Wood Carvings in English Churches II/Chapter 6

CHAPTER VI

STALLS IN PARISH CHURCHES

Sall |

Trunch |

Stalls are found, but rarely with canopies, in many parochial, as well as in monastic, collegiate and cathedral churches. In the latter of course the object of them is obvious; they were intended to accommodate a large body of monks or canons with their vicars and the choristers. But they are found sometimes in the churches of quite small parishes, e.g., Sall, Trunch, Ludham, Burlingham St Edmund's in Norfolk, Weston-in-Gordano, Somerset, Norton in Suffolk, Ivychurch[1] in Romney Marsh, where it is pretty certain that in most cases the church was served by a single parish priest merely. At Ingham, a parish in the Norfolk Broads, there are ten stalls in the chancel; at Stowlangtoft, Suffolk, there are six stalls; and so with numerous others. How early parochial chancels had stalls is difficult to say. No existing examples are earlier than the thirteenth century. But a curious fact about the growth of our parish churches, to which attention has not hitherto been directed, may throw some light on the subject. In early Anglo-Saxon days the normal and most common type of parish church was one which had an aisleless nave and chancel. In early Norman days also this was the most common type. In all the above churches, whether Anglo-Saxon or Norman, the chancel, whether rectangular or apsidal, was quite small. Comparatively few, however, of these chancels remain small. In the vast majority of cases they have been enlarged. Either the old chancel has been retained but has been lengthened, or it has been broadened as well as lengthened, thus producing an entirely new chancel. In most cases it happened that, in the long history of the church, aisles were thrown out afterwards, or transepts, that later the nave was lengthened westwards and was heightened to accommodate clerestory windows, and still later a western tower was added and perhaps a spire. But the enlargement of the chancel sometimes took place without any of the other alterations, and where that is so, i.e., where the church retains a comparatively small nave, the enlarged chancel bulks up very lofty and spacious, seemingly quite out of scale to the rest of the church: in some examples the chancel is actually loftier than the nave. A church with a chancel so disproportionate strikes the attention at once as one demanding explanation. Large numbers of such abnormally big chancels survive. In Kent and Sussex many of them are of the thirteenth century; e.g., Littlebourne; while over England one is struck with the very large number of lofty and spacious chancels of the fourteenth century; e.g., Norbury, Derbyshire; Oulton, Suffolk. In numerous cases the enlargements of the chancel took place more than once. At Boston the church was rebuilt with a fine chancel c. 1330; but by the end of the century even this vast chancel was judged inadequate, and it was extended still further to the east.

Hemingborough Church

What then is the explanation of this furore for enlargement of chancels? In considering the answer, it must be borne in mind that, ritualistically, the English parish church was always tripartite; consisting of nave, choir and chancel. In churches of the Iffley type, i.e., with a central tower, it was also architecturally tripartite. But even in churches which architecturally were bipartite, i.e., which consisted merely of a nave and chancel, the chancel was divided into two parts, choir and sanctuary, the distinction between them being marked by a change of level. Which part then was it that was found inadequate, the sanctuary or the choir? Not the former; it was not then cumbered with altar rails; the purpose they serve nowadays was served by the screen which every church possessed, guarding the entrance to the chancel; and the sanctuary was quite large enough for the celebrant at the Mass, with as a rule a solitary assistant, the parish clerk. It must have been the choir that was too small for the seats which it was desired to place in it. We conclude therefore that seats were common even in small village churches as early as the thirteenth century, if not before. Documentary evidence to that effect we have not. But in later days there is definite evidence as to the practice of putting stalls in the chancels of parish churches. In Hemingborough church, Yorkshire, there remain stalls of graceful thirteenth century design (87). Now this church in the thirteenth century was parochial; it did not become collegiate till 1426. A series of entries of the cost of choir stalls is preserved for the parish church of St Mary at Hill in the City of London. In the year 1426 there was "paid to three carpenters for the stalls of the quire, 20d." In the following year there was paid "for the stalls of the quire" the large sum of £12 (= £150); it would seem that it was about this time that a complete new set of stalls was put into the choir. In the same year, 1427, there was "paid for stalls in the quire, 16s. 6d."; and "for a quire stool, 7s. 10d." In 1501 a payment was made "for mending of desks in the quire"; in 1509 "for nails and mending of a bench in the quire, 1d." In 1523 there was "paid for a long desk for the quire, 3s."; in 1526 "for the stuff and making of a double desk in the quire, 5s." Then, in Protestant days, there was "paid for mending the desk and settles in the chancel, 2s." At this church the lower part of the bench was made to form a box or chest.

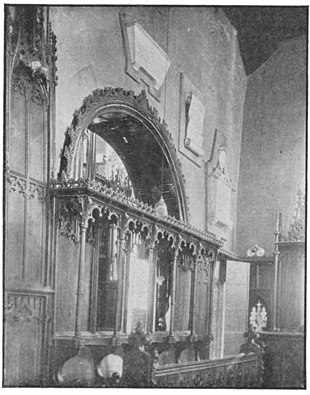

Hereford St Peter's

Who then sat in these stalls? The common theory is that they were intended for the use of the rector or vicar and the parish clerk, and of any chantry priests who might be attached to the church. This no doubt is true as far as it goes. At St Maurice, York, a complaint was made at the visitation in 1416 to the effect that the desks in the choir, viz., those where the parish chaplain and the parish clerk were wont to sit, are unhandsome and in need of repair: "Dicunt quod deski in choro, tam ex una parte quam ex alia, ubi saltem capellanus parochialis et clericus parochialis sedere usi sunt, nimis deformes et indigent reparacione."[2] To many churches also, but by no means to all, chantry endowments were made; i.e., money was left that masses might be said for ever for the repose of the soul of the donor by a priest, other than the rector or vicar, specially appointed for that purpose. It is commonly supposed that these chantry priests were concerned only with the special altars at which they ministered. But that this was not the case, at any rate universally, is apparent from the terms of the institution of the Willeby chantry in Halifax parish church. The deed is dated 10th June 1494. Amongst other regulations it contains the provision that the chaplain is to attend in person in the choir of the church on every Sunday and Holy Day in his surplice, at matins, mass and vespers, and to take his part in the reading and chanting, as directed by the vicar, and in accordance with the constitutions of the Metropolitan Church. "Item volo et ordino quod predictus Tho. Gledhill, Capellanus modernus, et omnes alii Capellani, ... temporibus futuris nominandi, singulis diebus dominicis et festivis personaliter sint presentes in choro ejusdem Ecclesie temporibus matutinarum missarum et vesperarum, suis suppeliciis induti, et legant et psallent, prout Vicario ejusdem Ecclesie pro tempore existenti decenter et congrue videbitur expedire, ut in constitutionibus Ecclesie Metropolitane proinde constitutis plenius liquet." Assuming then that the same rule applied also to the incumbents of the other chantries, there would be a regular body of clergy to take part in the choir offices.[3]

Instances might be multiplied to any extent of the obligation laid on chantry priests to attend and assist the rector or vicar in the services. Thus at Rothwell in 1494 the chantry priest attached to the altar of Our Lady was not only required by the foundation deed to celebrate Mass and other service daily at this altar, but was directed to be in the high choir all festival days at matins, Mass, and evensong. In 1505 Margaret Blade, widow, endowed a chantry of Our Lady in Kildewick parish for a priest who, in addition to his special duties, was to help Divine service in the choir and to help the curate in time of necessity.[4] Sometimes quite a considerable number of chantry priests were attached to a parish church. When all chantry endowments were confiscated by Edward VI., the loss of the services of the chantry priests was in many cases severely felt. At Nottingham indeed the parishioners of St Mary's made formal protest; stating that in their parish there were "1,400 houseling people and that the vicar there had no other priest to help but the two chantry priests."[5] We may take it therefore that seats in the chancel were required not only for the parish priest and the parish clerk, but in some cases for chantry priests as well.

But the above explanation does not cover the whole ground. There are often many more stalls than could be used as above. And in some churches there were no chantry priests at all, and yet there are stalls. Who else then occupied seats in the chancel? Some of the stalls probably, usually but a few, may have been occupied by laymen even so early as the thirteenth century.

As regards the occupancy of seats in the chancel it is quite clear that it has always been the wish of the Church that they should be reserved for the clergy and that no laymen should be admitted. It is equally clear that the Church has never been able to carry out the injunction. In the Trullan Council of 683 or 692 it was laid down, "Nulli omnium liceat, qui quidem sit in laicorum numero, intra septa sacri altaris ingredi, nequaquam tamen ab eo prohibita potestate et auctoritate imperiali, quandoquidem voluerit Creatori dona offerre, ex antiquissima traditione"; i.e., "No layman may enter the chancel, except the Emperor, who by venerable tradition is allowed to do so when he wishes to present offerings to his Maker." But this does not explicitly allow the Emperor to sit down in the chancel. And even this much was objected to by many; for a gloss follows: "Nemo liceat laico intra, &c." ... "Adulatione et timore victi, per gravem errorem concedunt imperatori, quod magna cum laude sanctorum patrum Ambrosius Theodosio negavit"; i.e., "The permission given to the Emperor was given under the influence of adulation and timidity, and the action of St Ambrose in refusing it to the Emperor Theodosius was greatly applauded by the Fathers." But it was a perilous thing to exclude emperors, and what was conceded to emperors was claimed by princes, and what was conceded to princes was claimed by and had to be conceded to the nobility generally. So in Scotland in 1225 by an episcopal order the King and his nobles also were allowed to stand and to sit in the chancel: "Ne laici secus altare, quum sacra mysteria celebrantur, stare vel sedere inter clericos presumant, excepto domino rege et majoribus regni, quibus propter suam excellentiam in hac parte duximus referendum." And if the nobles, then certainly the patron of the living could not be excluded from a parochial chancel. So in the diocese of Worcester in 1240 a canon was agreed to that patrons as well as high personages might stand in the chancel: "nec laici stent in Cancellis dum celebrantur divina; salva tamen reverentia patronorum et sublimium personarum"; in Lincoln diocese also Bishop Grosstête in 1240 restricts the permission to the patron. Again in 1255 in Lincoln diocese the patron or any other "venerable" person was allowed to sit and stand in the chancel. Archbishop Greenfield of York (1304-1315) found it necessary to make a rule against laymen intruding into the choir during service. So also at Ely, Simon Langham in 1364 wrote: "Lay people are not to stand or sit amongst the clerks in the chancel during the celebration of divine service, unless it be done to shew respect or for some other reasonable and obvious reason; but this is allowed for the patrons of churches only."[6] Then what had been claimed successfully by those of noble birth, and by patrons in particular, was claimed with equal success by any good Churchman of consideration and wealth, especially if he were a benefactor of the church. For in the fourteenth century Alan de Alnewyk of York, goldsmith, wills that his body be buried in the quire of St Michael Belfry near the place where I used to sit ("ubi sedere solebam"). Another century later, Robert Constable of Bossall, leaves this direction in 1454: "First, I devise my soul to God Almighty and his mother Blessed Saint Mary and to Saint Botolph and to the holy court of heaven; and my body to be buried in the quire afore the place where my seat is."[7] In 1511 Robert Fabyan, the chronicler, citizen and draper of London, devises as follows: "I will that my corps be buried between my pew and the high altar, within the quire of the church of Allhallows, Theydon Gardon, Essex." Finally, at Yatton, Somerset, in 1529, 2s. was "paid for a sege in ye chaunsell."[8] It is to be remembered moreover that though it may have been unusual for laymen to have seats in the chancel, yet it was by no means uncommon for them to stand or kneel there; there are enough representations of laymen so standing to establish that point satisfactorily: they are shewn standing or kneeling, sometimes with lighted tapers in their hands. At a St Martin's mass in France in the fourteenth century,[9] two women are shewn near the altar steps, one standing and attending to her duties, the other inattentive and seriously distracting the attention of an acolyte kneeling near. We know definitely that in Salisbury cathedral laymen were allowed to be present in the sanctuary before the Sunday procession; for after the hallowing of the water it was ordered that the priest should asperge the laity in the presbytery as well as the clergy in the choir. "Post aspersionem clericorum laicos in presbiterio hinc inde stantes aspergat."[10] At Salisbury the Sunday procession was marshalled in the ample space between the choir and the high altar, which space the laity entered in order to follow the clerks in the procession.

For women it was more difficult to get admission to the chancel. Tradition and usage were against them. As early as A.D. 367 the Council of Laodicea passed a canon that women ought not to come near the altar or enter the apartment where the altar stands. In the ninth century a canon was passed at Mantes that women must not approach the altar or act as "server" to the celebrant or stand in the chancel. Among the canons of the time of King Edgar is one: "Docemus ut altari mulier non appropinquet dum Missa celebratur"; "a woman must not come near the altar at Mass." In laying down regulations for the services in Ripon Minster Archbishop Greenfield says, "We permit no women at all, religious or secular, unless great ladies or ladies of high rank or others of approved honour and piety, to sit or stand in a stall or elsewhere in the choir while the divine offices are being celebrated." "Nullas omnino mulieres, religiosas vel seculares, nec laicos nisi magnas aut nobiles personas aut alias quarum sit honestas et devocio satis nota, in stallo vel alibi in choro inter ministros ecclesiae stare vel sedere dum divina celebrantur officia permittimus."[11] The story told about Sir Thomas More shews that while he himself sat in the chancel, Lady More sat in the nave. "During his high Chancellorship one of his gentlemen, when service at the church was done, ordinarily used to come to my Lady his wife's pew-door and say unto her 'Madame, my Lord is gone.' But the next holy day after the surrender of his office of Lord Chancellor, and the departure of his gentlemen from him, he came unto my Lady his wife's pew himself, and, making a low courtesy, said unto her, 'Madam, my Lord is gone.' But she, thinking this at first to be but one of his jokes, was little moved, till he told her sadly he had given up the Great Seal." And many other good Churchmen at all times have retained the ancient usage of the exclusion of women from the stalls in the chancel. At Great Burstead, in Essex, in 1661, an applicant was authorised to build a pew at the entrance to the chancel for the use of himself and sons and companions and friends of the male sex; but to build another in the nave for his wife and her daughters and companions and friends of the female sex. King Charles I. in 1625 wrote, "For mine own particular opinion I do not think ... that Women should be allowed to sit in the chancel, which was instituted for Clerks"; and in 1633, when he visited Durham cathedral, the choir was cleared of all the seats occupied by the Mayor and Corporation and the wives of the Dean and Prebendaries and other "women of quality," and his Majesty gave orders that they should never again be erected, "that so the Quire may ever remain in its ancient beauty." Even to this day in some cathedrals it is the usage to allow women to sit only in the lower desks of the choir and not in the stalls above. Nevertheless in plenty of instances the pertinacity of women prevailed; and where the husband sat in the chancel, there the wife insisted on sitting beside him. Thus in a suit instituted by Lady Wyche in 1468, the lady put it on record that she had a seat in the chancel: "jeo aye un lieu de seer en le chauncel." In 1468 two ladies had seats in the chancel of Rotherham church; for the master of the grammar school willed that he be buried in south chancel[12] near the stall in which the wife of the Bailiff of Rotherham and the testator's wife sit. In 1553 a new pew was made for Sir Arthur D'Arcy and his wife at St Botolph, Aldgate: "Paid to Mattram, carpenter, for three elm boards for the two new pews in the quire where Sir Arthur Darsey and his wife are set ... ijs. viijd." The same parish in 1587 gave Master Dove permission to "build a pew for himself, another for his wife to sit in, being in the chancel." Therefore we come to the conclusion that at any rate from the thirteenth century onward more and more seats were provided in the chancel for lay folk. Where, as in the parish church of Boston, the stalls are very numerous—at Boston there are sixty-four—it is likely that a considerable number of them were appropriated to various important gilds connected with the church.

But there is another purpose which parochial stalls subserved, and that is the most important of all: viz., to accommodate a surpliced choir. The introduction of surpliced choirs into chancels in modern days was an innovation at first deeply resented, and seems to have been usually made in ignorance of the existence of mediæval precedent. Precedent there is, however, in abundance. England was a merry, tuneful land before the Reformation, and nowhere more than in the churches. The musical part of the service grew more and more ornate, especially in the last years immediately preceding the Dissolution; the parishes—village and town parishes alike—delighted in "the cheerful noise of organs and fiddles and anthems," and spent on music a very large part of the church income. The early years of the sixteenth century were a glorious time for church music; the parishioners loved it and would have it, and were willing to pay for it; it was not forced on them from above; it was the people and the people's churchwardens who would have it. What a joyful sound we should hear from the church doors if we could enter once more an English church of the sixteenth century and hear the surpliced men and boys a singing in the choir, accompanied by organs and citterns and fiddles and crowdes and dulcimers and all instruments of music in the rood loft, with perhaps an anthem or a solo on high festival days from distinguished vocalists of the neighbouring villages; those were happy times. Take the churchwardens' accounts of St Mary at Hill, London.[13] In this church in 1523 there was "paid 15d. for 6 round mats of wicker for the clerks." If we assume six more for the boys, we get a regular choir of six men and six boys. But besides these an extra choir of choirmen and boys was engaged for special days. In 1527 there was "paid 9d. at the Sun tavern for the drinking of Mr Colmas and others of the King's chapel that had sung in the church of St Mary at Hill." In 1553 there was "paid 16d. to the gentlemen of the Queen's chapel for singing a mass at St Mary at Hill." Again, in 1527 there was "paid 7s. for bread, ale and wine for the quire, and for strangers at divers feasts in the year past"; these "strangers" would probably be singers hired from other churches. The above entry shews that the choir was paid in kind as well as in money. The choirmen received quite handsome salaries. In 1524 Morres, the bass, was receiving from the parish 20 nobles a year. John Hobbes was the most expensive member of the choir. In 1556 there was paid to John Hobbes 56s. 8d., being one quarter's wages, for his services in the choir. This choirman therefore had a salary of £11. 6s. 8d. per annum, which would be equivalent to about £113 of our money. Sir John Parkyns, a bass, received a quarterly salary of 15s. 8d. "for the help the quire when Hobbes was dead, and to have 8d. a day every holy day and Sunday." On the other hand there was "paid 12s. to Mr Hilton, priest, for three quarters of a year, for keeping daily service in the quire in 1528"; this was at the rate of 16s. per annum; this compares remarkably with John Hobbes' salary of £11. 6s. 8d. per annum; even allowing for the fact that Mr Hilton had other sources of revenue, we cannot but infer that priests were cheap and good singers dear in the sixteenth century. The parishes were quite willing to pay for good music. At Braunton, Devon, c. 1580, i.e., after the Reformation, the churchwardens were still paying four or five expensive choirmen, as well as singing boys; the highest salary for a choirman was 26s. 8d.; say £13. 6s. 8d. per annum; the choir in this village church could not have cost the parish less than £100 per annum of our money. In all the choirs there seem to have been "singing boys" as well as men. We hear in 1477 of four choristers being brought over to St Mary at Hill for a special service, for which they received the modest sum of 1d. each. At this church it was finally arranged to have a permanent choir, and what we should call a choir school was established, with John Norfolk, the organist, at the head of it to train the boys: for there "was paid for making clean of a chamber in the Abbot's Inn to be a school for Norfolk's children." The same year "Mr parson gave the boys a playing week to make merry," and the churchwardens kindly presented the boys and choirmen with 3s. 4d. to spend on their holiday. Next year there was again a payment of 3s. 4d. "in the playing week after Christmas to disport them." Both the boys and the men wore surplices, bought at the expense of the parish. In 1496 there were at St Mary at Hill "8 surplices for the quire, of which 2 have no sleeves; and 7 rochets for children, and 6 albs for children." In 1499 there was "paid 12d. for the making of 6 rochets for children that were in the quire." At St Nicholas', Bristol, in 1521 there was paid "1d. for making a child's surplice belonging to the quire"; and in 1542 iiis. viid. for material "to make 2 lads' surplices." An inventory of Huntingfield church, Suffolk, shews that the church possessed "vii rochettys ffor men and vii for chyldern," and that the material of the rochets cost 6d. each; it would seem that this Suffolk village had seven men and seven boys in the church choir. At St Mary at Hill there was paid in 1523 "for making 12 surplices for men at 6d. each, 6s.; and for 12 surplices for children at 5d. each, 5s."; this was a rich city parish, and could afford to have a pair for each choir man and boy, one to be in use, the other at the wash. Then music had to be paid for. In the same church in 1523 there was paid "for 4 hymnals and a processioner, noted, for the clerks in the quire, 6s. 8d."; in the same year there was paid "for two quires of paper to prick songs in, 8d." In 1555 at St Mary the Great, Cambridge, there was "paid 3s. 4d. for the copy of the service in English set out by note; and 1s. 4d. for writing and noting part of it to sing on both sides of the quire"; i.e., they sang antiphonally. There are numerous entries as to the cost of the organ and of the constant repairs which it required. Lastly, there was the organist's salary, which if it was anything like the sum received by John Hobbes, would be a heavy item. An eminent organist like John Norfolk, who was in charge of a choir school, would expect and no doubt get a large salary. In village churches, however, the boys would be trained, sometimes by a chantry priest if he was under statutory obligation to do so, more often by the parish clerk. The latter was a permanent official with a freehold, as he is still, and a person of much importance and dignity. Before the Reformation, in addition to serving at the daily Mass in a village church, carrying holy water and "blessed bread" round the parish, and many other functions, he was more especially in charge of the musical part of the services. He was expected to sing or chant himself, especially the psalms; he had to read the epistles; and, at any rate in the sixteenth century, he had to train the choir boys. It was ordered at Faversham in 1506 that "the clerks, or one of them, so much as in them is, shall endeavour themselves to teach children to read and sing in the quire." And at St Giles', Reading, in 1544 there was a payment of 12s. "to Whitborne the clerk towards his wages, and he to be bound to teach 2 children for the quire."

Hambleton

Beside the professional choirmen and the parish clerks there were sometimes amateurs also giving help. Sir Thomas More used to sing in Chelsea church like any parish clerk. "God's body," said the Duke of Norfolk, coming on a time to Chelsea and finding him in Chelsea church, singing at Mass in the choir, "God's body, my Lord Chancellor, what turned parish clerk?" Put these items together—the wages of choirmen and boys, and now and then of extra help, the making, mending and washing of surplices, the cost of music, the salaries of the organist and parish clerk and the cost of the choir school, and it will be seen that the services of a large town church must have been, musically, on quite a grand scale; it is equally plain that the love of church music and the willingness to pay for it were equally great in the villages. It is not possible here to go further into this matter of the church music. It may be said briefly, however, that the plain chant of the Divine Office and of the Mass would be sung in the chancel, and that for this the permanent village choir of men and boys would suffice. Every parish that could afford it seems to have had a rood loft and an organ in it. But the organ would not be used to accompany the plain song, but for what we call "voluntaries" in the various intervals of the Mass and other services. The organ again would be employed when there was singing of "motets," i.e., anthems, whether the singers were in the choir or the rood loft. On great days when minstrels playing all manner of instruments were got together to help out the organ, they would no doubt be placed in the rood loft, with any extra vocalists for whom place could not be found in the choir below.

Chaddesden

Summing up, we may say that in a parochial chancel seats were required (1) for the parish priest, the parish clerk and any chaplains or chantry priests; (2) for the patron and a few of the leading churchfolk of the village; (3) for a choir of men and boys which was occasionally enlarged by choirmen and choristers borrowed from neighbouring churches. Altogether quite a considerable number of seats would be required; and we need not be surprised that there are so many stalls in small village churches, but rather that they are not more; no doubt, however, additional forms or benches would be introduced on days of great festival.

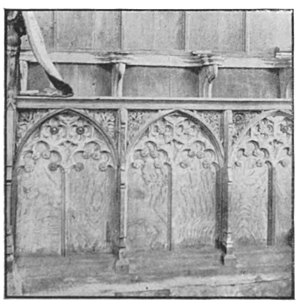

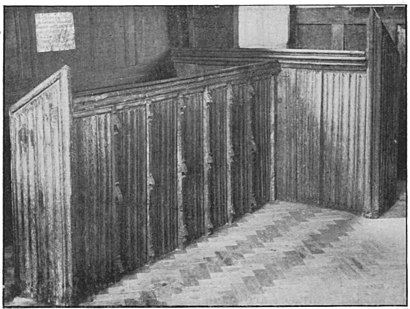

Not every parish church could afford to have a set of stalls made, cathedral fashion, for its chancel. In many cases probably the seats were but benches or settles; and the naked, desolate look of many spacious chancels is no doubt due to the removal of these seats. Desks, or as they were Latinised "deski," there must have been, at least one at each side, on which to place the anthem book, processioner and other music. We hear of a double desk at St Mary at Hill; but only the richest parishes seem to have provided desks for the choir boys as well as for the men. In poor parishes the men had not armed stalls, but merely a bench to sit on.[14] The boys sometimes had a bench; sometimes, as at Stowlangtoft, Suffolk (91), the bench was framed into the desk behind. At the back of the choirmen's seats, there might be bare wall; or it might be panelled, as at Sall, Norfolk (85), or arcaded, as at Chichester Cathedral (36). In richer examples there might be above the panelling a coved cornice, as at Stowlangtoft and Balsham, Cambridge (3). A still more sumptuous design was to erect a horizontal canopy above the stalls, as at St Peter's (89) and All Saints' (45), Hereford, and Brancepeth, John Cosin's church, Durham (93). The return stalls, facing east, would be those of the parish priest and his clerical helpers, and were often more spacious and lofty than the rest, and backed on to the screen, as at Chaddesden, Derbyshire (99), and Trunch, Norfolk (85).

The workmanship of the best stalls is quite first rate. At All Saints', Hereford, the timber of the stalls is "good sound English oak, all either cleft or cut in the quarter, proving that the trees were converted into the smallest possible sizes before being sawn from either end, the very rough saw-kerfs meeting at an angle in the centre of the board."[15] The stalls frequently stand on stone plinths, pierced for ventilation; e.g., at Sall and Trunch (85).

- ↑ These are illustrated in Archæologia Cantiana, vol. xiii.

- ↑ York Fabric Rolls, 35, 248.

- ↑ Canon Savage's pamphlet, 369.

- ↑ Cutts' Parish Priests, 466.

- ↑ Gasquet's Parish Life in Mediæval England, 96.

- ↑ Gasquet, Parish Life in Mediæval England, 45.

- ↑ It is of course possible that both Alan de Alnewyk and Robert Constable sat in the chancel in surplice either as a member of a gild or of the choir.

- ↑ This, however, may have been for one of the choirmen or choristers.

- ↑ Reproduced in Gasquet, ibid., 47, from Didron.

- ↑ Wordsworth's Salisbury Ceremonies and Processions, 20.

- ↑ Inhibitions of Archbishop William of York in 1308 and 1312 in Rev. Dr Fowler's Memorials of Ripon Minster, Surtees Society, vol. 78.

- ↑ "South chancel" may mean "the chapel south of the chancel."

- ↑ Admirably edited by Mr Littlehales for the Early English Text Society; vols. 20 and 24.

- ↑ At Hambleton (98) the chancel was remodelled, and the simple desks with linen pattern may be of that date. But the seats behind were never more than rough movable benches.—G. H. P.

- ↑ R. H. Murray on Ancient Church Fittings, 12.