in the Royal chapels at Windsor and Westminster. As regards the stalls in St George's chapel, Windsor, it is known that the tabernacled canopies were begun in 1477 and were completed in 1483; thus they took six years to make (69).[11] The canopies are known to have been made in London; the carvers being Robert Ellis and John Filles, apparently Englishmen. On the other hand the great Rood, with the statues of St George and St Edward and others, was made by Diricke Vangrove and Giles Vancastell, who are just as evidently Dutchmen; for four images the two Dutchmen were paid at the rate of 5s. per foot; for six canopies the two Englishmen received £40, say £480; i.e., about £80 of our money for each canopy. Now here we have Dutch and English carvers engaged together on what was practically one work: moreover the more artistic and difficult part of the work, the figure sculpture, is entrusted to the Dutchmen. It is to the latter probably that the general lines of the design are due. The detail is sufficiently English; not so the general design. For the Windsor stallwork is intermediate between that of Chester (c. 1390) and Carlisle (1433) on the one hand, and Ripon (c. 1490) and Manchester (1508) on the other. But it is not a development arising out of either of the earlier designs, nor was the stallwork of Ripon and Manchester in any way a development from that of Windsor.

Windsor

All the larger stallwork of the fifteenth century was, as we have seen, designed in two stories, rising into spirelets and pinnacles; at Windsor the double story, the spirelet and the pinnacle are all alike lacking. It is true that the original canopies were designed quite as much for the Knights of the Garter as for the Windsor Canons, and in the case of the former the design had to be accommodated to provide supports for the knights' helmets, mantles and swords; nevertheless this might have been accomplished without utterly breaking away from current design. The Windsor design, so far as English work goes, has no ancestry; its origin no doubt is to be found in the Netherlands. The Windsor stalls have been much tampered with. As Hollar's engraving in Ashmole's Institution of the Order of the Garter (1672) shews, over the westernmost bay on either side of the choir the canopies contained imagery and had a horizontal cresting; and all the other canopies consisted alternately of towers and spirelets; the knights being seated under the towers and the canons under the spirelets; but since the enlargement of the Order in 1786 all the spirelets have been converted into towers (71). All these towers are surmounted by wooden busts, of which the earliest go back to the time of Edward IV.; on the bust were placed the knight's helmet, crest and mantlings, which hid the busts from view; lower down, in front, hung his sword; banners were not added till a later period. At first the real sword and helm were put up; later, they were theatrical properties.

Bishop Langton's Chapel

In Winchester cathedral is stallwork of rare beauty in the Lady Chapel, which was built in the time of Bishop Courtenay, 1486-1492. In some of its details it resembles the Windsor stalls, which were completed in 1483; it is therefore feasible that some of the Windsor carvers went on to Winchester (73). South of the Lady Chapel is the chantry chapel of Bishop Langton, 1493-1500, where also the screen and coved panelling are of great excellence (72); there are no stalls.

Winchester Cathedral |

Westminster Abbey |

Henry the Seventh's chapel at Westminster was built partly as a Lady Chapel, partly to be the mausoleum of Henry VII. and his Queen, and of Henry VI.[12] Here the canopies with tower-like form and single story and with the absence of pinnacle are plainly reminiscent of those of Windsor, and as plainly distinct from current English design, as seen at Manchester in 1508 and Beverley Minster in 1520; the Westminster and Manchester canopies were being made together; but those of Westminster have no connection with the grand Northern series of consecutive designs (131). Besides Windsor influence there may be direct influence from the Netherlands; for some of the misericords are evidently from the design of a painter or engraver, the subjects being too crowded to be properly carved in wood in so limited a space. Mr J. Langton Barnard says,[13] "While looking over some engravings on copper of Albert Durer, I came across one which strikingly resembled the third misericord in the upper row on the north side; the resemblance was extremely close, especially in the arrangement and folds of the woman's dress; this is stated by Bartsch in his Catalogue (vii. 103 and 93) to be one of his earliest plates. Another plate of Albert Durer closely resembles the corresponding misericord in the lower row on the south side, as regards the position of the limbs and the folds of the drapery; while the seventh misericord of the lower row on the south side almost exactly resembles a plate by Israel van Meckenern, of two monkeys and three young ones." These stalls formerly occupied only the three western bays of the chapel; another bay was filled with stalls when the Order of the Bath was revived by King George the First; the canopy-fronts for an additional bay on each side being got by sawing off canopy-backs and putting them up as fronts. The tabernacle work is of the richest and most diversified character, varying in every canopy (73).

- ↑ Illustrated in Dart's Canterbury Cathedral, 145 and 160.

- ↑ E. Mansel Sympson's Lincoln, 277.

- ↑ Illustrated in the writer's Gothic Architecture in England, p. 269.

- ↑ A photograph of the north range of the Chester stalls forms the frontispiece of the writer's Misericords.

- ↑ Mr C. H. Purday.

- ↑ Illustrated in Murray's Welsh Cathedrals, page 267.

- ↑ Illustrated in the writer's Fonts and Font Covers, 296.

- ↑ Ecclesiastical Architecture of Scotland, ii. 105. Drawings by Mr J. B. Fulton appeared in the Builder, 1st Oct. 1898 and 2nd Dec. 1893; and by Mr A. S. Robertson in the Builders' Journal, 14th Jan. 1903.

- ↑ Macgibbon and Ross. Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland, v. 543; and Builder, lxxv. 293, in which are measured drawings by Mr J. B. Fulton.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, i. 112.

- ↑ For information relating to the Windsor stalls I am indebted to Mr W. H. St John Hope: see his paper "On a remarkable series of Wooden Busts surmounting the stall-canopies in St George's chapel, Windsor," in Archæologia, liv. 115, and the building accounts to be published in his forthcoming work on Windsor Castle.

- ↑ See the writer's Westminster Abbey, 146.

- ↑ Sacristy, i. 266.