Wood Carvings in English Churches II/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III

CANOPIED STALLS

It is probable that all the back stalls of monastic and collegiate churches had originally some form of canopy. For this there was a very practical reason, in the desire of the occupants of the stalls to have their tonsured heads protected from down draughts, which from open triforium chambers imperfectly tiled must often have been excessive. A great number of these canopies have been destroyed, usually in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, to make room for galleries, e.g., at Wells in 1590 and 1690, and Hexham in 1740.[1] In Belgium not a single set of stalls retains canopies. When the galleries were removed in modern restorations, the ancient forms of canopy were frequently not replaced, but something of modern design was put up. This should be borne in mind in examining the cresting of the stalls as it is at present; much of it is not original either in material or design.

The following is a list approximately in chronological order of some of the finest sets of stalls in cathedral, monastic, collegiate and parochial churches.

Rochester Cathedral 1227

Winchester Cathedral 1305

Chichester Cathedral 1335

Ely Cathedral begun in 1338

Lancaster Church 1340

Gloucester Cathedral 1350

Lincoln Minster 1370

Abergavenny 1380

Hereford Cathedral 1380

Hereford All Saints 1380

Chester Cathedral 1390

Nantwich 1390

Stowlangtoft 1400

Wingfield, Suffolk 1415

Higham Ferrers 1415

Norwich Cathedral 1420

Carlisle Cathedral 1433

Sherborne Abbey 1436

Hereford St Peter 1450

St David's 1470

Windsor 1480

Ripon 1500

Manchester 1508

Westminster 1509

Christchurch 1515

Bristol 1520

Dunblane 1520

Beverley Minster 1520

Newark 1525

King's College, Cambridge 1533, 1633, 1676

Aberdeen 1520

Cartmel 1620

Brancepeth 1630

Durham Cathedral 1665

Bishop Auckland Chapel 1665

Sherburn Hospital, Durham 1665

Sedgefield 1680

St Paul's Cathedral 1697

Canterbury Cathedral 1704

Rochester

The stalls of the churches of Ratzburg illustrated by M. J. Gailhabaud, vol. iv., seem to be of the middle of the twelfth century; they are of clumsy design and in a fragmentary condition. At Hastières and Gendron-Celles, both near Dinant, Belgium, are simple stalls of the thirteenth century.[2]

In France the chief examples are those in Notre Dame de la Roche; fragments occur also in Poitiers cathedral and the church of Saulieu.[3]

The earliest stallwork of which we have remains is in Rochester cathedral (30). From fragments which remained it was found that the stalls had been about 3 feet 6 inches high, and had hinged seats only 13½ inches from the floor; there was a space of 2 feet 9 inches between the seat and the form in front, and the seat was 2 feet deep.[4] There was but a single row of stalls, and the forms were very low; only 22¼ inches above the platform on which they stood. They are too low to have been used as book rests; which indeed would have been unnecessary, as the monks knew the Psalter and their services by heart; the only service books employed being the big books which lay on the great lectern in the gangway of the choir. It is probable that the forms were of use at certain parts of the service when the monks were prostrati super formas.[5]

Westminster

At Westminster the original stallwork of the choir has perished; fortunately, however, a sketch of a portion of it has been preserved (31).[6] That the sketch is trustworthy may be seen by comparing it with the description of the stalls by Dart in his Westmonasterium (1742), who says that "the stalls were crowned with acute Gothic arches supported by pillars." The sketch shews slender shafts with molded capitals, neckings and bases, supporting lancet arches which are without cusps; at the back are trifoliated lancets. The work belongs to the period when the eastern bays of the nave were built, viz., 1258 to 1272. In Henry VII.'s chapel are two misericords of conventional foliage; no doubt they belonged originally to Henry the Third's choir. A valuable and little known example of a thirteenth century stall survives at Hemingborough, Yorkshire (87). At Peterborough also fragments of stalls of the same century remain; but they have backing of Jacobean character (32). At Gloucester a fragment of a thirteenth century stall has been preserved behind the seat of the Canon in residence.

Peterborough

Apart from the above, we seem to have no stallwork of earlier date than the fourteenth century. Of that period the earliest and perhaps the most beautiful is that in Winchester cathedral. The pulpit was given by Prior Silkstede, whose name is inscribed on it; he was prior from 1498 to 1524; the desks and stools of the upper tier have the date 1540. The canopies are of one story. Each is surmounted by a straight sided gable or pediment, which is crocketed and finialled and has compound cusping. The upper part of each gable is perforated with a multifoiled trefoil. Below, the stall is spanned by a broad pointed arch, which is subdivided into two pointed and detached arches, with foliated cusps. These two minor arches carry circles with varying tracery. At the back of each stall (35) is a broad arch containing a pair of detached pointed trifoliated arches supported by shafts whose capitals are alternately molded and foliated. These two small arches carry a circle within which is inscribed a cinquefoil, cusped and foliated. The spandrils between each pair of containing arches at the back of the stalls are occupied by foliage admirably carved, in which are figures of men, animals, birds, &c. There is no pronounced ogee arch anywhere, though there is a suspicion of one where the open trefoils of the gables rest upon the containing arches. The tracery too of all the circles is geometrical, i.e., composed of simple curves; there is no flowing or ogee tracery with compound curves. It may be assumed therefore that the work is earlier than c. 1315. On the other hand the foliage of the spandrils has pronounced bulbous or ogee curves and the pediments contain compound cusping; both features being characteristic of ornament of the first half of the fourteenth century.

Winchester Cathedral

Winchester Cathedral

Taking all into account, 1305 may be taken as an approximate date for this superb work. It is usually assigned to the year 1296, on the ground of similarity of design to that of the Westminster tomb of Edmund Crouchback who died in that year; but that is to forget that he died in debt, leaving instructions that he was not to be buried till his debts were paid: it is likely therefore that his tomb is several years later than 1296; indeed, except that its main arch has not ogee arches in its cusping, it is not much earlier in design than the adjoining tomb of Aymer de Valence, who died in 1324. Comparison may be made also with the monument in Winchelsea church of Gervase Alard, who was still alive in 1306; and with the monuments in Ely cathedral of Bishop Louth (ob. 1298) and in Canterbury cathedral of Archbishop Peckham (ob. 1292).

Chichester

On the other hand in Chichester cathedral (36), the ogee motive is supreme. There are no more pointed arches; every arch is an ogee; and the cresting consists of wavy tracery surmounted by a battlement. The cusping of the upper ogee arches is compound; the foliage of pronounced bulbous character. It is unlikely that this work can be much earlier than that of the Ely stalls, which were not begun till 1338. On the evidence of costume and armour it would seem that the misericords were in course of execution between c. 1320 and c. 1340; the stallwork would probably be the last part of the work; and as the Chichester Records are reported to assign the work to Bishop John Langton, who died in 1337, we may assign 1335 as an approximate date to the stalls.

Ely

When we come to Ely, we deal with ascertained dates; it is known that the stalls were commenced in 1338. They are on a noble scale, but have been "improved" by restorers, who among things have actually inserted Belgian carvings in the upper niches. These stalls have two distinct tiers of canopies, so that they rise to a considerable height. Each of the lower canopies has a pointed arch with compound ogee cusping; above each of these is a niche with three gabled canopies carrying a low spirelet which is flanked by ornate pinnacles; the whole forming a very beautiful composition. It is a great advance from the one-story design of Chichester (36), to the two stories of Ely.

Gloucester

The great east window of Gloucester choir was glazed c. 1350; by which date half of the stalls were ready. The northern stalls are the work of Abbot Staunton (1337-1351); the southern of Abbot Horton (1351-1377); they replace thirteenth century stalls erected by Elias de Lideford. The design of the stalls is curious and interesting. In the canopy the leading motif is the "bowing ogee," repeated twice; it is well seen in the contemporary work of the Percy monument at Beverley and the arcading of Ely Lady Chapel. The upper and acutely pointed ogee is finialled, and is flanked by battlemented and crocketed pinnacles; behind is a battlemented, crocketed and finialled spirelet. Behind the spirelets is arcading composed of window tracery; and above the arcading is a crested horizontal cornice. At first sight the design looks no more advanced than that of Ely; but if the tracery of the arcading be examined, it will be found that the three lower lights have supermullions, and that the centre-pieces are straight-sided. In woodwork, as in stone, it was at Gloucester that the reign of the straight line commenced (38).

Lancaster

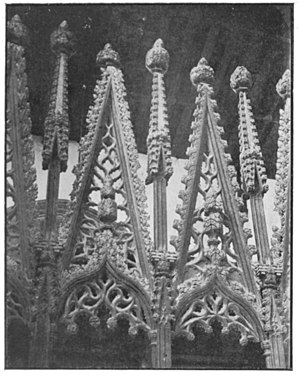

Then comes a group of stalls which it is not easy to date, but all of which are redolent of fourteenth century inspiration; those of Lancaster church, those of the cathedral and All Saints' church at Hereford, and those of Abergavenny priory and Norwich cathedral. The Lancaster stalls are the chef-d'œuvre of English woodwork, wonderful alike in design and execution; in woodwork they must have been in their day unrivalled; in stone they find a compeer in the marvellous detail of the Percy monument and in the still finer work at the back of the reredos in Beverley Minster. They do not shew the slightest sign of the revolution of design which had commenced in Gloucester transept c. 1330, and which by the end of the century was to overspread all England; they are the natural development of the design of the first half of the fourteenth century carried forward to an extent for which the only parallel is to be found in the highly developed Flamboyant detail of French, Spanish, and Flemish design of the middle and latter part of the fifteenth century. So inordinately Flamboyant are the traceries (41, 42) that one would unhesitatingly ascribe them to Continental artists did one not see the touch of the English craftsman everywhere; compare for instance the tracery shewn at the top of page 42 with that of the west window of the far-away church of Snettisham, Norfolk.[7] One hesitates to assign to the Lancaster work such an early date; but if the Percy monument was in course of erection, as we know it was, soon after 1340, it is quite possible that the Lancaster stalls also date before the arrival of the Black Death in 1349-50. After that date a great change came over design; the rich exuberance of Ely Lady Chapel, the Easter sepulchres, sedilia and piscinas of mid-Lincolnshire and the Percy monument at Beverley, appear no more. Any lingering hesitation one may have, however, is removed by a scrutiny of the moldings, especially those of the capitals, neckings and bases;[8] they are just those which were in fashion c. 1340.

Lancaster |

Lancaster |

Lancaster

The Lancaster stalls may be regarded as the Flamboyant version of the stallwork of Winchester cathedral, with which they should be compared (34). Like the Winchester stalls, they are but one story high; they do not aspire to the two stories of Ely and Norwich. There is a tradition, unsubstantiated, that these stalls came from Cockersand abbey in 1543. But St Mary's, Lancaster, was a priory church attached, first, to the abbey of St Martin, Sées, in Normandy, and then, when alien priories were suppressed, transferred to Sion abbey, Middlesex. In 1367 Lancaster priory had a revenue of £80, say £1,200 per annum, and was quite able to provide stalls for itself.

Hereford Cathedral

The lower part of each canopy consists of an ogee arch; this is somewhat low, but in compensation is surmounted by an exceptionally lofty pediment. Both ogee arch and straight-sided pediment are filled with perforated tracery. All this tracery, both above and below, differs from bay to bay; the craftsman would not and could not repeat them; he was simply overflowing with inventive design. The tracery of the ogee arch rests on an arch, usually an ogee arch, which is cusped in ogee, semicircular or segmental curves, tipped with charmingly diversified pendants of faces, fruits and foliage; the interval between the two arches is filled with a network of compound curves—a labyrinth of beautiful forms—enticing the eye to attempt to follow their ramifications by ever new routes; each little pattern is cusped, and each has the ogee curve at one end or both ends, or at one side (41). Equally ingenious and diversified is the tracery which fills up the tall pediment. The broad band of foliated ornament, which forms a kind of continuous crocketing, in spite of much mutilation remains the richest example in English woodwork.[9] Notice too the little masks which immortalise the features of the Lancaster men of 1340; sometimes no doubt they represent the carvers themselves.

Hereford All Saints'

Hereford All Saints'

In Hereford cathedral the stalls are of one story and have a horizontal cresting. At the back of each stall is an ogee arch, and in front a bowing ogee arch; there is some lack of contrast. The sides of the upper ogees are prettily flanked by graduated window tracery; and the great multiplication and predominance of the vertical line makes it likely that the stalls were put up rather after than before the Black Death (43).

Abergavenny

Wingfield

At All Saints', Hereford, is a range of stalls of remarkable beauty. They have the bowing ogees, the compound cusping, the intersecting wavy tracery of the first half of the fourteenth century; yet the cusping and tracery are not in the early manner. In the cathedral the bowing ogees meet at an angle of nearly 45°; at All Saints', they project but slightly, meeting with a very obtuse point. All Saints' has ogee canopies under a coved horizontal tester with supporting shafts, as in the cathedral. In the latter the cornice of the tester on the south side has a perforated battlemented parapet; that on the north (43) has brattishing; at All Saints' both sides have brattishing, but the pattern is not the same. Hereford suffered much from the Black Death of 1350, and it is not likely that a parish church would be able to afford such costly stalls before the last quarter of that century. We may suggest 1380 as a probable date. It must be remembered that nearly all changes in mediæval design originated with the stone mason; it was some time before they were caught up by the craftsmen in other materials (44).

To the exquisite stallwork of Abergavenny the remarks made on that at All Saints', Hereford, again apply; it is redolent of the inspiration of the first half of the fourteenth century; but its effects are gained in a totally different way: this also may be assigned to the last quarter of the fourteenth century;[10] say c. 1380 or later (46).

The stalls at Wingfield, Suffolk, might date from 1362, when the church was made collegiate; but much work was done in the time of Michael de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, and his wife, Catherine Stafford; he died in 1415; the badges of Wingfield and Stafford—a wing and the Stafford knot—are seen on the arches between the de la Pole chapel and the chancel. The design of the stalls and desks is such as might be expected early in the fifteenth century, especially in East Anglia, where fourteenth century design lingered long (46).

Norwich Cathedral

At first sight the Norwich stalls might seem to belong to the first half of the fourteenth century; as in the stalls of Chichester, the lower canopies have ogee arches; while there is a second story above, as at Ely. The exuberance of earlier design is present in the cusping and the crockets; notice how the crockets vary from bay to bay, one set being actually composed of hawks. Nevertheless supermullions rise from the apex of each minor arch of the window tracery of the spandrils, and are conclusive evidence that the date is considerably later. The stalls and misericords below are of two periods. In the earlier set of twenty-four the seats are polygonal; the armour depicted is that of the last half of the fourteenth century, and there are arms of donors who died respectively in 1380, 1400 and 1428; so that we may assign the approximate date of 1390 to this set of misericords. The remaining thirty-eight misericords have seats curved on plan, and, according to Mr Harrod, are not later than the middle of the fifteenth century. Now the canopies extend above both sets of misericords; the probability therefore is that they were put up together with the second set of misericords. But there is one curious bit of evidence in the canopy work itself, which is here illustrated (48); viz, that one set of crockets consists of hawks with jesses. Now on the arms of John Wakering, who was bishop from 1416 to 1425 are three hawks' lures;[11] that being so, the probability is that the whole of the canopies, and the second set of misericords as well, are of the approximate date of 1420. Though so much later than the Ely stalls, the absence of the spirelet and the retention of the horizontal cornice marks this, in spite of much beauty of detail, as a retrogressive design.

The stalls of Sherborne abbey, Dorset, are somewhat of a puzzle (49). The arch design, with the compound cusping, is in accordance with that of the lower story of the Ely stalls of 1338, except that the arches are semicircular or nearly so; but fourteenth century exuberance and versatility have faded away; the design is regular, symmetrical, prim. There was a great fire in Sherborne Minster in 1436; the piers of the choir are still reddened with the flames; the former stalls would certainly be consumed, and these no doubt are their successors.

Sherborne

The stalls at Hereford St Peter and Stowlangtoft are illustrated to shew that not only monastic and cathedral churches, but parish churches also possessed abundance of fine stallwork. Stowlangtoft is a remote Suffolk village; but possesses a magnificent set of the original carved benches in the nave and stalls in the chancel (91). The woodwork is probably of the date of the church, which seems to have been rebuilt late in the fourteenth or early in the following century; the Hereford church is a town church; its stalls appear to be well on in the fifteenth century (89).

In Bristol cathedral the stalls consist of a range of traceried panels surmounted by a horizontal coved cornice. There are now twenty-eight stalls. They bear the arms and initials of Abbot Elyot (1515-1526).

At St David's a totally new departure occurs in stall design; the motif now being clearly taken from an oak screen surmounted by a parapetted loft (109). In the fourteenth century stalls illustrated the ogee arch was the characteristic feature; in the fifteenth century the fashion was to take an elongated ogee arch, and truncate it, employing only the upper portion with the concave curve; these semi-ogees occur everywhere both in stone and wood; they are well seen at St David's in the backing of the stalls. This work has superseded that which was ordered to be put up in 1342 by Bishop Gower, only one fragment of which remains; it was found above the present canopy and consisted of a finialled ogee canopy, agreeing nearly in detail and character with those portions of the Bishop's throne which are of Gower's time.[12] The present stalls, misericords, stall backs and canopy are all fifteenth century work; on the dean's stall (in this cathedral, as nowadays at Southwell, the bishop was also dean) are the arms of Bishop Tully (1460-1481), and on the Treasurer's stall is the name of POLE, who was treasurer in the bishop's latter days. The parapets above cannot have been added till the sixteenth century; for they terminate to the east in scrolls of the form common in cinquecento work.

- ↑ Views of galleried choirs may be seen in Britton's Cathedral Antiquities; Norwich, ii. 13, Oxford, ii. 10.

- ↑ Illustrated in Maeterlinck, La genre satirique dans la sculpture flamande et wallonne, page 12.

- ↑ See Viollet-le-Duc's Dictionnaire, viii. 464.

- ↑ See C. R. B. King in Index to Spring Gardens Sketch Book, ii. 46, and Plate XLVI.

- ↑ Hope's Rochester Cathedral, pp. 110, 111.

- ↑ It is illustrated in Professor Lethaby's Westminster Abbey, p. 23, from Sandford's Coronation of James II., and is reproduced above.

- ↑ Illustrated in Gothic Architecture in England, 481.

- ↑ See John O'Gaunt's Sketch Book, vol. i.

- ↑ Here, as always, one has to recognise the technical and artistic excellence of Mr Crossley's photography; he has even reproduced the cobwebs.

- ↑ They are ascribed to the fourteenth century by Mr Octavius Morgan in Monuments of Abergavenny Church.

- ↑ My attention was directed to these arms by Mr W. H. St John Hope.

- ↑ Jones and Freeman's St David's, pp. 87 and 91.