A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Schools of Composition

SCHOOLS OF COMPOSITION. In Music, as in other Arts, the power of invention, even when displayed in its most original form, has a never-failing tendency to run in certain recognised channels, the study of which enables the technical historian to separate its manifestations into more or less extensive groups, called Schools, the limits of which are as clearly defined as those of the well-known Schools of Painting, or of Sculpture. These Schools naturally arrange themselves in two distinct Classes; the first of which embraces the works of the Polyphonic Composers of the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries, written for Voices alone; the second, those of Composers of later date, written, either for Instruments alone, or for Voices supported by Instrumental Accompaniments. The critical year, 1600, separates the two classes so distinctly, that it may fairly be said to have witnessed the destruction of the one, and the birth of the other. It is true that some fifty years or more elapsed, before the traditions of the earlier style became entirely extinct; but their survival was rather the result of skilful nursing, than of healthful reproductive energy; while the newer method, when once fairly launched upon its career, kept the gradual development of its limitless resources steadily in view, with a persistency which has not only continued unabated to the present day, but may possibly lead to the accomplishment, in future ages, of results far greater than any that have been yet attained.

The number of distinct Schools into which these two grand Classes may be subdivided is very great—so much too great for detailed criticism, that we must content ourselves with a brief notice of those only which have exercised the most important influence upon Art in general. In making a selection of these, we have been guided, before all things, by the principles of æsthetic analogy, though neither local nor chronological coincidences have been overlooked, or could possibly have been overlooked, in the construction of the following scheme, in accordance with which we propose to arrange the order of our leading divisions.

I. The Art of Composition was long supposed to have owed its origin to the intense love of Music which prevailed in the Low Countries, during the latter half of the 14th century. The researches of modern criticism have proved this hypothesis to be groundless, so far as its leading proposition is concerned: yet, it contains so much collateral truth, that, while awaiting the results of farther investigation, we are still justified in representing Flanders as the country whence the cultivation of Polyphony was first disseminated to other lands. If the Netherlanders were not the arliest Composers, they were, at least, the first Musicians who taught the rest of Europe how to compose. And, with this certain fact before us, we have no hesitation in speaking of The First Flemish School as the earliest manifestation of creative genius which can be proved to have exercised a lasting influence upon the history of Art. The force of this assertion is in no wise invalidated by the strong probability that the Faux-bourdon was first sung in France, and exported thence, at a very early period, to Italy. For the primitive Faux-bourdon, though it indicated an immense advance in the practice of Harmony, was, technically considered, no more than a highly-refined development of the extempore Organum, or Discant, of the 11th and 12th centuries, and bore very little relation to the true 'Cantus super librum,' to which, alone, the term Composition can be logically applied. We owe, indeed, a deep debt of gratitude to the Organizers, and Discanters, by whom it was invented; for, without the materials accumulated by their ingenuity and patience, later Composers could have done nothing. They first discovered the harmonic combinations which have been claimed, as common property, by all succeeding Schools. The misfortune was that with the discovery their efforts ceased. Of symmetrical arrangement, based upon the lines of a preconceived design, they had no idea. Their highest aspirations extended no farther than the enrichment of a given Melody with such Harmonies as they were able to improvise at a moment's notice: whereas Composition, properly so called, depends, for its existence, upon the invention—or, at least, the selection—of a definite musical idea, which the genius of the Composer presents, now in one form, and now in another, until the exhaustive discussion of its various aspects produces a work of Art, as consistent, in its integrity, as the conduct of a Scholastic Thesis, or a Dramatic Poem. Upon this plan, the Flemish Composers formed their style. They delighted in selecting their themes from the popular Ditties of the period—little Volkslieder, familiar to men of all ranks, and dear to the hearts of all. These they developed, either into Sæcular Chansons for three or more Voices, or into Masses and Motets of the most solemn and exalted character; with no more thought of irreverence, in the latter case, than the Painter felt, when he depicted Our Lady, resting, during her Flight into Ægypt, amidst the familiar surroundings of a Flemish hostelry. At this period, representing the Infancy of Art, the Subject, or Canto fermo, was almost invariably placed in the Tenor, and sung in long-sustained notes, while two or more supplementary Voices accompanied it with an elaborate Counterpoint, written, like the Canto fermo itself, in one or other of the antient Ecclesiastical Modes, and consisting of Fugal Passages, Points of Imitation, or even Canons, all suggested by the primary idea, and all working together for a common end. This was Composition, in the fullest sense of the word; and, as the truth of the principle upon which it was based has never yet been disputed, the Musicians who so successfully practised it are entitled to our thanks for the cultivation of a mode of treatment the technical value of which is still universally acknowledged.

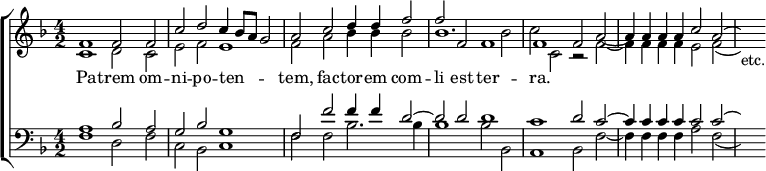

The reputed Founder of the School, and unquestionably its greatest Master, was Gulielmus Dufay, a native of Chimay, in Hennegau, who, after successfully practising his Art in his own country, and probably also at Avignon, carried it eventually to Rome, where, in 1380, he obtained an appointment in the Papal Choir, and where he appears to have died, at an advanced age, in 1432, leaving behind him a goodly number of disciples, well worthy of so talented a leader. The most eminent of these were, Egydius Bianchoys, Vincenz Faugues, Egyd Flannel (called L'Enfant), Jean Redois, Jean de Curte (called L'Ami), Jakob Ragot, Eloy, Brasart, and others, many of whom sang in the Papal Chapel, and did their best to encourage the practice of their Art in Italy. A valuable collection of the works of these early Masters is preserved among the Archives of the Sistine Chapel, but very few are to be found elsewhere,[1] with the exception of some interesting fragments printed by Kiesewetter, Ambros, Coussemaker, and some other writers on the History of Music. The following passage from Dufay's 'Missa l'omme armé'—one of the greatest treasures in the Sistine Collection—will serve to exemplify the remarks we have made upon the general style of the period.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

II. The system thus originated was still more fully developed in The Second Flemish School, under the bold leadership of Joannes Okenheim (or Ockeghem), of whom we first hear, as a member of the Cathedral Choir at Antwerp, in the year 1443. Okenheim's style, like that of his fellow-labourers, Antoine Busnoys,[2] Jakob Hobrecht, Philipp Basiron, Jean Cousin, Jacob Barbireau, Erasmus Lapicida, Antoine and Robert de Fevin, Firmin Caron, Joannes Regis, and others, of nearly equal celebrity, was more elaborate, by far, than that of either Dufay himself, or the most ambitious of his colleagues; and there is little doubt that the industry of these pioneers of Art assisted, materially, in preparing the way for the splendid creations of a later epoch. The ingenuity displayed by the leader of the School in the construction of Canons and imitations of every conceivable kind, led to the extensive adoption of his method of working by all who were sufficiently advanced to enter into rivalry with him; and, for many years, no other style was tolerated. He, however, maintained his supremacy to the last; and if, in his desire to astonish, he sometimes forgot the higher aims of Art, he at least bequeathed to his successors an amount of technical skill which enabled them to overcome with ease many difficulties, which, without such a leader, would have been insurmountable. The greater number of his Compositions still remain in MS., among the Archives of the Pontifical Chapel, in the Brussels Library, and in other collections; but some curious examples are preserved in Petrucci's 'Odhecaton,' and 'Canti C. No. cento cinquanta,' and in the 'Dodecachordon' of Glareanus; while others, in modern notation, will be found in Burney, vol. ii. pp. 474–479, in vol. i. of Rochlitz's 'Sammlung vorzüglichen Gesangstücke,' and in the Appendix now in course of publication, by Otto Kade, in continuation of Ambros's 'Geschichte der Musik.'

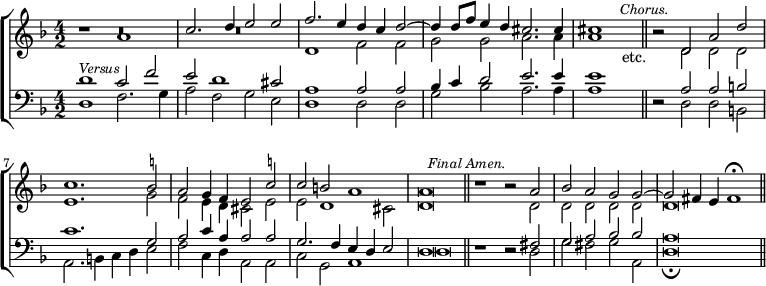

III. To Okenheim was granted the rare privilege, not only of bringing his own School to perfection, but also of educating the orginator of another, which was destined to exercise a still stronger influence upon the future of Polyphony. In his famous disciple, Josquin des Prés, he left behind him a successor, no less learned and ingenious than himself, and infinitely richer in all those great and incommunicable gifts which form the distinguishing characteristics of true genius. All that one man could teach another, he taught the quondam Chorister of S. Quentin; but a comparison of the works of the two Composers will clearly show, that the technical perfection beyond which the teacher never dreamed of penetrating was altogether insufficient to satisfy the aspirations of the pupil, in whose Music we first find traces of a desire to please the ear, as well as the understanding. It is the presence of this desire, joined with improved symmetry of form, and increased freedom of development, which distinguishes The Third Flemish School, of which Josquin was the life and soul, from its ruder predecessors. This was the first School in which any serious attempt was made to use learning as a means of producing harmonious effect; and it was rich in Masters, who, however great their inferiority to their unapproachable leader, caught not a little of his fire. Pierre de la Rue (Petrus Platensis), Antonius Brumel, Alexander Agricola, Loyset Compère, Johann Ghiselin, Du Jardin (Ital. De Orto), Matthaus Pipelare, Nicolaus Craen, and Johann Japart, though the greatest, were by no means the only great writers of the age; and the list of less celebrated names is interminable. The works of these Masters, though not easily accessible to the general reader, are well represented in the 'Dodecachordon.' Petrucci, too, has printed three entire volumes of Josquin's Masses, besides many others by contemporary writers; and the same publisher's 'Odhecaton,' and 'Canti B. and C.' contain a splendid collection of sæcular Chansons by all the best Composers of the period. The most important example, in modern Notation, is Choron's reprint of Josquin's 'Stabat Mater,' the general style of which is well shown in the following brief extract.[3]

Modus XIII (vel XI) Transp.[4]

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

IV. The style of The Fourth Flemish School presents a strong contrast to that of its predecessor. The earlier decads of the 16th century did, indeed, produce many writers, who slavishly imitated the ingenuity of Josquin, in utter ignorance of the real secret of his strength; but the best Masters of the time, finding it impossible to compete with him upon his own ground, struck out an entirely new manner, the chief characteristic of which was, extreme simplicity of intention, combined with a greater purity of Harmony than had yet been attempted, and a freedom of melody which lent a fresh charm, both to the Ecclesiastical and the Sæcular Music of the period. The greatest Masters of this School were, Nicolaus Gombert, Cornelius Canis, Philippus de Monte, Jacobus de Kerle, Clemens non Papa; the great Madrigal writers, Philipp Verdelot, Giaches de Wert, Huberto Waelrant, and Jacques Archadelt; Adrian Willaert, the Flemish Founder of the Venetian School; and the last great genius of the Netherlands, Roland de Lattre (Orlando di Lasso), of whose work we shall have occasion to speak at a later period. To these industrious Netherlanders the outer world was even more deeply indebted than to those of the preceding century, for its knowledge of the Art, which, so well nurtured in the Low Countries, spread thence to every Capital in Europe; and it is chiefly by the peculiar richness of their otherwise unpretending Harmonies that their works are distinguished from those of earlier date—a characteristic which is well illustrated in the following example, from Philippus de Monte's 'Missa, Mon cueur se recommande a vous,' and to which we call special attention, as we shall frequently have occasion to refer to it, hereafter, in tracing the relationship between cognate schools.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

That the style we have described was the result of a reaction, neither unhealthy in its nature, nor revolutionary in its tendency, though not altogether free from violence, there can be no doubt. Singers were growing weary of the conundrums which had so long been offered to them as substitutes for the truer Music which alone can reach the heart. In the hands of Josquin, these puzzles had never lacked the impress of true genius. In those of his imitators, they were as dry as dust. With him, the solution of the ænigma led always to some harmonious result; while they were perfectly satisfied, provided no rules were unnecessarily broken. The best men of the period, fully alive to the importance of this distinction, aimed at the harmonious effect, and succeeded in attaining it, without the intervention of the conundrum. And thus arose a School, so simple in its construction, that more than one modern critic has accused its leaders of poverty of invention. The injustice of this charge is palpable; for when it answered the purpose of these Composers to write in a more learned manner, they invariably found themselves equal to the occasion, though they cared nothing for ingenuity for its own sake. And the result of their spirit of self-control is, that though their Church Music may be deficient in the breadth and grandeur which were attained, at a later period, in Italy, their Madrigals are among the finest in the world.

Beyond this point, Art made no great advance in Flanders. We must seek for the traces of its farther progress in Italy. [See Polyphonia; Mass; Madrigal; Josquin; Obrecht; Okeghem; etc. etc.]

V. The formation of The Early Roman School was one of the most important, as well as the most obviously natural results of the employment of Flemish Musicians in the Pontifical Chapel. It was not, however, until many years after the return of the Papal Court from Avignon, that Italian Composers were able to hold their ground successfully against their foreign rivals. When they did begin to do so, the style they most affected was so strongly influenced by that then prevalent in the Netherlands, that it is not always easy to distinguish works of the one School from those of the other, as a comparison of the following passage from Costanzo Festa's Madrigal, 'Quando ritrovo la mia pastorella,'[5] with the opening of Archadelt's 'Vaghi pensier,'[6] will sufficiently demonstrate.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Va -- ghi pen -- sier che co -- si pas -- so pas -- so, che co -- si pas -- so pas -- sp Scor -- to m'ha -- ve -- te ra -- gio -- nar'

In the distribution of their Vocal Parts, the massive weight of their Harmonies, the persistent crossing of the Melodies by which those Harmonies are produced, the bright swing of their Rhythm, and other similar technicalities, these two examples resemble each other so closely, that, had they been printed anonymously, no one would ever have supposed that they could possibly have belonged to different Schools. The secret is explained by their simultaneous publication in Venice. The Netherlanders had long found a ready market for their Art Treasures, in Italy. The Italians had, by this time, learned how to produce similar treasures for themselves; and Costanzo Festa's talent placed his works at least on a level with those of his instructors, if not above them. His genius was incontestable: he was equally remarkable for his power of adaptation. Though by no means wanting, either in learning, or ingenuity, he here shows himself willing to reduce his Madrigal to the simplicity of a Faux-bourdon, in order to secure the harmonic richness so highly prized at this particular epoch. He did so, constantly, and always with success; for, to the purity of style cultivated by the best of his contemporaries in the North of Europe, Festa added a Southern grace, which has gained him a high place among the Masters of early Italian Art. He had, indeed, but few rivals among his own countrymen. With the exception of Giovanni Animuccia, and some few Italian writers of lesser note, nearly all the best Composers for the great Roman Choirs, at this period, were Spaniards. Among these, we find the names of Bartolommeo Escobedo, Francesco Salinas, Juan Scribano, Cristofano Morales, Francesco Guerrero, Didaco Ortiz, and Francesco Soto all Masters of the highest rank, of whom, notwithstanding their close imitation of Flemish models, we shall have occasion to speak again, when treating of the Spanish School; though none of them were so worthy as Festa himself to sustain the honour of this most interesting phase of artistic development—the first in which his country asserted her claim to special notice.

VI. Italy was once represented, by general consent, as the birthplace of all the Arts. We have shown, that, with regard to Polyphony, this was certainly not the case. We are now, however, approaching a period in which she undoubtedly took the lead, and kept it. The middle of the 16th century witnessed a rapid advance towards perfection, in many centres of technical activity; but the triumphs of this, and all preceding epochs, were destined, ere long, to be entirely forgotten in those of The Later Roman School.

We have seen Polyphonic Art nurtured, in its infancy, by the protecting care of Dufay; in its childhood, by that of Okenheim; in the bright years of its promising adolescence, by the stronger support of Josquin, and of Festa. We are now to study it, in its full maturity, enriched by the genius of one, compared with whom all these were but as experimenters, groping in the dark. The train of events which led to the recognition of the School justly held to represent 'The Golden Age of Art' has already been discussed, at some length, [7]elsewhere; but it is necessary that we should refer to it again, in order to render the sequence of our narrative intelligible to the general reader. We have shown that the process of technical development which was gradually bringing the Motet and the Madrigal to absolute perfection of outward form, had never been interrupted. Unhappily, the spirit which should have prompted the Composer of the 16th century to draw the necessary line of demarcation between Ecclesiastical and Sæcular Music, and to render the former as worthy as possible of the purpose for which it was intended, attracted far less attention than the advantage to be derived from structural improvement. Among the successors of Josquin, there were many cold imitators of his mechanism, who, as we have already shown, were totally unable to comprehend the true greatness of his style. By these soulless pedants—more numerous, by far, than their more earnest contemporaries—the Music of the Mass was degraded into a mere learned conundrum; enlivened, constantly, by the introduction, not only of sæcular subjects, but of profane words also. Other practices, equally vicious and equally irreverent, were gradually bringing even the primary intention of Religious Art into disrepute. For, surely, if Church Music be not so conceived as to assist in producing devotional feeling, it must be something very much worse than worthless: and, to suppose that any feeling, other than that of hopeless bewilderment, could possibly be produced by a Mass, or Motet, exhibiting a laboured Canon, worked out, upon a long-drawn Canto fermo, by four or more Voices, all singing different sets of words entirely unconnected with each other, would be simply absurd. The Council of Trent, dreading the scandal which such a style of Music must necessarily introduce into the public Services of the Church, decided that it would be desirable to interdict the use of Polyphony altogether, rather than suffer the abuse to continue. And the prohibition would actually have been carried into effect, had not Palestrina saved the Art he practised, by showing, in the 'Missa Papæ Marcelli,' how learning as profound as that of Okenheim or Josquin, might be combined with a greater amount of devotional feeling than had ever before been expressed by a Choir of human Voices. It was this great Mass which inaugurated the later Roman School; and the year 1565, in which it was produced, has always been regarded as marking a most important crisis in the history of Art, a crisis which it behoves us to consider very carefully, since its nature has generally been discussed, either so superficially as to give the enquiring student no idea whatever of its distinctive character, or with blind adherence to a foregone conclusion equally fatal to the just appreciation of its import.

A century ago, the genius of Palestrina was very imperfectly understood. The spirit of the cinquecentisti no longer animated even the best Composers for the Church; and modern criticism had not, as yet, made any attempt to bring itself en rapport with it. Hawkins, less trustworthy as a critic than as an historian, tells us, that the great Composer 'formed a style, so simple, so pathetic, and withal so truly sublime, that his Compositions for the Church are even at this day looked upon as the models of harmonical perfection.' It is quite true that his style is 'truly sublime,' and, where deep feeling is needed, unutterably 'pathetic': but, though it may appear 'simple' to the uninitiated, it is really so learned and ingenious that it needs a highly accomplished contrapuntist to unravel its complications. Burney, though generally no less remarkable for the fairness of his criticism, than for the indefatigable perseverance with which he collected the evidence whereon it rests, tells us, in like manner, that the 'Missa Papæ Marcelli' is 'the most simple of all Palestrina's works': yet, a glance at the Score will suffice to show that much of it is written in Real Fugue, and close Imitation, of so complex a texture as to approach the character of Canon.[8] Not very long ago, this wonderful Mass was supposed to possess certain constructive peculiarities which not only marked it out as the greatest piece of Church Music that ever was conceived—as it undoubtedly is—but which also interposed, between Music written before, and that produced after it, a gulf as unfathomable as that which separates the Polyphony of the 16th century from the Monodia of the 17th. No idea can possibly be more fallacious. The true Ecclesiastical Style, as determined by the 'Missa Papæ Marcelli,' differs from that which preceded it, not in its technical, but in its æsthetic character. In so far as its external mechanism is concerned, it exhibits no contrivances which were not already well known to Okenheim, Josquin des Prés, Goudimel, and a hundred other writers of inferior reputation. It was not for the sake of its faultless symmetry, that it was selected as the model of Ecclesiastical purity. Ambros, indeed, denies that it ever served as a model at all; that it effected any reform whatever in the style of Ecclesiastical Music; or even that any such reform was needed, at the time of its production. This position, however, is untenable. The opinion of a critic so learned, so talented, and, generally, so unprejudiced as Ambros, must not be lightly contravened: but, it is certain that the Council of Trent did not exaggerate the necessity for a reform, immediate, stern, and uncompromising; and, equally so, that that reform was effected by means of this Mass alone. What, then, was the secret of this wondrous revolution? It lay in the subjugation of Art to the service of Nature, of learning to effect, of ingenuity to the laws of beauty. Palestrina was the first great genius who so concealed his learning as to cause it to be absolutely overlooked in the beauty of the resulting effect. If it was given to Okenheim to unite the dry bones of Counterpoint into a wondrously articulated skeleton, and to Josquin to clothe that skeleton with flesh; to Palestrina was committed the infinitely higher privilege of endowing the perfect form with the spirit which enabled it, not only to live, but to give thanks to God in strains such as Polyphony had never before imagined. It was not the beauty of its construction, but the presence of the soul within it, that rendered his Music immortal. He was as much a master of contrivance as the most accomplished of his predecessors; but while they loved their clever devices for their own sake, he only cared for them in so far as they served as means for the attainment of something better. And, though his one great object in introducing this new feature as the basis of his School was the regeneration of Church Music, it was impossible that his work should rest there. In establishing the principle that Art could only be rightly used as the handmaid of Nature, he not only provided that the Mass and the Motet should be devotional; but, also, that the Chanson and the Madrigal should be sad, or playful, in accordance with the sentiment of the verses to which they were adapted. His reform, therefore, though first exemplified in the most perfect of Masses, extended afterwards to every branch of Art. The Canzonetta felt it as deeply as the Offertorium; the Frottola, as certainly as the Faux-bourdon. Henceforth, Imitation and Canon, and the endless devices of which they form the groundwork, were estimated at their true value. They were cultivated as precious means, for the attainment of a still more precious end. And, the new life thus infused into the Art of Counterpoint, in Italy, extended, in a wonderfully short space of time, to every contemporary centre of development in Europe; though the great Roman School monopolised, to the last, the one strong characteristic which, more than any other, separates it from all the rest—the absolute perfection of that ars artem celandi which is justly regarded as the most difficult of all arts. In this, Palestrina excelled, not only all his predecessors and contemporaries, without exception, but all the Polyphonic Composers who have ever lived. Nor has he ever been rivalled in the perfect equality of his Polyphony. Whatever may be the number of Parts in which he writes, none ever claims precedence of another. Neither is any Voice ever permitted to introduce itself without having something important to say. There is no such thing as a 'filling up of the Harmony' to be found in any one of his Compositions. The Harmony is produced by the interweaving of the separate Subjects; and when, astonished by the unexpected effect of some strangely beautiful Chord, we stop to examine its structure, we invariably find it to be no more than the natural Consequence of some little Point of Imitation, or the working out of some melodious Response, which fell into the delicious combination of its own accord. In no other Master is this peculiarity so strikingly noticeable. It is no uncommon thing for a great Composer to delight us with a lovely point of repose. The later Flemish Composers do this continually. But they always put the Chord into its place, on purpose; whereas Palestrina's loveliest Harmonies come of themselves, while he is quietly fitting his Subjects together, without, so far as the most careful criticism can ascertain, a thought beyond the melodic involutions of his vocal phrases. How far the Harmonies form a preconceived element in those involutions is a question too deep for consideration here.

The features to which we have drawn attention, as most strongly characteristic of Palestrina's peculiar style, were imitated, without reserve, by the greatest Composers of his School; and though, in no case, does the Scholar ever approach the perfection reached by the Master, we find the same high qualities pervading the works of Vittoria, Giovanni Maria and Bernadino Nanini, Felice and Francesco Anerio, Luca Marenzio, and all the best writers of the period. The School continued, in full prosperity, until the closing years of the 16th century; and its traditions were gratefully followed, even late into the 17th, by a few loyal disciples, whose line closed with Gregorio Allegri, in 1652. These, however, were but the last devoted lovers of an Art which ceased to live within a very few years after the death of the gifted writer who brought it to perfection. With the age of Palestrina, the reign of true Polyphony came to an end. But it took firm root, and bore abundant fruit, during his lifetime, in many distant countries; and the Schools in which it was most successfully cultivated were those which most carefully carried out the principle of his great reform.

VII. The Flemish descent of The Venetian School is even more clearly traceable than that of its Roman sister; notwithstanding the well-known fact that Italian Musicians were employed in the service of the Republic, long before the time of Dufay. For, though the Archives of S. Mark's prove the existence of a long line of Organists, stretching back as far as the year 1318, when the office was held by a Venetian, described as Mistro Zuchetto,[9] we meet with no sign of the formation of a School, before the third decad of the 16th century, by which time the Art of the Low Countries had made its mark in every city in Europe. This circumstance, however, reflects no discredit upon the earlier virtuosi, whose extempore performances upon the Organ, though famous enough in their day, left, of course, no permanent record behind them. Even the first Maestro di Cappella, Pietro de Fossis—a Netherlander, of high reputation, who was presented with the appointment, together with that of Master of the Choristers, in 1491—seems to have been less celebrated as a Composer, than as a Singer. At any rate, since no trace of his productions can now be discovered, either printed or in MS., the title of the Founder of the School justly devolves upon his successor, Adriano Willaert, than whom a stronger leader could scarcely have been found. Born, at Bruges, in 1480[10] and received as a pupil, first, by Okenheim, and afterwards, in Paris, by Josquin des Prés—or, as some imagine, by Mouton—this great representative of Flemish genius succeeded De Fossis, as Maestro di Cappella, in 1527, and, during thirty-five years of unwearied industry, enriched the Library of S.Mark's with a magnificent repertoire of Masses, Motets, Psalms, Canticles, and other Ecclesiastical Music, besides delighting the world with innumerable Madrigals, Canzonets, and other sæcular pieces, among which his 'Villanellæ Neapolitanæ,' à 4, stand almost unequalled for prettiness and freedom. His style presents all the best characteristics of the Later Flemish School, tempered by a rich warmth which was doubtless induced by his long residence in the most romantic city in the world. Unfortunately, though many volumes of his works were published during his lifetime, but few have been reproduced in modern Notation. A Motet, à 4, will, however, be found at p. 474, vol. ii. of Hawkins's History. [See Willaert.]

Willaert's successors in office were, Cipriano di Rore, who held the appointment from 1563 to 1565; Zarlino, (1565–1590); Baldassare Donati, (1590–1603), and the last great Master of the School, Giovanni dalla Croce, who was unanimously elected in 1603, and died, after five years service, in 1609. These accomplished Musicians, together with Andrea Gabrieli, who played the second Organ from 1566 to 1586, and his nephew, Giovanni, who presided over the first from 1585 to 1612, proved themselves faithful disciples of their venerable leader, cultivating, to the last, a style which combined the rich Harmony of the Netherlands with not a little of the melodic independence which we have described as peculiarly characteristic of the best Roman period. Upon this was engrafted, in the finest examples, a certain tenderness of manner, in which Croce, especially, has scarcely ever been surpassed. Still, it is always evident that the harmonious effect is the result of the Composer's primary intention, and not, as in the greatest works of the Roman School, of the interweaving of still more important melodic elements; a feature which is well illustrated by comparing the extract from the 'Missa Papæ Marcelli,' given at vol. ii. page 230, with the following fragment from Andrea Gabrieli's 'Missa Brevis.'

VIII. THE EARLY FLORENTINE SCHOOL, though far less important than that of Venice, is not destitute of special interest. A gorgeous MS., once the property of Giuliano de' Medici, and still in excellent preservation, contains Compositions by no less than seven Florentine Musicians of the 14th century. Many works of antient date are also extant, in the collections of Petrucci, and other early printers. The beauties of these are, however, entirely forgotten, in those of the more celebrated School, founded by Francesco Corteccia, who, in the earlier half of the 16th century wrote some excellent Church Music, and a number of beautiful Madrigals, the style of which differs, very materially, from that cultivated in other parts of Italy, assimilating, indeed, far less closely to the character of the true Madrigal, than to that of the Frottola—a lighter kind of composition, more nearly allied to the Villanella, or Fa la. On the occasion of the marriage of Cosmo I. de' Medici with Leonora of Toledo, in 1539, Corteccia, in conjunction with Matteo Rampollini, Pietro Masaconi, Baccio Moschini, and the Roman Composer, Costanzo Festa, wrote the Music for an entertainment consisting almost entirely of Madrigals, intermixed with a few Instrumental pieces, the whole of which were printed at Venice, by Antonio Gardane. A similar performance graced the marriage of Francesco de' Medici with Bianca Capello, in 1579, on which occasion Palestrina contributed his Madrigal 'O felice ore.' For such festivities as these, the Florentines were always ready; but their greatest triumph was reserved for a later period, which must be discussed in the second division of our subject.

IX. The Schools of Lombardy were always very closely allied to those of Venice: indeed, the geographical relations of the two Provinces favoured an interchange of Masters which could scarcely fail to produce a close similarity, if not identity of style. Costanzo Porta, the greatest of Lombard Masters, though a native of Cremona, spent the most productive portion of his life at Padua. Orazio Vecchi wrote most of his best works at Modena. Apart from these, the best writers of the School were Ludovico Balbo (Porta's greatest pupil), Giac. Ant. Piccioli, Giuseppe Caimo, Giuseppe Biffi, Paolo Cima, Pietro Pontio, and, lastly, Giangiacomo Gastoldi, who brought the Fa la, the Frottola, and the Balletto, to a degree of perfection which has rarely, if ever, been equalled. The Lombard School also claims as its own the famous Theorist, Franchinus Gafurius, who wrote most of his more important works at Milan, though the earliest known edition of his earliest production appeared at Naples, in 1480.

X. To The Neapolitan School belongs another Theorist of distinction, Joannes Tinctoris, the compiler of the first Musical Dictionary on record.[11] Naples also claims a high place, among her best Composers, for Fabricio Dentice, who lived so long in Rome, that he is usually classed among the Roman Masters, though he was undoubtedly, by birth, a Neapolitan, and a bright ornament of the School; as were also Giov. Leon, Primavera, Luggasco Luggaschi, and other accomplished Madrigalists, whose lighter works take rank with the best Balletti and Frottole of Milan and Florence.

XI. The School of Bologna exhibits so few characteristics of special interest, that we may safely dismiss it, with those of other Italian cities of less importance, from our present enquiry, and proceed to study the progress of Polyphony in other countries.

XII. The Founder of The German Polyphonic School was Adam de Fulda, born about 1460; a learned Monk, more celebrated as a writer on subjects associated with Music, than as a Composer, though his Motet, 'Overa lux et gloria,' printed by Glareanus, shows that his knowledge of Counterpoint was not confined to its theoretical side. This remarkable Composition, like the more numerous works of Heinrich Finck (a contemporary writer, of great and varied talent), Thomas Stolzer, Hermann Finck (a nephew of Heinrich), Heinrich Isaak, Ludwig Senfl, and others long forgotten even by their own countrymen, bears so close an analogy to the style cultivated in the Netherlands, that it is impossible to imagine the German Masters obtaining their knowledge from any other source than that provided by their Flemish neighbours. Isaak—born about 1440—was one of the most learned Contrapuntists of the period, and, in all essential particulars, a follower of the Flemish School; though his talent as a Melodist was altogether exceptional. It seerns quite certain that he was the Composer of the grand old Tune, 'Inspruck, ich muss Dich lassen,' afterwards known as 'Nun ruhen alle Wälder,' and 'O Welt, ich muss Dich lassen,' and treated over and over again by Sebastian Bach, in his Cantatas.[12] And this circumstance introduces us to an entirely new and original feature in the German School. The progress of the Reformation undoubtedly retarded the development of the higher branches of Polyphony very seriously. With the discontinuance of the Mass, the demand for ingenuity of construction came to an end; or was, at best, confined to the Sæcular Chanson. But, at the same time, there arose a pressing necessity for that advanced form of the Faux-bourdon which so soon developed itself into the Four-part Choral; and, in this, the German Composers distinguished themselves, if not above all others, at least as the equals of the best contemporary writers—witness the long list of Choral books, from the time of Walther to the close of the 17th century. We all know to what splendid results this new phase of Art eventually led; but, for the time being, it acted only as a hindrance to healthful progress; and, notwithstanding the good work wrought by Nicholas Paminger, the last great Master of the School, who died at Passau in 1608, it would, in all probability, have produced a condition of absolute stagnation, but for an unforeseen infusion of new life from Italy.

XIII. The Schools of Munich and Nuremberg must be regarded, not as later developments of Teutonic Art, but as foreign importations, to which Germany was indebted for an impulse which afterwards proved of infinite service to her. They were founded, respectively, by Orlando di Lasso, and Hans Leo Hasler; the first a Netherlander, and the last a true German. Of Orlando di Lasso, so much has already been recorded, in our second volume, that it is unnecessary to dilate upon his history here. Suffice it then to say, that, thanks to his long residence in Italy, his style united all the best qualities of the Flemish and the Italian Schools, and enabled him to set an example, at Munich, which the Germans were neither too cold to appreciate, nor too proud to turn to their own advantage. Hasler was born, at Nuremberg, in 1564; but learned his Art in Venice, under Andrea Gabrieli, whose nephew, Giovanni, was his fellow pupil, and most intimate friend. So thoroughly did he imbibe the principles and manner of the School in which he studied, that the Venetians themselves considered him as one of their own fraternity, Italianising his name into Gianleone. His works possess all the rich Harmony for which Gabrieli himself is so justly famous, and all the Southern softness which the Venetian Composers so sedulously cultivated; and are, moreover, filled with evidences of consummate contrapuntal skill, as are also those of his countrymen, Jakob Handl (= Jacobus Gallus), Adam Gumpeltzheimer, Gregor Aichinger, and many others, who, catching the style from him, spread it abroad throughout the whole of Germany.[13] Of its immediate effect upon the native Schools, we can scarcely speak in more glowing terms than those used by the German historians themselves. Of its influence upon the future we shall have more to say hereafter.

XIV. The history of The Early French School is so closely bound up with that of its Flemish sister, that it is no easy task to separate the two. Indeed, it is sometimes impossible to ascertain whether a Composer, with a French-sounding name, was a true Frenchman, a true Netherlander, or a native of French Flanders. Not only is this the case with the numerous writers whose works are included in the collections published by Pierre Attaignant, Adrian le Roy, and Ballard: but there is a doubt even about the birth of Jean Mouton, who is described by Glareanus as a Frenchman, and by other writers as a Fleming. The doubt, however, involves no critical confusion, since the styles of the two Schools were precisely the same. Both Josquin des Prés and Mouton spent some of the most valuable years of their lives in Paris; and taught their Art to Frenchmen and Netherlanders without distinction. Pierre Carton, Clement Jannequin, Noë Faignient, Eustache du Caurroy, and other Masters of the 16th century, struck out no new line for themselves: while Elziario Genet (Il Carpentrasso), the greatest of all, might easily pass for a born Netherlander. A certain amount of originality was, however, shown by a few clever Composers who attached themselves to the party of the Huguenots, and set the Psalms of Clement Marot and Beza to Music, for the use of the Calvinists, as Walther and his followers had already set Hymns for the Lutherans. The number of these writers was so small, that they cannot lay claim to be classed as a national School; but, few though they were, they carried out their work in a thoroughly artistic spirit. The Psalms of Claudin Lejeune—of which an example will be found in vol. i. p. 762—are no trifles, carelessly thrown off, to serve the purpose of the moment; but finished works of Art, betraying the hand of the Master in every note. Some of the same Psalms were also set by Claude Goudimel, but in a very different style. The Calvinists dolighted in singing their Metrical Psalmody to the simplest Melodies they could find; yet these are veritable Motets, exhibiting so little sympathy with Huguenot custom, that, if it be true, as tradition asserts, that their author perished, at Lyons, on S. Bartholomew's Day, 1572, one is driven to the conclusion that he must have been killed, like many a zealous Catholic, by misadventure. He was one of the greatest Composers the French School ever produced, and excelled by very few in the rest of Europe. Scarcely inferior, in technical skill, to Okenheim and Josquin, he was infinitely their superior in fervour of expression, and depth of feeling. His claim to the honour of having instructed Palestrina has already been discussed elsewhere. Considered in connection with that claim, the following specimen of his style, printed, at Antwerp, by Tylman Susato, in 1554, is especially interesting. [See vol. i. p. 612; vol. ii. p. 635.]

XV. The Roman origin of The Spanish School is so clearly manifest, that it is unnecessary to say more on the subject than has been already said at page 263. After the return of the Papal Court from Avignon, in 1377, Spanish Singers with good Voices were always sure of a warm welcome in Rome; learned Counterpoint, in the Eternal City, first, from the Flemings there domiciled, and afterwards, from the Romans themselves; practised their Art with honour in the Sistine Chapel; and, not unfrequently, carried it back with them to Spain. So completely are the Spaniards identified with the Romans, that the former are necessarily described as disciples of the School of Festa, or that of Palestrina, as the case may be. To the former class belong Bartolomeo Escobedo, Francesco Salinas, Juan Scribano, Cristofano Morales, Francesco Guerrero, and Didaco Ortiz: the greatest genius of the latter was Ludovico da Vittoria, who approached more nearly to Palestrina himself than any other Composer, of any age or country. Many of these great writers including Vittoria ended their days in Spain, after long service in the Churches of Rome: and thus it came to pass that the Roman style of Composition was cultivated, in both countries, with equal zeal, and almost equal success.[14]

XVI. Our rapid sketch of the progress of Polyphony on the Continent will serve materially to simplify a similar account of its development In England, in which country it was practised, as we have already promised to show, at an earlier period than even in the Netherlands.

A hundred years ago, when few attempts had been made to arrange the general History of Music in a systematic form, attention was drawn to the curious 'Rota'—or, as we should now call it, Canon—'Sumer is icumen in,' contained in vol. 978 of the Harleian MSS. Burney estimated the date of this, in rough terms, as probably not much later than the 13th or 14th century. His opinion, however, was a mere guess; while that of Hawkins was so vague that it may safely be dismissed as valueless. Ritson, whose authority cannot be lightly set aside, believed the document—now known as 'The Reading MS.'—to be at least as old as the middle of the 13th century; and accused both Burney, and Hawkins, of having intentionally left the question in doubt, from want of the courage necessary for the expression of a positive opinion. Chappell gives the same date; and complains bitterly of Burney's tergiversation. The late Sir Frederick Madden was of opinion that that portion of the MS. which contains the 'Rota' was written about the year 1240, and has left some notes, to that effect, on the fly-leaf of the volume.[15] Ambros, in the second volume of his 'Geschichte der Musik,' published in 1862, referred the MS. to the middle of the 15th. century, thus making it exactly synchronous with the Second Flemish School. Meanwhile, Coussemaker,[16] aided by new light thrown upon the subject from other sources, arrived at the conclusion that the disputed page could not have been written later than the year 1226; and that the 'Rota' was certainly composed, by a Monk of Reading, some time before that date: and this position he defended so valiantly, that Ambros, most cautious of critics, accepted the new view, without hesitation, in his third volume, printed in 1868.

Assuming this view to be correct, The Early English School was founded a full century and a half before the admission of Dufay to the Pontifical Chapel. But, while giving this discovery its full weight, we must not value it at more than it is worth. It does not absolutely prove that the Art of Composition originated in England. We have already said that the invention of Counterpoint has hitherto eluded all enquiry. It was, in fact, invented nowhere—if we are to use the word 'invention' in the sense in which we should apply it to gunpowder, or the telescope. It was evolved, by slow degrees, from Diaphonia, Discant, and Organum. All we can say about it as yet is, that the oldest known example or, at least, the oldest example to which a date can be assigned with any approach to probability—is English.[17] An earlier record may be discovered, some day; though, thanks to the two-fold spoliation our Ecclesiastical Libraries have suffered within the last 350 years, it is scarcely likely that it will be found in England. Meanwhile, we must content ourselves with the reflection that, so far as our present knowledge goes, the Early English School is the oldest in the world; though the completeness of the Composition upon which this statement is based, proves that Art must have made immense advances before it was written. For, the 'Reading Rota' is no rude attempt at Vocal Harmony. It is a regular Composition, for six Voices; four of which sing a Canon in the Unison, while the remaining two sing another Canon—called 'Pes'—which forms a kind of Ground Bass to the whole. Both Hawkins and Burney have printed the solution in Score. We think it better to present our readers with an accurate fac-simile of the original MS.; leaving them to score it for themselves, in accordance with the directions given in the margin, and to form their own opinion of the evidence afforded by the style of its Caligraphy. In the original copy, the Clefs, Notes, and English words, are written in black; as are also the directions for performance, beginning 'Hanc rotam,' etc. The six Lines of the Stave, the Cross placed to show where the second Voice is to begin, the Latin words, the second initial S, the word Pes, and the directions beginning 'Hoc repetit,' and 'Hoc dicit,' are red. The first initial S is blue, as is also the third. Ambros believes the Latin words, and the directions beginning 'Hanc rotam,' to have been added at a later period, by another hand. Many years have elapsed since our own attention was first directed to the MS., which we have since subjected to many searching examinations. At one period, we ourselves were very much inclined to believe in

the presence of a second hand-writing. But, the evidence afforded by a photograph taken during our investigations convinces us that we did not make sufficient allowance for the different appearance of the black and red letters, which, reduced to the same tone by the process of photography, resemble each other so closely, that we now feel assured that the entire page was written by the same hand. Coussemaker seems to entertain no doubt that this was the hand of John Fornsete, a Reading Monk, of whom we have intelligence in the Cartulary, down to the year 1236, but no other record later than 1226. It seems rash to append this learned Ecclesiastic's name to the 'Rota,' until some farther evidence shall be forthcoming: but it is gratifying to find that the mystery in which the subject has hitherto been shrouded is gradually disappearing.

Besides the above Rota, and a few specimens of unisonous Plain Chaunt, the volume we have described contains three Motets, 'Regina clemencie,' 'Dum Maria credidit,' and 'Ave gloriosa virginum'—at the end of the last of which are three sets of Parts for 'Cantus superius,' and three for 'Cantus inferius,' added in a different hand-writing; and another Motet, 'Ave gloriosa Mater,' written in Three-Part Score, on a Stave consisting of from thirteen to fifteen lines as occasion demands, with a Quadruplum (or fourth Part), added, in different writing, at the end.[18] Beyond these precious reliques, we possess no authentic record of what may be called the First Period of the development of Art in England. Either the School died out, or its archives have perished.

The Second Period, inaugurated during the earlier half of the 15th century, and therefore contemporary with the School of Dufay, is more fully represented, and boasts some lately-discovered reliques of great interest. Its leader was John of Dunstable, a man of no ordinary talent, whose identity has been more than once confused with that of S. Dunstan! though we have authentic records of his death, in 1453, and burial in the Church of S. Stephen, Walbrook, London. In the time of Burney, it was supposed that two fragments only of his works survived; one quoted by Gafurius, the other by Morley. Baini, however, discovered a set of Sæcular Chansons à 3, in the Vatican Library; and a very valuable codex in the Liceo Filarmonico, at Bologna, is now found to contain four of his Compositions for the Church, besides a number of works by other English Composers of the period, most of whom are otherwise unknown.

The Third Period is more bare of records than the First. No trace of its Compositions can be discovered; and the only interest attaching to it arises from the fact that its leaders, John Hamboys, Mus. Doc., Thomas Saintwix, Mus. Doc., and Henry Habengton, Mus. Bac., who all flourished during the reign of King Edward IV. were the first Musicians ever honoured with special Academical Degrees.

The best writer of the Fourth Period was Dr. Fayrfax, who took his Degree in 1511, and is well represented by some Masses, of considerable merit, in the Music School at Oxford, and a collection of Sæcular Songs, in the well-known 'Fayrfax MS.,' which also contains a number of similar works by Syr John Phelyppes, Gilbert Banester, Rowland Davy, William of Newark, and other writers of the School. The style of these pieces is thoroughly Flemish; but wanting, alike in the ingenuity of Okenheim, and the expression of his followers. Still, the School did its work well. England had not fulfilled the promise of her first efforts; but she now made a new beginning, evidently under Flemish instruction, and never afterwards betrayed her trust.

Good work never fails to produce good fruit. If the labours of Fayrfax and Phelyppes brought forth little that was worth preserving on its own account, they at least prepared the way for the more lasting triumphs of the Fifth Period, the Compositions of which will bear comparison with the best contemporaneous productions, either of Flanders, or of Italy. This epoch extends from the beginning of the 16th century, to the period immediately preceding the appearance of Tallis and Byrd; corresponding, in this country, with the dawn of the sera, known in Rome as 'The Golden Age.' It numbered, among its writers, a magnate of no less celebrity than King Henry VIII, who studied Music, diligently, at that period of his life during which it was supposed that he was destined to fill the See of Canterbury, and never afterwards neglected to practise it. No doubt, this early initiation into the mysteries of Art prompted the imperious monarch to extend a more than ordinary amount of encouragement to its votaries, in later life; and to this fortunate circumstance we are probably largely indebted for that general diffusion of the taste for good Music, so quaintly described by Morley, which, taking such firm hold on the hearts of the people that it was considered disgraceful not to be able to take part in a Madrigal, led, ere long, to the final emergence of our School from the trammels of bare mechanical industry into the freedom which true inspiration alone can give. The Composers who took the most prominent part in this great work were John Thorne, John Redford (Organist of Old St. Paul's), George Etheridge, Robert Johnson, John Taverner, Robert Parsons, John Marbeck (Organist of St. George's Chapel, Windsor), Richard Edwardes, and John Shepherde—all men of mark, and enthusiastic lovers of their Art.

Contemporaries of Archadelt and Waelrant, in Flanders, of Willaert, in Venice, and of Festa, in Rome, these men displayed, in their works, an amount of talent in no degree inferior to that shown by the great Continental Masters.

Redford's Anthem, 'Rejoice in the Lord alway,' first printed by Hawkins, and since republished by the Motet Society, is a model of the true Ecclesiastical style, one of the finest specimens of the grand old English School of Cathedral Music we possess. The graceful contour of its Subjects, the purity of the Harmony produced by their mutual involutions, and, above all, the beauty of its expression, entitle it, not only to the first place among the Compositions of its own period, but to a very high one as compared with those of the still more brilliant epoch which was to follow. That the writer of such an Anthem as this should have been an idle man is impossible. He must have produced a host of other treasures. Yet, it is by this alone that he is known to us; and it is much to be feared that he will nevermore be represented by another work of equal magnitude, though it would be well worth while to collect together the few fragments of his writings which are still preserved in MS.[19]

Equally scarce are the works of Richard Edwardes, known chiefly by one of the loveliest Madrigals that ever was written—'In going to my naked bedde.' We have already had occasion to call attention to the beauties of this delightful work,[20] which rivals—we might almost say surpasses—the finest Flemish and Italian Madrigals of the Period, and was certainly never excelled, before the time of Palestrina or Luca Marenzio. For this, also, we have to thank the research and discrimination of Hawkins, who gives it in his fifth volume: but it has since been reprinted, many times; and it is not likely that it will ever again be forgotten.

Johnson was one of the most learned Contrapuntists of the period, and excelled almost all his contemporaries in the art of writing Imitations upon a Canto fermo. Of the writings of Taverner and Parsons, good specimens will be found in the Psalters of Este and Ravenscroft, as well as in the Histories of Burney and Hawkins; while many more remain in MS. Among the latter, a Madrigal for five Voices, by Parsons—'Enforced by love and feare'—preserved in the Library of Christ Church, Oxford, is particularly interesting, as establishing the writer's title to an honourable place among the leaders of a School of Sæcular Music with which his name is not generally associated.

A few of Shepherde's Compositions may be found in a work entitled 'Mornyng and Evenyng Prayer and Communion,' London, 1565. He is also well represented in the Christchurch Library, in a series of MS. Compositions of a very high order of merit. Most of them are Motets, with Latin words; but a few are English Anthems—possibly, adaptations—from one of which we have selected the following example.

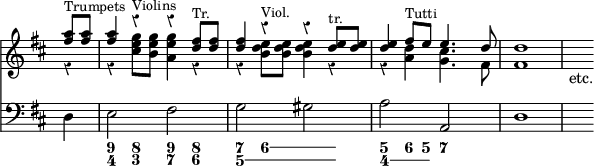

Since the restoration of Anglican Plain Chaunt, by the Rev. T. Helmore, Marbeck's name has been a 'household word' among English Churchmen; but only in connection with his strictly unisonous 'Booke of Common Praier noted.' No one seems to know that he was not only a distinguished Contrapuntist, but also one of the most expressive Composers of the English School. The very few specimens of his style which we possess are of no common order of merit. The example selected is from a MS. Mass, 'Missa, Per anna Justitiæ,' preserved at Oxford, in a set of very incorrectly-written Parts, from which Dr. Burney scored a few extracts. As Marbeck was a zealous follower of the new religion, it is clear that this Mass must have been written during his early life. Where, then, is his English Church Music? It is impossible to believe that so ardent a reformer, and so great a Musician, took no part in the formation of that School of purely English Cathedral Music to which all the best Composers of the period gave so much attention. Surely, some fragments, at least, of his works must remain in our Chapter Libraries.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

The Notes marked *, are sung by the Bass; those marked †, by the Tenor.

We regret that we can find no room for more numerous, or more extended examples, selected from the works of a period which has not received the attention it deserves from English Musicians: but, we trust that we have said and quoted enough to show that this long-neglected School, supported by the learning of Johnson, the flowing periods of Marbeck, and the incomparable expression of Bedford and Edwardes, can hold its own, with honour, against any other of the time; and we are not without hope that our countrymen may some day become alive to the importance of its monuments, and strive to rescue from final oblivion Compositions certainly not unworthy of our regard, as precursors of those which glorified the greatest Period of all—the Period which corresponded with that of the 'Missa Papæ Marcelli' in Italy.

The leader of the Sixth Period was Christopher Tye, whose genius prepared the way, first, for the works of Robert Whyte, and, through these, for those of the two greatest writers who have ever adorned the English School—Thomas Tallis, and William Byrd. Tye's Compositions are very numerous. His best-known work is a Metrical Version of the Acts of the Apostles, in which the simplicity of the Faux-bourdon is combined with a purity of Harmony worthy of the best Flemish Masters, and a spirit all his own. Two of these under other titles—'Sing to the Lord in joyful strains,' and 'Mock not God's Name,' are included in Hullah's 'Part Music,' and well known to Part-singers. Besides these, the Library of Christchurch, Oxford, contains 7 of his Anthems, and 14 Motets, for 3, 4, 5 and 6 Voices; and that of the Music School, a Mass, 'Euge bone,' for 6 Voices, which is, perhaps, the greatest of his surviving works. A portion of the 'Gloria' of this Mass, scored by Dr. Burney, in his second volume, and reprinted in Hullahsa 'Vocal Scores,' will well repay careful scrutiny. One of its Subjects corresponds, very curiously, with a fragment, called 'A Poynt,' by John Shepherde, written, most probably, for the instruction of some advanced pupils, and printed by Hawkins. It is interesting to compare the grace of Shepherde's unpretending though charming little example, with the skilfully constructed network of Imitation with which Tye has surrounded the Subject. We need not transcribe the passages, as they may so easily be found in the works we have named; but, the following less easily accessible example of Tye's broad masculine style will serve still better to exemplify both the quiet power and the melodious grace of his accustomed manner.

Ascendo ad Patrem. Motet à 5.

Still greater, in some respects, than Tye, was Robert Whyte; known only—we shame to say it!—by an Anthem for 5 Voices, 'Lord, who shall dwell in Thy tabernacle?' printed in the third volume of Burney's History, and a few pieces preserved by Barnard; though no less than 35 of his Compositions, comprising 4 Anthems, 25 Motets, and 6 Lamentations, lie in MS. in the Library of Christ Church, Oxford, without hope of publication. These works are models of the best English style, at its best period. Not merely remarkable for their technical perfection, but full of expression and beauty. Yet these fine Compositions have been left to accumulate the dust, while the inspirations of Kent and Jackson have been heard in every Church in England, to say nothing of later Compositions, which would be very much the better for a little infusion of Kent's spontaneity and freshness. In order to give some idea of the tenderness of Whyte's general style, we subjoin an extract from an Anthem—'The Lorde blesse us, and keepe us'—included in Barnard's collection, but neither mentioned in the Christ Church Catalogue, nor noticed by Burney, though it is contained in the valuable and beautifully-transcribed set of Part-Books which furnished him with the text of the only Composition by Whyte that has until now been printed in modern form.[21] The pathetic character of the Hypoæolian Mode was probably never more strongly exhibited than in this beautiful passage.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

The leading Subject is proposed by the Altus of the First Choir, and answered in turn by the Cantus, the Tenor, the Quint us (in this case represented by a Duplicate Altus), and the Bass. The Second Choir enters, after three and a half bars rest, with the same Subject, answered in the same order. The Third Choir enters, one Voice at a time, in the middle of the eleventh bar; the Fourth, at the beginning of the sixteenth bar; the Fifth, at the twenty-third bar; the Sixth, in the middle of the twenty-fourth bar; the Seventh, at the beginning of the twenty-eighth bar; and the Eighth, at the beginning of the thirty-third bar; no two Parts ever making their entry at the same moment. The whole body of Voices is now employed, for some considerable time, in 40 real Parts. A new Subject is then proposed, and treated in like manner. The final climax is formed by a long and highly elaborate passage of 'Quadrigesimal Harmony,' culminating in a Plagal Cadence of gigantic proportions, and concluding with an Organ Point, of moderate length, which we present to our readers, entire. It would be manifestly impossible to write in so many Parts, without taking an infinity of Licences forbidden in ordinary cases. Many long passages are necessarily formed upon the reiterated notes of a single Harmony; and many progressions are introduced, which, even in eight Parts, would be condemned as licentious. Still, the marvel is, that the Parts are all real. Whatever amount of indulgence may be claimed, no two Voices ever 'double' each other. Whether the effect produced be worth the labour expended upon it, or not, the Composition is, at any rate, exactly what it asserts itself to be—a genuine example of Forty-Part Counterpoint: and the few bars we have selected for our example will show this as clearly as a longer extract.[23] (See opposite page.)

As Tallis is chiefly known by his Litany and Responses, so is his great pupil, William Byrd, by 'Non nobis, Domine,' a 'Service,' and a few Anthems, translated from the Latin; while the greater number of his 'Cantiones Sacræ,' his Mass for 5 Voices, and his delightful Madrigals, are recognised only as antiquarian curiosities. The only known copies of his two Masses for 3 and 4 Voices seem, indeed, to be hopelessly lost; nothing having been heard of them, since they were 'knocked down' to Triphook, at the sale of Bartleman's Library, in 1822. But, a goodly number of his works may very easily be obtained, in print; while larger collections of his MS. productions are preserved in more than one of our Collegiate Libraries. We ought to know more of these fine Compositions, the grave dignity of which has never been surpassed. It is in this characteristic that their chief merit lies. They are less expressive, in one sense, than the more tender inspirations of Tallis; but, while they lose in pathos, they gain in majesty. If they sometimes seem lacking in grace, they never fail to impress us by the solidity of their structure, and the grandeur of their massive proportions. Fux makes Three-Part Counterpoint (Tricinium) the test of real power.[24] Was ever more effect produced by three Voices than in the following example, from the 'Songs of Sundrie Natures.' (Lond. 1589.)

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Though Byrd survived the 16th century by more than 20 years, he was not the last great Master who cultivated the true Polyphonic style in England. It was practised, with success, by men who were young when he was old, yet who did not all survive him. We see a very enchanting phase of it, in the few works of Richard Farrant which have been preserved to us. His style is, in every essential particular, Venetian; and so closely resembles that of Giovanni Croce, that one might well imagine the two Masters to have studied together. Farrant is best known by some 'Services,' and three lovely Anthems, the authenticity of one of which—'Lord, for Thy tender mercies' sake'—has lately been questioned, we think on very insufficient grounds, and certainly in defiance of the internal evidence afforded by the character of its Harmonies. Besides these, very few of Farrant's works are known to be in existence. The Organ Part of a Verse-Anthem—'When as we sate in Babylon'—is preserved in the Library at Christ Church; together with two Madrigals, or, rather, one Madrigal in two parts—'Ah! Ah! alas,' and 'You salt sea gods'; but such treasures are exceedingly rare.

Farrant died in 1580, three years before the birth of Orlando Gibbons, with whom the School finished gloriously in 1625. By no Composer was the dignity of English Cathedral Music more nobly maintained than by this true Polyphonist; who adhered to the good old rules, while other writers were striving only to exceed each other in the boldness of their licences. He took licences also. No really great Master was ever afraid of them. Josquin wrote Consecutive Fifths. Palestrina is known to have proceeded from an Imperfect to a Perfect Concord, by Similar Motion, in Two-part Counterpoint. Luca Marenzio has written whole chains of Ligatures, which, if reduced to Plain Counterpoint, in accordance with the stern test demanded by Fux, would produce a dozen Consecutive Fifths in succession. Orlando Gibbons has claimed no less freedom, in these matters, than his predecessors. In the 'Sanctus' of his 'Service in F,' he wrote, between bars 4 and 5, the most deliberate Fifths that ever broke the rule. But he has never degraded the pure Polyphonic style by the admixture of foreign elements incompatible with its inmost essence. He had the good taste to feel what the later Italian Polyphonists never did feel, and never could be made to understand—that the oil of the old system could never, by any possibility, be persuaded to combine with the wine of the new. Of the nauseous mixtures, compounded by Monteverde and the Prince of Venosa, we find no trace, in any one of his writings. Free to choose whichever style he pleased, he attached himself to that of the Old Masters, and conscientiously adhered to it, in spite of the temptations by which he was surrounded on every side. That he fully appreciated all that was good in the newer method is sufficiently proved by his Instrumental Music. His 'Fantasies of III Parts for Viols,' and his Pieces for the Virginals, in 'Parthenia,' are full of quaint fancy, and greatly in advance of the age. But in his Vocal Compositions, he was as true a Polyphonist as Tallis himself. Had he taken the opposite course, he would, no doubt, have been equally successful; for he would, most certainly, have been equally consistent. As it was, he not only did honour to the cause he espoused, but he established an incontestable claim to our regard as one of its brightest ornaments. His exquisitely melodious Anthem, for 4 Voices, 'Almighty and everlasting God,' his 8-part Anthem, 'O clap your hands,' and his magnificent 'Hosanna to the Son of David,' for 6 Voices, are works which would have done honour to the Roman School, in its most brilliant period; and, in purity of intention, and truthfulness of expression, stand almost unrivalled. It is not often that a School ends so nobly: but in England, as in Venice, the last representative of Polyphony was not its weakest champion. No Composer of the period ever wrote anything more worthy of preservation than the too-much-forgotten contents of 'The First Set of Madrigals and Mottets,'[25] from which we have selected the following passage, as strikingly characteristic of the tender pathos with which this great master of expression was wont to temper the breadth of his massive Harmonies, when the sentiment of the words to which they were adapted demanded a more gentle form of treatment than would have been consistent with the sternness of his grander utterances.

It would be manifestly impossible, within the limits of a sketch like the present, to give examples, or even passing notices, of the works of one tenth of the Composers who have adorned the six great Periods of the Early English School. With great reluctance, we must necessarily pass over the names of John Bull, John Mundy, Elway Bevin, Ellis Gibbons, John Hilton, Michael Este, and Adrian Batten; of Douland, Morley, Weelkes, Wilbye, Bennet, Forde, and our noble array of later Madrigal writers; and of many others, too numerous to mention, though much too talented to be forgotten: and we grieve the more to do so, because these men have not been fairly treated, either by their own countrymen or by foreigners. The former have sinned against their School, by neglecting its monuments. The latter, by contemptuously ignoring the subject, without taking the trouble to enquire whether we possess any monuments worth preservation, or not. Time was, when a Venetian Ambassador, writing from the Court of King Henry VIII., could say 'We attended High Mass, which was sung by the Bishop of Durham, with a right noble Choir of Discanters.' And, again, 'The Mass was sung by His Majesty's Choristers, whose Voices are more heavenly than human. They did not chaunt, like men, but gave praise[26] like Angels. I do not believe the grave Bass Voices have their equals anywhere.' If an Italian could thus write of us, in the 16th century, it is clear that we were not always 'an utterly unmusical nation.'[27] And, if we make it possible that such a character should be foisted upon us, now, it can only be, because we have so long lacked the energy to show that we did great things, once, and can—and mean to—do them again. English Musicians are very angry, when foreigners taunt them with want of musical feeling: but, surely, they cannot hope to silence their detractors, while they not only leave the best works of their Old Masters unpublished, and unperformed, but do not even care to cultivate such an acquaintance with them as may at least justify a critical reference to their merits, when the existence of English Art is called in question. We have an early School, of which we need not be ashamed to boast, in presence of those either of Italy, or the Netherlands. If we do not think it worth while to study its productions, we can scarcely expect Italians or Germans to study them for us; nor can we justly complain of German or Italian critics, because, when they hear the inanities too often sung in our most beautiful Cathedrals, they naturally suppose that we have nothing better to set before them. In a later division of our subject, we shall have occasion to speak of wasted opportunities of later date. But we think we have here conclusively proved, that, if our Polyphonic Schools have not obtained due recognition upon the Continent, in modern times, the fault lies, in a great measure, at our own door.[28]

XVII. A long series of progressive triumphs is invariably followed, in the History of Art, by a period of fatal reaction. As a general rule, the seeds of corruption germinate so slowly that their effect is, at first, almost imperceptible. There are, however, exceptions to this law. In the Music Schools of Italy, the inevitable revolution was effected very swiftly. Scarcely had the grave closed over the mortal remains of Palestrina, before the principles upon which he founded his practice were laughed into oblivion by a band of literary savants, themselves incapable of writing an artistic Bass to a Canto fermo.[29] The most eloquent, if not the earliest advocates of 'reform' were, Vincenzo Galilei, and Giovanni Battista Doni: but it was not to them that Polyphony owed its death-blow. The true Founder of The Schools of the Decadence was Claudio Monteverde, in whose Madrigals the rule which forbids the use of Unprepared Discords in Strict Counterpoint was first openly disregarded. In the next division of our subject, we shall have occasion to describe this once celebrated Composer as a genius of the highest order: but we cannot so speak, here, of the ruthless destroyer of a system which, after so many years of earnest striving for perfection, attained it, at last, in the Later Roman School. It was in building up a new School, on a new foundation, that Monteverde showed his greatness, not in his attempts to improve upon the praxis of the Polyphonic Composers. Without good Counterpoint, good Polyphony cannot exist: and his Counterpoint, even before he boldly set its laws at defiance, was so defective, that the conclusion that he discarded it, in despair of ever satisfactorily mastering its difficulties, is inevitable. It is, indeed, much to be regretted that he did not give up the struggle at an earlier period, and devote to the advancement of Monodia the energies, which, when brought to bear upon the work of his immediate predecessors, were productive of nothing but evil: for, however gratefully we may welcome his contributions to the Lyric Drama, we cannot quite so cordially thank him for such attempts to 'rival the harmonies of midnight cats,' as the following passage from his 'Vesperæ,' composed for the Cathedral of S. Mark—a triumph of cacophony which the Prince of Venosa himself might justly have envied.

In one country alone did the Period of the Decadence produce fruit worthy of preservation. Its effect upon Venetian Music is shown in these 'Vesperæ.' In Rome, it formed so serious an hindrance to productive power, that it contributed absolutely nothing to the repertoire of the Pontifical Chapel. But, in England, it gave birth to the Glee, a form of Composition quite distinct from the German Part-Song, and of infinitely higher interest; and of so truly national a character, that it has never, in one single instance, been produced in any other country than our own, or set to other than English words, for which reasons it is doubtful whether full justice could be done to it by any but English Singers. The true relation of the Glee to the older forms of Polyphony will be best understood by comparing the latest English Madrigals with the works of the earliest Glee writers; using the Canzonets of such Composers as Dowland and Ford, as connecting links between the productions of Weelkes, Bateson, and Morley, on the one hand, and those of Battishill, Stevens, and Cooke, on the other. This will show, that, notwithstanding the length of time interposed between the two styles, and the consequent divergence of their tonalities—the use of the Antient Modes having died out with the Madrigal—the newer form could by no possibility have come into existence except upon the ruins of the older one; and it is strange that this last remnant of Polyphony should be found in the country which boasts the earliest specimen of the Art that has as yet been brought to light.

With this beautiful creation, the old régime came absolutely to an end: and it now remains for us to trace the rise and progress of the Monodic Schools.