Wood Carvings in English Churches II/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V

RENAISSANCE STALLWORK

Thus far the stallwork has been wholly of Gothic design, or nearly so. We now come to the great change of style, the reversion to the Classic art of ancient Rome, which goes by the name of the Renaissance. Of this the chief representatives left to us are the stalls of Christchurch, Hants; King's College, Cambridge; and Cartmel, Lancashire. The stalls and misericords of Christchurch, as we see them now, are a patchwork of portions of work of several periods framed together at some more or less recent epoch; there are at least two styles of Renaissance work, and three or more of Gothic. The earlier Renaissance work, which is seen in most of the misericords and on the stall backs is that of William Eyre who was Prior from 1502 to 1520 (2). There are fifty-eight stalls; of the misericords twenty-six have been stolen or destroyed. The early date of this work makes it of exceptional importance in the history of the introduction of Renaissance art into England. One special feature of the work is the portrait panels. These also occur in a cupboard preserved in Louth church, Lincolnshire, where the panels have what look very much like portraits of Henry VII. and his queen, Elizabeth of York. It goes by the name of the "Sudbury hutch" and was the gift of Thomas Sudbury, who was vicar from 1461 to 1504: it is therefore of the time of Henry VII. These "portrait cabinets" had a great vogue in the reign of Henry VIII., and throughout the sixteenth century. Then come three important tombs by Torrigiano, executed between 1509 and 1518, that of Henry VII. and his Queen and that of Margaret Beaufort at Westminster and that of Dr Young in the Rolls chapel. Almost as early, if not quite so, is Prior Eyre's work at Christchurch. Then comes Cardinal Wolsey's work at Hampton Court, 1515 to 1525; the beautiful Marney tomb at Layer Marney, Essex, 1523; the mortuary chests in the cathedral, and the screen work both in the cathedral and in St Cross, Winchester, c. 1525; the chantry chapel of Prior Draper at Christchurch, 1529, and that of Lady Salisbury, which may be a year or two earlier; and the screen at Swine church, Yorkshire, dated 1531. Then follow Henry VIII.'s hall at Hampton Court, 1534; and the screen at King's College, Cambridge, 1533.

Christchurch

Christchurch

So that the Christchurch work stands very high on the list and deserves much more attention than it has received. The general outline of the stalls themselves is Gothic, the chief divergency being in the supports of the elbow rests and seats. Among the shafts are examples of the honeycomb form which is almost the only bit of Renaissance detail in the canopies of the Westminster stalls. At the back of the stalls are very vigorous carvings of classical dragons, serpents, hounds and human faces (76). To these last fanciful attributions have been made; e.g., one has been imagined to represent Catharine of Arragon between Cardinal Wolsey and Cardinal Campeggio (77). These portrait busts have a wide distribution; they occur in wood, stone and terra cotta. Noble examples are those in terra cotta at Hampton Court, which were undoubtedly imported by Cardinal Wolsey direct from Italy.[1] Others no doubt are the work of Italians resident in England in the first half of the sixteenth century, when Italian art and Italian literature were equally the fashion with the cognoscenti led by Henry VIII. and Wolsey; e.g., the fine bust of Sir Thomas Lovell by Torrigiano, now in Westminster Abbey.[2] These portrait busts have a wide range—from Essex westward to Somerset, Devon and Cornwall; e.g., North Cadbury, Somerset; Lapford, Devon, and Talland, Cornwall; several also occur at Hemingborough, Yorkshire. The probability is that the Italian artists entered the kingdom at Southampton; and that a few found work at Christchurch and in the south-west, but that the main body proceeded eastward to Winchester, Basing, London and Layer Marney; they have left one memorial at Oxford beneath a window at Christ Church.[3]

King's College, Cambridge

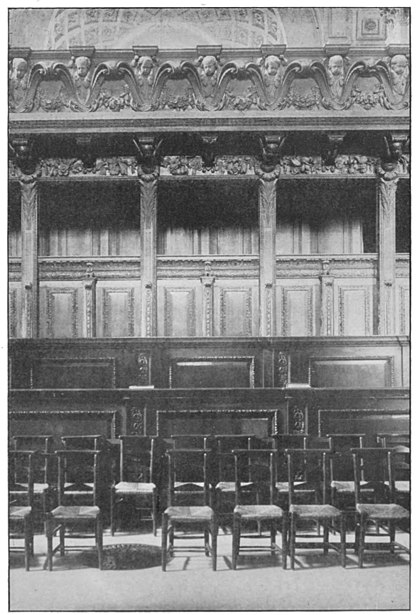

Next come the famous screen and stalls of King's College, Cambridge—"the finest woodwork this side of the Alps." Harmonious as is the general effect of the stallwork, it was executed at three different periods. The stalls were ordered to be made by Henry VI. in his will, but were not put up till much later. About 1515 an estimate was obtained for 130 stalls, which it was found would cost about £12,000 of our money, i.e., about £92 each. On the screen, which is part of the same work, are the arms, badge and initials of Anne Boleyn, who was at the height of her influence between 1531 and 1535; the stallwork may be ascribed to the same period, but as yet the stalls had plain backs. In 1633 Mr Thomas Weaver presented the large coats of arms which are seen on the backs of the stalls (78). The cresting was made between 1675 and 1678 by Thomas Austin, following more or less the style of the work below.[4] The screen is more completely Italian in treatment than any other work of the time, all the moldings being Classic; it is practically certain that the general design and most of the work must have been done by Italians. The design of screen and stalls alike is to be regarded as an isolated example, complete in itself. It did not grow out of anything that went before it in England, nor did it develop into anything else in England afterwards.[5]

More Classical still in design—an entablature with architrave, frieze and cornice superseding the semicircular arches of the Cambridge stalls—is the superb woodwork at Cartmel, Lancashire. From the Dissolution up to 1620, the choir of Cartmel priory church was roofless; the canopies of the stalls must have perished; the stalls themselves remain, bearing the mark of long exposure to the weather. In 1620 it is recorded[6] that George Preston of Holker, who died in 1640, not only reroofed the chancel, "but decorated the quire and chancel with a profusion of curiously and elaborately carved woodwork" (80).

Cartmel

Cartmel

Cartmel was a priory church of Austin Priors, with an income at the Dissolution of £90, say £1,000. There are twenty-six stalls; above the doorways are inscriptions in gold letters from the Psalms. The architrave is supported by shafts which have Corinthian capitals, round which cling in delightful fashion delicate tendrils and fruit of the vine. On the shafts also are emblems of the Passion; in the illustrations may be recognised the cross, the ladder, the buffet, the pillar of scourging, the hammer and the nails. At the back is delicate tracery work, reminding one of the Gothic tracery of the screen of St Catharine's chapel in Carlisle cathedral. The whole design is full of grace and charm; above all in the delicate tendrils of the vine coiling round the shafts; one's first thought is to class it with the exquisite scrollwork of the churches of S. Maria dei Miracoli at Brescia and Venice, and with the work of the Italian artists in England in the time of Henry VIII. For as a rule, says Mr Gotch,[7] "with the close of the first half of the sixteenth century we come to the end of pronounced Italian detail such as pervades the tiles at Lacock abbey and characterises other isolated features in different parts of the country. The nature of the detail in the second half of the sixteenth century," and in the seventeenth century, "is different; it no longer comprises the dainty cherubs, the elegant balusters" (cf. the King's College stalls) "vases and candelabra, the buoyant dolphins and delicately modelled foliage which are associated with Italian and French Renaissance work, but indulges freely in strapwork curled and interlaced, in fruit and foliage, in cartouches and in caryatides, half human beings, half pedestals, such as were the delight of the Dutchmen" who had superseded the Italian artists. In the Cartmel stalls the one feature which is pre-eminently Jacobean is to be seen in the character of the busts in the frieze; if they are compared with those at Christchurch (77), they are seen at once to be of seventeenth and not of sixteenth century design. Setting those aside, the design is purely that of the Early English Renaissance, as practised by Italian artists. It is one of the most remarkable examples of "survival" in design in the range of English art, and as beautiful as it is belated—a whole century behind the times.

St Paul's Cathedral

In 1697 the choir of St Paul's cathedral was opened for public worship. The stalls differ considerably in type from those of Pre-Reformation days, as it was necessary to provide seats for the Lord Mayor and Corporation of London as well as closets at the back to accommodate the wives and families of the canons. By the removal of the western screen in the time of Dean Melvill, appointed 1856, the appearance of the choir has been completely changed. The exquisite carvings of Grinling Gibbons, says Dean Milman,[8] are not merely admirable in themselves, but in perfect harmony with the character of the architecture. He even goes so far as to say that they rival, if they do not surpass, all mediæval works of their class in grace, variety and richness; and keep up an inimitable unison of the lines of the building and the decoration. In the words of Horace Walpole, "there is no instance of a man before Gibbons who gave to wood the loose and airy lightness of flowers, and changed together the various productions of the elements with a fine disorder natural to each species." It is doubtful whether Grinling Gibbons was of Dutch or English birth. He was discovered by Evelyn in a poor solitary thatched house near Sayes Court carving a Crucifixion after Tintoretto. In this piece more than a hundred figures were introduced; "nor was there anything in nature so tender and delicate as the flowers and festoons about it; and yet the work was strong." He asked Evelyn £100 for it. The frame, says Evelyn, was worth as much. Evelyn introduced "the incomparable young man" to the King and to Wren, and his fortune was made. Malcolm in his Londinium Redivivum calculates that the payments made to Gibbons for his work in St Paul's amounted altogether to £1,337. 7s. 5d.[9]

Space fails to tell of many noble examples of eighteenth century stallwork.[10] In spite of an enormous amount of destruction, e.g., by the vandals in charge of Canterbury cathedral, much still remains and awaits the historian. A fine drawing of the stallwork put up in 1704 in Canterbury choir will be found in Dart's Canterbury. The throne, carved by Grinling Gibbons, was given by Archbishop Tenison; the pulpit, two of the stalls and other fittings by Queen Mary II.;[11] all this has been swept away, except some pieces worked into the return stalls, to make way for stalls of the usual brand of Victorian Gothic.

- ↑ The Hampton Court busts are by Giovanni de Majano, who in 1521 demanded payment for ten "medallions of terra cotta." They cost £2. 6s. 8d. each. R. Blomfield's History of Renaissance Architecture in England, 3.

- ↑ Illustrated in the writer's Westminster Abbey, 197.

- ↑ See also the illustration of the chair made c. 1545 for Dorothy Mainwaring, page 123.

- ↑ See Willis and Clark, i. 516-522.

- ↑ Gotch's Early English Renaissance, 29, 254.

- ↑ Annales Caermoclenses, by James Stockdale; Ulverston, 1872, p. 76.

- ↑ Early Renaissance Architecture in England, 38.

- ↑ Annals of St Paul's, 447.

- ↑ Measured drawings of the stalls of St Paul's by Mr C. W. Baker appeared in the Building News, 1891, pages 108 and 358.

- ↑ The Renaissance woodwork ousted from Worcester cathedral by Sir Gilbert Scott found a resting-place in the church of Sutton Coldfield (R. A. D.).

- ↑ Willis' Canterbury Cathedral, 107.