User:Feydey/Panama, past and present

Panama Past and Present

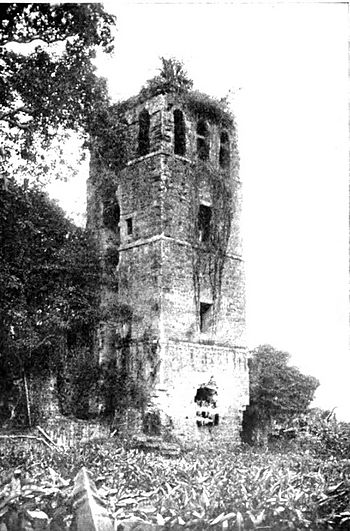

RUINS OF THE CATHEDRAL TOWER, OLD PANAMA

Panama

Past and Present

By

Farnham Bishop

New York

The Century Co.

1916

Copyright, 1913, 1916, by

The Century Co.

Published February, 1913

Revised Edition, October, 1916

DEDICATION

To the Old Admiral, white and frail,

Red Indian, swarthy Cimaroon,

Conquistadores brave in mail,

Beneath the blaze of tropic noon,

To Morgan's swaggering bucaneers,

To gallant Nuñez and his men;

To Goethals and his engineers,

Who cleft the peaks of Darien.

INTRODUCTION

IT is eminently fitting that this book should appear at the present time. No more suitable occasion for a popular treatise on the Panama Canal can be imagined than the eve of the opening of the greatest trade route known in the history of the world.

A study of this noteworthy undertaking is of especial value to us because this is an American achievement, projected by the people of the United States through their representatives at Washington; paid for from the revenues of this nation; accomplished by the grit, sagacity, and perseverance of some of the greatest Americans of this generation. We are not intelligent if we are uninformed on such a subject; we are unwise if we fail to appreciate its significance; we are unpatriotic if we do not applaud the doings of such citizens.

Clarence A. Brodeur.

State Normal School,

Westfield, Mass.

PREFACE

THIS book has been made possible by the kind assistance of many friends, to whom the author wishes to express his deepest gratitude. First and foremost, thanks are due to his father, Joseph Bucklin Bishop; who, ever since he became Secretary of the Isthmian Canal Commission, has been the official source of information for all who have either written or lectured about the Isthmus of Panama. Colonel Goethals and the men under him, from gang-foremen to divisional engineers, have been uniformly courteous and helpful. The librarians of Harvard University, the New York Historical Society, and the New York Public Library, have given every facility for historical research. Special thanks are due to the publishers of The World's Work, St. Nicholas, and the Harvard Illustrated Magazine, for permission to republish parts of articles written for them; and to Professor Kemp of Columbia University for authoritative information concerning the geologic formation of the Isthmus, and the closing of the prehistoric Straits of Panama.

It is hoped that this book will appeal to the average boy, as it is mainly about the two things that interest him most: fighting and machinery. Limitation of space has forced the omission of many interesting details: how Balboa's bloodhound, Leoncillo or the "little lion," could tell a hostile from a friendly Indian, and was entered on the muster-roll as a man-at-arms; how the aged Spanish admiral leapt into the sea to save his sailors who had been blown overboard by the explosion of a jar of gunpowder, in the fight with Ringrose's bucaneers; how a fleet of smugglers bombarded Porto Bello, to be revenged on the custom-house officers; how a Scotch soldier of fortune captured the city of Colon with a railroad train; or how an officer of the United States Navy arranged and refereed a battle between Panamanians and Colombians across the tracks of the Panama Railroad, in 1901. It would take a book many times the size of this to tell a tenth of the wonderful story of Panama.

Farnham Bishop.

CONTENTS | |||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| I |

| ||

| II |

| ||

| III |

| ||

| IV |

| ||

| V |

| ||

| VI |

| ||

| VII |

| ||

| VIII |

| ||

| IX |

| ||

| X |

| ||

| XI |

| ||

| XII |

| ||

| XIII |

| ||

| XIV |

| ||

| XV |

| ||

| XVI |

| ||

| XVII |

| ||

APPENDIX | |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

PAGE | ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| By permission of The Bancroft Company. | ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| By permission of S. S. McClure, Ltd. | ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| By permission of Doubleday, Page & Co. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| From a photograph by L. Maduro, Jr., Panama. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| By permission of Doubleday, Page & Co. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| From a photograph by Marine, Panama. | ||

|

PANAMA PAST AND PRESENT

PANAMA PAST AND

PRESENT

CHAPTER I

GEOGRAPHICAL INTRODUCTION

AHUNDRED thousand years ago, when the Gulf of Mexico extended up the Mississippi Valley to the mouth of the Ohio, and the ice-sheet covered New York, there was no need of digging a Panama Canal, for there was no Isthmus of Panama. Instead, a broad strait separated South and Central America, and connected the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. This was the strait that the early European navigators were to hunt for in vain, for long before their time it had been filled up, mainly by the lava and ashes poured into it by the volcanoes on its banks.

But though the formation of the Isthmus is for the most part volcanic, it has very few volcanoes of its own, and all of these have been extinct for untold centuries. The so-called volcano in the Gaillard Cut, about which so much was once said in the American newspapers, was nothing but a small mass of rock that had become heated in a curious and interesting way. The intense heat of the sun—thermometers have registered a hundred and twenty degrees in certain parts of the Cut at noon—caused the spontaneous combustion of a deposit of sulphur and iron pyrites or "fool's gold." The smoldering sulphur heated a small pocket of soft coal, which in turn produced heat enough to crack holes in the rock, out of which came blue sulphur smoke and steam from rain water that had dropped on this natural stove. Except that care had to be taken in planting charges of dynamite in drill-holes near by, this toy volcano had no effect whatever on the canal work, and was presently dug up by a steam-shovel, and carried away on flat-cars.

Volcanic eruptions are unknown on the Isthmus of Panama, and earthquakes are very rare. The great earthquake that devastated the neighboring republic of Costa Rica in 1910, barely rattled the windows in Panama. The last shock of any severity was felt there in 1882, when considerable damage was done to the cathedral, and to the Panama Railroad, and the inhabitants were very badly frightened. But for more than two hundred years there has been no earthquake strong enough to bring down the famous "flat arch" in the church of San Domingo, in the city of Panama. This arch, which was built at the end of the seventeenth century, has a span of over forty feet and a rise of barely two, and all the engineers that have seen it agree that only a little shaking would be needed to make it fall.

Geographically, Panama is the connecting link between South and Central America. Politically, it lies between the republic of Costa Rica and the United States of Colombia, of which it was once a part. It is a much larger country than most people realize, having a length of four hundred and twenty-five miles, and a width of from thirty-one to one hundred and eighteen miles, with an area of about thirty-three thousand, five hundred square miles, which is very nearly the size of the State of Maine. At the place where the canal is being built, the Isthmus is about forty miles wide, but though the actual distance from ocean to ocean is less in other places, the only break in the central range of mountains, the Cordilleras del Bando, that runs from one end of the country to the other, occurs at this point. At the narrowest part of the Isthmus, near the South American end, the hills are from one to two thousand feet high, while near the Central American end there are not a few peaks of from six to seven thousand feet. At the summit of the old pass at Culebra, before the engineers began to cut it down, the continental divide was only two hundred and ninety feet above sea-level.

On either side of the Cordilleras, broad stretches of jungle or open prairie slope down to the sea, the former predominating on the Atlantic side, the latter on the Pacific. Numerous streams flow into the two oceans. The largest of these is the Tuyra, which, with its tributary, the Chucunaque, empties into the Gulf of San Miguel, near the spot where Balboa waded into the Pacific (see page 61). The second largest and the best known of the rivers of Panama is the famous Chagres, whose mouth is only six miles from the Atlantic entrance of the canal. Like the Tuyra and the Chepo on the Pacific side, the Chagres is navigable for large canoes and small launches for many miles, particularly in the rainy season. River communication is very important in a heavily wooded country where roads are scarce and bad, as they were in the United States before the Revolution, and are still on the Isthmus to-day. Though most of the smaller streams are little more than creeks, they produce a great volume of water-power which may some day be utilized.

There are no lakes of any size, but there are several lagoons or natural harbors, almost completely landlocked. Chiriqui Lagoon, on the Atlantic near the Costa Rica line, has long been used as a coaling station by the United States Navy. The deep Gulf of Panama, on the Pacific, bends the greater part of the Isthmus into a semicircle.

Instead of running north and south, as you would naturally suppose, the Isthmus runs almost due east and west. That is because South America lies much farther to the east than most of us realize; so much so, that if an airship were to fly far enough in a bee line from New York to the south, it would find itself over the Pacific, off the coast of Peru. At Panama, the Pacific, instead of being west of the Atlantic, is southeast of it. That is why the Spaniards, coming overland to this new ocean from the one they had left on the north, called it the "South Sea." A glance at the map on page 4 will make this plain. It sorely puzzles the visitor to the Isthmus to find the points of the compass apparently so badly twisted, particularly when he sees the sun rise out of the Pacific and set in the Atlantic.

Though the two oceans are so near together at this point, there is a great difference in the rise and fall of their tides. The harbor of the city of Panama, on the Pacific side, where there is twenty feet of water at high tide, is nothing but a mud-flat at low tide, and the

AREA OF HEATED ROCK IN CULEBRA CUT.

Once thought to be a volcano.

townspeople walk out among the stranded boats, and hold a market there (see page 213). The tide comes rushing in, when it rises, in a great wave or bore, something like that in the Bay of Fundy, with a heavy roar that can be heard far inland on a still night. But at Colon, on the Atlantic, the rise and fall of the tide is less than two feet. This curious fact, that the tides rise and fall ten times as far on one side of the Isthmus as on the other, is doubtless what has caused the wide-spread belief that at Panama one ocean is higher than the other. People who say that, forget that the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific meet

MANGOES.

at Cape Horn, and that sea-level is sea-level the world over.

Panama is about eight hundred miles from the equator, in the same latitude as Mindanao in the Philippines. Its climate is thoroughly tropical. Gilbert, the only poet the Isthmus has ever produced, summed it up neatly in the first stanza of one of his best-known poems, "The Land of the Cocoanut Tree":

Away down South in the Tropic Zone;

North latitude nearly nine,

When the eight month's pour is past and o'er,

The sun four months doth shine;

Where it 's eighty-six the year around,

And people rarely agree;

Where the plantain grows and the hot wind blows,

Lies the Land of the Cocoanut Tree.

"Eighty-six the year around" may seem an underestimate but, as a matter of fact, the mercury stays very close to that point from year's end to year's end, seldom rising above ninety. (The temperature of a hundred and twenty, spoken of on page 3, was only found in the deepest parts of the Gaillard Cut at noon.) At night it is always cool enough to necessitate a light covering, and never so hot that one cannot sleep, as it too often is in a Northern summer. It is always summer in Panama, and no hotter in August than in December. Snow-storms and cold weather are, of course, unknown, though three times since the Americans established a weather bureau on the Isthmus it has recorded brief local showers of hail.

Instead of four seasons, there are two: the rainy and the dry. From April to the end of November it rains very frequently, not every day, as is sometimes declared, but often enough and hard enough to fill, in those nine months, a tank from twelve to fifteen feet deep. With so much rain, and an ocean on either hand, the dampness and humidity are very great. Mold gathers on belts and shoes; guns and razors become rusty unless coated with oil; books must not be left outside air-tight glass cases or they will fall to pieces; and every sunshiny day the clothes closets are emptied and the garments hung out to air.

At that time of year it is easy to realize why houses on the Isthmus are built up in the air on concrete legs; and

CULEBRA CUT, LOOKING NORTH

When completed, the bottom of the canal will be forty-five feet

below the level shown in this picture.

the morning paper announces that the Chagres River has risen forty feet in two days and is still rising. The rainfall is much heavier on the Atlantic side than the Pacific. They have a saying at Colon that there are two seasons on the Isthmus, the wet and the rainy; and the people of that town used to boast that it rained there every day in the year. But their local pride had a sad fall at the end of the record dry season of 1912. At Colon, as well as elsewhere, it had not rained for months, wide cracks had opened in the hard, dry ground, and the whole country-side was as brown and ragged as an old cigar. When at last "the rains broke" at Ancon, over on the Pacific side, in a magnificent cloudburst—six solid inches of water in three hours—they were still carrying drinking-water to Colon in barges, and had to borrow Ancon's new motor fire-engine to pump it through the mains.

When the rains have come, it is a wonderful sight to see how quickly the old, half-dead vegetation disappears, and the new green stuff comes rushing up. Though the soil is not rich, the heat and moisture cause plants to grow with incredible speed and rankness. Fence-posts sprout and become young trees. The stone-ballasted roadbed of the Panama Railroad has to be sprayed twice a month with crude oil to keep down the weeds. On either side of the track for the greater part of the way across the Isthmus stretches unbroken jungle, rising like a wall at the edge of the cuttings, or lying like a great, green sea below the embankments. It is a thoroughly satisfactory jungle, every bit as good as the pictures in the school geographies. High above the rest tower the tall ceiba trees, great soft woods larger than the largest oak. Besides these and the native cedars, there are mahogany, lignum-vitæ, coco-bolo, and other hardwoods. Some of these are exported for lumber, others the natives hollow out into canoes, some of which are of incredible size. I have seen a dugout, made from one gigantic tree trunk, so large that it was decked over and rigged as a two-masted schooner.

Under the trees, the ground is clogged with dense masses of tangled undergrowth, bound together with thorny creepers, and the rope-like tendrils of the liana vine. Worst of all to travel through are the mangrove

MAN O' WARSMAN.

swamps near the sea, for the branches of these bushes bend down to the ground and take root, so that it is like trying to walk through a wilderness of croquet wickets. Both here and in the jungle, a path must be cut with the machete, a straight, broad-bladed knife between three and four feet long, that is the great tool and weapon of tropical America. A skilled machatero, or wielder of the machete, can cut a trail through the jungle as fast as he cares to walk down it.

The great tree of Panama is the palm. There are

THE FLAT ARCH IN THE RUINS OF SAN DOMINGO CHURCH, PANAMA CITY

said to be one hundred different species on the Isthmus. Most beautiful of all is the stately royal palm, brought by the French from Cuba to fill the parks and line the avenues. More useful is the native cocoanut palm, that grows everywhere, both in and out of cultivation. Several million cocoanuts are exported from the Isthmus every year. The brown, fuzzy shell of the cocoanut, as we know it in the grocery store at home, is only the innermost husk. As it grows on the tree, the cocoanut is as big as a football, and as smooth and green as an olive. Cut through the thick husk of a green cocoanut with a machete, and you have a pint or more of a thin, milky liquid that is one of the best thirst-quenchers in the world. When the nut is ripe the husk falls off and the milk solidifies into hard, white meat. When this is cut up into small pieces and covered with a little warm water, a thick, rich cream will rise, which cannot be distinguished from the finest cow's cream. Ice cream and custards can be made from this cream, and they will not have the slightest flavor of cocoanut. If, however, this cocoanut cream is churned, it will turn into cocoanut butter, which is good for sunburn, but not for the table. The nuts of the vegetable ivory palm are shipped to the United States to be cut up into imitation ivory collar-buttons.

A native Panamanian will take his machete, cut down and shred a number of palm-branches, and with them thatch the roof of his mud-floored hut, which is built of bamboos bound together with natural cords of liana. Then with the same useful instrument he will scratch the ground and plant a few bananas, plantains—big coarse bananas that are eaten fried—and yams—a sort of sweet potato—and they will take care of themselves until he is ready to harvest the crop. He can burn enough charcoal to cook his dinner, and gather and sell enough cocoanuts to buy the few yards of cloth needed to clothe himself and his family, and spend the rest on hound dogs, fighting-cocks, and lottery tickets. He can grow his own tobacco, and distill his own sugar-cane rum. Now that the Americans have put an end to the revolutions, the poor man on the Isthmus has not a care in the world, and is probably the laziest and happiest person on earth.

Besides bananas—which, by the way, grow the other way up from the way they hang by the door of the grocery—many different kinds of fruit are found in Panama. Mangoes and alligator-pears are great favorites with American visitors. On the Island of Taboga, in the Bay of Panama, grow some of the best pineapples in the world; not the little woody things we know in the North, but luscious big lumps of sugary pulp, soft enough to eat with a spoon. You have never tasted a pineapple until you have eaten a "Taboga pine."

Flowers are as abundant as fruit. There are whole trees full of gorgeous blossoms at certain seasons. Roses bloom during the greater part of the year and rare and valuable orchids abound in the jungle. If the Republic of Panama ever adopts a national flower, it should be that strange and beautiful orchid found only on the Isthmus, that the Spaniards called "El Espiritu Santo," the flower of the Holy Ghost. When it blooms, which it does only every other year, the petals fold

THE "HOLY GHOST ORCHID."

back, revealing the perfectly formed figure of a tiny dove.

It is true that the flowers on the Isthmus have no perfume, but it does not follow, as is so frequently declared, that the birds of Panama have no song. I have often heard them in the mating season, at the beginning of the rains, chirping and twittering as gaily as any birds in the Northern woods. Most conspicuous of all, among the feathered folk of the Isthmus, are the great black buzzards and "men-o' warsmen," so named because they wheel about over the city in large flocks, manœuvering with the precision of a squadron of battleships. Formerly, these birds were the only scavengers, all refuse being thrown out into the street for them to eat. They will soar and circle for many minutes with hardly a beat of their broad wings. When the first aeroplane (a small Moissant monoplane), came to Panama and flew among a flock of buzzards, it was difficult for a man on the ground to tell the machine from the birds. Other large fliers are the pelicans, while tall, dignified blue herons and white cranes walk mincingly through the swamps. Parrots of all sizes abound, from big gaudy macaws, with beaks like tinsmiths' shears, to dainty little green parrakeets, that the engineers call "working-models of parrots." Tiniest and loveliest of all are the bright-colored humming-birds.

There are not many large mammals native to the Isthmus, and most of these have been hunted until they are now hard to find. The last time that a "lion," as the natives call the jaguar—a black or dark-brown member of the cat tribe, as big as a St. Bernard dog—was seen in the city of Panama, it was brought there in a cage and advertised to appear in a ferocious "bull and lion fight," at the bull-ring. When the cage door was opened in the ring, the jaguar jumped over the tenfoot barricade into the audience, bounded up the nearest aisle to the top of the grandstand, leaped down, and was last seen heading for the jungle. No one was hurt, for everybody gave him plenty of room. Another much-advertised beast that is seldom seen is the tapir, a fat black grass-eater, that looks like a miniature elephant with a very short trunk. Deer are still fairly abundant, pretty little things, not much bigger than a North American jack-rabbit. Centuries ago there were large numbers of warrees, or wild hogs, and of long-tailed, black-and-white monkeys, "the ugliest I ever saw," wrote Captain Dampier, the bucaneer naturalist. But to shoot either of these to-day, a hunter would have to

ARMADILLO.

go deep into the jungle. Perhaps the most curious-looking animal on the Isthmus is the armadillo, "the little armored one," the Spaniards called him, because of the heavy rings of natural plate-mail that protect him against the teeth and claws of his enemies, as do the quills of the Northern porcupine.

Reptiles are well represented on the Isthmus, though snakes are very much scarcer in the Canal Zone than one would naturally suppose. Only a few small boa-constrictors—eight feet long or so—were killed during the building of the Canal, and there is no case of a laborer having been fatally bitten by a poisonous snake, although both the coral-snake and the fer-de-lance are said to be found in Panama. Old stone ruins, that in the North would be swarming with blacksnakes and adders, seem here to be entirely given over to the lizards. Lizards are everywhere, and of all sizes, from three

IGUANA.

inches long to five or six feet. These big fellows are called iguanas, and look remarkably like dragons out of a fairy-book, except that they have no wings and do not breathe fire and smoke. They are quite harmless, and eagerly hunted by the natives, because their flesh, when well stewed, tastes like chicken. One of the old chroniclers speaks of these lizards as "'guanas, which make good broth."

CROCODILE.

BRIDGE AT THE ENTRANCE TO OLD PANAMA

Over three hundred years old.

is larger and much more ferocious, and has a longer and sharper head. Many a man who has been upset in a canoe on the Chagres, or who has walked too near what looked like a rotting log stranded on the bank, has been caught and eaten by a crocodile. Parties of Americans are often organized to hunt and kill these dangerous reptiles.

Man-eating sharks are found in the waters on either side of the Isthmus, as well as an abundance of Spanish mackerel, and other food fish. Indeed, the name "Panama" means, in the old Indian tongue, "a place abounding in fish." There is not much chance that the different breeds of the two oceans will have a chance to mingle by swimming through the canal, unless they are able to swim uphill through locks and sluices, and through a fresh-water lake. (See page 230.)

Though men and other animals are sluggish and lazy in the tropics, it is there that insects show the greatest vitality and activity. The big black ants go marching about at night in small armies, and negroes are hired to follow them till they find their nests, which they then pour full of an explosive liquid and blow up. Well-defined ant trails, an inch or so wide, run through the jungle, and even at noon they are crowded with hurrying passengers, every fourth or fifth ant carrying a bit of green leaf by way of a parasol. A corner of a cinder tennis court that was built for the officers of the battalion of marines at Camp Elliott blocked one of these ant paths, and the ants kept cutting it down to the former level, no matter how often the soldiers filled it up. Little red ants swarm in all the houses, however well they are kept. Sugar, candy, and all other sweet things are only safe on top of inverted tumblers standing in bowls of water, for nothing short of a moat will keep out the ants. But at the same time, this stagnant water may be serving as a breeding-place for mosquitoes. There used to be over forty different kinds of mosquitos on the Isthmus, but nowadays they are very rare.

Another insect pest, however, that has not been abated is the famous "red bug," a tiny tick, smaller than the head of a pin, but big enough to make plenty of trouble. The red bugs live in the grass, and burrow under the skin of human beings and animals and breed there until they are dug out with the point of a knife. Other species of ticks attack horses, cattle and fowls, and are a great pest to farmers in that country. Compared to them the more picturesque and widely feared scorpions and tarantulas do almost no harm. Both the scorpion, who looks like a small lobster with his tail bent up over his head and a sting at the end of it, and the tarantula, a huge spider covered with stiff black hair, are hideously ugly, and their bite or sting is intensely painful. But it is not fatal, as is commonly and erroneously supposed, and for every man that is hurt by a scorpion or tarantula, hundreds of dollars' worth of damage is done by ticks and red bugs.

Before the white men came, there was a large native population on the Isthmus. Some of the Spanish chroniclers place the number of Indians as high as two millions; almost certainly there were more of them than the three hundred and fifty thousand persons, of all races (see page 244), that inhabit that country to-day. The life of the early Indian was not unlike that of the poorer Panamanian of the present. He wore less clothing and his women made it of cocoanut fiber instead of imported cotton cloth; instead of a steel machete he used a sort of hardwood sword called a macana,[1] and he hunted and fought with bow and spear instead of firearms. But the

SAN BLAS INDIANS IN VARIOUS COSTUMES.

bohio or thatched hut, the cayuca or dug-out canoe, the rude farming and the fishing, have scarcely changed at all. The Isthmian Indians are very skilful boatmen and fishermen. Their canoes are often seen in Colon harbor, where they come to sell their catch. These Indians belong to the Tule or San Blas tribe, that occupy and rule the Atlantic side of the Isthmus, from about forty miles east of Colon to South America. The Pacific side of this part of Panama is held by another tribe of Indians, the Chucunaques. Both pride themselves on keeping their race pure, despise the mongrel, half-breed Panamanians, and forbid white men to settle in their country. People who complain that the San Blas and the Chucunaques are "treacherous," and "inhospitable" forget that they are the survivors of a race once hunted down

SAN BLAS INDIAN SQUAWS.

Sitting with American canal employees on a dug-out canoe in a San Blas coast town.

White men are not allowed ashore after sundown.

by the white men with fire and sword and bloodhounds for their gold. In appearance, the San Blas are short, stocky, little fellows, many of them looking remarkably like Japanese.

The narrowest part of the Isthmus is in the San Blas country, and has long been a favorite among the many proposed routes for an interoceanic canal. To give anything like a complete list of the various canal routes would be to review most of the history of the discovery

PART OF THE CHARGES RIVER.

Now in the bed of Gatun Lake, with its banks cut down to make a five hundred foot channel.

and exploration of America. From the Straits of Magellan to Hudson's Bay, the early navigators sought for an open passage between the two oceans. Later, whenever explorers or engineers found a place where the continent was narrow, or broken by large rivers, or lakes, proposals were made for an artificial waterway. From the middle of the sixteenth century to the end of the nineteenth, the routes most favored were the five marked by letters on the map on page 33.

A. The Darien or Atrato River route. The distance between the headwaters of the Darien River, flowing into the Gulf of Uraba, and the source of the nearest small river running into the Pacific, is very short. Canoes could be easily carried from one stream to another. There is a story that a village priest, at the end of the eighteenth century, had his parishioners dig a ditch, so that loaded canoes could be floated across the divide, without a portage. Whether or not that is so, it would be impossible for even the smallest modern cargo-boat to steam up a mountain creek, through such a ditch, and down the rock-strewn rapids of the upper Atrato. The divide is too high and the supply of water too scanty at this point for the construction of a ship canal suited for twentieth-century commerce.

B. The San Blas route. Here, where the distance from sea to sea is only about thirty miles, Balboa crossed to the Pacific in 1513. Shortly afterwards, this country was abandoned to the Indians, except for a brief time in 1788, when an attempt was made to establish a line of posts, and a Spanish officer succeeded in crossing to the Pacific, but was not allowed to return. Interest in this region was revived by the lying reports of two adventurers, Cullen and Gisborne, who declared that they had easily crossed and recrossed the San Blas country, and found the summit-level of the divide only a hundred and fifty feet high. Induced by these falsehoods (Cullen had never been to the Isthmus, and Gisborne not more than six miles inland), a small expedition under Lieutenant Strain, U.S.N., started from Caledonia Bay, on the Atlantic side, to march to the Gulf of San Miguel on the Pacific, in January, 1854. After suffering fearful hardships and losing one-third of their number from starvation, Lieutenant Strain and the others succeeded in reaching their goal. They were followed, in 1870-1, by several strong and well-equipped naval expeditions, whose surveys proved that the summit-level is at least a thousand feet above the sea. It was then proposed to build a canal there by boring a great tunnel through the mountains; but the rapidly increasing size of ships has made this out of the question.

C. The Panama or Chagres River route. There is no truth in the story that Columbus sailed up the Chagres River and so came within twelve miles of the Pacific; but the Spaniards soon found out that the easiest way across the Isthmus was to pole or paddle up this river, and then go by road to the Pacific. The first proposal for digging a Panama canal: a shallow ditch between the head of navigation on the Chagres and the South Sea, was made as early as 1529. The Emperor Charles V not only opposed this project, but even forbade its being brought forward again, under penalty of death; ostensibly because of the impiety of the idea of joining two oceans that God had put asunder, but, really, because such a canal would give the enemies of Spain too easy access to her Pacific colonies. The later history of the Chagres route occupies the greater part of this book.

A Atrato River route.

B San Blas route.

C Panama route.

D Nicaragua route.

E Tehuantepec route.

MAP OF FIVE CANAL ROUTES.

D. The Nicaragua route. The broad surface of Lake Nicaragua, and the San Juan River, that flows out of it into the Atlantic, make this seem a most obvious place for an interoceanic canal. Though much dredging of channels and building of breakwaters would be needed to make a safe harbor at either end, and expensive locks and dams would have to be built before large steamers could navigate the river and the lake, the same disadvantages had to be overcome at Panama. The greater length of a canal at Nicaragua,—the continent at this point is one hundred and fifty miles wide,—and the closer proximity of more or less active volcanoes, with the greater danger of eruptional earthquakes, would make it inferior to the canal at Panama. The continual revolutions and political disturbances of Nicaragua, which has been so badly governed that no foreign government or private company has been willing to risk the investment of the hundreds of million of dollars needed to build a canal there, finally turned the scale against that country. Nicaragua is probably the only other place, beside Panama, where it would be physically possible to build a modern ship canal across the American continent.

E. The Tehuantepec route. Not long after the Spaniards, under Cortez, had conquered Mexico, they built a road across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, which is the narrowest part of that country. Centuries ago, there was more than a little trade by this road, between Spain and Mexico and the Far East, as was proved by the discovery at Vera Cruz of two large bronze cannon bearing the stamp of the old Manila foundry. The Isthmus of Tehuantepec is too wide and the summit-level too high, to be pierced by a sea-level canal; and the supply of water is too scanty for a canal with locks. When the French were trying to dig a canal at Panama, an American engineer, Captain Eads, proposed to build across Tehuantepec a "ship-railway": a railroad with a very broad gage, on which huge flat-cars would carry the largest vessels of the time from ocean to ocean. Like the Darien ship-tunnel, the increasing size of ships made this ingenious project impossible. The present

CROSS-SECTION OF PROPOSED SHIP TUNNEL,

SAN BLAS ROUTE.

Tehuantepec Railroad is a standard gage road, doing a thriving business in carrying transcontinental freight. This has been temporarily, if not permanently, reduced by the opening of the Panama Canal.

CHAPTER II

HOW COLUMBUS SOUGHT FOR THE STRAIT

IF you go to Panama by ship from one of our Atlantic ports, the first land you will see is Watling's Island, or San Salvador, where Columbus caught his first glimpse of the New World in 1492. We know that this is one of the Bahamas, but Columbus died in the belief that it was an island off the coast of Asia. For though he rightly supposed the world to be round so that by sailing long enough to the west you could reach the east, neither he nor any one else in Europe at the time realized how long a voyage that would be. And the last thing Columbus imagined was that he should find a whole New World.

According to his calculations, Japan must lie just about where he found Cuba, and so Columbus told his crew, and made them all take oath that Cuba was Japan. Now, he reasoned, it could be only a little distance further to the rich cities and kingdoms of the Far East. Wonderful stories of their wealth and luxury had been brought back to Europe by Marco Polo, the Venetian, and other travelers, who had made the long difficult journey overland from Europe to India, or even China. And for countless centuries the silks and spices, the gold and jewels, of the East had been carried to the West over caravan-trails that were trodden deep before the first Pharaoh ruled in Egypt. Do you know why they have the same fairy stories and folk-lore in Ireland that they have in Japan? Because they passed from lip to lip, from camp-fire to camp-fire along this old trade-route, no one knows how many thousand years ago.

STATUE OF COLUMBUS AT MADRID.

But in the fifteenth century the Turks captured Constantinople and closed the overland road. This threw the whole world out of gear. The Portuguese were the first to look for a new way to India, by sailing round Africa. And in 1487, the brave captain, Bartholomew Diaz, succeeded in rounding the "Cape of Storms," and came back with the news that he had entered the Indian Ocean, and that there was good hope of reaching India by that route. So the King of Portugal commanded the "Cape of Storms" to be rechristened the "Cape of Good Hope," and so it is called to this day.

Bartholomew Columbus was on this voyage and talked it over with his brother Christopher, who pointed out how much easier and shorter it would be to sail twenty-five hundred or perhaps three thousand miles straight across the Atlantic to Asia, than to make the long trip of more than twelve thousand miles round Africa. The idea was not new, but the king of Portugal would have none of it; and you know what a bitter, weary time Columbus had at the court of Spain. All these black memories must have seemed to fade like small clouds far astern, as he sailed back to Palos with the glad news that he had discovered the outposts of Asia, and that another voyage or two would surely open the direct passage to the East Indies. But more than four hundred and twenty years were to pass before that passage was to be opened.

Columbus discovered more islands on his second voyage, and on the third came to the mainland of South America, at the mouth of the Orinoco. So great a body of fresh water as here poured into the ocean could flow from no mere island but from a continent, "a Terra Firma, of vast extent, of which until this day nothing has been known."

This made one mainland, or "firm land," as the Spaniards called it, from some idea that a continent must be made of solider stuff than an island; and north of it, Cuba must make another. For at this time no one had sailed round, and this island Cuba or "Japan" was supposed to be part of the mainland of Asia. Somewhere between these two bodies of land, thought Columbus, must be a strait through which flowed the waters of the Atlantic into the Indian Ocean, causing the strong current to the west that was felt as far north as Santo Domingo. Once through the strait, instead of tamely retracing his course, he would sail round the world, and home to Spain by way of the Cape of Good Hope. By this he hoped to eclipse the success of Vasco de Gama,

CHORRERA, A TYPICAL TOWN IN THE INTERIOR OF THE REPUBLIC OF PANAMA.

who had at last realized the "good hope" of reaching India by way of the Cape, and returned to Portugal, laden with glory and riches in 1499.

It was now 1502, ten years after the discovery of America, when Columbus sailed on his fourth and last voyage. He had four ships, the Capitana, Santiago de Palos, Gallego, and Biscaina. The largest of these was but of seventy tons burden, the smallest of fifty, and all were worn and old. The crews numbered a hundred and fifty men and boys, there were provisions for two years, and both cannon and trinkets for winning gold from the Indians. Bartholomew Columbus was captain of one of the caravels, with the title of Adelantado, and with his father on the flagship was Christopher Columbus's thirteen-year-old son, Ferdinand. When he grew up, Ferdinand Columbus wrote a biography of his father, containing the best account we have of this voyage.

They sailed from Cadiz on the ninth of May, 1502, took on wood and water at the Canaries, and put in at Santo Domingo, to exchange one of the ships for another, "because it was a bad sailer, and, besides, could carry no sail, but the side would lie almost under water." But Ovando, the governor of the Spanish colony there, was an enemy of Columbus, and refused to let him have a new ship, or even to take refuge in the harbor from a threatening storm. Ovando himself was just setting forth for Spain, in a great fleet of his own, laden with much gold that had been cruelly wrung from the poor Indians, including one nugget so large that the Spaniards had used it for a table. Columbus warned Ovando that a storm was coming, and was laughed at for his pains. But scarcely had the governor's fleet set sail, when down upon it swooped a terrible West Indian hurricane, and sent most of the ships to the bottom, big nugget and all. One ship, the poorest of the fleet, reached Spain, with some of Columbus's own goods on board. On one of the few vessels that struggled back to Santo Domingo was Rodrigo de Bastidas, of whom we shall hear more presently.

Columbus's own little squadron weathered the storm, thanks to the admiral's seamanship, which to the Spanish sailors appeared "art magic." Steering once more in the direction of the supposed strait, they were carried by the currents to the south of Cuba. There they fell in near the Isle of Pines, with a great canoe "of eight feet beam, and as long as a Spanish galley." Its owner, a

CARAVEL.

cacique of Yucatan, was on a trading voyage, with a cargo of copper hatchets and cups, cloaks and tunics of dyed cotton, daggers and wooden swords edged with obsidian glass, and, strangest of all to the eyes of the Spaniards, a supply of cacao (chocolate) beans. Here was evidence of something far superior to the naked savagery of the islands. It began to look as if Columbus would have some use for the Arabic interpreters he had brought with him, together with letters to the Great Khan of Tartary.

And indeed, if the old Indian that the admiral took on board for a guide had piloted the Spaniards to his own country, they would have found there great cities and stone temples and hoards of gold to their hearts' content. But when they had come to Cape Honduras, where the shore of Central America runs east and west, they asked the old Indian which way the gold came from. He pointed to the east, away from his own country, and so Yucatan and Mexico were left to be conquered by Cortez in 1517.

Fighting against head winds—once they made but sixty leagues in seventy days—the little fleet struggled on down the coast. The first Indians they met with had such large holes bored in their ears that the Spaniards called that region "the Coast of the Ear." Better weather came after rounding Cape Gracias à Dios, or "Thanks to God," and the Indians offered to trade with guanin, a mixture of gold and copper. Pure gold, they said, was to be found further down the coast. So Columbus kept on, past what are now Nicaragua and Costa Rica, until he came to the great Chiriqui Lagoon. Here were plenty of gold ornaments, in the form of eagles, frogs, or other creatures, such as are dug up to-day from the ancient Indian graves in the Province of Chiriqui. Among them we often find little bells of pure gold, shaped exactly like our sleigh bells, but Columbus does not mention them. Ferdinand Columbus does speak of finding something a little further down the coast that seems even stranger: the ruins of a stone wall, a piece of which they brought away "as a memorial of that antiquity."

The strait was now reported to be near at hand, so the interpreters declared; just beyond a country called Veragua, rich in gold. Eagerly they sped on, passing Veragua with a fair wind that carried them by Limon Bay, where we are now digging the Atlantic entrance of the strait they sought.[2]

The admiral put in at a land-locked, natural harbor, so beautiful that he called it Porto Bello, by which name it has been known ever since. After a week's rest here he pushed on to a number of islands full of wild corn, which he called the Port of Provisions. Finally, on the twenty-fourth of November, he made his furthest harbor, a forgotten little cove named El Retrete, or the Closet.

Here the search for the strait ended. Another white man had been over the ground beyond this, Bastidas, who had escaped from the hurricane at Santo Domingo, and almost certainly met Columbus there. From the Orinoco to Cape Honduras no break had been found in the barrier between the two oceans. So they turned back, battered by storms and terrified by a great waterspout, which, says Ferdinand Columbus, they dissolved by reciting the Gospel of St. John. In Veragua they tried gold-hunting, and attempted to found a colony, but the Indians, under a crafty cacique, rose against them. After hard fighting, and an Odyssey of misfortunes, the Spaniards were forced to flee. They left the hulk of the Gallego, behind them and the Biscaina at Porto Bello. The two remaining caravels, bored through and through by the teredo worm,

RUINS AT PORTO BELLO

Probably old Spanish custom house

staggered as far as the coast of Jamaica, to be beached there, side by side. Two rotting wrecks, and the barren title of "Duke of Veragua," by which his descendants are known to this day, were all that Christopher Columbus brought back from the Isthmus of Panama.

CHAPTER III

HOW THE SPANIARDS SETTLED IN DARIEN

COLUMBUS having reported that there was gold in Veragna, the King of Spain decided to found a colony there, and another beyond the Gulf of Uraba, where Bastidas had found pearls and gold. Into this gulf flowed a river so great that it filled the bay with fresh water at low tide. This river, which is now called the Atrato, was then called the Darien, and it has given that name to all the South American end of the Isthmus.

Christopher Columbus died, a broken-hearted old man, in 1506, but his brother Bartholomew, the Adelantado, was alive and anxious to colonize the "Dukedom" of Veragua. But Queen Isabella, their patron, was also dead, and the greedy King Ferdinand was jealous of their family, and wanted these new gold-fields for the crown. So he appointed a court favorite, Diego de Nicuesa, to be governor of all the land between Cape Gracias à Dios, and the Gulf of Uraba. This was made the province of Castilla del Oro, or Golden Castille.

The poorer land east and south of the gulf was called Nueva Andalucia (New Andalusia) and given to Alonso de Ojeda, a bold explorer, the first to have followed Columbus to the New World. On that voyage, in 1499, Ojeda had had with him the Florentine merchant's clerk, Americus Vespucius, who has given his name to the whole New World.

Both the new governors were small men, well built and in the prime of life. Ojeda was a famous athlete, who had once, by way of showing his prowess before the Queen, gone out on a narrow piece of timber that projected twenty feet from the

Born at Florence, Italy, in 1452; entered commercial service in Spain; accompanied four expeditions to the New World, on the first of which, in 1497, he claimed to have reached the continent of America before the Cabots and Columbus; died at Seville in 1512.

top of the Giralda tower at Seville, "walked along it as fast as if it had been a brick floor, and at the end of the plank lifted one foot in the air, turned, and walked back as quickly. Then he went to the bottom of the tower, placed one foot against the wall, and threw an orange to the top, a height of two hundred and fifty feet."[3] He was a rough, reckless, bull-headed fighter. Nicuesa, on the contrary, was of noble descent and polished manners, a skilled musician and orator, and a great favorite at court. Both alike were lacking in the thing most essential in a leader, the power of managing men.

Both expeditions sailed from Santo Domingo. Ojeda got away first, on the tenth of November, 1509, with two ships, two brigantines, three hundred men and twelve mares. Nicuesa, the wealthier of the two, had spent all his money and more in equipping a larger fleet, and just as he was getting into his boat, he was arrested for debt. After ten days' delay a friend advanced the money, and Nicuesa set sail with two large ships, a caravel, and two brigantines, carrying a force of six hundred and fifty men.

Ojeda, in the meanwhile, had reached the harbor where the present city of Cartagena was founded in 1531. In spite of the warning of his second in command, old Juan de la Cosa, that the Indians hereabouts were hard fighters and used poisoned arrows, Ojeda landed with seventy men, and attacked one of their towns. The Indians fled, Ojeda allowed his men to scatter in pursuit, and the Indians, suddenly rallying, killed with their darts and poisoned arrows, every Spaniard of the party but Ojeda and one follower. Ojeda's great strength enabled him to break through, and his small size made it possible for him to hide well behind his shield. Indeed, when his other men found him, half dead with exhaustion but unwounded, there were the marks of three hundred arrows on it.

Nicuesa's fleet came sailing by, and he gladly lent his aid, particularly to avenge the death of Juan de la Cosa, who was one of the ambushed party and had been an old and beloved pilot of Columbus. The two governors fell on the Indians at night with four hundred men, and slaughtered a great number. Then Nicuesa sailed away to Veragua, and Ojeda entered the Gulf of Uraba and founded a town on his side of it, calling it San Sebastian.

But here there were only more poisoned arrows, and neither gold nor provisions. A ship load of food bought from a gang of pirates who had stolen it, kept the colony alive for a while. When this was gone, Ojeda sailed on the pirate craft to bring help from Santo Domingo. He left San Sebastian in charge of his lieutenant, Francisco Pizarro, of whom history had a great deal more to say. If Ojeda did not return at the end of fifty days, they were to take the two brigantines and go where they pleased.

When the fifty days were up, Ojeda and such of the pirates as were yet alive were struggling along, up to their armpits in mud, through mangrove swamps on the coast of Cuba, where they had been shipwrecked. When at last they were rescued by the Governor of Jamaica and brought to Santo Domingo (where the pirates were all hanged), Ojeda was a ruined and worn-out man. Like many another fighter of that brave, cruel age, he became a monk shortly before his death, "making," in the words of the historian Oviedo, "a more praiseworthy end than other captains in these parts have done."

Pizarro and his men waited the fifty days and a little longer, for the two brigantines would not hold them all. After enough had died of starvation and arrow-poison to make room for the rest, they sailed to Carthagena, losing one brigantine by the way. In the harbor they found reinforcements from Santo Domingo, commanded by a lawyer named Enciso, who held office under Governor Ojeda. He had with him one hundred and fifty men, with horses, arms, powder and provisions. But the most important part of his cargo was a barrel with a man in it.

This man was Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, who had made a failure of farming on Santo Domingo, and since debtors were not allowed to leave the island, had had a friend smuggle him aboard in this fashion.[4] When the cask had been opened, early in the voyage, the indignant Enciso was for setting him ashore on a desert island, but was persuaded not to do so. Now the pedantic lawyer turned on Pizarro's starving wretches, accused them of desertion, and insisted on their going back with him to San Sebastian. On the way, they were all shipwrecked again, and when they arrived at their destination they found the fort and settlement utterly destroyed, the Indians fiercer than ever, and no food. What was to be done?

Balboa showed the way. He had sailed this way before, with Bastidas, and across the gulf they had found both food and gold, on the shores of the river Darien. Most important of all, the Indians there used no poisoned arrows.

At once Enciso and Balboa, with a hundred men-at-arms, crossed to the western shore, where five hundred warriors were drawn up to meet them. Kneeling devoutly on the beach, the Spaniards vowed that if victorious they would dedicate both the spoils and their first settlement to the shrine, much reverenced in Seville, of Santa Maria de la Antigua. Then, rising, they rushed like starving wolves on the Indians. There was no poison in their arrows, and those that were not cut down in the first charge fled at once.

Provisions and gold were found in the Indian town, San Sebastian was abandoned, and Enciso founded the

OLD SPANISH PORT AT PORTO BELLO

town of Santa Maria de la Antigua de Darien. But it was another thing to rule the rough men that lived there. They had had enough of Enciso's ways, which were better suited for a law court than a frontier, and Balboa

"NOMBRE DE DIOS"—STREET SCENE.

showed them how to get rid of him. They were now on the western side of the gulf, in Nicuesa's territory, and no one claiming authority under Ojeda had any power there. Balboa was a real leader of men, Enciso was not. The lawyer was deposed and Nicuesa invited to come and rule them.

But what had become of Nicuesa? His fleet had been wrecked on the shore of Veragua, and he and the other survivors had struggled down the coast, sometimes afloat, sometimes wading through the swamps, always suffering incredible hardships. At last they came to Porto Bello, where one who had sailed with the "old admiral," as the Spaniards of that time called Columbus, recognized the anchor of the Biscaina. But the Indians killed twenty of them, and the rest fled to another port further east. "In God's name" (or, in Spanish, en nombre de Dios), cried the first man who stepped ashore, "let us stay here." And for that reason "Nombre de Dios" has been the name of that port ever since.

Of the six hundred and fifty men who had left Santo Domingo with Nicuesa, only a hundred reached Nombre de Dios, thirty of these soon died, the rest were so weak with hunger they could scarcely lift their weapons, and there was not one left strong enough to act as sentinel. Imagine their joy when a caravel came from the east, bringing Nicuesa's lieutenant, Colmenares, with supplies. He found the once handsome and elegant Nicuesa "of all living men the most unfortunate, in a manner dried up with extreme hunger, filthy and horrible to behold"; informed him of the new settlement at Antigua, and that he had been elected its governor.

This sudden change of fortune was too much for the poor little courtier. Instead of showing any gratitude, he declared that these men of Ojeda's had no right to settle in his country and that he would take away all the gold they had collected there. This news got to Antigua before him, and he was met at the beach by an armed mob. Balboa tried his best to save him, but in vain. They thrust the unfortunate Nicuesa and the seventeen men still faithful to him into a wretched, leaky brigantine, and turned him adrift to perish. And perish he did, though whether by land or sea no man can say.

So both the royal governors were gone, and Balboa the stowaway ruled in Darien.

CHAPTER IV

HOW NUNEZ DE BALBOA FOUND THE SOUTH SEA

THE first thing Balboa did, after Nicuesa had been thrust forth to die, on March first, 1511, was to get rid both of Enciso and the leaders of the mob. He did this by sending the lawyer back to Spain, and then advising the others to follow and see that he did them no harm at court. He knew perfectly well that Enciso would complain to the King, and that the only excuses acceptable would be plenty of gold. As long as they sent him his royal share of that, his majesty cared but little what his loyal subjects did to each other in the far-off Indies. So Balboa looked for gold.

Luck favored him. As the rear-guard of Nicuesa's men were being brought from Nombre de Dios to Antigua they were met by two men, naked and painted like Indians, who addressed them in Spanish. They were sailors who had run away from one of Nicuesa's ships, a year and a half before, and had been kindly received by Careta, an Indian chief. One of them, Juan Alonso, had been made Careta's chief captain, and he basely offered to deliver to them with his own hands Careta, bound, and to betray his master's town to the Spaniards.

Balboa accepted the traitor's offer, marched to the town, and was hospitably received by Careta. After a pretended departure, he returned, rushed the town at night, devastated it, and carried off Careta and his family to Antigua. This was the ordinary way for Christians to repay Indian hospitality, both then and for a very long time afterwards. But what follows shows that Balboa was both kinder and shrewder than the average Spanish conqueror, who would undoubtedly have put Careta to death, now that he had seized his gold. Balboa, on the contrary, made peace with the chief and married his daughter. They agreed that Careta's people should supply Antigua with food, and the Spaniards help them against their enemies.

So, by matching tribe against tribe, Balboa conquered a great part of Darien. Comogre, the richest chief of all, received him peacefully, with a great present of gold. The Spaniards were weighing this out and squabbling over the division, when the chief's eldest son contemptuously threw the scales to the ground. If they cared for that sort of stuff, he exclaimed, they would find plenty of it to the south. There by a great sea on which they sailed in ships almost as large as those of the Spaniards were a people, who ate and drank out of vessels of gold. Thus the Spaniards heard for the first time of the Pacific and Peru.

Comogre's son offered to guide the white men to this sea and to let them hang him if they did not find it. But Balboa had heard of a wonderful golden temple of Dabaiba, somewhere up the Atrato River, and went up there to find it. He got no further than a country where the Indians lived in the tops of big trees, and dropped things on visitors. Having conquered this tribe, by cutting down the trees, and suppressed an attempted revolt

ENTRANCE TO OLD SPANISH PORT AT PORTO BELLO.

of five chiefs, Balboa loaded a ship with all the gold he could get, and sent it to Spain, to win him favor with the King. Then, as he knew that Enciso and his other enemies at court would be very busy, he decided to overwhelm them with the great news of his discovery of a new ocean.

So on the sixth of September, 1513, he set out to cross the Isthmus. Comogre's son had warned him that a thousand men would be needed to fight their way through, but Balboa had faith in his hundred and ninety well-armed Spaniards. They had with them bloodhounds, even more dreaded than themselves by the Indians, a train of native porters, and guides that led them by the best and shortest way. After some easy fighting and hard marching, they reached a hill, from the top of which, the Indians said, "the other ocean" could be seen. Halting his men, Balboa ascended alone, and was the first European to see the Pacific. This was September twenty-third, and it was six days later, on St. Michael's Day, when they reached the nearest part of the Pacific, which is still called, for that reason, the Gulf of San Miguel.

Wading into the great unknown ocean, Balboa took eternal possession, in the name of the King of Spain, of all its waters, and every shore they touched. To-day, Spain does not own an inch of land on that ocean. No one can point out the hill from which Balboa first saw the Pacific, and the Isthmus of Darien is less known to white men than it was four hundred years ago.

After a few of the local chiefs had been beaten in battle, and one, a wicked tyrant named Pacra, had been torn to pieces by the Spanish dogs, the others hastened to make friends with Balboa. They brought him a great deal of gold, besides pearls from the islands in the Gulf of San Miguel, and promised to collect much more. Suffering slightly from a fever, but without having lost

BALBOA.

one of his men, Balboa returned in triumph to Antigua, after an absence of a little less than four months. But it would have been far better for him if his great exploit had been accomplished only a few weeks sooner, so that his messenger could have reached Spain before the new governor had sailed for Darien. For this new governor who was to succeed Balboa, was the man who is seldom spoken of by his full name, Don Pedro Arias de Avila, but usually by his fearful nickname of "Pedrarias the Cruel."

CHAPTER V

HOW PEDRARIAS THE CRUEL BUILT OLD PANAMA

ENCISO'S complaints had decided the king to appoint a new governor, who should call Balboa to account. As usual, he picked a court favorite, Pedro Arias de Avila, called for short, Pedrarias Davila. He had served bravely as a colonel of infantry, and as he was now seventy years old, the king thought he could be counted on to attend strictly to the royal business, without having time to become dangerously powerful. But Pedrarias lived long enough to do more evil than any other man who ever came to the New World, before or since.

The news of Balboa's first successes brought in recruits, who were particularly attracted by the tale of a river so full of gold that the Indians strained it out with nets. Fully fifteen hundred crowded into the ships, instead of the twelve hundred sought for. Light wooden shields and quilted cotton jackets took the place of the steel armor that must have killed more men with sunstroke than it saved from the Indians' arrows. A Spanish historian of the time calls this expedition "the best equipped company that ever left Spain."

When the fleet reached Darien, the silk-clad messengers, sent on shore to seek Balboa, found him sitting in his underclothes and slippers, overseeing some Indians who were thatching a house. Even greater was the contrast when the new governor entered the town next day, with his wife, Dona Isabel, on one hand, and on the other a bishop in robes and miter, with friars chanting the Te Deum, and a train of gaily dressed cavaliers smiling scornfully at the tattered, sunburned colonists.

But not many weeks later, one of these same men in lace and satin staggered through the streets of Antigua, begging in vain for a morsel of food, and finally dropped dead in the sight of all. There was not enough food for such a multitude, and besides, the newcomers died by hundreds of the fevers. This is probably why Pedrarias did not at once put Balboa to death, under the pretext of what he had done to Nicuesa and Enciso. For although he was bitterly jealous of Balboa's success, Pedrarias realized that the other's men were seasoned veterans, and his own were sickly recruits. Besides, the bishop and some of the other officials befriended Balboa. So he was merely fined, imprisoned a few days, and then released. If he had been a wiser man, Balboa would have returned to Spain, where he was now a great hero, but instead, he stayed to watch Pedrarias at his work.

And dreadful work it was. Balboa had killed like a soldier, but Pedrarias tortured like a fiend. He had been instructed to establish a line of posts between the two oceans, and sent his lieutenant, Juan de Ayora, to locate the first fort at a place on the Atlantic coast called Santa Cruz. A chief who spread a feast for him, thinking to welcome his old friend Balboa, was tortured until he gave up all his gold, and then burned alive because it was not enough. As for the other chiefs Ayora caught, "some he roasted alive, some were thrown living to the dogs, some were hanged, and for others were devised new forms of torture." After several months of this, Ayora sneaked back to Antigua, stole a ship, and sailed away with all the gold so infernally won.

Another force crossed to the Pacific side and ravaged there, but were glad to fight their way back again, as all the tribes were rising. They were met by Indians waving the bloody shirts of the garrison of Santa Cruz. The blockhouse there had been stormed, and molten gold poured down the Spaniards' throats, while the Indians cried, "Eat the gold, Christians! Take your fill of gold!"

A hundred and eighty Spaniards, with three field-pieces, wandered into poisoned-arrow country, fell into an ambush, and were shot down to a man. An expedition

PIECES OF EIGHT.

was sent up the Atrato to find the Golden Temple of Dabaiba, but here too the Indians had the advantage. Being naked and good swimmers, they easily dived under and upset the canoes. Half the Spaniards were drowned, and Balboa, who was second in command, brought the rest back to Antigua. And though many other expeditions were later sent up the Atrato, none has ever reached Dabaiba, so the golden temple must be there to-day—if it ever was there at all.

Pedrarias, filled with fury at these defeats, took the field himself, but soon came down with a fever. Finally his alcalde, Espinosa, hurled himself with a sufficiently large force on the exhausted tribes and, by the beginning of 1517, established a Roman peace.

In the meanwhile, Balboa had been sent a royal commission as Adelantado of the South Seas, and Viceroy of the Pacific side of the Isthmus, but the jealous Pedrarias had held it up. Now Fonseca, the bishop, patched up a truce between the two. Balboa agreed to put away his Indian wife, and became engaged to the daughter of Pedrarias.

There was a place on the Atlantic shore, between Antigua and abandoned Santa Cruz, called by the Indians Acla, or "the Bones of Men," because two warlike chiefs of long ago had caused a great slaughter of their subjects there. Here Balboa cut down and shaped the timbers of four brigantines. These were carried by hundreds of Indians and a few negroes, over a rough trail to the headwaters of the Savannah River, down which they were rafted to the Gulf of San Miguel. It was an incredible piece of labor for the time, and none could have accomplished it but Nuñez de Balboa. When they came to set up the vessels, half the wood was found to be worm-eaten, and high tides and floods swept away much of the rest. But he persevered, until at last four fully equipped brigantines floated at anchor on the South Sea.

Then came word of a new governor sent from Spain to take the place of Pedrarias. Balboa confided to a friend that it might be wise for him to sail at once for Peru, "if this newcomer meant aught of ill to his lord Pedrarias." Now this false friend had been his rival for the love of the Indian girl, and revenged himself by denouncing Balboa to Pedrarias as a traitor. Francisco Pizarro was at once sent to arrest him, and, after a mockery of a trial, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, Adelantado of the South Sea, and noblest of the conquistadores, died on the scaffold in the plaza of Acla.

Fearing the wrath of the new governor, Pedrarias crossed the Isthmus, and in 1519, founded a city on the site of a little fishing village called Panama. This name signifies, in the Indian language, "a place abounding in fish," and one reason the Spaniards settled here was to escape the famines they had suffered at Antigua. Both that town and Acla were soon abandoned to the Indians, who even now forbid white men to stay overnight in that region under penalty of death, so well do they still remember the cruelties of Pedrarias.

I wish I could add that vengeance overtook that wicked old man, but he lived to rule and do evil, both in Panama and in Nicaragua, until he was ninety years old. The new governor died suddenly, and several in authority that came after him, including one bishop of Panama, were poisoned by Pedrarias. As for the Indians he caused to be killed, the historian Oviedo declares them to have been more than two million.

The only consolation we have is the knowledge that Pedrarias, who was even fonder of gold than of bloodshed, was at first a partner of Pizarro's, when the man who had arrested Balboa sailed on his ships to the conquest of Peru; but later, Pedrarias lost his courage, and sold his quarter-share in the adventure for a miserable thousand crowns. How it must have wrung the cruel old miser's heart to see the ship loads of silver and gold that came up from the mines of Peru, to be carried across the Isthmus on the way to Spain. For it was this treasure-trade with Peru that made the wealth and glory of Old Panama.

CHAPTER VI

HOW SIR FRANCIS DRAKE RAIDED THE ISTHMUS

SIXTY years after Balboa's discovery of the Pacific, the first Englishman to see that ocean looked at it from the top of a "goodlie and great high tree," somewhere in the jungle back of Old Panama. This man was Francis Drake, a bold sea-captain of Devon, who had come to the Isthmus to pay a debt he had long owed the Spaniards: a debt of revenge for treacherous wrong.

Five years before, in 1568, an English fleet under Sir John Hawkins had entered the harbor of San Juan de Ulloa (now Vera Cruz), in Mexico, ready either to trade peacefully with the Spaniards, or, if the latter preferred, to fight. The Spaniards received them as friends, exchanged hostages as evidence of good faith, waited until a very much larger Spanish fleet had come in, and then suddenly attacked the English with both ships and forts. After an all-day's fight, every English ship but two was captured, sunk, or ablaze; but the Minion of Hawkins, and Francis Drake's Judith fought their way out and carried the news to England. Queen Elizabeth could not go to war with Spain, then the mightiest power on earth, but she winked her royal eye at the private acts of her seamen.

Drake first made two quiet voyages to the Isthmus, to learn how the Spaniards handled the treasure-trade from Peru, and how he could best attack it. It is said that Drake even lived for a while in disguise at Nombre de Dios, which had been resettled and made the Atlantic port in 1519, the same year as the founding of Old Panama. A roughly paved way, called the Royal Road, had been built between the two cities by the forced labor of captive Indians, and over this in the dry season long trains of pack-mules carried the gold and silver that was brought up by sea from Peru to Panama, across the Isthmus to Nombre de Dios. During the nine months of the rainy season the route was over a better road from Panama to the little town of Venta Cruz, now called Cruces, at the head of navigation on the Chagres River, and down this river in flat-boats and canoes to the sea. Once a year a fleet of galleons came from Spain, bringing European goods for the colonists and carrying away the treasure that had been accumulating since the last trip in the King's treasure-house at Nombre de Dios. The English called this the "Plate Fleet," from the Spanish word plata, or silver.

Nombre de Dios was a ragged little town mostly bamboo huts and board shacks, except for the King's treasure-house, which was "very strongly built of lime and stone." The place was so unhealthy that it was known as "The Grave of the Spaniard," and most of the citizens spent the rainy season at Panama or Cruces, and only returned to Nombre de Dios to do business when the plate-fleet was in.

Drake learned all these things after two years' prowling up and down the coast, so in 1572 he made a third voyage to the Isthmus to put this knowledge to practical effect. Sailing boldly into Nombre de Dios harbor, at three o'clock in the morning on the twenty-ninth of July, Drake tumbled ashore with seventy-three men and captured

"NOMBRE DE DIOS"—STREET SCENE.

the sea-battery before the Spaniards could fire a single one of its six brass guns. Dismounting these, the English marched into the plaza, with drums beating, trumpets sounding, and six "fire-pikes" or torches lighting the way with a lurid glare. There was a volley of shot from the Spanish musketeers, an answering flight of English arrows, a rush, a brief, brisk hand-to-hand fight, and the defenders went flying through the landward gate and down the road to Panama.

In the governor's house the English found a stack of solid silver bars, seventy feet long, ten wide, and twelve high, worth more than five million dollars but too heavy to carry away. So they went to the King's treasure-house for the gold and jewels stored there. "I have brought you to the mouth of me treasury of the world!" cried Drake, and ordered them to break in the door. But an instant later, he fell fainting from loss of blood, for during the fight in the plaza he had received a great wound in the thigh, which he had kept concealed until then. And you can realize how much his men loved Francis Drake, when in spite of his commands they left the treasure to get their wounded captain back to the

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE.

Born in Devonshire, about 1540; died off Porto Bello, in 1596.

boats. The garrison and citizens were rallying, and more troops had just come from Panama, but all the English got safely off, except one of the trumpeters.

For the next six months Drake raided impudently up and down the coast, even capturing a ship in the harbor of Cartagena, the capital city of the Spanish Main,[5] and the Spaniards dared not attack him. Then, when his wound was healed, and the dry season had come, he set out with eighteen Englishmen and thirty Cimaroons from his secret camping-place on the Atlantic shore to cross the Isthmus. The Cimaroons were some of the many negroes who had been brought to the Isthmus as slaves, to take the place of the almost exterminated Indians, but had escaped from their Spanish masters into the jungle. Here they intermarried with the Indians, built towns of their own, and defied the Spaniards. Bands of Cimaroons, armed with bows and spears,—firearms were above their understanding—roamed the forest or raided pack-trains on the Royal Road. And this was what they were now helping Drake to do, as for centuries afterwards, both Cimaroons and Indians helped every enemy of Spain that came their way.

The galleons from Spain were at Nombre de Dios, waiting for the pack-trains to bring across the treasure from the other plate-fleet from Peru, that Drake saw riding at anchor in the harbor of Panama. He had not enough men to go near the city, but as soon as they had seen the Pacific from the "goodlie and great high tree" Drake and his comrade, John Oxenham, both took oath that they would some day sail an English ship on that sea.

A Cimaroon, sent into the city as a spy, brought out the news that three pack-trains were to leave Panama that night, traveling by moonlight to escape the heat, and laden, one with provisions, one with silver, and one with gold and jewels. A carefully planned ambush was laid on either side of the Royal Road, not far from Venta Cruz, but a silly sailor, named Robert Pike, spoiled everything by jumping up to look at a Spaniard who came riding out from the town. This horseman warned the train-escort, who sent forward the mules loaded with provisions. When Drake captured these, he knew the treasure-train had escaped him, so he charged into Venta Cruz to see what he could find there. But there was no treasure in the village, only some Spanish ladies who were dreadfully frightened, until Drake assured them that no woman or unarmed man had ever been harmed by him.

NATIVES PREPARING RICE FOR DINNER—NOMBRE DE DIOS.

When he had returned to the Atlantic side of the Isthmus, Drake joined forces with some English freebooters, and they laid another ambush on the Royal Road, this time only a mile out of Nombre de Dios. At dawn, a string of a hundred and ninety mules came tinkling and pattering along from Panama, with an escort of forty-five Spanish soldiers. A volley dropped the lead-mules, the rest promptly lay down, and the escort broke and ran to Nombre de Dios, leaving Drake's men the richer by fifteen tons of gold and as much silver. The latter they buried round about, in the holes of the land-crabs, and it is said that the Spaniards were never able to find it, and that it must be there to-day. As for the gold, Drake divided it fairly, and sailed back to England with his share.

Two years later, in 1575, John Oxenham returned to the Isthmus, crossed it with the aid of the Cimaroons, built and launched a pinnace on the southern side, and

SAN BLAS INDIAN SQUAWS IN NATIVE DRESS.

Note the gold nose-rings.

was the first Englishman to sail the Pacific. How he raided the Pearl Islands and was captured and put to death by the Spaniards from Panama, you can read best in Kingsley's noble story of "Westward Ho!"

It was left for Drake to enter this sea that Spain had claimed for her own, through the strait Magellan had found in 1520, and to be the next after him to sail round the world. How, with one little ship, the Golden Hind, Drake swept the west coast of South America, and took the great treasure-galleon Cacafuego a hundred and fifty leagues from Panama; how with a fleet he took and burned the city of Santo Domingo (but spared the cathedral because it held the ashes of Christopher Columbus), and sacked Cartagena; how with Sir John Hawkins he wiped out the memory of San Juan de Ulloa in the great Armada fight; how he won knighthood and "singed the King of Spain's beard," are all parts of another noble story for which there is no room here.